Chen Zhen’s death in 2000 did not stop his art from living on, thanks to the hard work of Xu Min—Chen Zhen’s widow, who continues to organize his solo shows and also to restore his artworks. Xu was trained as an artist in Shanghai, but she has dedicated herself to supporting Chen’s art since the couple reunited in Paris in 1989, three years after Chen moved there. Chen, a diligent thinker, lived for only forty-five years. Though he left an abundant body of work and many interviews related to it, his life story, especially how he turned from painting to more a conceptual practice, and how this process related to his illness, has remained a mystery. In this interview, Xu Min speaks from her perspective as Chen’s life partner, assistant, and conservator; she discusses his life and career—from his early art training, his sudden illness, and his subsequent move from Shanghai to Paris to his philosophy toward work, life, death, disease, and the human condition. Though Chen succumbed to death, his multifaceted art remains vital.

Paris, June 24, 2014. Translation by Lina Dann. Edited by Yu-Chieh Li.

How did you and Chen Zhen meet? What was your early art training in Shanghai like?

I met Chen Zhen when I was seventeen and he was eighteen. Both of us had been studying painting long before that; Chen Yifei was my sketch teacher and Chen Zhen studied with Yen Guoji [a portrait artist at the Shanghai Chinese Painting Institute]. At the time my father and Chen Zhen’s parents all worked at Ruijin Hospital in Shanghai; one day, his parents brought him to Chen Yifei’s class, and that was the beginning of our relationship. My uncle was the director of the Oil Painting and Sculpture Studio at the Shanghai Chinese Painting Institute. He had introduced me to the studio, and I was well acquainted with the people there. However, at that time, I wasn’t interested in drawing and painting; I was all about dancing—I even auditioned for the Shanghai Opera. My uncle was concerned. He told me that dancers have brief careers, that most of them retire early—in their twenties or thirties. He persuaded me that visual artists, on the other hand, mature as they grow older, benefiting from the experience accumulated with aging. Therefore, I gave art a shot, starting with sculpture and then shifting to painting. My first-ever sculpture lesson was with Zhang Chongren.

Soon after, Chen Zhen was admitted to the Shanghai School of Arts and Crafts. He boarded there and came home on weekends. He would often drop by my house and tell me fascinating tales about school. He convinced me to apply as soon as I graduated, which I did. And, just like that, we became schoolmates. At school, we pretended not to know each other, and for three whole years, we had everyone fooled. He majored in ivory carving, while I chose jade carving. I might have chosen ivory if it had been offered in my year, but it wasn’t, and so I chose jade.

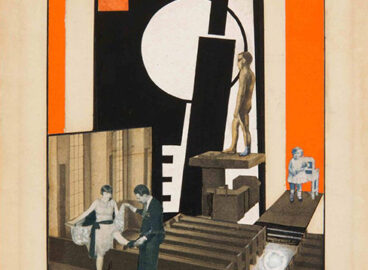

By that time, Chen Zhen had already mastered sketching. At school, he was close to Yu Youhan, a teacher whom he admired for his personality and the way he understood and applied colors. Upon graduation, he wished to continue studying, and so he did a postgraduate degree program, which took another four years, and he majored in stage design through the drama department at the Shanghai Theatre Academy. He learned many oil painting techniques there from Professor Chen Junde, and he developed a better, more systematic understanding of space.

When was Chen Zhen diagnosed with his disease, and how did he end up going abroad?

Chen Zhen got sick the year he graduated from Shanghai Theatre Academy. It was a sudden attack. Now that I think about it, he never was a detail-oriented person, and he would overlook subtle signs or warnings from his body. He would do things like ride a bike in the rain to go sketching from nature and then come home having spiked a fever. At times he would stay up late working and then fall asleep in his clothes. As a result, he was often troubled by colds and flus, and would self-medicate with sulfonamide drugs. When he was twenty-five, a drug allergy caused him to have an endocrine disorder, and he was diagnosed with hemolytic anemia. His limbs went limp and he struggled for breath when he climbed the stairs. His brother and sister-in-law were both hematologists, and they could tell right away that there was something very wrong with him. They urged him to get examined at a hospital, which he did, and hemolytic anemia was the diagnosis—a disease that is hard to target and cure. The doctors told Chen Zhen’s parents that he might have only five years to live.

