Thoroughly committed to novelty, invention, and atomic and space-age practices, the Crystalist group proposed completely new directions for art in Sudan in the 1970s. In this essay, which situates the group’s 1976 manifesto published in a Khartoum newspaper within the artistic context of the time, Anneka Lenssen also discusses artistic practices that took on Crystalist themes of transparency and dualism, among them an intriguing exhibition in 1978 by Muhammad Hamid Shaddad that featured stacked ice blocks surrounded by plastic bags filled with colored water.

Read the translated manifesto here.

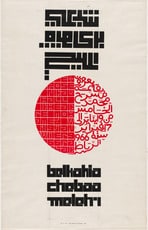

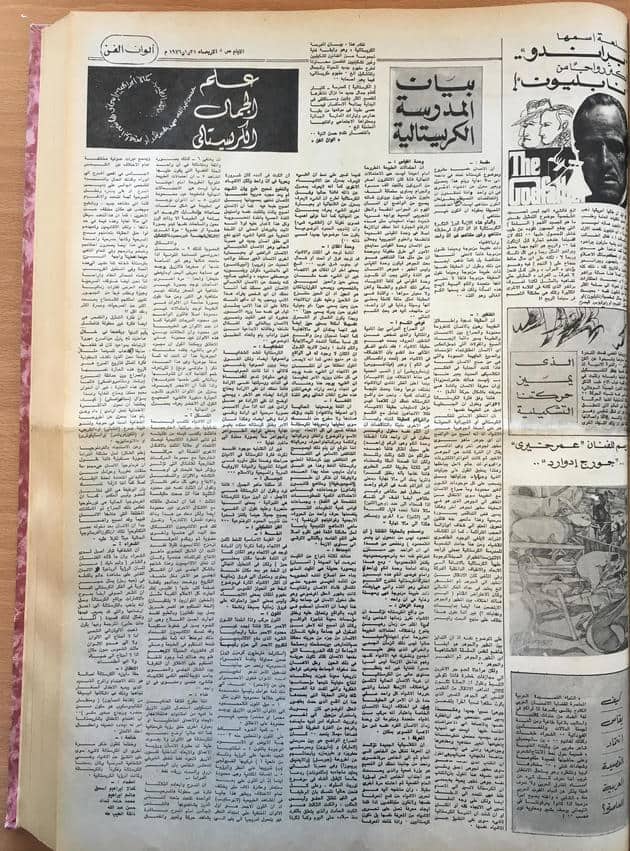

The first published declaration, or manifesto, of the Crystalist school appeared in the arts section of Khartoum’s al-Ayyam newspaper on January 21, 1976.1Hisham Abdallah, Hashim Ibrahim, Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, Muhammad Hamid Shaddad, Naiyla Al Tayib, “Bayan al-Madrasa al-Kristaliyya (Declaration of the Crystalist School),” al-Ayyam, January 21, 1976. Signed by artists Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, Muhammad Hamid Shaddad, and Naiyla Al Tayib, as well as Hisham Abdallah and Hashim Ibrahim, it delivered aesthetic commentary on such weighty categories as time, knowledge, the measurement of space, language, beauty, and the contingency of the elements of plastic art. The typeset manifesto filled nearly a full page of al-Ayyam, and it matched its bold occupation of space with the impudence of its pronouncements. The Crystalists not only characterized their project as liberal (at a time when Sudan followed a version of socialism as official policy), but they also characterized the world as infinite and unbounded; sought to claim pleasure as a means to uncover truth; understood appearances and perceptions of solid objects to be mere suggestions rather than denotations; and embraced an unorthodox materialism based upon mutual contradiction. As such, the manifesto bucked two prevailing ethoses in the Sudanese modern arts, that of the hybrid expressions of heritage forms associated with the senior faculty at the College of Fine and Applied Art in Khartoum, and of the popular cultural activism favored by leftist critics (holding strong even after the military regime of Colonel Gaafar Mohamad el-Nimeiri began to suppress the activities of the Sudanese Communist party, its former ally).2For discussion of the three “tendencies” in play in this moment, see Salah Hassan Abdullah, Musahamat fi al- Adab al-Tashkili,1974–86 (Khartoum: Mu’assasat Arwiqa lil-Thaqafa wa-al-‘Ulum, 2005), 105–89. Abdullah also identifies a fourth tendency, that of the “traditionalist right,” but it seems to have coalesced slightly after the main Crystalist interventions. By 1976 Shaddad was already a controversial figure in his own right, having captured attention as an art student in the years 1970–74 with his John Lennon glasses, interest in Happenings and conceptualist experiments, and antipathy toward Marxist-Leninist thought.3I have drawn upon the archived transcripts of a number of vibrant online discussions of artists and events in the 1970s Sudanese art world to write this account. Description of Shaddad from Hassan Musa, “Ma‘rad al-Insan al-Jalis,” Sudan for all, December 11, 2013, http://sudan-forall.org/forum/viewtopic.php? p=66249&sid=ee99e9922c80546764decb4424c00182. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, given Shaddad’s early reputation as a nonconformist, the cultural journalists at al-Ayyam—a leftist-oriented group headed by Hassan M. Musa—opted to preface the Crystalist manifesto with a brief statement of skepticism mixed with tolerance. Commending the artists’ ambition but (implicitly) criticizing their failure to ground theory in praxis, they contextualized the manifesto for readers in the following way:

