What country is Hong Kong? Hong Kong was an island. Hong Kong will become part of China. MAP Office has decided to present Hong Kong is, with the intention of clearly addressing the specific characteristics of this unique city/territory, which is in a state of perpetual transition. Offering a platform to reveal a hidden urbanity, breaking simultaneously the West’s fascination with the cliché of hyper density, we will outline a provocative exploration of a complex geography/culture/identity. The components of the following series of visual narratives, videos, and interviews, all share a common denominator: Hong Kong is what you cannot see.

In this growing report for post, MAP Office surveys urban developments in Hong Kong. This content was commissioned as part of the research for the 2014 MoMA exhibition Uneven Growth, Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities, curated by Pedro Gadanho (Curator, Architecture and Design).

1. A Space of Disappearance: Hong Kong 1997

The exhibition Uneven Growth, Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities at MoMA gives us the opportunity to imagine a series of critical scenarios for Hong Kong’s future. To consider this possible future we have decided to look back at the history of Hong Kong and read again the seminal book by Ackbar Abbas, Hong Kong, Culture and Politics of Disappearance, sixteen years after its publication.

Abbas’s introduction begins as follows: “Living in interesting times is a dubious advantage, in fact, a curse according to an old Chinese saying. Interesting times are periods of violent transitions and uncertainty. [. . .] The city’s history has always followed an unexpected course—from fishing village to British colony to global city to one of China’s Special Administrative Regions . . .” (p. 1). Time—from whatever present this time is or will be—is a key entry in considering Hong Kong’s current position between the “was” and the “will be.” “A port city that used to be located at the intersection of different spaces, Hong Kong will increasingly be at the intersection of different times and speeds” (p. 4). Considering the complex geography of the territory divided into more than two hundred islands, we can begin to draw more than one intersection and imagine different speeds in this composite archipelago. Some islands play a resistance to time and are frozen in an everlasting limbo; actively disconnected, they are perpetuating pre-colonial and pre-global days. Back in the urban center, Abbas related the energy and vitality of the city to a form of decadence, leading to a frenzy of speculation and consummation of property. The anxiety of Hong Kong citizens described in the book is directly related to a sensation of loss or of never becoming. “Now faced with the uncomfortable possibility of an alien identity about to be imposed on it from China, Hong Kong is experiencing a kind of last-minute collective search for a more definite identity” (p. 4). If we accept Abbas’s thesis, then Hong Kong is still in the process of becoming. If today, the question of Hong Kong versus China is more than ever at the center of all discussions, we can argue that the level of engagement, participation, and resistance to local politic is the new (international) image of Hong Kong.

Source: Abbas, Ackbar, Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997).

