I believe that painting ultimately still rests on a linguistic level, which enables us to make proper judgments regarding the proficiency and profundity of expression. In other words, what matters to artists is what kind of language they authentically have a feeling for and whether they have entered a desirable linguistic state….Sometimes the feeling for a certain language even triggers the recognition and determination of an idea.1As quoted in Huang Zhuan, “Report From the Artist’s Studio (August 2, 1996),” in Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, ed. Wu Hung (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010), p. 190. —Zhang Xiaogang

Artists in China in the 1980s looked for new visual languages to render reality and their mental states. Many admired modern European artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, and René Magritte. Zhang Xiaogang’s ideas about painting’s linguistic dimension cannot be fully understood without knowing his thoughts on the art of Magritte. Both artists employ strategies such as doubling, displacement, transformation, metamorphosis, and rational visual language that places less importance on technique. However, Zhang’s works amount to far more than successful assimilations of European modernism. We also see in his oeuvre a vernacular style associated with photographic portraits and daily scenes inflected with magic realism. These features demonstrate Zhang’s interest in revisiting histories, depicting trauma, and questioning modes of representation.

post presents here a group of Zhang’s works spanning the late 1980s to the present alongside a selection of paintings by Magritte. These juxtapositions indicate how an artist’s reading of works by “the other” instigates cross-temporal interactions and cross-cultural connections.

In addition, post is publishing a series of primary documents in which Chinese artists give their reflections on Western art. See “related content” at right.

The exhibition Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926–1938 was on view at MoMA from September 28, 2013, to January 12, 2014. See also the exhibition website

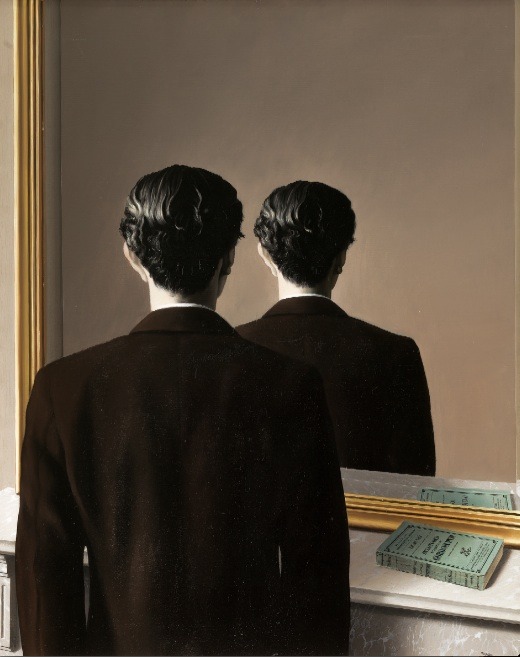

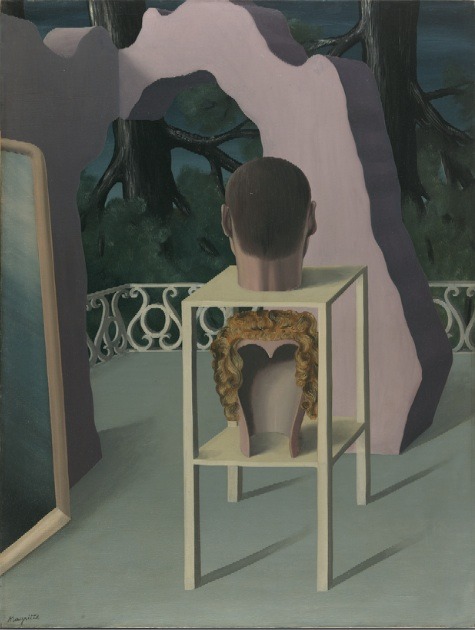

René Magritte. La Reproduction interdite (Not to be Reproduced). 1937. Oil on canvas.

31 7⁄8 x 25 9⁄16″ (81 x 65 cm). Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. © Charly Herscovici – ADAGP – ARS, 2013

