Curator Xenia Benivolski looks at the work of Zanis Waldheims (1909–1993), a self-taught Latvian artist who lived in exile in Canada and spent most of his life on a series of about six hundred geometrically abstract drawings. Benivolski considers the thinking behind Waldheims’s work and its meaning in terms of exile, diaspora, and art historical scholarship.

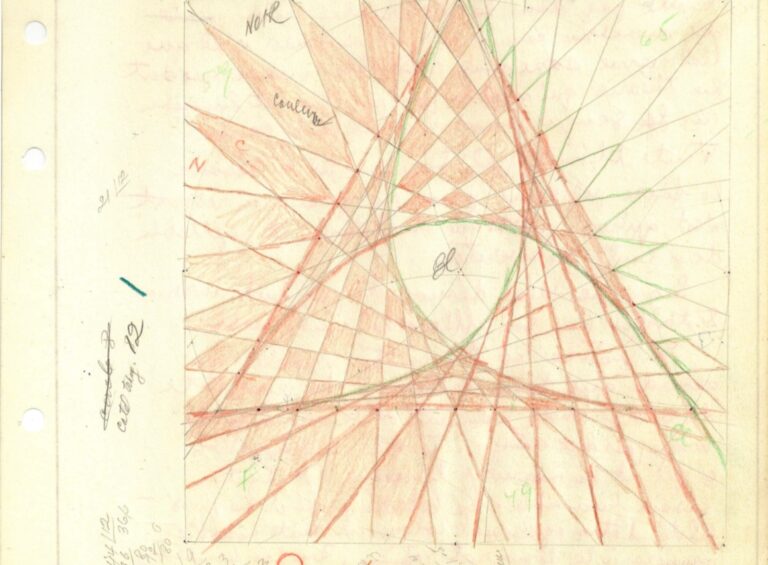

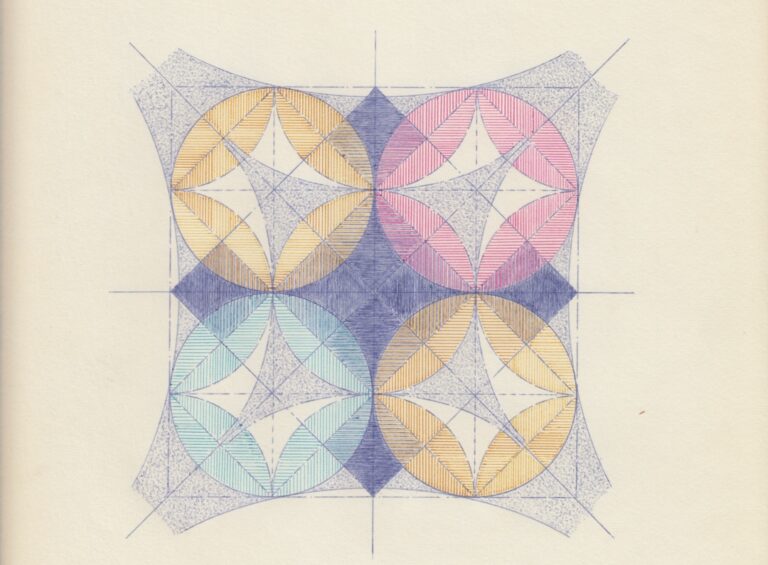

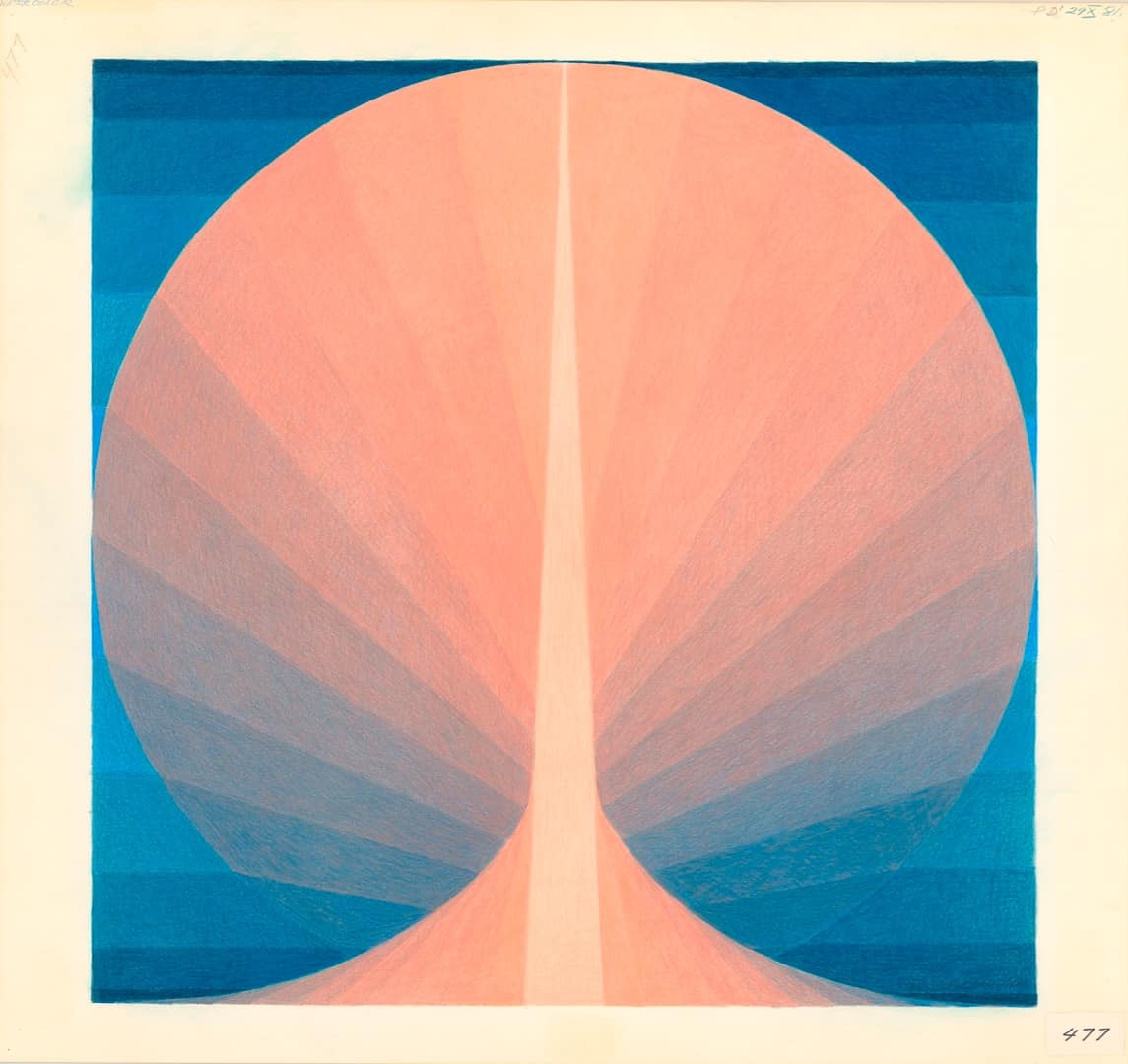

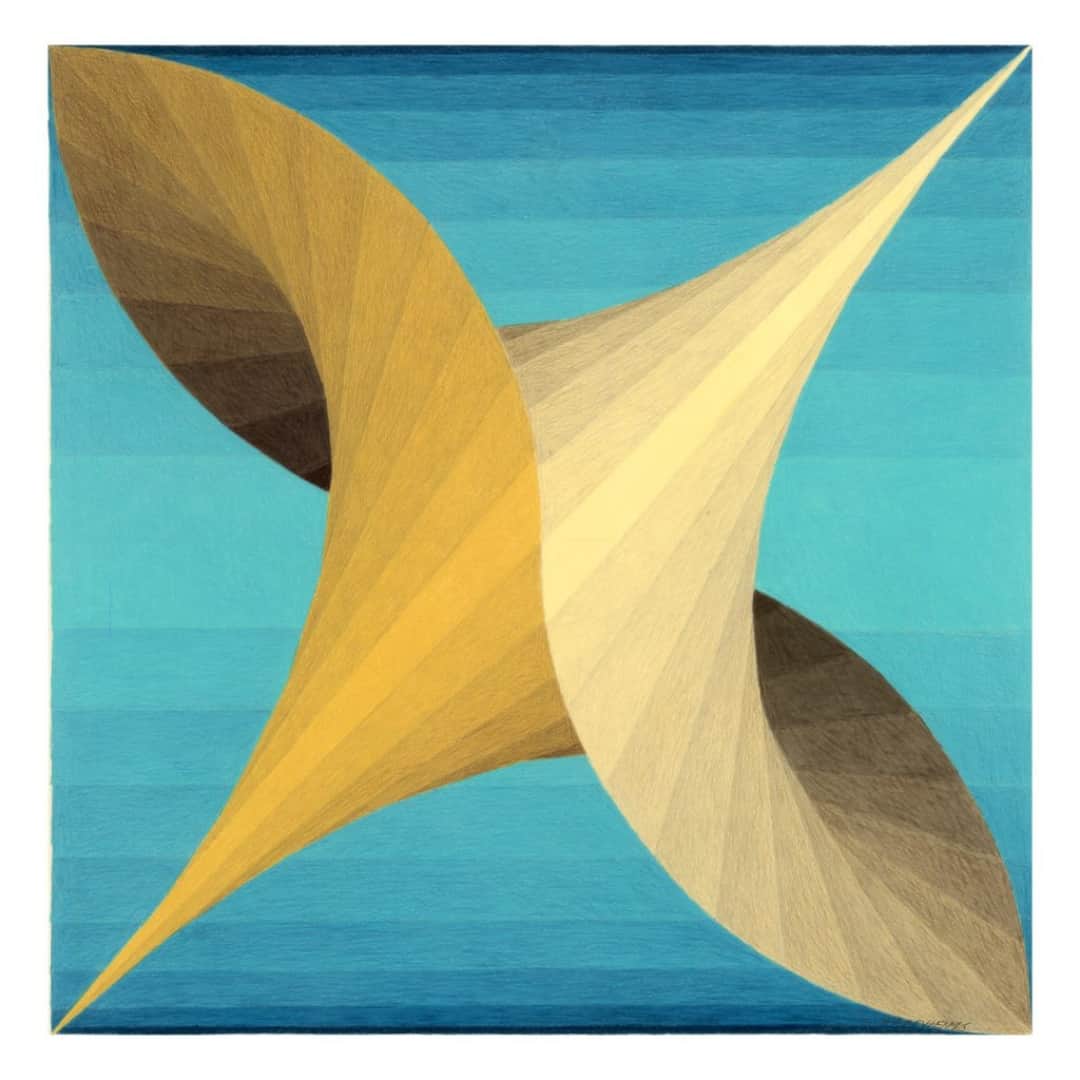

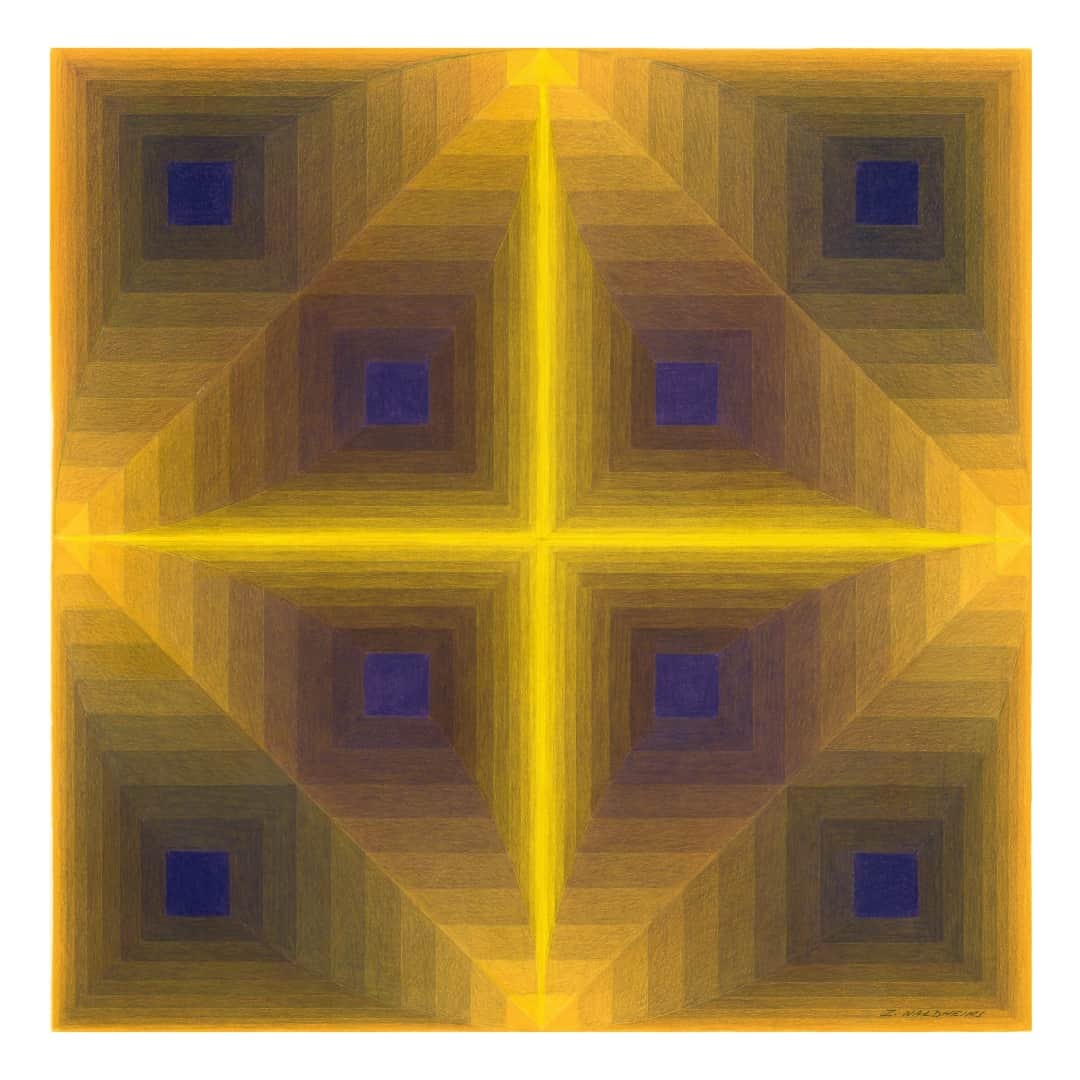

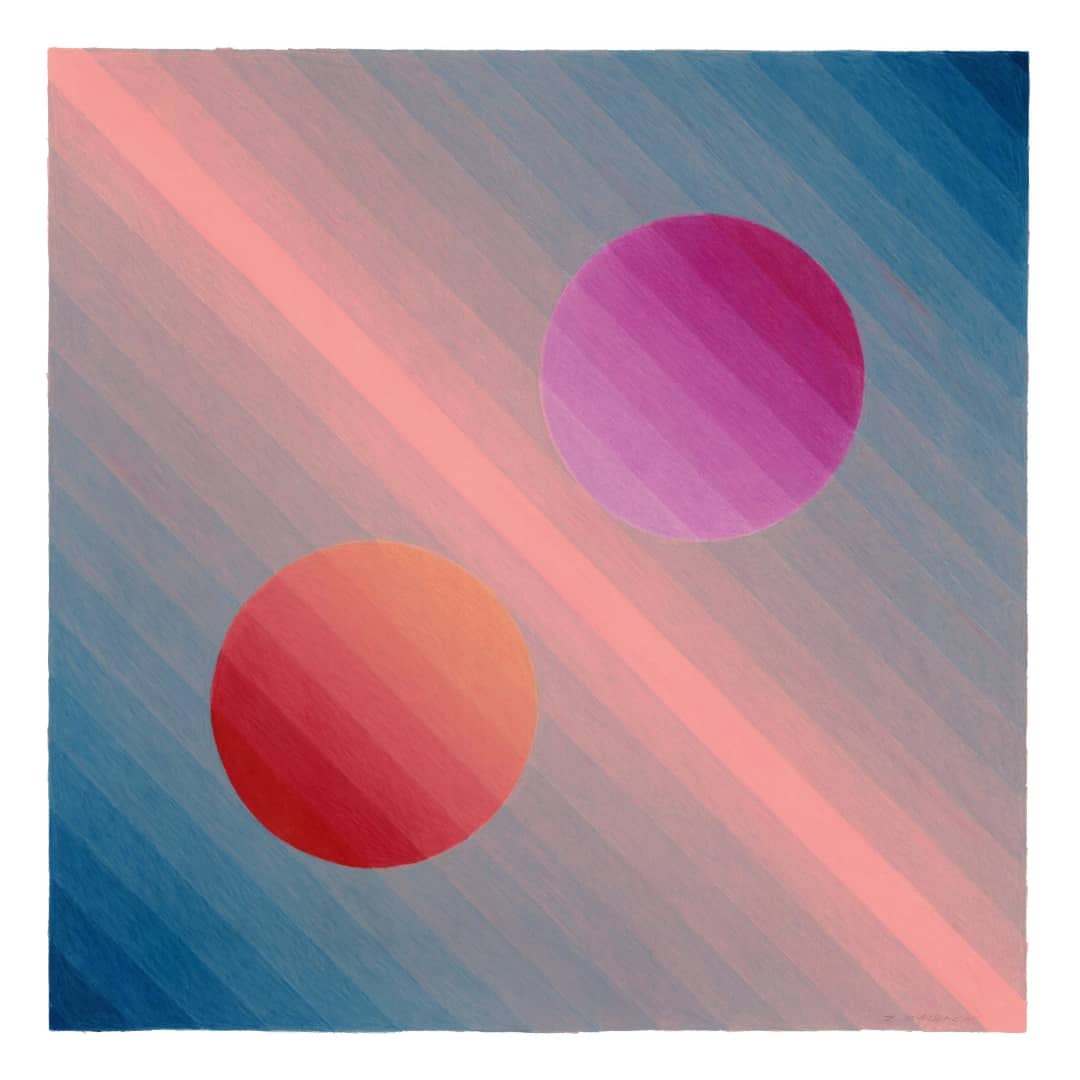

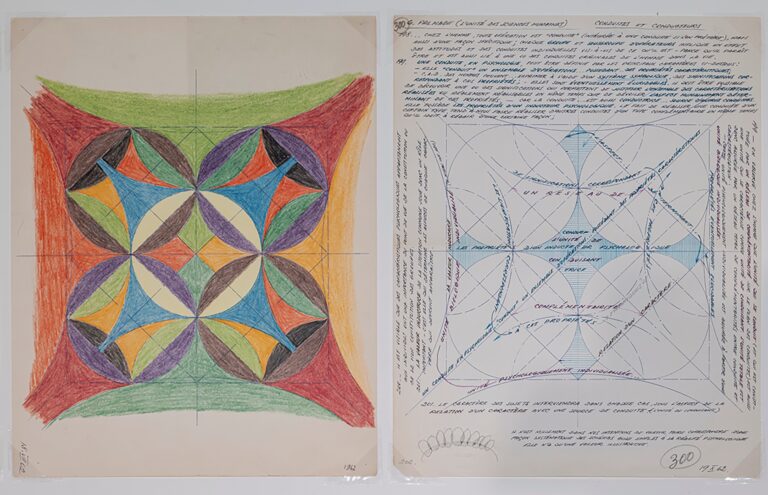

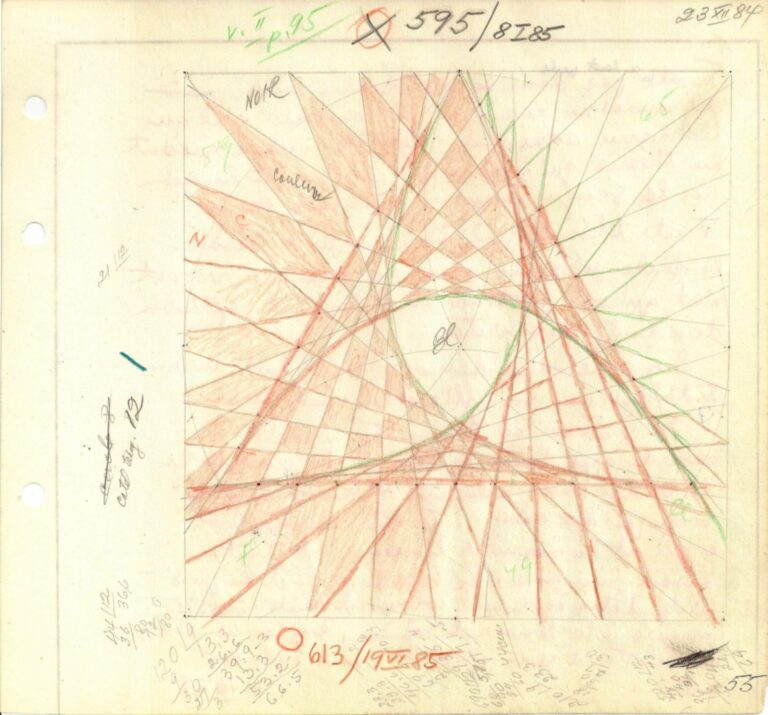

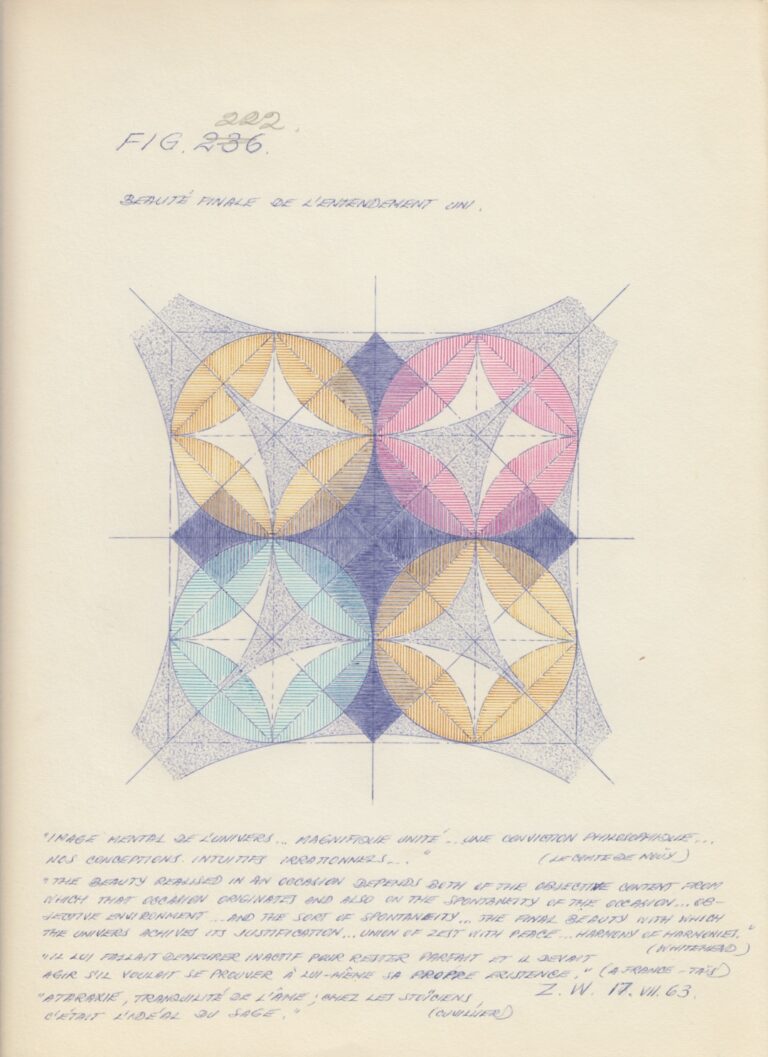

