In 1939, the South African artist Ernest Mancoba turned toward abstraction for the first time. Although this artistic development has been associated with Mancoba’s relationship to the CoBrA movement, Joshua Cohen argues that his embrace of abstraction also can be read as a turn away from the burdens of representation imposed by patrons upon a black South African artist.

To stay alive—psychologically, creatively—the black South African sculptor and painter Ernest Mancoba (1904–2002) managed to leave home.1Even if (self-)exile tends to drive art history in the face of (slow) death, my aim is not necessarily to endorse exile as the “right” option for artists in Mancoba’s position. Some time after Mancoba’s departure, John Koenakeefe Mohl (1903–1985) tried to convince his fellow black South African painter Gerard Sekoto (1913–1993) to stay in the country to stand against racism rather than move to Paris, which Sekoto did in 1947. See Tim Couzens, The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of H. I. E. Dhlomo(Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985), 252. On September 2, 1938, he boarded the SS Balmoral Castle in Cape Town, destined for Southampton, England.2Thos. Cook & Son to Benjamin, Esq., S. A. Institute of Race Relations [SAIRR], June 10, 1938, SAIRR, education, African students overseas, AD843/RJ/Kb3.6, Wits University Historical Papers, Johannesburg. Mancoba’s berth on the steamship, and his concomitant personal and artistic rebirth, resulted from protracted negotiations with liberal patrons who finally agreed to fund a year of study in Paris.3The artist namely negotiated with Senator John David Rheinallt Jones (1884–1953), director of the privately funded South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR), which controlled part of the Bantu Welfare Trust. I am grateful to Anitra Nettleton for clarifying the role and status of the SAIRR. Many South African artists had already traveled to Paris and other European capitals since the nineteenth century,4Lucy Alexander, Emma Bedford, and Evelyn Cohen, Paris and South African Artists, 1850–1965 (Cape Town: South African National Gallery, 1988). but Mancoba was the first black artist to do so. He would not revisit South Africa until after the end of apartheid, and would never live there again.5As a result of leaving the country, Mancoba is not generally considered integral to South African art history.