From where I stand, I can say that Chen Zhen was an extraordinary man with great perseverance. His mind never stopped working, and so even when he was lying sick in bed, he still accomplished a great many things. He used to be physically fit, a proud young man who was a good swimmer, who played center forward for his basketball team. He was alive and active in school. He served as the chairman of the student council and later became a teacher. Yet this disease really brought him down. The many rounds of hormonal treatments took a physical toll, and he grew less handsome. But personally, I preferred Chen Zhen in his later years, because his mind and will were stronger than ever and his personality was much more mature and stable. After eleven years of dating, we finally got married. He was hospitalized while I was pregnant, and we had rooms on opposite ends of the same hospital. When our child was born, he came by my ward to visit, and we were both wearing hospital gowns.

Chen Zhen left the country in 1986. It was a winter—six months after our son was born. I had a hard time understanding how his parents could let their son—a patient—travel so far away and alone! At the time, his brother and sister-in-law were doing their PhDs in Paris. His brother thought about how his younger brother might have only five more years to live, and how he wished he would have a chance to at least take a look at the rest of the world, and especially at European art and the original artworks in the Louvre. He knew that Chen Zhen had read about them in catalogues—and that the catalogues were all worn out. So Chen Zhen’s brother applied to the Paris art academies for him. Chen Zhen was over thirty years old, and it was tough finding a school that would take him. Luckily, there were teachers at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts who didn’t mind having older students—and Mr. Bingas was one of them. He admired Chen Zhen’s oil painting technique and accepted his application to study color theory. Bingas recognized Chen Zhen’s skills in oil painting. He knew that for the Chinese students, the purpose of studying abroad is not necessarily to attend lectures; a lot of times, these students yearned for a legitimate reason to extend their visas. So after a while, Mr. Bingas told Chen Zhen that he was only required to go to the studio twice a week, and he also offered to teach him French. Chen Zhen used his spare time to visit galleries in Paris, to immerse himself in the artistic atmosphere and gather as much information as possible on local modern art, which was definitely easier said than done, for he had no clue how to proceed. Huang Yong Ping, who would later become his friend, hadn’t yet come to Paris, and Chen Zhen hadn’t met Yan Pei-Ming yet either; the only contacts he had at the time were a few Chinese friends who were working as street painters.

It is said that the grass is always greener on somebody else’s land, which to me, was Paris. I thought it must be paradise there! The weather in Paris suited Chen Zhen. His body wasn’t made to endure the hot, humid climate of Shanghai. When we were students, we had to fight the summer by staying inside from sunup to sundown, studying in the air-conditioned library. Knowing that Chen Zhen would do so much better in the mild climate in France was a comfort to me.

At the time, I was working as a teacher at the Shanghai School of Arts and Crafts, and I also was taking classes in bird-and-flower painting and traditional Chinese design patterns. I stayed in China with our son, and we were separated from Chen Zhen for three years. We didn’t communicate much. Phone calls were a luxury, costing 100 RMB for three minutes; at the time, I was making 36 RMB a month as a teacher, and so that meant a short phone call cost three months’ salary. Every time we talked, it had to be short and the ending was always abrupt; it was so distressing, almost too much to bear, and often it felt worse than not calling at all. At the beginning, I had no idea Chen Zhen was living a tough life in Paris. When our son was two, I wrote Chen Zhen a letter. I told him, “Our son is almost two years old. I have been showing him pictures of you and he keeps uttering ‘Daddy.’ Could you come home, even if it is only for a short while? It’s okay if you want to return to Paris, but then at least our son will have had a chance to know you and connect with you.” Upon reading my letter, Chen Zhen decided to come home for a visit, but he didn’t have much money to spare; he had to spend all he had on the plane ticket.