Soviet occupation and Russian imperialism at large have had profound and long-lasting ramifications, particularly for the generations of migrants and immigrants who continue to grapple with piecing together their fragmented identities. Latvian artist Zanis Waldheims’s life and work offer an evocative example of how the experiences of such individuals can provoke a form of expression at once restricted and expansive, tightly controlled and struggling to break free. Working on his thesis for more than forty years, he created a world of philosophical diagrams. In this series of six hundred meticulously rendered pencil drawings consisting of recurring geometric compositions—in his words, “map[s] for human orientation”1Yves Jeanson, recorded interview with author, December 27, 2019. —each line and shade is assigned an existential value. These “values” are explained in the artist’s obsessive annotations, which fill the many sprawling sketchbooks, notebooks, and preparatory drawings in his archive.

An artist who came of age amid World Wars I and II, Waldheims was among those who, in their aftermath, sought to be part of a progressive Western Europe. However, his expectations of inclusion were not met, and as the Soviet regime and influence encroached on his homeland, he mediated his disappointment and feelings of betrayal by reading. Craving access to open intellectual and ideological fields of thought, he was engrossed in exploring the work of Western rational and empirical philosophers, historians, and linguists as oppressive Soviet-backed regimes were tightening their grip in the Baltic sphere. Observing the precision with which the occupiers peddled communist dogma and propaganda, he