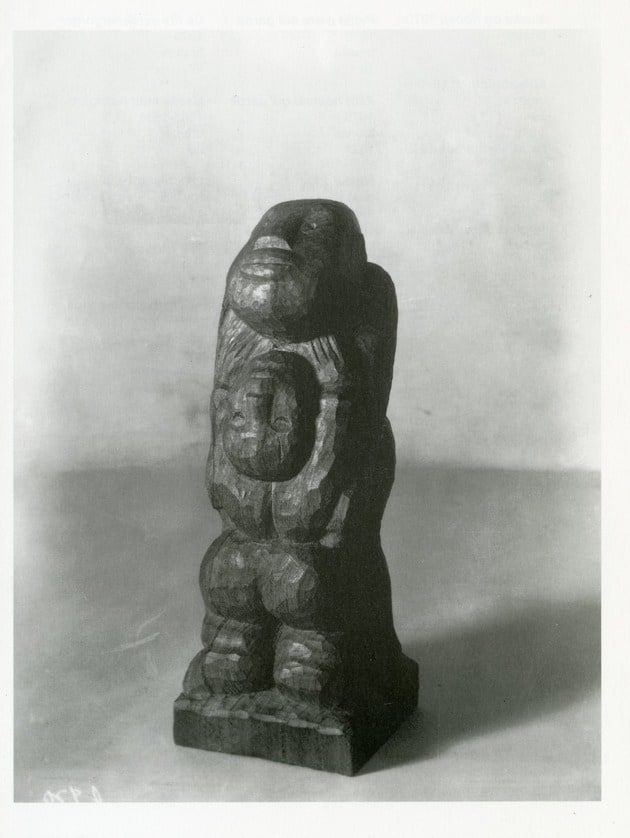

Arriving in Southampton on September 19, Mancoba went directly to London, where he spent a week before continuing on to Paris.6SAIRR correspondence with Major Paul Slessor, August 22, 1938, SAIRR, education, African students overseas, AD843/RJ/Kb3.6, Wits University Historical Papers, Johannesburg. Aside from meeting a few contacts,7Mancoba recalled that in London he saw one Bishop Smythe, a contact from his days at the University of Fort Hare. Mancoba in idem and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest,” in Hans Ulrich Obrist: Interviews, Volume I, ed. Thomas Boutoux (Florence; Milan: Fondazione Pitti Immagine Discovery; Charta, 2003), 564. Margaret Wrong of the International Committee on Christian Literature for Africa wrote that she “spent an evening” with Mancoba in London and was “much impressed by him and his work.” Wrong to J. D. Rheinallt Jones, October 3, 1938, SAIRR, education, African students overseas, AD843/RJ/Kb3.6, Wits University Historical Papers, Johannesburg. Elza Miles notes that Mancoba also tried contacting C. L. R. James (1901–1989), but the Trinidadian journalist and historian was traveling at the time. Miles, Land and Lives: A Story of Early Black Artists (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery; Human and Rousseau, 1997), 139. he made use of his time in London by visiting the African collections at the British Museum. Some two years earlier, Mancoba had first encountered canonical West and Central African sculpture in a library in Cape Town, in the pages of a lavishly illustrated book entitled Primitive Negro Sculpture.8Paul Guillaume and Thomas Munro, Primitive Negro Sculpture (New York: Harcourt, 1926). Guillaume was a leading dealer of African and modern art in Paris. Munro worked for the Barnes Foundation, which funded the publication. Christa Clarke has shown that the Philadelphia-based collector and businessman Albert C. Barnes ghostwrote much of the book. Clarke, “Defining African Art: Primitive Negro Sculpture and the Aesthetic Philosophy of Albert Barnes,” African Arts 36, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 40–51, 92. Despite its unfortunate title, the book’s discovery in Cape Town marked a turning point for the young artist because it catalyzed his embrace of modernism, which to him meant a rough geometric aesthetic modeled on African sculpture.9It was the Cape Town–based modernist Israel “Lippy” Lipshitz (born 1903 Lithuania; died 1980 South Africa) who had urged Mancoba to read Primitive Negro Sculpture. Mancoba in idem and Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest” 562. Mancoba’s iconic first modernist sculpture was called Faith (whereabouts unknown). “Negro Art of Africa. Bantu Sculptors Work. A New Style in Carvings,” The Star(June 8, 1936): 15. Faith is reproduced in Elza Miles, Lifeline out of Africa: The Art of Ernest Mancoba (Cape Town: Human and Rousseau, 1994), 25. Mancoba would see a full African art collection for the first time in London.

To the fortuitous benefit of art history, Mancoba happened to tour the British Museum with an inquisitive writer who published an anonymously bylined article the next month (as “Our Special Representative”) relating the following:

The rest of the story of Ernest Mancoba’s work was told me [sic] in the African room of the British Museum. For a time he was what I can only call passionately absorbed in the primitive art of his people, the carved stools, the figures of fighters, of great tribe-leaders, of women and children. “Look,” he said to me, “they are all serene. Do you know why? My carvings are made to show Africa to the white man. That is why they are sad. These primitive artists were working for the preservation of the group-life. The artists, with the chiefs and priests, are the great leaders of the world. In Africa they carved figures strong and beautiful and free because they wished to lead the people of their tribe to strength, to beauty and to freedom. 10Our Special Representative, “The Sorrow of Africa. An Interview with Ernest Mancoba,” The Church Times (October 28, 1938): 478.

As recounted by the writer, Mancoba remembered his earlier “carvings” as compromised products of the colonial order. Conceived under church and liberal patronage, those sculptures were “sad”; they aimed only “to show Africa to the white man.” The “sad” designation probably did not apply to Mancoba’s recent modernism, but rather to his early production commissioned through the Diocesan Training College at Grace Dieu, an Anglican training college for black schoolteachers in the northern Transvaal Province (now Limpopo), where he had learned wood carving starting around 1925.11For more on the woodcarving program at Grace Dieu, including Mancoba’s training and early career, see especially Elizabeth Morton, “Grace Dieu Mission in South Africa: Defining the Modern Art Workshop in Africa,” in African Art and Agency in the Workshop, eds. Sidney Littlefield Kasfir and Till Förster (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013), 39–64.