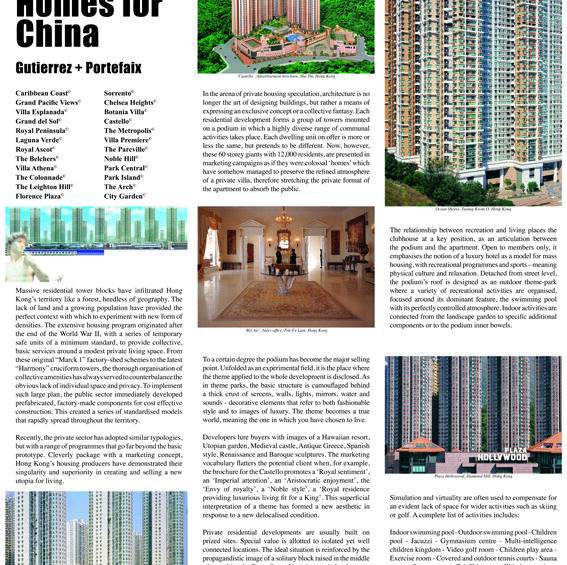

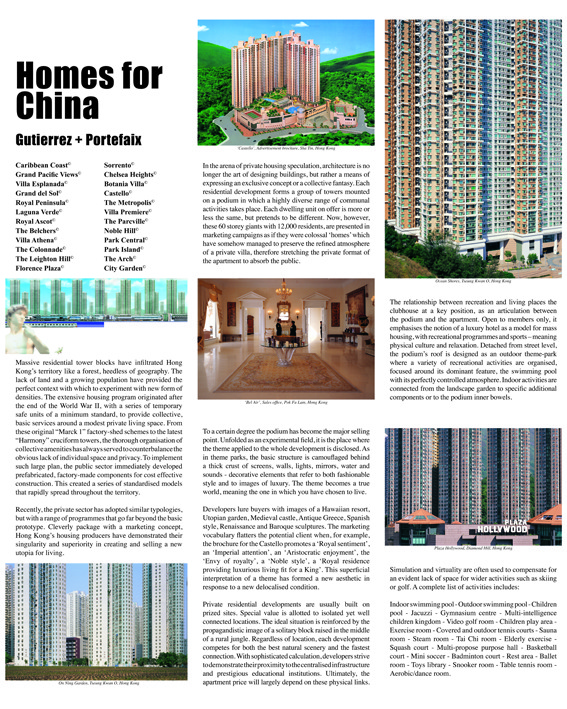

2. Homes for China—Life at hyper density

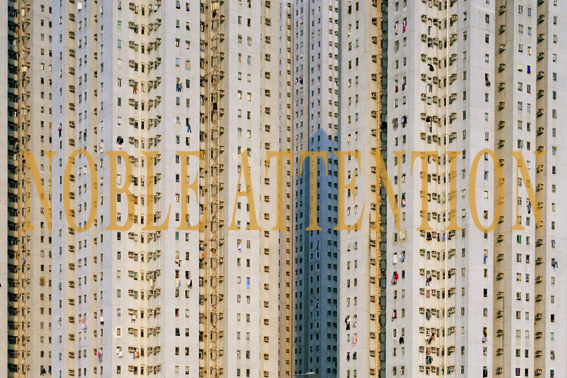

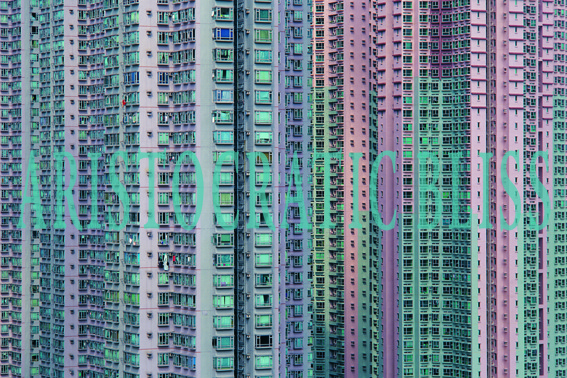

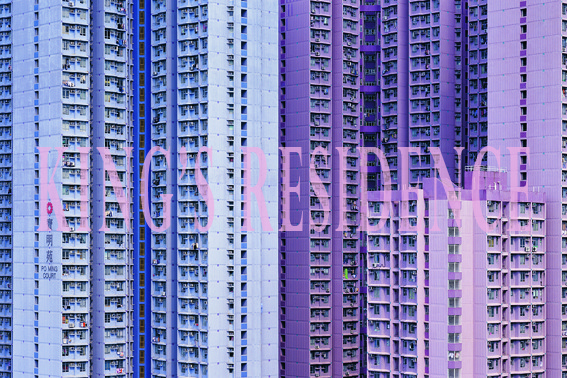

Hong Kong is well-known for its extreme density. Imbricated between mountain and sea, its most characteristic building type is the sixty-four-story residential tower block. Yet it is no longer a typology that is confined to the social housing originally built by the colonial administration desperate not to see the territory sink under waves of refugees arriving from China. Speculation and a hectic market have favored property development and turned these towering giants into housing for the affluent. Leading to a hyper-selective pattern of urban use, Hong Kong housing has been pushed toward ever-higher densities, reaching in its latest incarnation the seventy-two-story apartment tower. With eight flats to a floor, and at least four people to a flat, this makes just one of these developments home to at least twelve thousand people. With a typical site area of between two and three hectares, it calculates into a density of up to six thousand people per hectare. Compared to the comfortable 250 people per hectare in Paris and 500 people per hectare in Singapore, it is twice as dense as the more traditional parts of the urban territory. Hong Kong’s housing program is derived from a highly competitive context, and its planning directly reflects the fickle demands of the market. Cleverly packaged with a marketing concept, architecture is no longer the art of designing a building; rather it provides a means to support the expression of a collective fantasy. Each residential development forms a group of towers mounted on a podium where a highly diverse range of functional activities takes place. These complexes are developed along a unique structure that is repetitive, complete, closed, hermetic, autonomous, and perfectly coded. The residential dwelling unit or cell on offer is more or less the same, but it pretends to be different. To a certain degree, the podium becomes the major selling point and experimental field. It is presented as a colossal house but with the preserved atmosphere of a private villa, thus stretching the private format of the apartment to absorb the public. Massive residential tower blocks have infiltrated Hong Kong’s territory like a forest, heedless of geography. A look at the map, or the view from the mountain peaks, reveals a violent contrast between the dense high-rise developments and the natural island/mountain setting. From this evident juxtaposition, there is no doubt that lack of land and growing populations have provided the perfect incentive to experiment with new forms of densities.

