In this essay, Guillermo S. Arsuaga presents a critical examination of architectural modernism through the lens of one of the most renowned examples of modern architecture in Africa: La Pyramide designed by Italian architect Rinaldo Olivieri in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast). His meticulous study of Olivieri’s unique photographic record of the project, the focus of which is predominantly the construction process, offers a nuanced understanding of modernism, one that transcends traditional architect-centered narratives. Olivieri’s images reveal a compelling emphasis on the integral role of African labor and the network of expertise and materials active in shaping the building, a perspective often overlooked in conventional architectural studies. Arsuaga underscores the significance of recognizing these elements, of viewing architecture not merely as a physical structure but also as a complex confluence of human endeavor, resources, intellect, and societal forces. He argues that such an understanding of modernism, one embracing the pivotal contributions of laborers from the continent, fosters a more nuanced narrative of architectural history. He concludes with a call for further exploration of the roles of these underrepresented agents across diverse architectural projects and contexts as a means of enhancing narratives and understanding of architectural history and modernism.

In February 2023, I visited the residence of Rebecca Olivieri on the banks of the Adige River in Verona and the private archive dedicated to her father, Italian architect Rinaldo Olivieri (1931–1998), who significantly shaped Abidjan’s architectural landscape in the nascent independent Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast). His most significant work, La Pyramide (The Pyramid), is a highlight of so-called African architectural modernism—the architectural materialization that emerged in diverse forms across the continent as a result of the convergence of modernity’s aspirations and the quest for national identity catalyzed by the wave of African independences in the 1960s and 1970s.

While discourse on African architectural modernism—especially its implications for postcolonial emancipation—has proliferated in the last few years, Olivieri’s private archive offers a unique perspective on La Pyramide.1On “African modernism” as it applies to the architecture that emerged as a symbol of newly independent nations in Africa during the second half of the twentieth century, see Manuel Herz, “The New Domain: Architecture at the Time of Liberation,” in African Modernism: The Architecture of Independence; Ghana, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Zambia, ed. Ingrid Schröder, Hans Focketyn, and Julia Jamrozik (Zurich: Park Books, 2015), 5–15. Indeed, it foregrounds labor and materiality, sharpening our understanding of modernism’s intricacies and the networks underpinning its manifestation in a newly independent Côte d’Ivoire.2On the role of architecture in postcolonial Africa, see, for example, Herz et al., African Modernism; Nina Berre, Johan Lagae, and Paul Wenzel Geissler, eds., African Modernism and Its Afterlives (Fishponds, Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2022); Tom Avermaete and Maxime Zaugg, eds., Agadir: Building the Modern Afropolis (Zurich: Park Books, 2022); and Ola Uduku, “West African Modernism and Change,” chap. 8 in Time Frames, ed. Ugo Carughi and Massimo Visone (New York: Routledge, 2017).

Olivieri undertook the project of building La Pyramide in 1972, following design commissions for the pavilion, Cote d’Ivoire, at the Japan World Exposition in Osaka in 1970 and the Istituto Tecnico Industriale in Verona in 1966. Located in the heart of Abidjan, in the district of Plateau, La Pyramide was introduced as a departure from the prevalent glass-and-steel constructions imported from Europe that had proven unsuitable in Cote d’Ivoire due to the country’s intense sunlight and need for consistent air conditioning.3Paolo Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan, Costa d’Avorio,” L’Architettura: Cronache e storia, no. 214/215 (August/September, 1973): 186.In other words, it was looked upon as a form of architectural modernism specific to the Ivorian context.4Claudio Di Luzio, Rinaldo Olivieri: Architettura come luogo della memoria (Bari: Edizioni Dedalo, 1993), 55.