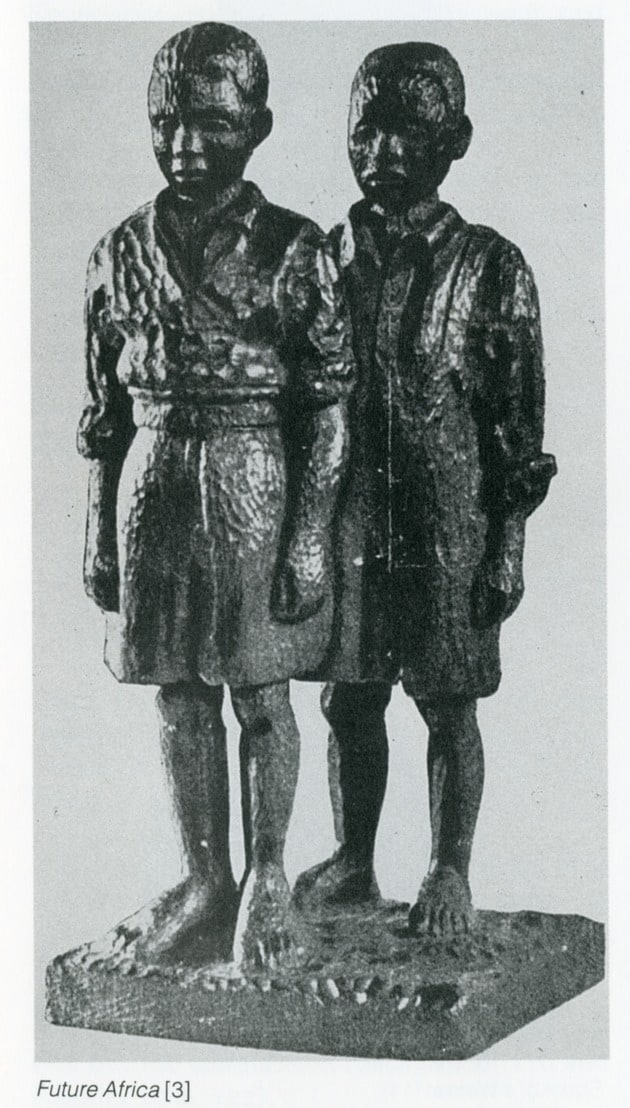

On first glance, Mancoba’s early sculptures do not seem so despairing as he later believed. Future Africa (1934), for example, is ostensibly cheery, figuring two African youths as torchbearers for the continent’s bright future. The sculpture’s reassuring representation of Africans garnered endorsements from liberal critics and patrons.12The work went on view at the South African Academy Exhibition at Selborne Hall in Johannesburg in 1934, and at the May Esther Bedford Bantu Arts Exhibition at Fort Hare in November 1935, where it won an award. “College Notes,” Grace Dieu Bulletin: Magazine of the Diocesan Training College, Pietersburg 2, no. 1 (December 1935): 29. “Exquisite Works in Wood. Sculptor Who Sweeps Floors for a Living. Lives in a Room in District Six,” Cape Times (February 19, 1936): 16. Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 26–27. It is nonetheless pertinent that Future Africabecame “sad” once Mancoba stood appreciating African art in the British Museum in 1938. Quitting South Africa must have yielded a new perspective, and Future Africa betrays desolation upon closer inspection: the boys’ heads are bowed, their eyes downcast, their postures resigned. On a formal level, too, Future Africa arguably undermines its own emancipatory message by failing to break free of colonially imposed academicism.13On the complex and shifting dynamics of naturalism versus stylization as strategies of resistance to colonial rule, see Chika Okeke-Agulu, Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