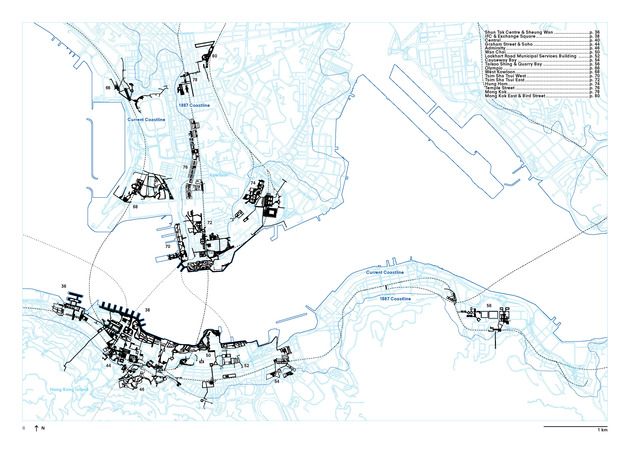

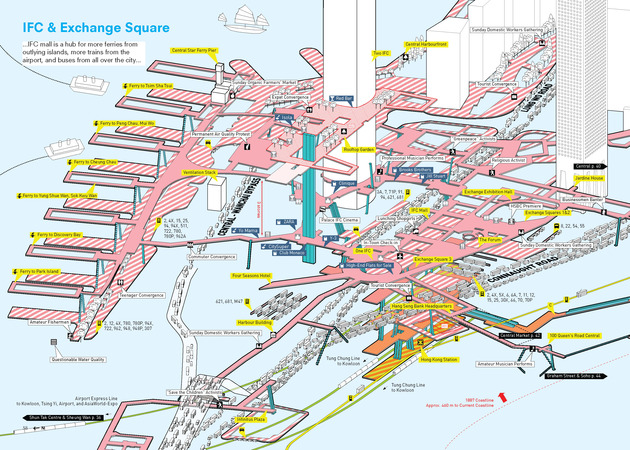

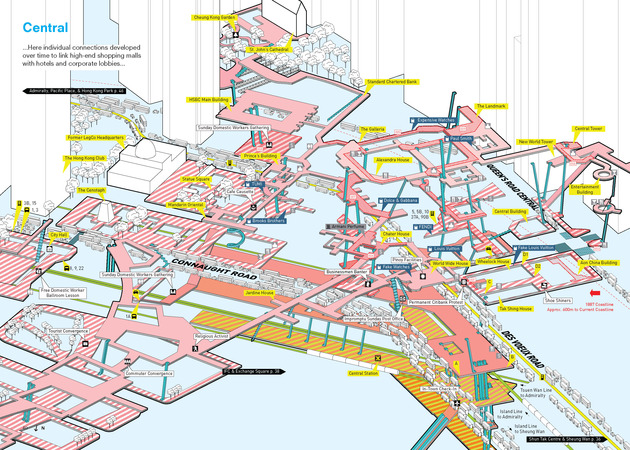

3. Cities without Ground

Hong Kong’s pedestrian infrastructure is key to the efficiency of the territory. Detached from the street traffic, the floating pedestrian network takes the form of either pedestrian bridges or a labyrinth of corridors inside of buildings. Whether outside or inside, in the open air or part of an air-conditioned circuit, pedestrians are able to experience a new game—navigating the urban complexity. Before, men used to explore new lands; now, the adventure is in re-creating a world in response to new living conditions. Dynamic labyrinth is not a sensational experiment, but instead results from the universal notion of an active relationship between people and their environment, whatever form it takes. Everybody enjoys moving from one place to another with the possibility of discovering new shops and facilities. Spatial mobility and continuous human migration create a kaleidoscopic motion, making these artificial lands a prime functional space between the apartment and the urban territory.

Dating from the 1960s, many of these elevated bridges are now much older than the buildings they connect. Analyzing historical maps of Central from the last fifty years shows that the pedestrian walkway network represents the only stable element of the system. As opposed to the buildings that surround it, access to the bridge network has been left unchanged. Renamed “Floating Way” by Japanese researchers,1Space Design, no. 330 (March 1992). the elevated pedestrian network constitutes the vertical expansion of Central’s overcrowded environment. It provides an alternative route that is distinct from the route at ground level. In effect, the complete network allows a safe and quick circuit devoid of vehicle circulation and stops at road intersections.

Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, and Clara Wong, a group of academics and architects, challenged the first cartographic mapping of this unique urban condition to reveal the invisible network and its connections. Recently published as a book, Cities without Ground,2Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, and Clara Wong, Cities without Ground: A Hong Kong Guide Book (Hong Kong: ORO Editions, 2012). a compilation of maps of more than thirty strategic areas, demonstrates the impossibility of planning such a web of intricate connections. As the authors write, this web is “a result of a combination of top-down planning and bottom-up solutions, a unique collaboration between pragmatic thinking and comprehensive master planning.”