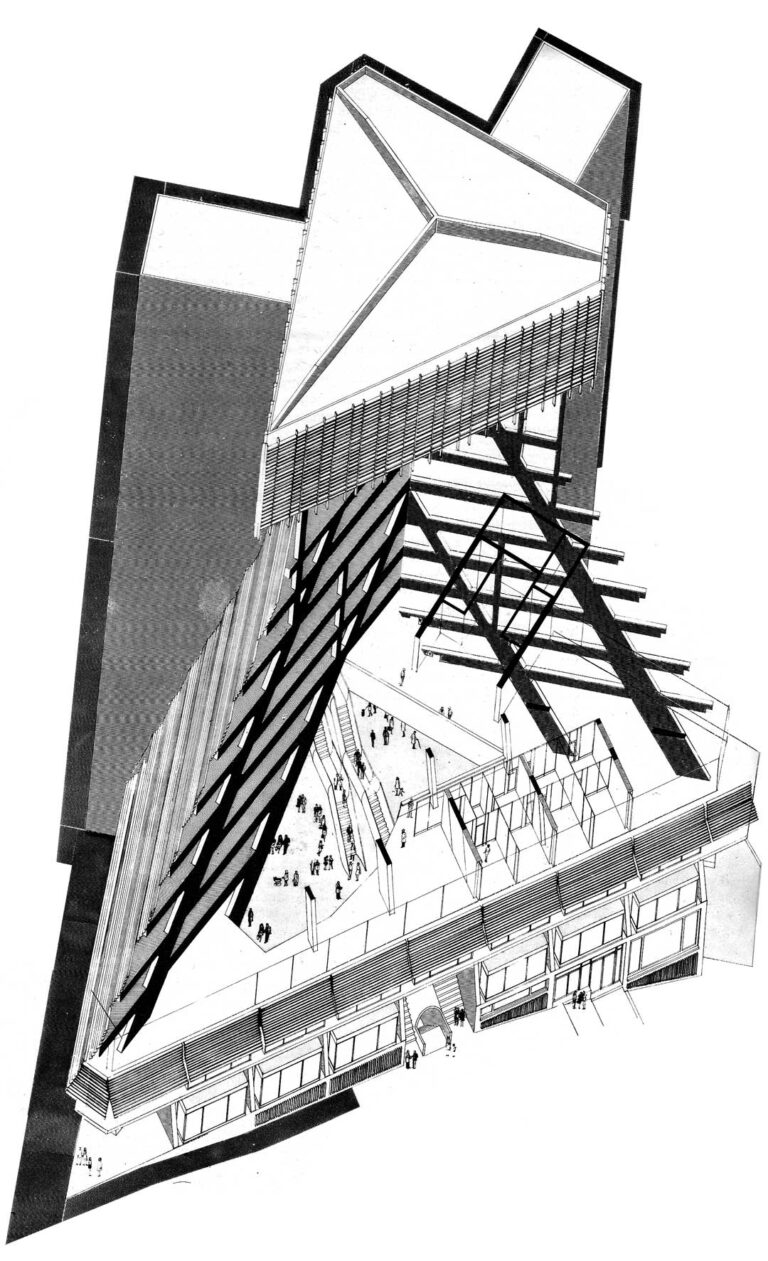

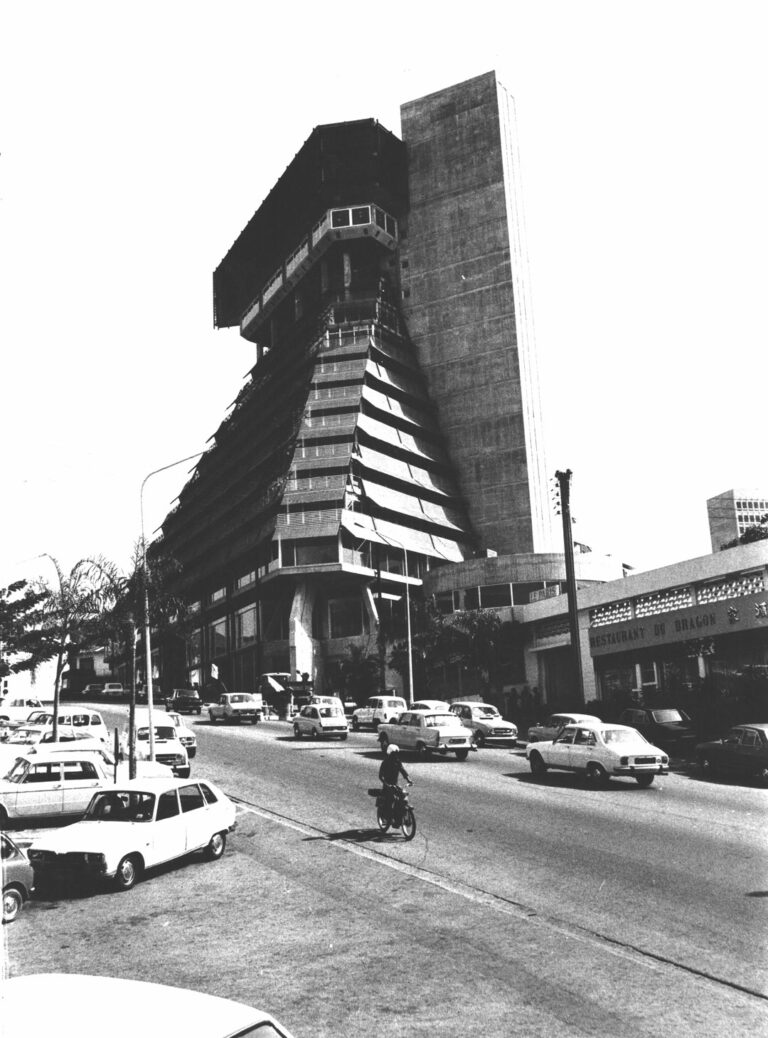

Commissioned by SOCIPEC, the first fully Ivorian real estate company, and funded by the National Financing Company, the project unfolded over three years, from 1970 to 1973.5On the financing of the project, see Ben Soumahoro Mamadou, “Côte d’Ivoire incendie de la Pyramide—Ben Soumahoro accuse . . . et fait l’historique,” Connection Ivoirienne (blog), May 1, 2018, https://connectionivoirienne.net/2015/06/29/cote-divoire-incendie-de-la-pyramide-ben-soumahoro-accusse-et-fait-lhistorique/. On SOCIPEC being “the first entirely Ivorian real estate company with state participation” (my translation), see Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan,” 186.Initially named “Centre commercial ad Abidjan,” the building quickly earned the affectionate moniker “La Pyramide” among Ivorians due to its pyramidal form.6Rebecca Olivieri, interview by author, February 2023, Verona.Once finished, the building became a visual landmark. Moreover, within its 234,600 square feet (21,800 square meters), it fulfilled a range of functions associated with modern urban life, including providing office spaces, studios, a restaurant, an exhibition space, an auditorium, a parking area, a nightclub, and a supermarket. La Pyramide’s dominant triangular plan and truncated pyramidal volume, structurally made in reinforced concrete, rises more than two hundred feet (sixty-one meters) and spans fifteen floors (fig. 1).