When he came home, he brought us a box of chocolates and a small wooden toy. He couldn’t stay long in Shanghai because of his visa issues. One night, when our son was asleep in his little bed, I walked out of the shower and into the room, and for the first and last time in my life, I saw Chen Zhen crying. Chen Zhen had never shed a tear during his sickness and he was strong until the very end of his life. But that night, he cried very hard. I asked him what was wrong and said, “You should tell me everything.” He said, “Xu Min, I don’t know when I will be able to reunite with you. I can’t see it coming. The future is so grim.” I said, “But isn’t life in Paris great? Your brother and sister-in-law are there, too.” He said, “No, Xu Min, it’s not how you think it is. It’s not like I’ve struck gold there; things are difficult, and I don’t know when I will be able to bring you both to Paris.” So I said, “Chen Zhen, if this is the case, then I should go with you. Two is always better than one.” To this he said, “But it’s so comfortable here at home. You have a maid to help you with everything. Over there, you would have nothing and nobody!” I said, “If that is the case, all the more reason I should go with you.” He agreed. I waited a whole year for the visa. In 1989 I was finally reunited with Chen Zhen in Paris, but I had to leave our three-year-old son in China. We weren’t able to see him until he was four, when Chen Zhen’s parents took a chance by bringing him over en route to an international endocrine conference.

After I came to Paris in 1989, we started street painting, trying to save up some money. Each morning we would go to the Plaza Pompidou; we’d spend afternoons at the Eiffel Tower plaza, and finally end up at night at the Champs-Élysées. Our customers were the wealthy—oil tycoons and rich Arabs. They would exit the theater at around twelve or one o’clock and ask us—almost jokingly—to draw them. They didn’t even glance at the paintings when we were done; they just paid up, sometimes double, and left. I remember the first time I ever did a street drawing. I never got paid for it. When the lady was about to hand me the money, the police came by and stopped her. I ended up giving her the drawing. “Since it is you I drew, you should keep it,” I said. She almost burst into tears. Not only did I not make any money, Chen Zhen and I ended up at the police station. We were released later that night, after the subway had closed, and so we had to spend a fortune on a cab to our faraway home. We were living in a single room in a seventh-floor walkup; it couldn’t have been bigger than 90 square feet. When we got home, we were so exhausted we could barely make it up the stairs.

How did Chen Zhen start working on installations?

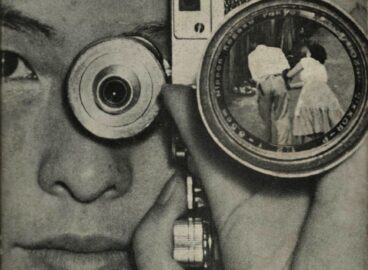

When Chen Zhen first came to Paris, he took part in a few group exhibitions. Sometimes they were exhibitions of work by Chinese artists, and those shows featured small-size paintings. After 1986 he did some other group exhibitions of the work of young artists, which is when he met Jerôme Sans. At first Jerôme was interested in Chen Zhen’s personality, and when he asked Chen Zhen what he did for a living, Chen Zhen said he was a reporter. This is because Chen Zhen was studying art all alone, and he felt that claiming to be a reporter would get him more and better opportunities to socialize, because it would be easier to keep a conversation going. He drew a lot of sketches, and little by little, he went from working on the wall to working within three-dimensional space; he went from paintings to installations. He was a very upbeat, optimistic person. When he was by himself in Paris, he did whatever he felt like doing. It was a fairly precious time; he had absolute control of his time, which he used feverishly to learn French and do all kinds of analytical and academic work on Parisian art exhibitions. The day I arrived in Paris—in February 1989—I realized that his fridge was completely empty and that we had nothing to eat. I had to go to the grocery store and buy food before we could sit down and have a meal. Chen Zhen, on the other hand, was more eager to show me all the sketches he had done in the past three years. He showed me—excitedly—the notes that he had written down whenever he could. Those notes started in Chinese, progressed to some French scribbling on the side, and then gradually were all in French. A while later, our life in Paris consisted of going out to do street paintings. Around this same time Chen Zhen revisited his handwritten notes. We hoped to put together some money to buy tools so we could make some installation pieces. By the end of 1989 we had accumulated around 2000 francs, and so we leased a shabby little house in District 20 and made it our studio. We even had to install the door ourselves. We bought an electric welder and some very basic tools, and we made Chen Zhen’s very first installation piece.