4. Near and Elsewhere: An Intersection of Different Speeds and Times

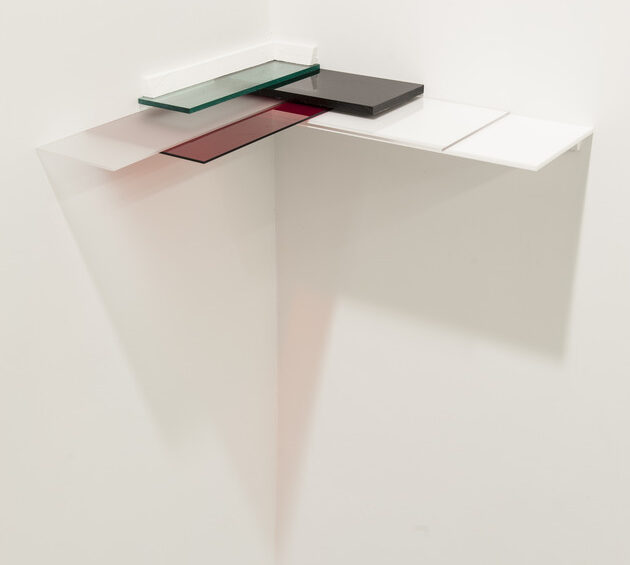

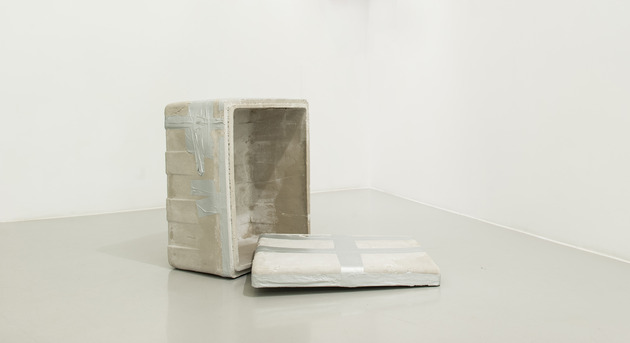

Hong Kong visual culture transcends the urban density with intense flow of information celebrating the capitalist forces driving its commercial areas. Open to speculation, the urban infrastructure multiplies effects to the point of non-legibility. For many years, these questions of visuality and perception have been the subject of the work of Hong Kong–based Portuguese artist João Vasco Paiva. In his latest exhibition Near and Elsewhere, he appropriates various surfaces, textures, and objects to reveal another form of precarious visual presence.

MAP Office: This exhibition comes from a series of explorations of Hong Kong that you orchestrated over the course of many years. How do you select or collect these various elements?

JVP: At first I choose a place, usually a neglected place, one that is marginal, with less pedestrian traffic, where I feel comfortable—a place that somehow translates my positioning within Hong Kong’s local narrative. The selection comes through a process of finding objects that carry aspects that reflect the literal qualities of this place, like the density, the excessive consumption, or the excessive signage. Those objects are a culmination of several activities undertaken by the common citizen. Hence, whereas in my previous exhibition there was a focus on transitional places, in this latest body of work I turned my attention to areas of commerce and their vicinities. But instead of focusing on the core of these areas, I intuitively ended up looking to the sides, to the limits and corners of these places, perhaps because I was looking for something more authentic—something that was not designed to be noticed or seen. The selection of individual objects follows certain parameters that I automatically look for, especially the ability of the objects to encrypt human action; to display usage, erosion, and destruction; and to reveal formal qualities that could not have come about on purpose.

MAP: If you consider each entity as a visual element, as a collective in this show, how do they form relations and dialogue?

JVP: All these works have, as a starting point, elements that were added by the citizen to the urban landscape. The raw material of each work is always an object, or a group of objects that present algorithmic aspects that can introduce the idea of a codified system. There is also a common production process in all these objects—they are mostly created collectively by several individuals who are not aware of their role as contributors to the creation of something that has intricate aesthetic qualities. I highlight these by stopping/freezing that process, and by changing several qualities of these objects (form, materiality, color, or positioning). The scores embedded on each work translate acts of daily labor, compositional decisions that were made in order to organize these elements to occupy as little space as possible according to a number of invisible borders that exist in the city—the sidewalks to where the lumberyard worker extends his workshop (Lumberyard Arrays), the closed shop facade where posters are glued (A Brief Moment in Time), or the advertising storefront where remains of acrylic sheets are discarded (Translucent Debris).

MAP: The video Threshold is edited in slow motion, not only removing any reference to advertising but also opening a moment of hollowness—like a vacuum in the busiest commercial districts of Hong Kong. The city becomes, then, your canvas at a very large scale. How do you see yourself developing in this extended territory you start to define?

JVP: In Threshold, the erasure of written language as well as the pace engineer an intent to map the random arrangements that the outdoors in Hong Kong create in relation to each other—at a micro level in small alleyways, and at a macro level in the way they fill the skyline. The drive gives the notion of a floating perspective point, the contemplative perspective of a “ghost” redesigning the urban scape by maneuvering in confined outdoor spaces. I would say that these past years in Hong Kong and the methods that I have been employing here, led me to define not a territory but rather an approach. This approach passes through experiential research. In order to search for objects that translate time and human action and, therefore, capture the essence of a place, I tend to go through a phase of spatial exploration that allows me to find layers of information that, besides being intrinsic qualities of that place and culture, are commonly disregarded in favor of more obvious and already registered ones. My main focus is on the formal aspects of these objects and places and how they can contribute to aesthetic discourse; as a result, all the contextual factors that the work carries are kept intact and culminate in the formal qualities of the work.