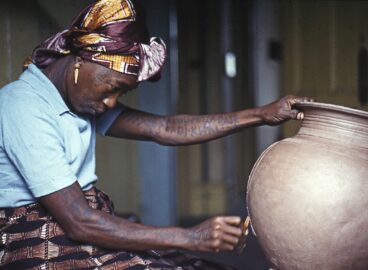

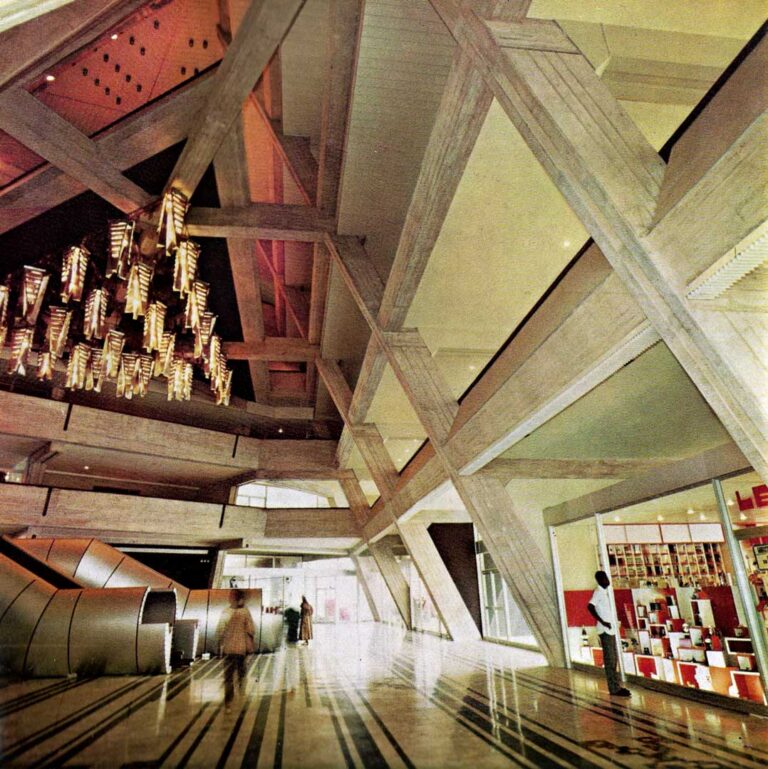

According to Olivieri, La Pyramide’s distinctive shape, far from a pure geometrical composition, draws from a formal abstraction of precolonial African bird figurines.7Olivieri, interview by author.The interest in anchoring the building in African culture was reinforced in Olivieri’s reference to his conception of La Pyramide as a “large covered market,” in effect a modern reinterpretation of the traditional African market, which served similarly important social and cultural functions.8For discussions on La Pyramide as a “large covered market” and its symbolic role in African society, see Bassani, “Centro Comerciale ad Abidjan,” 182, 186–87. This endeavor is architecturally evoked in the multilevel central hall, a daylight-infused space and the building’s commercial and social hub (figs. 2 and 3). At the same time, this main hall functioned architecturally as a key organizational space, facilitating access to various levels encompassing offices and commercial areas, all visually connected within the hall (see fig. 3). This space is illuminated by natural light, which, in conjunction with the suspended concrete walkways, contributed to a visibly engaging design. Indeed, Olivieri described these elements as facilitating “evocative” interplays of light and space, a concept inspired by the drawings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778).9Olivieri’s use of light and space as influenced by Giovanni Battista Piranesi is discussed in Di Luzio, Rinaldo Olivieri, 54. Piranesi was an Italian artist known for his etchings of Rome and, in particular, a series of plates titled Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons).

The central hall is perhaps the most architecturally experimental aspect of La Pyramide, in effect reversing the characteristics typical of a building’s core. Traditionally dark and secluded, this space is instead a light-filled, gathering place. It simultaneously offers shelter from sun and rain, drawing inspiration from the dynamic ambiance of traditional covered outdoor markets (see fig. 2, 3 and 13).

The layout of La Pyramide is programmatically articulated, characterized by a stratification of spaces by their intended use. The first twelve floors were designed to contain offices, retail venues, and studios, which are arrayed in a triangular perimeter across suspended walkways that surround the central hall—enhancing its role as a center for social and commercial exchange.

At the heart of the building, on the third floor, an exhibition room appears to be suspended within the central hall. The thirteenth floor, which was dedicated to a restaurant, provides a panoramic view of Abidjan and Ébrié Lagoon, and an auditorium on the fourteenth and fifteenth floors crowns this main volume.

Attached to the pyramidal space, two vertical towers contain the elevators, stairs, and bathrooms—thus freeing up space in the central hall (typically, a tall building would incorporate these infrastructural elements in its core). Above the ground floor, between one of the towers and the main volume, a circular extension that once housed a snack bar cantilevers toward the street. The three-level basement of La Pyramide originally included, top to bottom, a supermarket, a nightclub, and a parking lot.10Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan,” 182–93.

An outstanding architectural feature of the exterior is the aluminum components that Olivieri employed in contrast to what is otherwise raw concrete. Explained as a climatic adaptation, these metal elements wrap horizontally around the facade in the form of brise-soleils that not only shield the glazed side but also the outdoor walkways extending across three sides of ten levels of the building.

The Evolving Modern Legacy of La Pyramide

The initial aims of modernity and La Pyramide have decayed over the years. Once hailed by the architectural press as a significant exemplar of Ivorian architectural emergence, the building now stands in a state of neglect. Since the 1980s, it has remained largely unoccupied and closed to the public, owing to the high costs associated with its maintenance.11Oliver Wainwright, “The Forgotten Masterpieces of African Modernism,” The Guardian, March 1, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/mar/01/african-modernist-architecture.Nevertheless, there are ongoing initiatives focused on its repurposing and restoration that give new hope to the revival of the structure.12“La Côte d’Ivoire en chantier: ouvrages, édifices, équipements . . . – Les 27 projets qui vont tout changer!,” @bidj@n.net, September 22, 2011, https://news.abidjan.net/articles/411345/la-cote-divoire-en-chantier-ouvrages-edifices-equipements-les-27-projets-qui-vont-tout-changer; “The Future Was Born Yesterday,” Street Art United States, May 23, 2023, https://streetartunitedstates.com/the-future-was-born-yesterday/ « La Pyramide d’Abidjan : un trésor brutaliste qui se réveille pour briller à nouveau »,” Sunuculture (blog), October 19, 2023, https://sunuculture.com/2023/10/16/la-pyramide-dabidjan-un-tresor-brutaliste-qui-se-reveille-pour-briller-a-nouveau/

Amid discussions of the future of La Pyramide, Olivieri’s project archive in Verona, until now largely unexplored, offers a window into not only the intricate ideation and construction of the building but also the role of architecture in mediating the relationships between representation, labor, and materials in an incipient Ivorian nation.