Mancoba’s contrasting, redemptive reading of African art at the British Museum—“all serene,” “strong and beautiful and free”—suggests a certain penchant for idealism and dreamed-up nostalgia. Still, the artist’s oeuvre would come nowhere close to replicating the romantic “primitivism” of, say, Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) in the South Pacific, or Irma Stern (1894–1966) in Southern Africa.14Born in the Transvaal to German Jewish parents, Stern trained in Germany in the 1910s, notably with the Die Brücke artist Max Pechstein, and came to be strongly influenced by German Expressionism and by the work of Gauguin. Following her move to Cape Town in 1920, she traveled widely in Southern and Central Africa, painting colorful portraits of indigenous “types.” Karel Schoeman, Irma Stern: The Early Years, 1894–1933 (Cape Town: South African Library, 1994), 44–64. Marilyn Wyman, “Irma Stern: Envisioning the ‘Exotic,’” Woman’s Art Journal 20, no. 2 (Autumn–Winter 1999): 18–23, 35. Anitra Nettleton, “Primitivism in South African Art,” in Visual Century: South African Art in Context, vol. 2, 1945–1976, ed. Lize van Robbroeck (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2011), 143–45. Soon after arriving in Paris on September 27, Mancoba began attending classes at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs, where he befriended several artists associated with the Danish Abstract Surrealist group Linien: Christian Poulsen (1911–1991), Ejler Bille (1910–2004), and Sonja Ferlov (1911–1984).15Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 33. Mancoba in idem and Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest” 565. On Linien (The Line; 1934–39), see Jean-Clarence Lambert, Cobra, trans. Roberta Bailey (New York: Abbeville Press, 1983), 29–31; Eleanor Flomenhaft, The Roots and Development of Cobra Art (Hempstead, NY: Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, 1985), 21–23; Willemijn Stokvis, Cobra: The Last Avant-garde Movement of the Twentieth Century (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2004), 123–24; and Kerry Greaves, “Mobilizing the Collective: Helhesten and the Danish Avant-Garde, 1934–1946” (PhD diss., The City University of New York, 2015), 30–81. Communicating in English, Mancoba and the Danes shared an outsider status in Paris, as well as common interests in modernism and African sculpture.