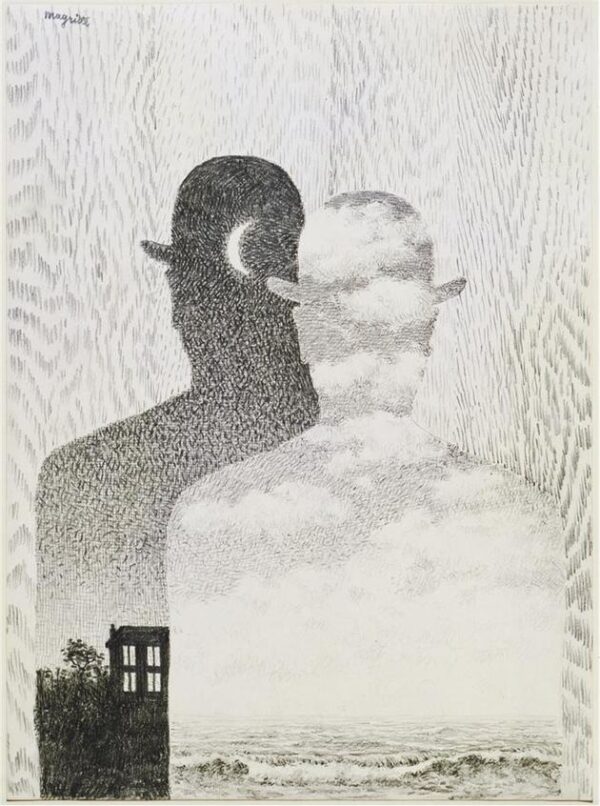

René Magritte. The Thought Which Sees. 1965.

Pencil on Paper. 15 3/4 x 11 3/4″ (40.0 x 29.7 cm). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles B. Benenson. © 2013 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

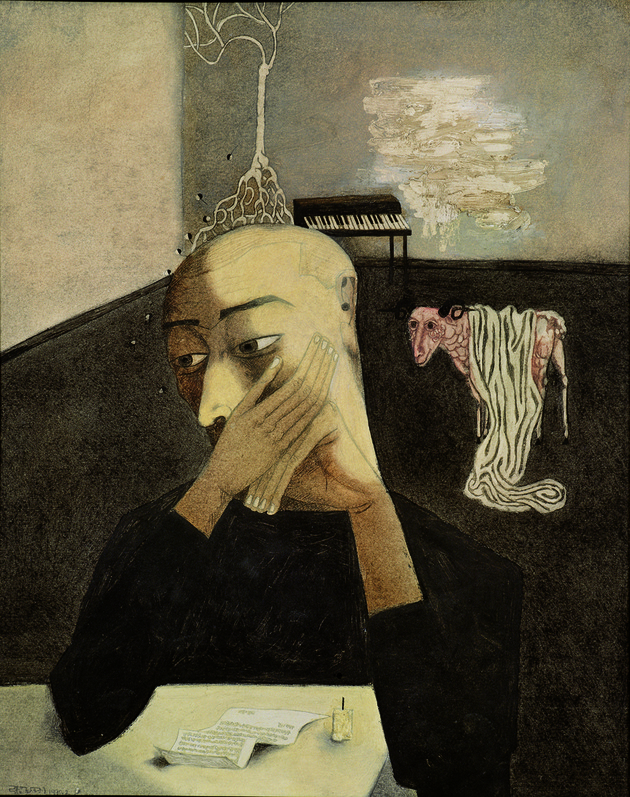

Zhang Xiaogang. Amnesia and Memory: Telephone. 2003. Oil on canvas, 120 x 150 cm. Courtesy of Zhang Xiaogang Art Studio © 2013 the artist

René Magritte. La Durée poignardée (Time Transfixed). 1938. Oil on canvas. 57 7⁄8 x 39″ (147 x 99 cm). The Art Institute of Chicago, Joseph Winterbotham Collection, 1970.426. © Charly Herscovici – ADAGP – ARS, 2013