Ascending to the second floor of the palazzo in Verona, one encounters a realm in which Olivieri’s memories and works have been carefully preserved by his daughter, Rebecca. These tangible remnants of the architect’s legacy—photographs, sketches, architectural models, and press clippings—all of which he brought back to Italy upon concluding his professional work in Abidjan, where he moved with his family, spent several years in residence, and acquired Ivorian nationality.13Olivieri, interview by author.Various drawings—watercolors, pencil sketches, and Conté crayon renderings—adorn the walls, each silently attesting to Rinaldo’s drawing proficiency. Yet, within this vast repository, there is an unmistakable absence—there are no drawings or blueprints of La Pyramide, the architect’s most celebrated creation (and the reason for my visit).

Rebecca suggested that most large-size architectural renderings from the 1970s, including those of La Pyramide, might have been challenging to transport from Abidjan, and therefore left behind. As I explored the boxes dedicated to the project, I confirmed the glaring absence of what many architects regard as foundational to architectural documentation: original drawings, which are (to a certain extent) present among the records of Rinaldo’s other projects related to Côte d’Ivoire, such as the Osaka Pavilion and San Pedro Airport city. Rinaldo’s archive for La Pyramide instead sparkles with black-and-white photographs—some showcasing early models, others recording the completed building, and still others making up an extensive series chronicling the construction process. While I browsed these photographs, Rebecca mentioned Rinaldo had shot the images taken on-site himself. Alongside these were a few 11 x 8 1/2–inch photocopies of drawings of La Pyramide and some sketches of the same dimensions—quite different from the drawings an architectural office would traditionally produce.

This revelation is particularly striking against the backdrop of traditional Western narratives of modern architecture, in which the architect is lauded as the singular genius behind innovation and aesthetic excellence. Such accounts are sustained by a reliance on the architectural archives and full-scale drawings commonly thought to preserve the architect’s original intentions and the intellectual interests that inspired them. Yet, the collected artifacts related to La Pyramide lack such “original” or full-scale drawings, typically the cornerstone of an architectural archive, suggesting that there are missing pieces in terms of the building’s architectural history.14While architectural photography, especially images of the “construction” process, has been very much linked to the birth of modern architecture and the focus on industrial materials such as iron and glass and quick construction techniques (for example, Philip Henry Delamotte’s 1854 photographic documentation of the reconstruction of the Crystal Palace, Progress of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham), it has been primarily viewed as reinforcement or continuation of the architect’s aura, that is, of how their initial designs were realized and materialized. See, for instance, Ian Leith, Delamotte’s Crystal Palace: A Victorian Pleasure Dome Revealed (Swindon, UK: English Heritage, 2005).

Upon closer scrutiny of the available material—predominantly construction photographs—I discovered an opportunity to understand the architectural process behind La Pyramidein a new light. I found myself enthralled by the idea that these pictures, in their plentiful number and varied perspectives, provided something significant about Olivieri’s view of the project. This was not just a smattering of images but nearly 150 photographs—some duplicated, some cropped, some refocused, and some reformatted. First, they were taken by the architect himself, making them a direct trace of what he thought was worth recording and of his main preoccupations while engaged in the project. Second, there was a postproduction process within the selection as is evidenced by the cropping and crossing out of images recorded in dozens of contact sheets. And, finally, these photographs—among the presumably many documents Olivieri could have saved to illustrate the project—were the ones he chose to transfer from his studio in Abidjan to his house in Verona. In short, at that point, I realized, most likely for him, these images likely encapsulated for him a more holistic depiction of the project than any one drawing could.

Surveying Olivieri’s photographs of La Pyramide, many of which depict African laborers at work, one is immediately struck by the dual nature of the imagery. On the one hand, this focus can be seen as embodying the colonial viewpoint of a European architect capturing African labor though his own lens. However, on the other, in terms of tracing the history of the building, it unfurls a network of diverse involvements, revealing the intricate meshwork of hands and minds that forged the building’s existence, shedding light on the complex interplay of roles and thereby enriching our architectural discourse. In this sense, Olivieri’s images can be interpreted beyond a binary perspective, one that sees them as either an imperial tool or an instrument of liberation. They are, in fact, tools in illuminating the active roles and perspectives of laborers and other participants in the construction process, in prompting a critical examination while acknowledging the underlying power dynamics and colonial implications.15Photography has historically served dual roles: On the one hand, it has been a tool of modernity, empowering individuals in postcolonial African settings to shape and express their identities. On the other, it has been used as a means of imperialism, with foreign powers capturing images that sometimes misrepresent or control the narratives of colonized regions. For further reading on these dual aspects of photography, see James Barnor: Stories; Pictures from the Archive (1947–1987), exh. cat. (Paris: Luma Foundation, 2022); Erin Haney, Photography and Africa (London: Reaktion Books, 2010); and John Peffer and Elisabeth L. Cameron, eds., Portraiture & Photography in Africa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

The photographs in the collection provide a rich chronicle of the construction process, including of the site, the materials and techniques employed, and especially the labor engaged throughout the project. Who were these workers? Were they Ivorian locals or brought in from afar? Were they West African migrants? How many hands contributed to this task, and under whose directive? While the photographs housed within the Olivieri archive may not answer all of these questions, they undeniably suggest a more multifaceted understanding of African architectural modernism.

These images invite a shift in perspective—one that steps away from the single authorship of the architect and toward an understanding of a building as the result of a collaborative effort. Rather than perpetuating an architect-centric narrative, this view sees the architect as one part of a broader constellation of contributors within a network encompassing power dynamics and economic, cultural, and social factors, thereby offering a more nuanced architectural history, one that intersects with discourses on labor, materials, colonial legacies, and postcolonial aspirations.