As Chen Zhen’s partner and assistant, do you see yourself as a second author?

The later part of my life was spent working on Chen Zhen’s artworks. When we worked together, it was always harmonious and joyful, which is why after he was gone, a large part of my grief had to do with the loss of this happy part of our relationship. Every artwork’s creation was like the birth of a new baby. I was aware that the works were the presentation of Chen Zhen’s ideas; I helped him realize those concepts while aiding in resolving technical difficulties. Because we were so in sync, I could always understand what he had to say or wanted to present. We rarely ever fought over work.

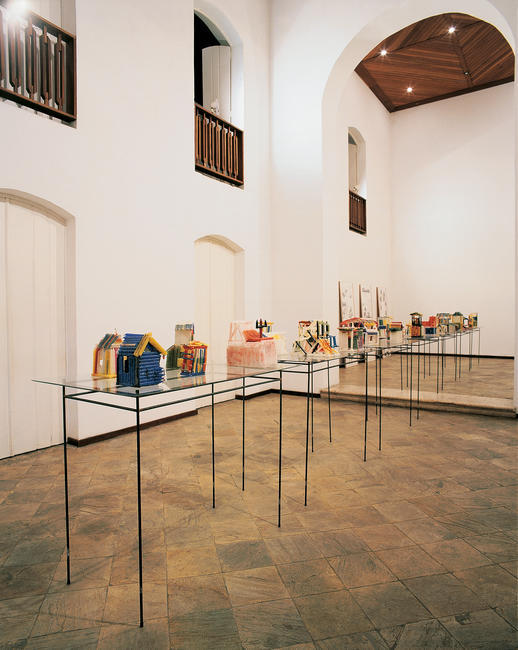

The first piece we did with candles—Beyond the Vulnerability (1999)—was done in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. France Morin, the curator, had artists work together with a local children’s foundation to create artworks. The children there were underprivileged, living in poor conditions; more often than not, their houses consisted of nothing more than a few pieces of cardboard thrown together, or anything that would keep out the rain. Chen Zhen wanted these kids to be able to build the houses of their dreams, and so he searched and searched for the right materials for them to work with.

One day when Chen Zhen was walking down the street, he saw some beautiful candles and sticks of wood; they were so beautiful that he instantly decided to use them. Now how do you make candles stick together? He came up with the idea of using the heat from an electric cautery to melt the sides of the candles so that they could be stuck together. After that, he did his second piece with candles and chairs—A Village Without Borders (2000).

This series consists of ninety-nine little candle houses. To Chen Zhen, the number “99” represented “infinity”; “100,” on the other hand, implied “a stopping point.” This was a village without borders, and his dream was to have all ninety-nine houses exhibited together. This piece has traveled worldwide, and each house is in the hands of a different collector, and so in a sense, it really has become “a village without borders.” However, it would be logistically challenging to exhibit all of the individual houses together.

In retrospect, in 2000 when Chen Zhen was sick, he insisted that I finish these candle pieces. He would say, “Make them by my side while I sleep in my bed.” I never really understood what he meant. Now that I think about it, though, I think he wanted me to continue and finish this project for him, which is why he had me practice while he could still be there to watch. Each and every one of these houses is an impromptu piece—there was no way of planning or sketching beforehand. When he was hospitalized, he took care to tell me, “Xu Min, these pieces are really nice, but burning the candles harms the lungs, and so you shouldn’t finish them all. Just make half of them.” After Chen Zhen died, some friends encouraged me to finish the project, and so I hired an assistant and finally finished it two years later. I felt like I had fulfilled a very precious dream of his, while honoring his last words.