saw little room for imagination. Waldheims, who was trained as a lawyer, blamed the manipulation of the masses on the fickle, double-sided words of those in power. Soon after leaving Latvia as an exile, he developed a complex visual lexicon that functioned outside of usual significative systems and began to incorporate drawings and diagrams in his texts.2 On Thursday, February 23, 1967, he wrote, “I find that my artworks belongs to a new type of language which is likely to be complementary to verbal logic, which is a rather an imprecise expression which is differently structured in geometric order.” Zanis Waldheims, “Notes 1952–1969.” Private collection of Yves Jeanson. He engaged in writing, which he categorized as “exhaustive thinking,”3Jeanson, recorded interview with author. throughout his life as an immigrant living in Paris and Montreal, where he eventually settled.

Once in Canada, in particular, Waldheims used drawing and diagramming to articulate his philosophical ideas, which he documented extensively through writing, drawing, and journal entries. He drew on the likes of Benedict de Spinoza, Will Durant, Henri Pirenne, and Maine de Biran, conceiving of human consciousness as a multilayered, multifaceted object that could be mapped or otherwise visually articulated. Inspired by Biran’s ideas, he attempted to create a set of images synthesizing different theoretical fields. Conceived as graphs or scientific illustrations, these works show how diverse systems of knowledge relate to one another, the descriptions of the layers and their indexical meanings forming an integral part of his oeuvre. Psychology, phenomenology, mathematics, physics, and linguistics overlap to create an “exhaustive” set of diagrams representing all sciences and humanities as facets of one massive prism. Through drawing, Waldheims grappled with the notion of art-making from the perspective of a self-identified non-artist. In his first set of notebooks, he wrote that “it is art that tries to symbolically represent metaphysical conceptions, as transformed into conceptions of a particular geometrization, able to present the totality of an explicit content on a surface that by constitutive degrees is completely used up.”4Waldheims, “Notes 1952–1969.” Siloed from the formal and professional art context of his contemporaries, Waldheims understood not only his own art practice but also all artwork as potentially scientific work.