Modern Narratives: Olivieri’s Photographic Chronicle of La Pyramide

That February day in Verona, as I flipped through Olivieri’s images, I saw that they had been chronologically organized, from the foundation excavations to the building’s final rise. Looking at the architect’s numerous images of the foundation, I sensed his fascination with the choreography of laborers, tools, and materials involved in the initial excavation. To be sure, these images reveal less of an abstract void than of a pulsating node of human endeavor. Indeed, later, in a coffee-scented interlude, the late architect’s widow, Isabella, tenderly shared memories of Abidjan.16Isabella Olivieri Lonardi, interview by author, February 2023, Verona.Revisiting her first brush with a vast excavation—destined to become the basement of La Pyramide—she reflected on this being the inaugural spectacle Rinaldo had elected to unveil to her upon her arrival to Abidjan.

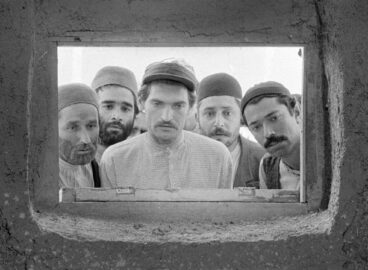

Within the images of the excavation and setup of the foundation, one image particularly struck me: It depicts a massive cubic void, some sixty feet deep, punctuating the earth, and shows five African laborers at work (fig. 4). Four are in the bottom of the trench, engaged in the fundamental acts of digging and earth removal. Another ascends a ladder, contributing to the emerging verticality that hints at what will become La Pyramide.

In looking at this photograph, I began to discern Olivieri’s active role in shaping the narrative of LaPyramide’s construction. The scale of the excavation is underscored by the individual efforts of the laborers who, using manual means, appear to effortlessly carve the clay-rich soil, which stands vertically, defying the need for support. The framing of the photograph further intensifies this perception, with the void almost five times higher than the workers—beyond the reach of a ladder. However, one can discern the role of heavy machinery by the subtle tire marks visible on the ground. This equipment, I surmise, was consciously excluded from the frame. By choosing to highlight the monumental scale of the carved void alongside intense manual labor, and simultaneously omitting the machinery that typically would be involved, Olivieri, whether consciously or unconsciously, revitalized the role and agency of these laborers within the grand narrative of the building’s construction.

Fig. 5. Rinaldo Olivieri, La Pyramide construction site, Abidjan, 1972; Rinaldo Olivieri Archive, Verona, Italy. Copyright © Reinaldo Olivieri Archive.

Consider another photograph depicting five laborers assiduously arranging rebar into a sharp hexagonal cast-in-place footing anchored within the soil (fig. 5). Visible in the right-hand side of the image, the concrete truck’s chute stands ready for a pour while its delivery is guided by a handcrafted wooden support system. Yet again, the heavy machinery, both the truck and the mixer, are outside of the frame, focusing the viewer’s attention on the workers themselves and the craftmanship of the pristine geometrical footing.

While construction is inherently collaborative, Olivieri’s emphasis on this expansive agency in his archival record present in these photographs offers an opportunity to highlight the role of African workers. Moreover, it provides a critical lens through which to challenge the oversimplified single-author narrative that has, at times, dominated architectural discourse.