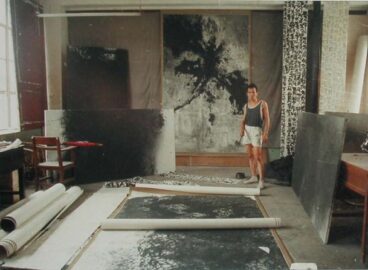

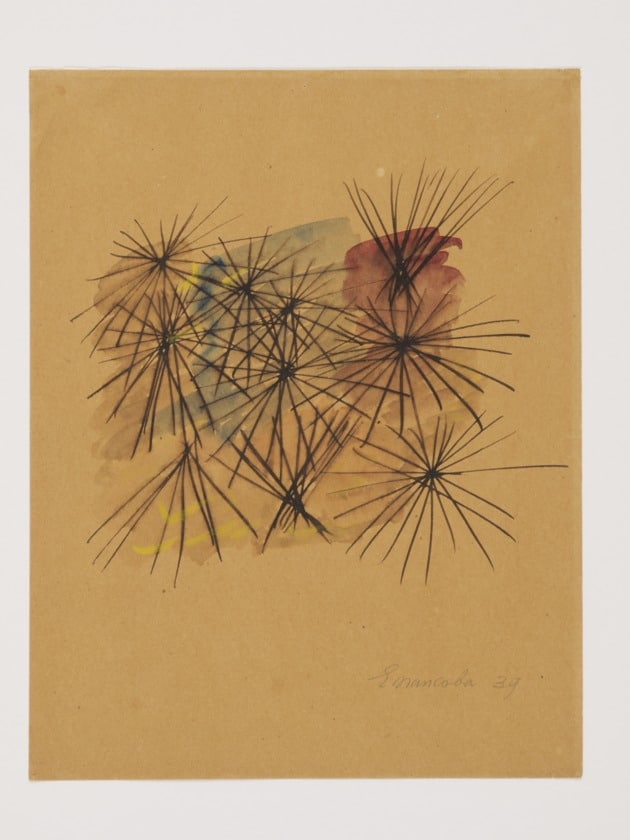

Although canonical African sculpture had initially informed Mancoba’s modernism, and would inform it subsequently, his practice took a different turn in 1939 after his experience in London and at the start of his relationship with the Danes. Not only did he stop making three-dimensional work, but he also jettisoned any ambition toward representation. To cease production of “sad” images, the artist fully—if momentarily—embraced abstraction. Two surviving watercolors from this period adopt an elementary visual grammar: straight lines and pure color. In one composition, pale swaths of blue, red, and orange-brown make up a shallow plane overlaid with black rosettes. The other composition suggests a spherical space, with crosshatched grids permeating a cloud of soft hues. Given the artist’s particular trajectory, his abstractions hint at something personal and political mapped onto a new formal horizon. Abstraction, for Mancoba, meant turning his back on South African patrons’ demands for sanguine images of “native” life.

Instantiating those demands—and setting the stage for the abstract turn—was a job offer Mancoba received from the South African government’s Department of Native Affairs in the spring of 1936.16“Native Sculptor’s Ambition Realised,” Rand Daily Mail (March 14, 1936): 12. “Native Sculptor to Get His Chance. Under Friendly Eye of Government,” Cape Times (March 17, 1936): 5. “African Sculptor Given a Chance. Department of Native Affairs Give Mancoba Employment,” Bantu World (April 16, 1936), 20. “Did You Know That . . .?” Grace Dieu Bulletin: Magazine of the Diocesan Training College, Pietersburg 2, no. 2 (June 1936): 25. Dr. N. J. van Warmelo, a Native Affairs ethnologist, hoped to hire Mancoba to craft saleable souvenirs for the Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg, scheduled for that fall.17Mancoba in idem and Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest” 563. Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 13–14. Echoing Warmelo’s aims, press coverage from this period reinforced common colonialist conceptions of black artists as instinct-driven traditionalists and representatives of their “race.”18“Native Sculptor’s Ambition Realised,” Rand Daily Mail (March 14, 1936): 12. “Native Sculptor to Get His Chance. Under Friendly Eye of Government,” Cape Times (March 17, 1936): 5. On assumptions about “self-taught” black South African artists during roughly the same period, see Daniel Magaziner, The Art of Life in South Africa(Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2016), 25–51. Mancoba initially accepted the offer, which carried a certain privilege and would guarantee steady work. But he subsequently reconsidered the position and refused it, pivoting instead toward Paris.19Given the press reports announcing that Mancoba would take the job, it seems likely that he first tentatively accepted the offer or at least engaged in negotiations. In a film interview, Mancoba recounted the episode as follows: “When the work I was trying to do in Cape Town with my sculpture came into the notice of the Native Affairs Department, the Commissioner in Pretoria of Native Affairs wrote and asked if I was willing to go over to Pretoria where they could give me space and a room where I could make little oxen . . . ox things and cows for tourists. But I was completely flabbergasted. I couldn’t take it. I knew it was beautiful and all that kind of thing but I couldn’t take it. I had a vision of the work which was done by people like van Gogh and other artists who were looking forward to a new approach of art in the world.” Mancoba in Ernest Mancoba at Home, dir. Bridget Thompson (Woodstock, South Africa: Tómas Films, 2000).

Mancoba’s challenge to art history partly involves learning to interpret his circa 1939 abstraction—and “black” abstraction more broadly. Whereas Euro-American art genealogies tend to be discussed in terms of ideas and imagination, tout court, art from outside that realm still often gets pegged to artists’ identities, and framed as the product of experiences marked as “other.” Some black artists historically have responded to such formulas by seeking to evade them, notably by way of abstraction. In noting that Mancoba’s 1939 watercolors anticipated abstract art among African-descended modernists elsewhere, the lesson is not one of establishing precedence but rather of seeing parallels across contexts—including a perennial insistence on pigeonholing artists of color, irrespective of the nature of their work. Wherever the artist seeks to escape compartmentalization, the critic or scholar works at cross-purposes by qualifying his/her abstraction as “African” or “black.”