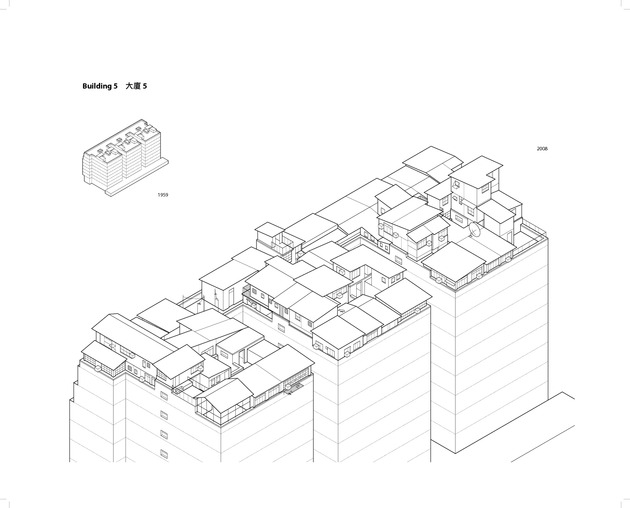

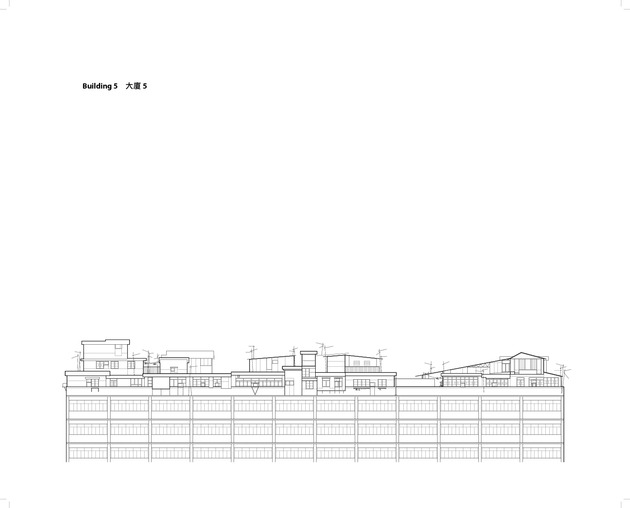

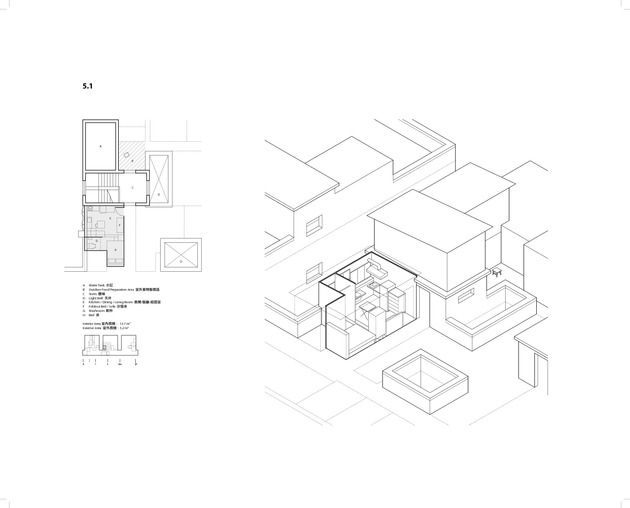

5. Rooftops—a new ground viewed from above

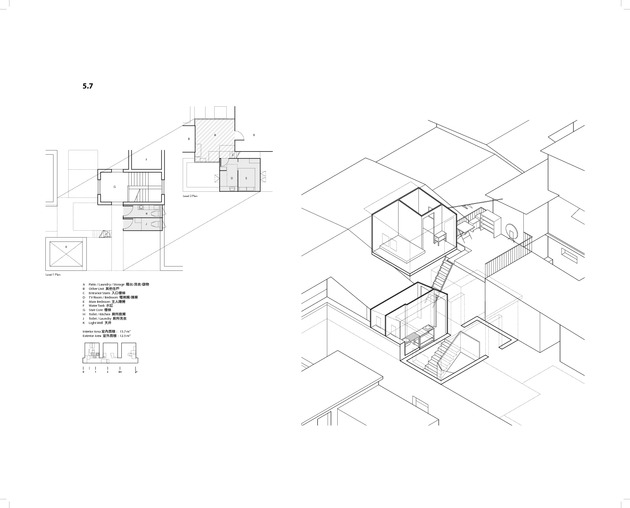

Portraits from Above: Hong Kong’s Informal Rooftop Communities presents a rare survey combining texts, photographs, and architectural axonometric drawings by Stefan Canham and Rufina Wu. Including interior details and interviews with the various occupants, it portrays economy of living as a strategy for the underprivileged community to make a home in the dense city.