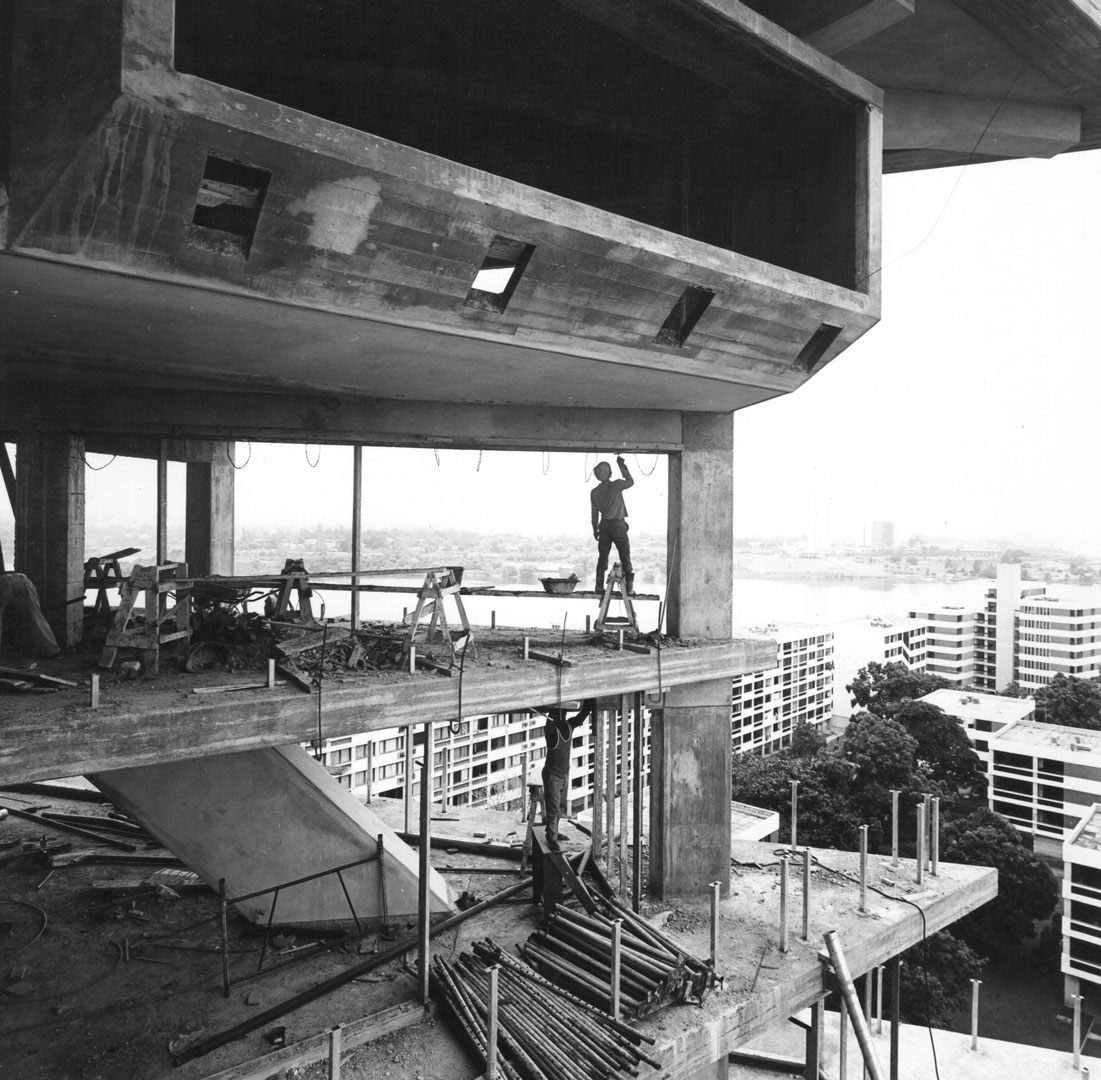

As La Pyramide rose from its foundation, Olivieri’s photographic effort was unwavering, particularly toward the intricate interplay of main structural components imported from Italy and assembled by African craftsmen in Abidjan (see fig. 6 and 7). In his photographic chronicle, he captured the dynamic between industrial-engineered structural elements designed by Riccardo Morandi (1902–1989)—a leading figure in reinforced concrete work in Italy—and their nuanced integration and assembly by local hands.17On Morandi’s contributions to the concrete structure of La Pyramide, see Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan,” 186. Rather than isolating these construction elements in the manner of detached, abstracted representations of engineering or architectural objects, Olivieri continuously anchored them in relation to the African labor force, rendering this construction history within a broader context. This decision provides a perspective on a long-standing question in the history of architectural modernism: how global designs, networks of materials, and labor relate to the local landscapes and communities in which they are realized.

Take, for instance, the photograph in which Olivieri purposefully captures an African worker meticulously retouching a beam on La Pyramide’s uppermost level (fig. 8). Far from the result of a random snapshot, the composition is orchestrated to mirror the structure of the neighboring pillars and to highlight the laborer’s contribution. Standing tall, he brushes the underside of a ceiling beam, fresh from the removal of the supporting forms and shoring that supported the concrete during curing. Within the scene, a second workman dismantles the shoring on the floor beneath. This picture, set against the panorama of Abidjan’s Ébrié Lagoon and an array of modern residential buildings, suggests that Abidjan is not just in the process of being transformed but already the embodiment of modernity. Once again, whether consciously or unconsciously, Olivieri’s framing juxtaposes the realities of the laborers against the emergence of a modern Abidjan, reiterating the indispensable role of African laborers in shaping this perception.