Art historian Darby English, researching the painter Ed Clark (born 1926) and other postwar African-American abstractionists, has found “the urge for symmetry between biography and picture-effects [to be] so strong in black art history that the turbulent color work in the art is impotent next to the sureness that it, or something in the picture, reflects back all the unassailable epistemological stability of [. . .] racial blackness.”20Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 68; italics in original. I have omitted Clark’s name from the end of this statement, which I take to encapsulate English’s broader aims. But I do not wish to leave out Clark, who is also important to African modern art history: the Senegalese painter Souleymane Keita (1947–2013) cited Clark as a friend and major influence during his time in New York in the 1980s. See Joshua I. Cohen, “Souleymane Keita: Traversées,” in Actes du colloque: Avant que la “magie” n’opère: Modernités artistiques en Afrique, eds. Maureen Murphy and Nora Gréani (Paris: Institut National de l’Histoire de l’Art; Histoire Culturelle et Sociale de l’Art, Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2017). See also the excellent essay on Mancoba in the same conference proceedings by Sarah Ligner, “Ernest Mancoba, un artiste modern africain?” Surveying the South African context, historian Daniel Magaziner has similarly charged that art history may “share with the apartheid state the conviction that as black artists, individual creators approached their canvas, wood, or stone with a set of predictable concerns born of their supposed racial identity—to be political or not, to be ‘modern’ or ‘traditional.’ Who they were thought to be determines how we understand their work.”21Magaziner, The Art of Life, 12–13. These statements, and the important recent studies from which they are drawn, grapple with complications and difficulties involved in reconciling “black” and “art.” Racial and political dimensions to art-making cannot be expunged with the will to abstraction. But neither can they be taken as all determining. As Mancoba’s work reveals, abstraction could itself be a form of retaliation against racialist orthodoxies, executed with freedom in mind. Such moves are nuanced and complex even as they relate back to a basic question: how might it look to be simply human, yet extraordinarily alive?

In the event, Mancoba’s signature style required one more decisive move. Rather than stay with nonobjective painting, the artist reintegrated the human form in a radically new configuration devised by appropriating figural and design elements from the African canon.22It should be noted that Linien artists also tended to steer clear of complete abstraction and made use of the trope of the mask. Mancoba’s Composition (1940)—his first effort in this vein and his first-ever painting on canvas—imaginatively “modernizes” a Congolese Kuba mask (as art historian Elza Miles has convincingly proposed)23Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 39. by integrating flat chevrons, geometric shapes, and grids. Did Mancoba stray from nonobjectivity for the reason that hypothetically, once emptied of all signs of identity, his art could appear to have been made by anyone? Since authors of abstract art around this time were presumptively European descended, the resultant confusion would hardly suit an African modernist intent on overturning assimilationist doctrines underpinning imperial “civilizing missions.” For Mancoba and others of his generation, complete abstraction carried a danger of signaling alienation, in the sense of posing or passing as something foreign. Perhaps to preempt any such misreading while retaining key lessons from abstraction, Mancoba reintroduced elements from African material culture and abstracted them, resulting in a deep amalgamation of indigenous African and modernist European formal aesthetics. This tactic would continue to animate Mancoba’s production in the decades to come.

- 1Even if (self-)exile tends to drive art history in the face of (slow) death, my aim is not necessarily to endorse exile as the “right” option for artists in Mancoba’s position. Some time after Mancoba’s departure, John Koenakeefe Mohl (1903–1985) tried to convince his fellow black South African painter Gerard Sekoto (1913–1993) to stay in the country to stand against racism rather than move to Paris, which Sekoto did in 1947. See Tim Couzens, The New African: A Study of the Life and Work of H. I. E. Dhlomo(Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985), 252.

- 2Thos. Cook & Son to Benjamin, Esq., S. A. Institute of Race Relations [SAIRR], June 10, 1938, SAIRR, education, African students overseas, AD843/RJ/Kb3.6, Wits University Historical Papers, Johannesburg.

- 3The artist namely negotiated with Senator John David Rheinallt Jones (1884–1953), director of the privately funded South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR), which controlled part of the Bantu Welfare Trust. I am grateful to Anitra Nettleton for clarifying the role and status of the SAIRR.