In Hong Kong this type of informal urbanism is not only limited to rooftops. Massive flows of migrants escaping China in the 1950s and 1960s established first settlements in the hills of Kowloon and on the outskirts of Kai Tak airport. What we could call shantytowns were made of cheap materials, often salvaged from demolition sites. In this unusual situation, each house offered the minimum space necessary for everyday life. Furthermore, each extension or layer to the original structure was built on top of its parent, hence preserving its history like the pages of a book. As the public housing scheme rapidly targeted those unstable structures (especially after the massive fire in Shep Kip Mei in 1953), rooftop living remained a rare alternative or escape from the expensive real estate market, while one waited for a place in government housing.

According to Dr. Ernest Chui, “In order to decrease pressure on the public housing market, local authorities came up with eligibility criteria like a seven-year residency requirement and a means test. These kinds of exclusionary social regulations have led to alternative forms of housing, such as rooftop dwellings for the people who are not yet eligible for public rental housing, and who are unable to afford better private accommodation.”3Rufina Wu and Stefan Canham, Portraits from Above: Hong Kong’s Informal Rooftop Communities (Berlin: Peperoni Books, 2009) with an essay by Dr. Ernest Chui. Though rooftop housing originally served as a temporary buffer zone, it has since grown to be a fundamental part of the building works. Invisible from the street, it has provided a new ground from where to start alternative construction—in the form of small shanty houses, gardens, and common spaces. These self-built settlements contrast with the perfect, standard facades of adjacent skyscrapers. Yet they also bring a human dimension to the spatial occupation of the city. As houses link to one another across buildings, they form a village in which similar values and principles are shared for a few years.

6. Stag — An Appropriation of Public Space

Stag is a small object designed to be a combination of stool and bag; it invites the public to appropriate fragments of the city, transforming these pieces for a moment. Starting from this principle, it was developed as a tool by Geraldine Borio and Caroline Wuthrich, two Swiss Architects and founders of Parallel Lab, to explore different scenarios of occupation within various public contexts.

Hong Kong is an overexposed “supermarket” where street trade has been a feature of life for more than a hundred years. This frenetic rhythm of consumption is fulfilled by the nonstop flow of people transiting daily from home to work. In this context, public space is an amenity that exists beyond commercial activities. It frequently exists between two buildings or two streets, but it is definitely outside the bounds of speculation. Viewed from above, public spaces appear as series of “holes” that cut the density, yet from the street they are almost invisible—unless one ventures into the narrow paths between the blocks.

Paradoxically, the first event, which took place in Kowloon Park, a conventional public place, was rapidly stopped by the authorities. The “do not . . . ” billboards found at the entrance to every public park include the interdict against sitting on any device that is not provided by Hong Kong officials. Responding to this failure of the system, Parallel Lab strategically conducted “experiments” in different back alleys of the dense city. The series of happenings included a tea ceremony, a screening of the film Little Cheung by Fruit Chan, and a music performance by DJ Wendy Wenn. Each one challenged the production process: organizers sought out free electricity and water, as well as organized publicity, coordinated with neighborhood leaders, etc. In many ways, they succeeded in establishing temporal affiliations with local communities, whose citizens served not only as spectators but also as actors crucial to the process and design of the events taking place. In contrast to the colorful streets with their floodlit facades, back alleys offer a dark territory where happenings can generously offer a new temporal density, one in which the limited public space is always occupied by one guerrilla-type event or another.

7. Hong Kong by Accident

Landscape is a key issue in the making of Hong Kong. With little constructible ground, slopes are part of a vast program of solidification, greening, and landscape treatment. An assistant professor at the Hong Kong University, Adam Bobbette is researching the relationship between landscape and the politics of making ground.

Introduction by MAP Office

Hong Kong by Accident

By Adam Bobbette

Hong Kong is unstable—from the ground up. The geologist William Skertchly, one of the first to write an account of the archipelago in 1893, describes the presence of granite, which makes up most of its geology and can be found in a deposit that stretches as far north as Mongolia. He even suggests that Victoria (the old name for Hong Kong) be called the Granite City because of its prevalence in the ground and architecture. But the granite in Hong Kong is different, Skertchly noticed. It is decomposing. Its vast age and constant pummeling by subtropical rains decompose its architecture from the inside out: “The form of the granite remains, the general structure is untouched, but virtue has gone out of the stone and only a wrecked semblance is left behind.”4Sydney B. J. Skertchly, Our Island—A Naturalist’s Description of Hong Kong (1893), 13. For Skertchly, the archipelago only appears solid.