How did Chen Zhen handle his disease? Did coming from a family of doctors affect his work as an artist?

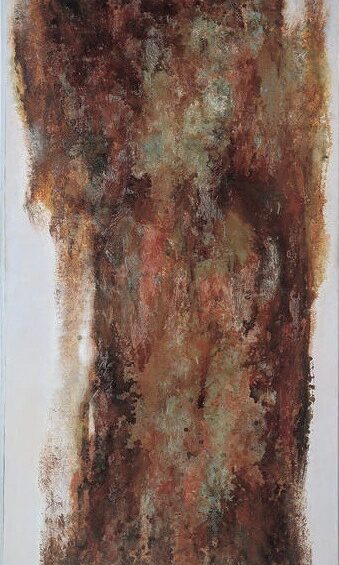

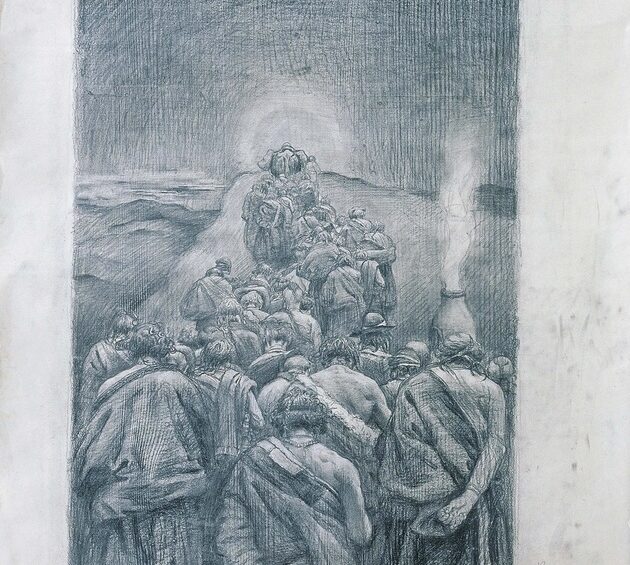

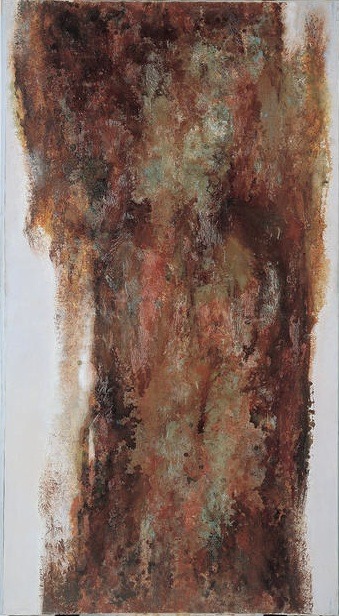

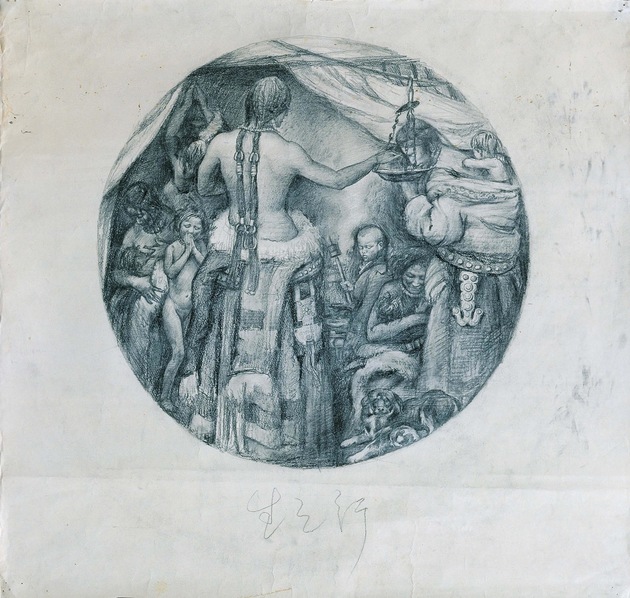

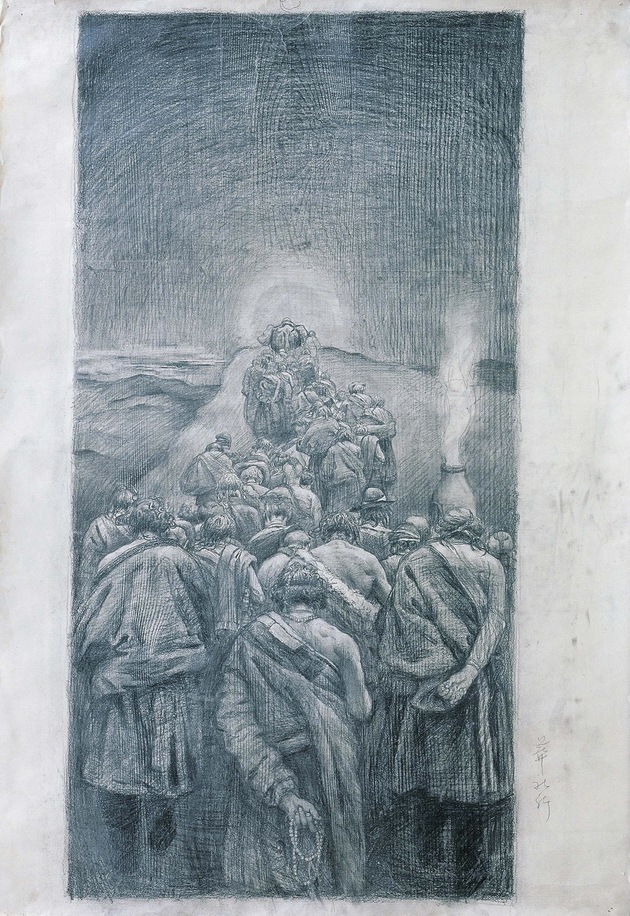

Floating Qi was painted after Chen Zhen got sick in 1985. Sickness undoubtedly hit him hard. He was a person who shone in his energy, and yet he was confined to bed rest. He wanted to strengthen himself from within, and so he read many books on philosophy. We even traveled to Tibet, where the blue sky and the white clouds felt like they were within reach, and we were awed by the greatness of nature. He would constantly tell me, “One must concede his spirit to nature, so that one may overlook trivial personal problems.” He had to set aside his sickness, his pain, and his individuality in order to devote himself completely to creating art. After that, he painted The Birth (1983), The Deceased (1983), and The Pilgrimage (1983).

Coming from a family of doctors and scholars, Chen Zhen certainly faced some objection when he announced he wanted to pursue art. But the truth is, there weren’t that many options available during the Cultural Revolution; you either went to work at a factory or you went to the only school available—Shanghai School of Arts and Crafts. Chen Zhen loved sports; he was a fast runner, with an impressive track record of 11 seconds for 100 meters—that was close to the world record at the time! But he hurt his ligaments in a race, and the doctors declared him unfit to run anymore. This was the end of any prospects of a career in sports, and so he learned how to paint. At first his parents felt like he was fooling around, and so they weren’t quite supportive, but they weren’t too against it either. They would often ask Yen Guoji, his sketch teacher, behind Chen Zhen’s back, “Does our son show any talent in this field?” They had always felt that Chen Zhen didn’t work as hard and as seriously as his brother, and yet he continued to perform well in school. He earned high grades in all of his subjects, and especially in math. He was the youngest, smartest kid in the family, but also the one who fooled around the most. He used to sneak out of the house after coming home from school, which often got him into trouble. In a sense, he had always felt that he wasn’t understood; when we were dating, he would constantly say that he was sure he would achieve something great someday. After he left for Paris, he made Round Table (1995)—and that piece of art shocked his father.