- 4Lucy Alexander, Emma Bedford, and Evelyn Cohen, Paris and South African Artists, 1850–1965 (Cape Town: South African National Gallery, 1988).

- 5As a result of leaving the country, Mancoba is not generally considered integral to South African art history.

- 6SAIRR correspondence with Major Paul Slessor, August 22, 1938, SAIRR, education, African students overseas, AD843/RJ/Kb3.6, Wits University Historical Papers, Johannesburg.

- 7Mancoba recalled that in London he saw one Bishop Smythe, a contact from his days at the University of Fort Hare. Mancoba in idem and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest,” in Hans Ulrich Obrist: Interviews, Volume I, ed. Thomas Boutoux (Florence; Milan: Fondazione Pitti Immagine Discovery; Charta, 2003), 564. Margaret Wrong of the International Committee on Christian Literature for Africa wrote that she “spent an evening” with Mancoba in London and was “much impressed by him and his work.” Wrong to J. D. Rheinallt Jones, October 3, 1938, SAIRR, education, African students overseas, AD843/RJ/Kb3.6, Wits University Historical Papers, Johannesburg. Elza Miles notes that Mancoba also tried contacting C. L. R. James (1901–1989), but the Trinidadian journalist and historian was traveling at the time. Miles, Land and Lives: A Story of Early Black Artists (Johannesburg: Johannesburg Art Gallery; Human and Rousseau, 1997), 139.

- 8Paul Guillaume and Thomas Munro, Primitive Negro Sculpture (New York: Harcourt, 1926). Guillaume was a leading dealer of African and modern art in Paris. Munro worked for the Barnes Foundation, which funded the publication. Christa Clarke has shown that the Philadelphia-based collector and businessman Albert C. Barnes ghostwrote much of the book. Clarke, “Defining African Art: Primitive Negro Sculpture and the Aesthetic Philosophy of Albert Barnes,” African Arts 36, no. 1 (Spring 2003): 40–51, 92.

- 9It was the Cape Town–based modernist Israel “Lippy” Lipshitz (born 1903 Lithuania; died 1980 South Africa) who had urged Mancoba to read Primitive Negro Sculpture. Mancoba in idem and Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest” 562. Mancoba’s iconic first modernist sculpture was called Faith (whereabouts unknown). “Negro Art of Africa. Bantu Sculptors Work. A New Style in Carvings,” The Star(June 8, 1936): 15. Faith is reproduced in Elza Miles, Lifeline out of Africa: The Art of Ernest Mancoba (Cape Town: Human and Rousseau, 1994), 25.

- 10Our Special Representative, “The Sorrow of Africa. An Interview with Ernest Mancoba,” The Church Times (October 28, 1938): 478.

- 11For more on the woodcarving program at Grace Dieu, including Mancoba’s training and early career, see especially Elizabeth Morton, “Grace Dieu Mission in South Africa: Defining the Modern Art Workshop in Africa,” in African Art and Agency in the Workshop, eds. Sidney Littlefield Kasfir and Till Förster (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013), 39–64.

- 12The work went on view at the South African Academy Exhibition at Selborne Hall in Johannesburg in 1934, and at the May Esther Bedford Bantu Arts Exhibition at Fort Hare in November 1935, where it won an award. “College Notes,” Grace Dieu Bulletin: Magazine of the Diocesan Training College, Pietersburg 2, no. 1 (December 1935): 29. “Exquisite Works in Wood. Sculptor Who Sweeps Floors for a Living. Lives in a Room in District Six,” Cape Times (February 19, 1936): 16. Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 26–27.