To this day, some of the world’s foremost art institutions remain consumed with the task of filling the critical gaps created by authoritarian regimes in Europe. Art history is constructed on this momentum. The question that arises in response to Waldheims’s work is not whether he was a pioneer in his field of geometric abstraction—he certainly was not—but rather how it is that, somewhere, this particularly stylized mode of expression was adapted by a person who had no interest in its previous iterations. Waldheims did not imagine himself to be part of the abstract art movement nor did he see himself as a player in the grand scheme of art history. This is perhaps due to the fact that in his time, little information on fringe groups affected by world events was available. The microhistories5 Carlo Ginzburg, John Tedeschi, and Anne C. Tedeschi, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It,” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 1 (Autumn 1993): 10–35. now surfacing offer more potent ways of looking at the canon, which was shaped by the same colonial forces that shaped the political world.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Soviet regime imposed stringent restrictions on the expression of ideas perceived as radical, a shift significantly impacting contemporary artistic practices. As a result, metaphor emerged as a crucial instrument for communicating simple political truths; for example, Soviet fiction produced during this period is known for the double entendres embedded within it. It was during this time that Waldheims, who was by now living in Montreal, developed a keen understanding of the role of language in constructing truths. As he noted in 1969: “All verbal ‘truths’ are merely the truths of degrees of a totality. It is only the drawing that can convey the simultaneous meaning of the truths of a totality. Thus, once again, we must draw more and write less!”6Waldheims, “Notes 1952–1969.”

Vexed and frustrated by the ambiguous and playful linguistic elements that could lend themselves to poetic interpretation in art, Waldheims was particularly critical of the subjective nature of figurative and history painting, which he saw as stunted methodologies of self-expression. Alluding to his own inability to come to terms with either language or image, he frequently compared himself to Spinoza as excused by Durant: “Writing in Latin, he [Spinoza] was compelled to express his essentially modern thought in medieval and scholastic terms; there was no other language of philosophy which would then have been understood . . . [for example] objectively for subjectivity, and formality for objectively.”7Will Durant, “The Ethics,” in Story of Philosophy, 2nd ed. (1926; New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 169. Compelled to express his point of view with the limited means available to him, Waldheims decided that “since human actions obey laws as fixed as those of geometry, [the field of ] psychology should be studied in geometrical form, and with mathematical objectivity. I will write about human beings as though I were concerned with lines and planes and solids.”8After Benedictus de Spinoza, who announced, “I shall consider human actions and desires in exactly the same manner, as though I were concerned with lines, planes, and solids.” Spinoza, “On the Origin and Nature of Emotions,” in The Chief Works of Benedict de Spinoza, vol. 2, De Intellectus Emendatione—Ethica. (Select Letters.), rev. ed. (London: George Bell, 1891), 129.

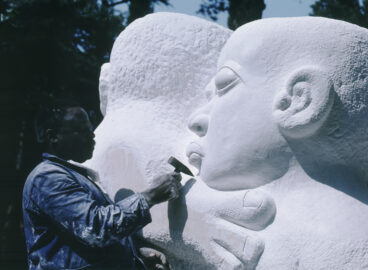

Informed by his own life experiences and political trauma, Waldheims saw parallels where there were none, and he borrowed from various philosophical methodologies to construct a collage that suited his unique perspective. Paradoxically, his creations are far more interesting to art historians than to mathematicians. Despite this fact, he had few opportunities to exhibit them. In his lifetime, Waldheims showed some works in Quebec, in the local school and library in Lachine in 1976, as well as at the regional museum of Lachine shortly before he died. Posthumously, his works have been researched and exhibited by curator Inga Lāce at the Festival SURVIVAL KIT 8 organized in 2016 by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art in Riga;9See “Festival SURVIVAL KIT 8,” Latvian Centre for Contemporary art website, https://lcca.lv/en/exhibitions/festival-survival-kit-8/. at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga in 2018 as part of an exhibition focusing on Latvian artists in exile and the theme of migration;10See “PORTABLE LANDSCAPES. Comprehensive Latvian Exile and Emigrant Contemporary Art Project,” Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art website, https://lcca.lv/en/events/parnesajamas-ainavas–br-latvijas-trimdas-un-emigracijas-laikmetigas-makslas-izstazu-cikls/. at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto in 2021 in combination with ephemera from his archive;11See The Exhaustive Thought, exhibition curated by Xenia Benivolski, Art Museum at the University of Toronto website, https://artmuseum.utoronto.ca/exhibition/zanis-waldheims-the-exhaustive-thought/. and at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź in 2021 in dialogue with the work of other artists engaged in nonfigurative forms of expression.12See “Riga Notebook. Following the Line of Wacław Szpakowski,” Muzeum Sztuki website, https://msl.org.pl/riga-notebook-following-the-lines-of-waclaw-szpakowski/. Until their inclusion in these exhibitions, his drawings were mostly kept by his longtime friend Yves Jeanson or otherwise found in the National Archive of Latvia—as opposed to in an art museum. But now, they have entered the collections of the Latvian National Museum of Art and the Muzeum Sztuki, where they are more accessible to art researchers.