His father understood this piece immediately; it brought him closer to his son, and the two of them started communicating about art. His father said, “You have a really nice piece of art here. Its visual language is simple, but addresses ambitious, universal themes about equality and peace.

Chen Zhen’s works were often infused with a persuasiveness, raising societal questions like, “Have you ever thought of what the consequences of this will be?” He enjoyed analyzing the relationship among humans, nature, and objects. His theory was that people are so filled with desires that they create an overflow of material objects, harming nature on the way, and that as a result, nature fights back, which creates a vicious cycle. He was also interested in “identity issues.” This came from his constant reflection: “As a Chinese artist living in Paris, how do people see me? When it comes to identity, what ground do I stand on? What am I giving up, and what should I give up so that I may become a liberal on this worldwide stage, or stand like a proud nomad who isn’t confined to any homeland?” He felt blissful to have been alive in this era of globalization, and thought of Paris as a mere stop along his way across the great world. Deep down, he admitted to harboring the arrogance of a man who comes from a great country like China. In addition, he deeply admired Mao Zedong’s poetry, believing that no other leader has ever had the kind of broad mind required to write such poetry.

The day before Chen Zhen died, there were no signs at all that the end was near. He didn’t utter a word; he never bid farewell, nor did he leave any instructions. After he passed away, I had to deal with many things based on my own ventures, especially since he used to be the one handling most of our external affairs. He had always been an optimistic man with strong survival instincts; when we lived together, I hardly ever felt like I was living with a sick man. But in 1999 he told me, “Xu Min, I feel like I’m slowly killing myself with all the pills I must take every day. I think perhaps science will never catch up with my disease, and there won’t be a cure found during my lifetime. Perhaps the only thing left to do is to treat my body as a lab for experiments, to find some shaman or sorcerer to try to treat my body. Is it possible that in this world there is something still unknown to us that may be the cure to my sickness?” He had the idea of a medical project—he wanted to communicate with the world through traveling and interviews, and to heal the sickness within our society, the sickness of human mentality, and even his own sickness with it. He did the project In Praise of Black Magic in 2000, in Turin, Italy. There was a lady whose leg pain wouldn’t go away; on the day of the opening of the exhibition, she stood in the gallery for two hours and her leg just magically stopped hurting. I almost doubted the miracle, but there she was, thanking Chen Zhen elatedly. I did a retrospective exhibition based on this theme in 2005, in Greece. Unexpectedly, many medical school students lined up to buy tickets to see the show.

How did Chen Zhen present “time” in his works? Did his awareness of his sickness impact his works at all? Did his works reveal a sense of confinement by “time”?

I am sure this was a theme on his mind, but he wouldn’t obsess over it; he poured all his energy into art. He was well aware that his was walking on thin ice when it came to health and that he was fighting against time. He wouldn’t explicitly say it, but you could tell from how he made sure he cherished every minute of each day and worked hard. He spent time dining out with our family, but sometimes he would say, “Xu Min, you know, I could have replied to ten e-mails during this time.” After all, he was a very busy man. Other times he would be lost in thought, and then turn around and ask me, “Xu Min, do we eat to work or work to eat?” I would say, “What do you think?” He would say, “Well, I certainly eat to work!” When I said, “But many people think that you work so you can eat better and dress better,” he would reply, “For me, I would love to not have to eat. Imagine all the extra time I would have!” To Chen Zhen, the only thing that brought him happiness and meaning in life was work.

How did Chen Zhen’s last solo exhibition come about?

