As the Guggenheim prepared to open its exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World on October 6, 2017, post collaborated with the Guggenheim’s Checklist blog to reflect on works by two important contemporary artists from China. Both Yang Fudong and Zhang Peili are known for their video works. In the exhibition (and in MoMA’s collection) is Zhang’s Document on Hygiene No. 3 (1991), which Guggenheim curator X Zhu-Nowell discusses in this essay. On loan from MoMA, Yang’s An Estranged Paradise (1997–2002) is featured in the exhibition and is the subject of the following essay by MoMA curator La Frances Hui.

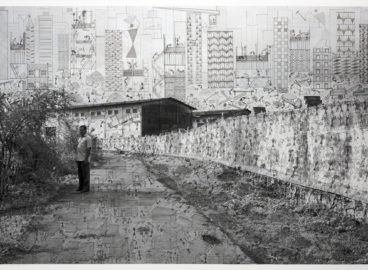

Yang Fudong (Chinese, born 1971) has called An Estranged Paradise (1997–2002), a film completed five years after its shooting due to lack of funds, a “little intellectual film,” a work about the educated class. Shot in 35mm and transferred to digital, this black-and-white film follows Zhuzi, a young man living in Hangzhou, also known as Paradise for its natural beauty. It captures a sense of alienation as Zhuzi, plagued by an unknown ailment, lifelessly goes about his daily life and seemingly drifts from one romantic relationship to another. From what illness could he be suffering? Scenes of doctor visits reveal little. The fragmented narrative reveals even less.

An intriguing landscape ink painting–demonstration sequence, more than four minutes long and appearing before the title card, provides cues for how to read this film. Trained as an oil painter at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (renamed China Academy of Art) in Hangzhou, before his interest turned to photography and film, Yang understandably has spent a lot of time contemplating the art of painting. Chinese ink painting occupies an essential place in traditional intellectual life as an educated person in ancient times was expected to master the Four Arts: qin(zither/music), qi (go/board game), shu (calligraphy), and hua (painting). Minimalist static shots capture the making of a traditional landscape ink painting, accompanied by a voice-over explaining the aesthetic: from the mastery of brushwork and the use of ink to the art of composition and the poetry embedded in each painting; more important than the representation of a landscape is the expression of the state of mind of the creator.

The film’s multiple montage sequences, stitching together shots of natural scenery, commerce, street life, strangers, and train tracks, might not serve a narrative purpose but they conjure up a psychological and poetic landscape (much like what one finds in an ink painting) whereby Zhuzi lives out his existential crisis. His joylessness, aimlessness, and disengagement bring to mind the works of film auteur Michelangelo Antonioni, whose characters suffer the discontent and ennui associated with modernism. Yang, who was born during the Cultural Revolution and came of age when China was rapidly modernizing and transforming into a quasi–market economy, has effectively mapped out the state of mind of a character experiencing life evolving at breakneck speed.

Yang Fudong, An Estranged Paradise (Mohsheng Tiantang), 1997-2002. 35mm film transferred to video (black-and-white, sound). 76 min. Gift of Marian and James H. Cohen in memory of their son Michael Harrison Cohen

Situating this film in the context of filmmaking in China at the time it was made, Yang, very much like his contemporaries Zhang Yuan, Lou Ye, Wang Xiaoshuai, and Jia Zhangke, among those known as Sixth Generation filmmakers, drew inspiration from the fast-changing world he lived in. This generation has witnessed the most turbulent transformations in Chinese society in modern times. A decade of Cultural Revolution (1966–76), the great proletarian movement, was quickly followed by economic reforms that opened up China to influences from the outside world. The brutal crackdown on the 1989 Tiananmen student movement dealt a severe blow to the openness, but it was followed by China’s unimaginably rapid rise that made the country the global power we know today. Sixth Generation films provide observant studies of life undergoing drastic change. Like An Estranged Paradise, other films deal with the loss and alienation experienced by the young generation, such as Zhang’s Beijing Bastards (1993) and Jia’s Xiao Wu (1997) and Platform(2000).

Now focusing on photography and media artworks, Yang might have chosen a different path from the Sixth Generation filmmakers, but he continues to reflect on life in his country. This “little intellectual film” would set the tone for Yang to further explore the experiences of the educated class. Most notable is the work Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest (2003–07), a series of five films inspired by an ancient legend about seven intellectuals so disturbed by world politics and matters that they retreat into the woods to live a life of drinking and merrymaking. There are intellectuals who choose resignation, but Yang carries on, engaging with the evolving world through his creative work.

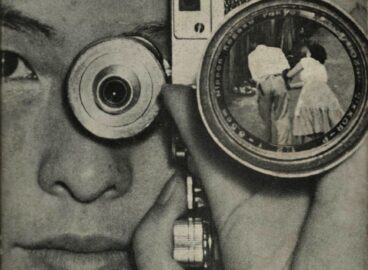

Read the essay by Guggenheim curator X Zhu-Nowell on another complex and fascinating video work, Zhang Peilli’s Document on Hygiene No. 3 on the Checklist blog.