The compendium of sketches, drawings, and notes within these collections is accompanied by a veritable library of philosophical and theoretical texts, mostly of French origin, that are marked up with marginalia. In these annotations, Waldheims forges connections between his theoretical drawings and the words or concepts in the books he was reading, providing unique insights into his creative process. His own texts are replete with small symbols that serve as shorthand to evaluate the conceptual balance of the main text. These gestures, which he borrowed from the written vocabulary of psychologist and anthropologist Joseph Campbell, are meant to draw attention to elements of the text that he found relevant to the use of geometry in his drawings while also punctuating the tempo of the writing. By redirecting the texts, both his own and that of others, Waldheims injected the particular works with a sense of paranoia and delusion, as well as with a strong desire for cohesive systems. However, the musings and connections between the drawings, texts, colors, and shapes are anything but universal, for they are but one man’s attempt to connect the dots—an endless and almost obsessive pursuit. Waldheims numbered and renumbered his drawings, seemingly forever unsettled regarding the correct order of things. Indeed, he appears to have been unsure of whether freedom precedes art or whether nature, liberty, and community are on equal footing. Causality, if it exists at all, is not overbearing; to be sure, Waldheims believed that everything is connected. He was lost in space because he was lost in time, and yet through his relentless attempts to map his whereabouts, he managed to create the conditions for his own universe.

Waldheims, like many post-Soviet migrants, was unable to return to his homeland or to reunite with his family. As an artist in exile, he found solace in his artistic creations, which served as means of expression of his inner world. Edward Said has aptly described the exiled as individuals who strive to rebuild their shattered lives, to create new worlds that are both a compensation for their losses and a testament to their resilience. However, as Said notes, the exile’s new world is often unreal, in effect resembling a work of fiction.13Edward W. Said, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000). 61–62. Just the same, the exiled artist proves that new worlds can be created, that they can emerge from the interstices between languages and cultures, and the fissures between rational and irrational systems of inclusion and exclusion. Fiction provides a window into a different reality, a world in which the boundaries between the real and the imagined blur, and where alternative forms of expression and meaning-making can flourish.

- 1Yves Jeanson, recorded interview with author, December 27, 2019.

- 2On Thursday, February 23, 1967, he wrote, “I find that my artworks belongs to a new type of language which is likely to be complementary to verbal logic, which is a rather an imprecise expression which is differently structured in geometric order.” Zanis Waldheims, “Notes 1952–1969.” Private collection of Yves Jeanson.

- 3Jeanson, recorded interview with author.

- 4Waldheims, “Notes 1952–1969.”

- 5Carlo Ginzburg, John Tedeschi, and Anne C. Tedeschi, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know about It,” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 1 (Autumn 1993): 10–35.

- 6Waldheims, “Notes 1952–1969.”

- 7Will Durant, “The Ethics,” in Story of Philosophy, 2nd ed. (1926; New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012), 169.

- 8After Benedictus de Spinoza, who announced, “I shall consider human actions and desires in exactly the same manner, as though I were concerned with lines, planes, and solids.” Spinoza, “On the Origin and Nature of Emotions,” in The Chief Works of Benedict de Spinoza, vol. 2, De Intellectus Emendatione—Ethica. (Select Letters.), rev. ed. (London: George Bell, 1891), 129.

- 9See “Festival SURVIVAL KIT 8,” Latvian Centre for Contemporary art website, https://lcca.lv/en/exhibitions/festival-survival-kit-8/.

- 10See “PORTABLE LANDSCAPES. Comprehensive Latvian Exile and Emigrant Contemporary Art Project,” Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art website, https://lcca.lv/en/events/parnesajamas-ainavas–br-latvijas-trimdas-un-emigracijas-laikmetigas-makslas-izstazu-cikls/.

- 11See The Exhaustive Thought, exhibition curated by Xenia Benivolski, Art Museum at the University of Toronto website, https://artmuseum.utoronto.ca/exhibition/zanis-waldheims-the-exhaustive-thought/.

- 12See “Riga Notebook. Following the Line of Wacław Szpakowski,” Muzeum Sztuki website, https://msl.org.pl/riga-notebook-following-the-lines-of-waclaw-szpakowski/.

- 13Edward W. Said, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000). 61–62.