In 2000 the Italian art gallery—Galleria Continua—bought a movie theater that became the venue for Chen Zhen’s last exhibition while he was alive. It was a complex space, with hallways, stairs, the box office, and so on. Chen Zhen analyzed the space and said, “It is pretty hard. I either have to utilize all the space or give up on this idea all together.” The task was strenuous. By that time, it seemed to me that he was overwhelmed and losing his grasp of things. He began to postpone everything, and I didn’t understand why. This project started with clay sculpture, which meant a lot of work in plaster molding and making small models, and so I said, “If you keep on going like this, we will run out of time. Why don’t we just pick it up and do it? Don’t overthink it.” However, I felt like he was passive and reluctant. In retrospect, by that time, the cancer had already spread to his whole body, and so I was basically pushing and coercing a sick patient. The process was really hard on him; he had to paint on his knees, and he was barely able to hold up his back. I thought the pain was from all those years of hormone treatment finally catching up with him, making his body uncomfortable during the exhibition. His parents sent us packages of Chinese herbal medicine and I helped him apply it; we never thought it was cancer—we just assumed it was osteoporosis or a neck and back injury. During the installation, Chen Zhen went to the emergency room twice for pain medication. After the injections, he would say, “Xu Min, I can jump up and down like a kid again!” And yet four hours later, the pain would again be unbearable. He couldn’t sleep lying down—he often slept standing up. I would fall asleep due to exhaustion, and I would wake up in the middle of the night and see him standing in his sleep. I wondered what he was thinking. He told me, “It hurts right to the core!” And, in fact, it was his spine hurting.

The day he was told he had cancer—he was the one who answered the phone. The doctor who called gave him the news bluntly. Artist friends Wang Du and Yan Pei-Ming had come over to visit him, because they had heard he was suffering back pain. I told them, “It is dinnertime already, and so why don’t you stay? I will make us dinner.” Meanwhile, Chen Zhen was napping alone in a room upstairs, and he got the call from the doctor. We didn’t even know about it. Afterward, he came down for dinner—acting aloof and casual—and simply said, “Let’s eat.” I was quietly wondering why the doctor hadn’t called yet—for he should have already—and I wanted to call him. Chen Zhen stopped me and said, “Don’t. The doctor has already called.” I was shocked and wordless, for instantly I knew there was something wrong. So I said, “What did the doctor say?” He said, “Xu Min, just imagine the worst case scenario.” I thought to myself —it must be cancer! What could be more devastating? And so I asked, “Is it cancer?” He replied calmly, “Yes.” Wang Du and Yan Pei-Ming were astonished, and I couldn’t help but burst out crying. But Chen Zhen tried to pacify me; he said, “Don’t cry. There’s been so much medical progress. I’ll make it through.” After our friends left, I said, “Let me go buy you some pain-killers. You are running out of those.” Chen Zhen replied, “Wait, I’ll come with you. I don’t ever want to leave you again.” It was an utterance filled with such emotion! I helped him to the car, and we drove to the pharmacy to buy pain-killers. Then I told him, “Chen Zhen, there will be a miracle for you, I can feel it. Others might not make it, but you will.” In a sense, I guess I was naïve, always caught up in wishful thinking. That night, we slept particularly soundly, holding hands in our sleep. The next day it was time to battle. Our assistant came to work as usual, to burn newspapers for a project we were doing. I told the assistant, “I have to drive Chen Zhen to the hospital, and so why don’t you go home? But before you leave, could you take a few pictures of us?” I had a feeling Chen Zhen was not going to be returning home again. And just like I feared, Chen Zhen passed away three weeks later. The staff from Gallery Continua was there by my side all the way. They had come to know Chen Zhen, and they felt it was a blessed friendship. They felt truly sorry that Chen Zhen had left us before the exhibition was even over. They were devastated by his death, too, and since then, they have never given up on Chen Zhen’s legacy, helping me to arrange several retrospective exhibitions, helping with the installations and all. I had sworn to myself that I wouldn’t sell a single piece of Chen Zhen’s legacy for five years. I spent the first three writing books, and also focused on restoring his works and arranging his retrospective exhibitions.