Beyond the Frame: Reimagining Modernism through La Pyramide

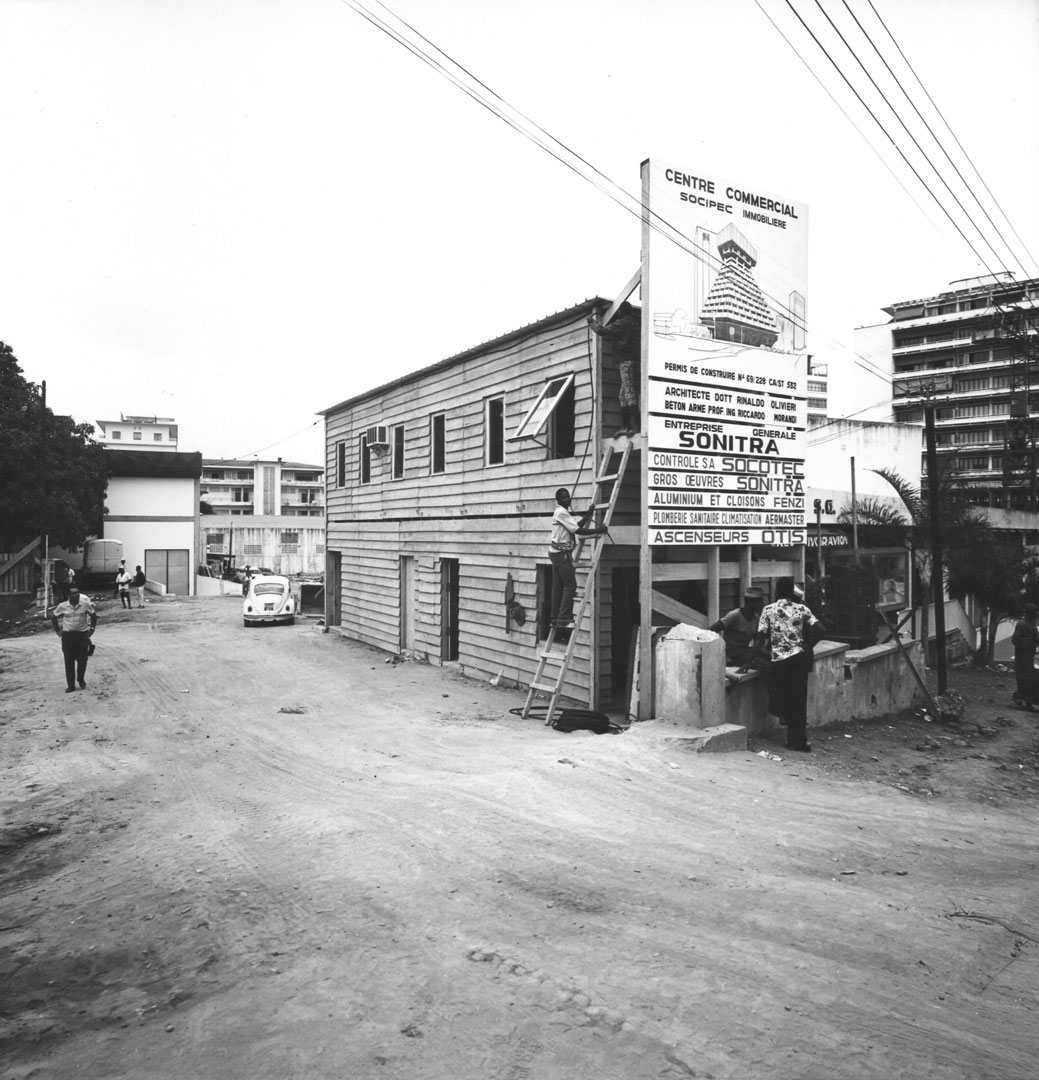

As I delved deeper into the recesses of Olivieri’s archive, a previously overlooked photograph captured my attention. The image showcases a group of African workers ostensibly engrossed in setting up temporary lodgings for La Pyramide’s workforce (fig. 9). Yet it was not their labor that captivated me, but rather the billboard prominently situated in the foreground. Towering at twenty-four feet, it bears the inscription “Centre Commercial SOCIPEC IMOBILIERE,” which is set above a depiction of La Pyramide. Intriguingly, the sign also delineates the diverse entities involved in the construction La Pyramide—architect Rinaldo Olivieri, concrete engineer Ricardo Morandi (who, like Olivieri, hailed from Italy), Sinitra (the Ghanaian construction firm trusted with the majority of the construction), Socotec (a French entity charged with supervision), Fenzi (a Northern Italian firm supplying aluminum and window frames), and Otis (the American titan responsible for the elevators).

I realized this picture captures the core of the power dynamics between various agents and initiatives during the construction of La Pyramide. It renders the dominance of so-called European technical expertise (such as that of Olivieri, Morandi, or Fenzi) juxtaposed with nascent African companies within the new nation-state framework (such as SOCIPEC and Sinitra)—all of which is juxtaposed with the African laborers setting up their temporary settlement.

Discovering multiple iterations of this image in Olivieri’s collection piqued my curiosity. Why had Olivieri repeatedly chosen to photograph this particular scene? Perhaps because it encapsulated the role of La Pyramide within African modernism more effectively than any other—a role defined not by its scale or use of aluminum and concrete, but rather by the dynamic convergence of labor and technical know-how and the African endeavors toward modernity that brought it to life. Concurrently, this construction narrative, coupled with the initial idea behind the building—to reinterpret the rhythms of the traditional marketplace by infusing local commerce with modernist aesthetics and spaces—perhaps evidences the complexities, paradoxes, and contradictions of architectural African modernism and its contested role in the continent’s time of self-determination and the different experiences and subjectivities, from African workers to European technicians, that it entailed.

This exploration leads to broader contemplation within the field of architectural history, which has often overlooked non-Western geographies such as Africa.18The “field of architectural history” refers to the widely recognized and accepted body of work that historically has been given prominence in the study and teaching of architectural history. It predominantly includes works, theories, and practices that have originated or been celebrated within Western academic and cultural spheres. An expansive reassessment of modernity that transcends a Western-centric focus demands a reexamination of both the architect’s role and the presumed objectivity of archival materials within the larger narrative of architectural modernism. Far from being an obstacle in the task of writing history, this broader scope offers fertile ground for inquiry within a canon traditionally dominated by Western perspectives. The realms of architectural practice, such as labor, that typically have been marginalized within mainstream discourse provide vital alternative viewpoints, cultural richness, and distinct architectural frameworks that challenge and subvert the dominant Western-centric ideology of the architect’s realm. As a result, both the architect’s contributions and the very shape of architectural archives take on a nuanced complexity, defying simple categorization.

This shift away from monolithic understanding enhances the possibility for a more inclusive reading of architectural history. It offers a fresh view of modernist architecture and underscores the diverse agents who influenced its trajectory. It encourages a broader understanding of a building, one extending beyond aesthetics and construction, to consider it as a reflection of prevailing power structures, aesthetic norms, economic conditions, labor practices, and material uses. A deliberate pivot from the architect as the central figure allows the emergence of the lesser-acknowledged agents often eclipsed in Western narratives. This reorientation invites a more expansive vista of the modern canon, one that welcomes those in previously shadowed roles.

In this sense, Olivieri’s photographs foster an understanding of modernism that extends beyond the physical edifice . They underscore a collective action that interweaves the builders, materials, and users, nurturing an evolving African modernity. This perspective, though it might seem logical at this point, significantly differs from earlier portrayals of the building, such as its depiction in the 1979 MoMA exhibition Transformations in Modern Architecture, in which the building was predominantly presented as a finished object lacking human interaction, and in the L’Architettura magazine article of 1973, which similarly depicts the project.19Curated by Arthur Drexler, Transformations in Modern Architecture opened at The Museum of Modern Art on February 21, 1979, and ran through April 24, 1979. This exhibit critically explored the evolution and impact of architectural ideas and styles from the 1960s through the late 1970s, highlighting pivotal developments in modern architectural thought and practice. See Arthur Drexler, Transformations in Modern Architecture, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1979). For more on the 1973 article Bassani, “Centro Commerciale Ad Abidjan.”

Olivieri’s repository opens up La Pyramide as an important architectural story focused not only on the physical construction or finished image of a building but also on the relationships and shared goals that contributed to its creation. Much like my rendezvous with the Olivieri compendium in the serene Veronese residence, these images present more than a chronicle pertinent to African architectural modernism. They unveil a distinct lens, opening a window onto a broader understanding of modernism. They underscore how an architect’s trove might not just document but also catalyze expansive dialogues on oft-neglected entities such as labor, which are pivotal to the modern narrative. Through Olivieri’s photographs, these elements are not peripheral musings on his African modernity and architectural oeuvre, but instead a fundamental framework within which to disentangle the intricate networks of modernism.