- 13On the complex and shifting dynamics of naturalism versus stylization as strategies of resistance to colonial rule, see Chika Okeke-Agulu, Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

- 14Born in the Transvaal to German Jewish parents, Stern trained in Germany in the 1910s, notably with the Die Brücke artist Max Pechstein, and came to be strongly influenced by German Expressionism and by the work of Gauguin. Following her move to Cape Town in 1920, she traveled widely in Southern and Central Africa, painting colorful portraits of indigenous “types.” Karel Schoeman, Irma Stern: The Early Years, 1894–1933 (Cape Town: South African Library, 1994), 44–64. Marilyn Wyman, “Irma Stern: Envisioning the ‘Exotic,’” Woman’s Art Journal 20, no. 2 (Autumn–Winter 1999): 18–23, 35. Anitra Nettleton, “Primitivism in South African Art,” in Visual Century: South African Art in Context, vol. 2, 1945–1976, ed. Lize van Robbroeck (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2011), 143–45.

- 15Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 33. Mancoba in idem and Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest” 565. On Linien (The Line; 1934–39), see Jean-Clarence Lambert, Cobra, trans. Roberta Bailey (New York: Abbeville Press, 1983), 29–31; Eleanor Flomenhaft, The Roots and Development of Cobra Art (Hempstead, NY: Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, 1985), 21–23; Willemijn Stokvis, Cobra: The Last Avant-garde Movement of the Twentieth Century (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2004), 123–24; and Kerry Greaves, “Mobilizing the Collective: Helhesten and the Danish Avant-Garde, 1934–1946” (PhD diss., The City University of New York, 2015), 30–81.

- 16“Native Sculptor’s Ambition Realised,” Rand Daily Mail (March 14, 1936): 12. “Native Sculptor to Get His Chance. Under Friendly Eye of Government,” Cape Times (March 17, 1936): 5. “African Sculptor Given a Chance. Department of Native Affairs Give Mancoba Employment,” Bantu World (April 16, 1936), 20. “Did You Know That . . .?” Grace Dieu Bulletin: Magazine of the Diocesan Training College, Pietersburg 2, no. 2 (June 1936): 25.

- 17Mancoba in idem and Obrist, “Mancoba, Ernest” 563. Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 13–14.

- 18“Native Sculptor’s Ambition Realised,” Rand Daily Mail (March 14, 1936): 12. “Native Sculptor to Get His Chance. Under Friendly Eye of Government,” Cape Times (March 17, 1936): 5. On assumptions about “self-taught” black South African artists during roughly the same period, see Daniel Magaziner, The Art of Life in South Africa(Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2016), 25–51.

- 19Given the press reports announcing that Mancoba would take the job, it seems likely that he first tentatively accepted the offer or at least engaged in negotiations. In a film interview, Mancoba recounted the episode as follows: “When the work I was trying to do in Cape Town with my sculpture came into the notice of the Native Affairs Department, the Commissioner in Pretoria of Native Affairs wrote and asked if I was willing to go over to Pretoria where they could give me space and a room where I could make little oxen . . . ox things and cows for tourists. But I was completely flabbergasted. I couldn’t take it. I knew it was beautiful and all that kind of thing but I couldn’t take it. I had a vision of the work which was done by people like van Gogh and other artists who were looking forward to a new approach of art in the world.” Mancoba in Ernest Mancoba at Home, dir. Bridget Thompson (Woodstock, South Africa: Tómas Films, 2000).

- 20Darby English, 1971: A Year in the Life of Color (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 68; italics in original. I have omitted Clark’s name from the end of this statement, which I take to encapsulate English’s broader aims. But I do not wish to leave out Clark, who is also important to African modern art history: the Senegalese painter Souleymane Keita (1947–2013) cited Clark as a friend and major influence during his time in New York in the 1980s. See Joshua I. Cohen, “Souleymane Keita: Traversées,” in Actes du colloque: Avant que la “magie” n’opère: Modernités artistiques en Afrique, eds. Maureen Murphy and Nora Gréani (Paris: Institut National de l’Histoire de l’Art; Histoire Culturelle et Sociale de l’Art, Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 2017). See also the excellent essay on Mancoba in the same conference proceedings by Sarah Ligner, “Ernest Mancoba, un artiste modern africain?”

- 21Magaziner, The Art of Life, 12–13.

- 22It should be noted that Linien artists also tended to steer clear of complete abstraction and made use of the trope of the mask.

- 23Miles, Lifeline out of Africa, 39.