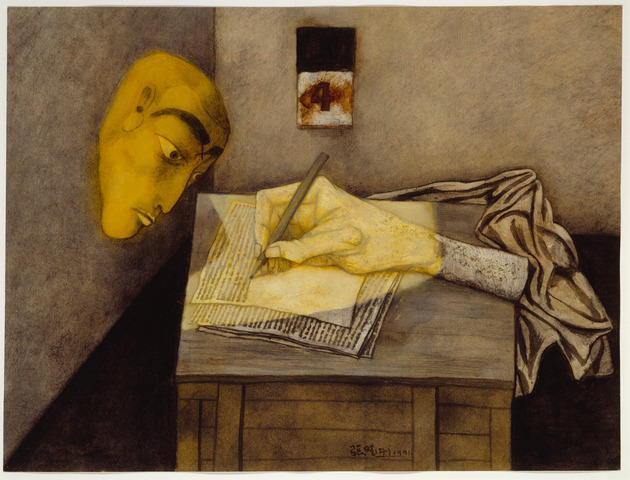

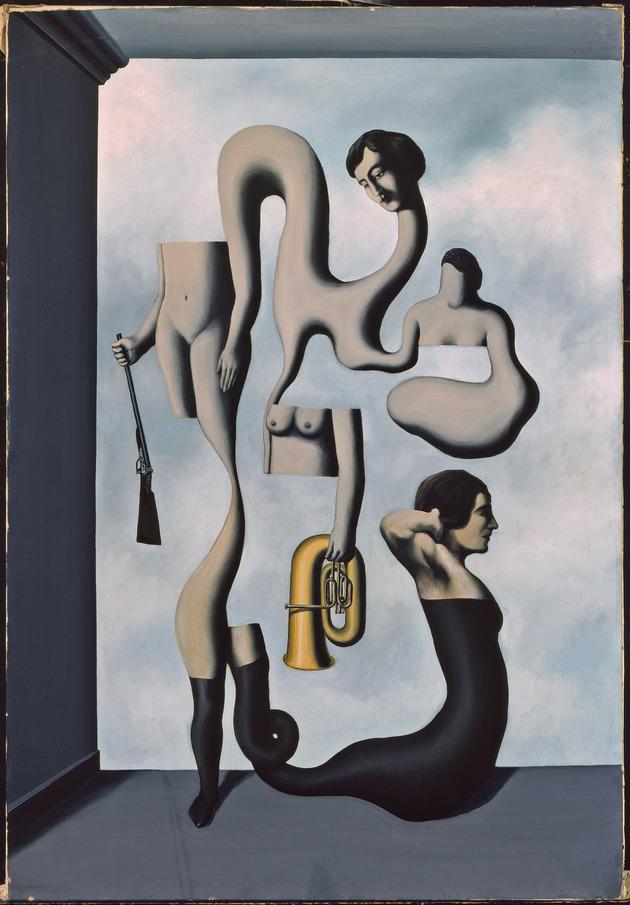

Zhang Xiaogang. The 4th for a Week Private Note. 1991. Oil on paper, 51 x 39 cm. Courtesy of Zhang Xiaogang Art Studio © 2013 the artist

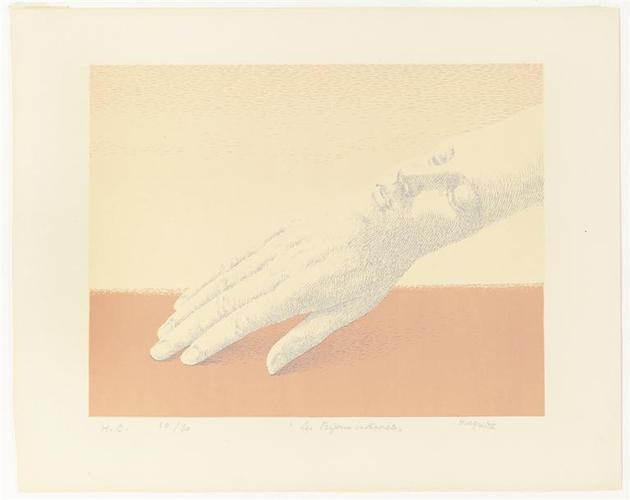

René Magritte. The Indiscreet Jewels (Les bijoux indiscrets). 1963. Lithograph. composition: 9 3/16 x 11 7/8″ (23.4 x 30.2 cm); sheet: 12 5/8 x 15 7/8″ (32 x 40.4 cm). Published by XXe Siècle Éditions, Paris and printed by Mourlot, Paris. Edition: 20 H.C. proofs outside an edition of 75.

Gift of Gilbert E. Kaplan. © 2013 C. Herscovici, Brussels / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

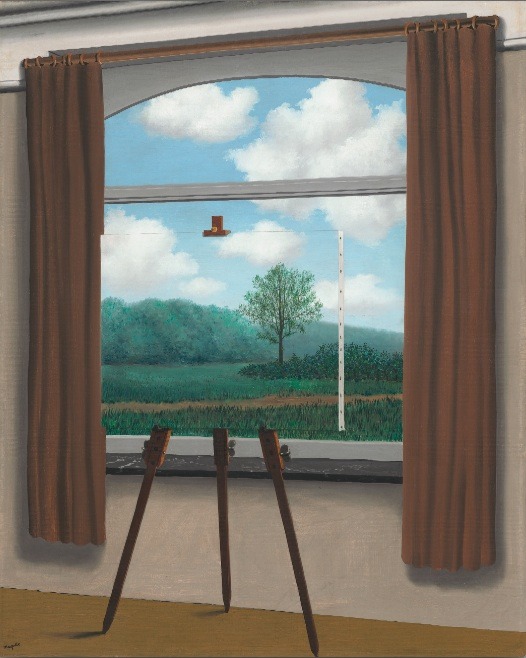

René Magritte. La Condition humaine (The Human Condition). 1933. Oil on canvas. 39 3⁄8 x 31 7⁄8″ (100 x 81 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Gift of the Collector’s Committee 1987.55.1. © Charly Herscovici – ADAGP – ARS, 2013

- 1As quoted in Huang Zhuan, “Report From the Artist’s Studio (August 2, 1996),” in Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents, ed. Wu Hung (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2010), p. 190.