Special thanks to Isabella Olivieri Lonardi and Rebecca Olivieri for their generosity in sharing the archive and their insights during our interviews, which greatly enriched this research.

- 1On “African modernism” as it applies to the architecture that emerged as a symbol of newly independent nations in Africa during the second half of the twentieth century, see Manuel Herz, “The New Domain: Architecture at the Time of Liberation,” in African Modernism: The Architecture of Independence; Ghana, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Zambia, ed. Ingrid Schröder, Hans Focketyn, and Julia Jamrozik (Zurich: Park Books, 2015), 5–15.

- 2On the role of architecture in postcolonial Africa, see, for example, Herz et al., African Modernism; Nina Berre, Johan Lagae, and Paul Wenzel Geissler, eds., African Modernism and Its Afterlives (Fishponds, Bristol, UK: Intellect, 2022); Tom Avermaete and Maxime Zaugg, eds., Agadir: Building the Modern Afropolis (Zurich: Park Books, 2022); and Ola Uduku, “West African Modernism and Change,” chap. 8 in Time Frames, ed. Ugo Carughi and Massimo Visone (New York: Routledge, 2017).

- 3Paolo Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan, Costa d’Avorio,” L’Architettura: Cronache e storia, no. 214/215 (August/September, 1973): 186.

- 4Claudio Di Luzio, Rinaldo Olivieri: Architettura come luogo della memoria (Bari: Edizioni Dedalo, 1993), 55.

- 5On the financing of the project, see Ben Soumahoro Mamadou, “Côte d’Ivoire incendie de la Pyramide—Ben Soumahoro accuse . . . et fait l’historique,” Connection Ivoirienne (blog), May 1, 2018, https://connectionivoirienne.net/2015/06/29/cote-divoire-incendie-de-la-pyramide-ben-soumahoro-accusse-et-fait-lhistorique/. On SOCIPEC being “the first entirely Ivorian real estate company with state participation” (my translation), see Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan,” 186.

- 6Rebecca Olivieri, interview by author, February 2023, Verona.

- 7Olivieri, interview by author.

- 8For discussions on La Pyramide as a “large covered market” and its symbolic role in African society, see Bassani, “Centro Comerciale ad Abidjan,” 182, 186–87.

- 9Olivieri’s use of light and space as influenced by Giovanni Battista Piranesi is discussed in Di Luzio, Rinaldo Olivieri, 54. Piranesi was an Italian artist known for his etchings of Rome and, in particular, a series of plates titled Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons).

- 10Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan,” 182–93.

- 11Oliver Wainwright, “The Forgotten Masterpieces of African Modernism,” The Guardian, March 1, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/mar/01/african-modernist-architecture.

- 12“La Côte d’Ivoire en chantier: ouvrages, édifices, équipements . . . – Les 27 projets qui vont tout changer!,” @bidj@n.net, September 22, 2011, https://news.abidjan.net/articles/411345/la-cote-divoire-en-chantier-ouvrages-edifices-equipements-les-27-projets-qui-vont-tout-changer; “The Future Was Born Yesterday,” Street Art United States, May 23, 2023, https://streetartunitedstates.com/the-future-was-born-yesterday/ « La Pyramide d’Abidjan : un trésor brutaliste qui se réveille pour briller à nouveau »,” Sunuculture (blog), October 19, 2023, https://sunuculture.com/2023/10/16/la-pyramide-dabidjan-un-tresor-brutaliste-qui-se-reveille-pour-briller-a-nouveau/

- 13Olivieri, interview by author.

- 14While architectural photography, especially images of the “construction” process, has been very much linked to the birth of modern architecture and the focus on industrial materials such as iron and glass and quick construction techniques (for example, Philip Henry Delamotte’s 1854 photographic documentation of the reconstruction of the Crystal Palace, Progress of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham), it has been primarily viewed as reinforcement or continuation of the architect’s aura, that is, of how their initial designs were realized and materialized. See, for instance, Ian Leith, Delamotte’s Crystal Palace: A Victorian Pleasure Dome Revealed (Swindon, UK: English Heritage, 2005).

- 15Photography has historically served dual roles: On the one hand, it has been a tool of modernity, empowering individuals in postcolonial African settings to shape and express their identities. On the other, it has been used as a means of imperialism, with foreign powers capturing images that sometimes misrepresent or control the narratives of colonized regions. For further reading on these dual aspects of photography, see James Barnor: Stories; Pictures from the Archive (1947–1987), exh. cat. (Paris: Luma Foundation, 2022); Erin Haney, Photography and Africa (London: Reaktion Books, 2010); and John Peffer and Elisabeth L. Cameron, eds., Portraiture & Photography in Africa (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

- 16Isabella Olivieri Lonardi, interview by author, February 2023, Verona.

- 17On Morandi’s contributions to the concrete structure of La Pyramide, see Bassani, “Centro Commerciale ad Abidjan,” 186.

- 18The “field of architectural history” refers to the widely recognized and accepted body of work that historically has been given prominence in the study and teaching of architectural history. It predominantly includes works, theories, and practices that have originated or been celebrated within Western academic and cultural spheres.

- 19Curated by Arthur Drexler, Transformations in Modern Architecture opened at The Museum of Modern Art on February 21, 1979, and ran through April 24, 1979. This exhibit critically explored the evolution and impact of architectural ideas and styles from the 1960s through the late 1970s, highlighting pivotal developments in modern architectural thought and practice. See Arthur Drexler, Transformations in Modern Architecture, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1979). For more on the 1973 article Bassani, “Centro Commerciale Ad Abidjan.”