Skertchly’s anxieties persisted in a myriad of registers up to the period post “handover.” But they always came back to the earth, a slippery, uncertain, and impersonal force. When the rainy season comes, for instance, the land begins to liquefy. This was mostly fine for a while because there weren`t that many people living in Hong Kong into the early twentieth century. But then, the population ballooned with refugees and migrants, and development flattened the mountainous terrain. Now, large masses were placed on unstable slopes. Landslides began to kill annually, en masse. Not only was the place fundamentally temporary but its material base, the ground—that which appeared the most stable—was liquefying.

There emerged, then, a project to solidify the territory. Geotechnical engineers referred to it as “consolidation.” It was. What was most striking, however, was how the process of consolidation that began with the ground traveled through to the political economy of the city. A massive project of knowing the geology of the entire territory was begun. This was followed by a project of pouring concrete over basically any and every slope in the topographically volatile archipelago. This took place throughout the 1980s and coincided with the consolidation of the property market by a very lucky few who would become the tycoons of the region. One such was Li Ka-Shing, who also, at this time, owned one of the two concrete companies in the city, which produced 80 percent of Hong Kong’s annual output. Simultaneously, his company Cheung Kong (Holdings) Limited went from a little more than two and a half million square feet of property in 1974 to ten million by 1979. Likewise, the stabilization of the ground made possible the tower types that would fill up Hong Kong in the next two decades.

………………

James Clavell’s 1981 capitalist dandy depiction of Hong Kong is Nobel House, a book we all know well without needing to read it or to see Pierce Bronson play the taipan (boss man) in the TV miniseries based on it. This is because we already know the story: Hong Kong is a city of free-market competition and a population with an industrious work ethic. Milton Friedman (the free-market evangelist living life large in the noxious gases of the high-Thatcher era) included a visit to the city for an episode of Free to Choose, his short-lived television series from the 1980s. There, he re-capitulates these latter clichés in addition, no less, to appending one other Hong Kong cliché: images of junk boats in the harbor circulating among contemporary speedboats. Clavell, however, does good work in going beyond these in a psychosocial portrait of personal advancement in a perpetually unstable environment. His characters’ lives are fabricated out of the constant maintenance of their social connections in a shaky social world of competition and nepotism. Personal wealth is directly tied to their personal (and familial) connections. They are, in fact, one and the same. The book’s climax is a landslide in a posh neighborhood that takes one high-rise and throws it through another. In the TV version, there was a party of elites in the building. Some live, some don’t. The landslide becomes a kind of sorting mechanism—social Darwinian grafted onto free-market competition, killing off some, allowing others to survive. The characters then enter into a process of re-establishing their social links in view of their personal accumulation as they pull themselves out of the muddy rubble, with dresses slashed and limbs broken. The landslide was modeled on a real one, just a few hundred meters from my university office.

…………….

Land is the political and economic engine of Hong Kong. Or, perhaps, it is more hydraulic. The government owns all land in the territory; individuals don’t. They have access to land via leases: terminal contracts, letters that self-destruct. This comes from the colonial period. This directly affected ownership structures and the way in which the market would play out: the management of land ownership was undertaken primarily by the government and was its primary source of revenue. The government then worked between two poles: the maintenance of a land reserve and the timed release of land into the market. It’s like a liquid. The gates are opened and land is leaked, and then they are closed again in a magical process of market manipulation. The so-called scarcity of land has unquestionably been fabricated by this process since the foundation of the colony.

8. Lee Kit. ‘You.’ And the Realm of the Everyday

‘You.’ is an extension of ‘You (you).’, a solo exhibition by Lee Kit presented in the Hong Kong Pavilion at the 55th International Venice Biennale. Back in Hong Kong, the exhibition is developed in collaboration with landscape architect/artist Sara Wong, who served as spatial concept designer, providing platforms and partitions intertwined with the unique Cattle Depot space (a former location for the slaughter of cattle). The spatial appropriation of a space is one of the key conditions to understanding the complexity of Hong Kong territory. And truly, space and context play major roles in Lee Kit’s work, as the artist often opens the boundaries between public and private spheres, engaging the viewer “you” to be part of his installations.

As artifacts poetically juxtapose traces of previous occupation, the visitor rapidly starts to question what is he/she looking at. With ‘You.’ the Hong Kong heritage building is intruded with often cheap and common found objects, a security guard booth, buckets of various colors, an umbrella, various cloths and plastic mugs, and numerous platforms inviting the audience to pause. Yet the sense of time, values, and memories are curiously embedded with both context and objects. Projected onto walls and small TV monitors, videos open new windows on daily life activities such as cooking, the sounds of utensils clanking, and paper tearing, which interplay with each other.

The first symptom of an appropriation begins with the laying out of familiar and recognizable objects. In that sense, one can say that the recognition of the everyday defines a place called home. The soft cocooning of the commonplace, as opposed to the cold dimension of the white cube gallery, operates by accumulation and repetition of ordinary gestures. The sink lies half a meter away from the shower, and the various clothes hanging from the walls celebrate a talent of concentrated activities. When walking through the installation, surfaces appear bleached and colors are faded to pastel-like tones. Yet, the soft tones are carrying an intimidating meaning through the wording used by the artist. You cannot stay neutral as you participate in the show. ‘You.’ is a readymade often used by Lee Kit in paintings ‘You’ (Pears) (2012), ‘Fuck You.—100g’ (2012), texts that starts with “Dear you:,” and finally ‘Every breath you take’ (2013) in a recent installation in Shanghai at Minsheng Art Museum.

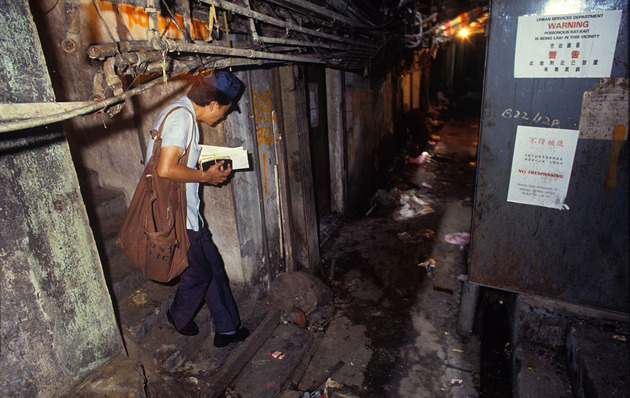

9. Kowloon Walled City

The Kowloon Walled City is a legendary piece of Hong Kong urban architecture whose legacy lives on despite the structure’s demolition in 1993, just a few years before the retrocession. Films, interactive websites, video games, publications, and, earlier this year, the reconstruction of a portion of it as a theme park in Japan, contribute to the public’s enduring fascination with this unique piece of urban architecture.

The singular status of this tiny piece of land, which has remained a Chinese enclave in the Kowloon section of the British colony of Hong Kong, helps to explain the erratic nature of its occupation. The many attempts to clear the former Chinese military base were met with resistance on the part of local and Canton officials. As a result, the site of the Kowloon Walled City developed as a special zone, one which operated outside traditional law enforcement and served as a refuge for different groups of triads (Chinese Mafiosi). Yet the Kowloon Walled City was more than an island for lawbreakers. By the 1980s it had become home to some 50,000 inhabitants, reaching an incredible density of 1,920,000 inhabitants per square kilometer (about 120 times the density of New York today).

The announcement of its demolition prompted a number of photographers, architects, and filmmakers to penetrate the walled city and dissect the hitherto unseen components of the structure in an attempt to come to an understanding of the factors that contributed to its exponential growth. A group of eleven young Japanese architects5Terasawa Hitomi, Daizukan Kyuryuyou (Tokyo, 1997) spent a few weeks exploring the interior of the compound, observing all the details of domestic life and small businesses and examining the infrastructure and the objects found within it in order to reproduce a panoramic illustration of a complete section of the megacity. Singapore- and Hong Kong–based architects Louise Low and Aaron Tan6Louise Low and Aaron Tan, “Kowloon Walled City,” Iceblog: Urbanism, Architecture and Environment used the entropic condition of the buildings to photograph the demolition in a series of slices—as if cutting through a cake. Greg Girard and Ian Lambot7Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, City of Darkness: Life in the Kowloon Walled City (London: Watermark, 1999) spent five years documenting and photographing the countless public and private interiors in order to produce a portrait of the unique community. Confirming the long-lasting fascination with the Kowloon Walled City, they have just published City of Darkness: Revisited8Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, City of Darkness: Revisited (London: Watermark, 2014), a book that consolidates twenty years of research on the topic.

Today a park stands in the place of the walled city, but a number of traces remain of this historic landscape. Remnants of the south gate of the city and the original concrete foundations, along with two Qing dynasty guns and the entrance plaques to the city produce a unique monument to Hong Kong’s most famous piece of architecture.

- 1Space Design, no. 330 (March 1992).

- 2Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, and Clara Wong, Cities without Ground: A Hong Kong Guide Book (Hong Kong: ORO Editions, 2012).

- 3Rufina Wu and Stefan Canham, Portraits from Above: Hong Kong’s Informal Rooftop Communities (Berlin: Peperoni Books, 2009) with an essay by Dr. Ernest Chui.

- 4Sydney B. J. Skertchly, Our Island—A Naturalist’s Description of Hong Kong (1893), 13.

- 5Terasawa Hitomi, Daizukan Kyuryuyou (Tokyo, 1997)

- 6Louise Low and Aaron Tan, “Kowloon Walled City,” Iceblog: Urbanism, Architecture and Environment

- 7Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, City of Darkness: Life in the Kowloon Walled City (London: Watermark, 1999)

- 8Greg Girard and Ian Lambot, City of Darkness: Revisited (London: Watermark, 2014)