It is an artistic document of the group of plastic artists and non-artists comprising the effort to adumbrate a new understanding of art, beauty, and form, etc. That is, a “Crystalist” understanding, to use the expression of its founders. The Crystalists, as a school, as a trend, as a new aesthetics—we are still waiting for its greater explication and presentation. We will be satisfied at the start with tracking the inquiry, its value as rebellion against us, in position among the remaining schools and tendencies in aesthetic practice, its social content, prospective horizons, etc. In short, we extend an affirmation of good faith . . .4Statement preceding “Bayan al-Madrasa al-Kristaliyya ( Declaration of the Crystalist School),” al-Ayyam, January 21, 1976.

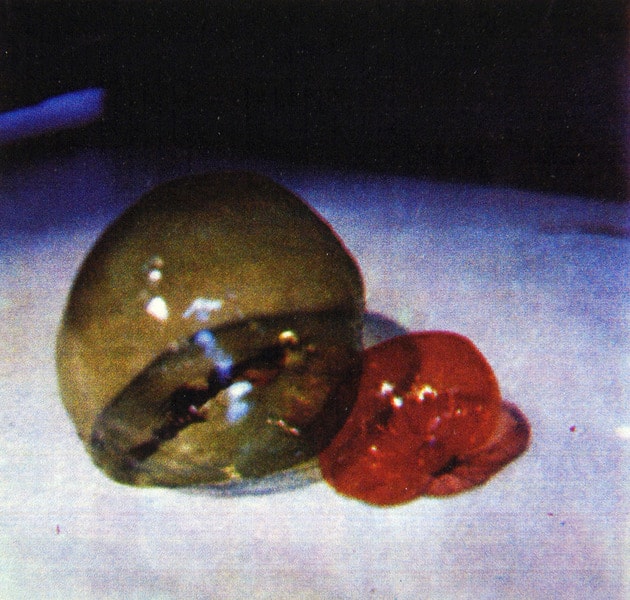

The volume Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents (2018), edited by Sarah Rogers, Nada Shabout, and myself, features an English translation of the full Crystalist manifesto of January 1976—rendered with great sensitivity and care by Nariman Youssef. As a preview of the book, we are using the post online platform to make the translated text freely available. Of all the texts we selected for the anthology, the Crystalist manifesto is perhaps the most exemplary “primary document.” Not only does it articulate a series of artistic positions that were then in the making but it also seems to aspire to historicity by outlining principles for future action. The Crystalists never made good on the “faith” the critics of al-Ayyam extended to them in the sense of organizing energies around class struggle or rural development, but they did enact a lasting legacy. Wielding a set of commitments to novelty, invention, and atomic and space-age practices, they proposed some wholly new directions for art in Sudan. For Shaddad and Al Tayib, many of their innovations took form via their critical use of the exhibition space. Consider how later in 1976, Al Tayib organized an unusual exhibition titled Ordinary Mirrors, an installation of fragments of mirrors, in which the gallery space itself became artistic content.5Ordinary Mirrors was criticized in the press, prompting Al Tayib to publish a response in al-Ayyam on September 21, 1976. See Abdullah, Musahamat, 109. Or how in 1978, Shaddad organized an exhibition of a stacked construction of ice blocks surrounded by plastic bags that he had filled with colored water, which constituted a physical exploration of such Crystalist themes as transparency and dualism. These events may be understood as provocations to a variety of institutional systems, not least of which the niceties of a local art scene that catered to the diplomatic corps.6Artist Elnour Hamad, who was a contemporary of Shaddad’s at the art school, recalls with amusement how one embassy employee arrived at the 1978 exhibition only to spy the melting ice and the general disarray, spin around, and flee the scene. Hamad, “Bayn Burtubil wa Apedemak,” SudaneseOnline, March 26, 2004, http://sudaneseonline.com/cgi-bin/sdb/2bb.cgi?seq=msg&board=13&msg=1139077595&rn=91.

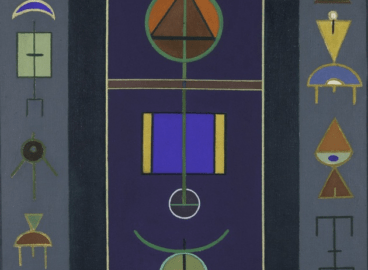

Throughout this period of Crystalist activities, Ishaq, Shaddad, and Al Tayib were operating as a school only in the loosest of senses. Ishaq was the senior member and taught painting at the College of Fine and Applied Art in Khartoum, and her career followed a different trajectory than that of her students Shaddad and Al Tayib. She faced fewer accusations of dilettantism, most likely because her work retained many of the themes for which she was already known: tales of spirits in Sudan learned at the knees of the “grandmothers,” inflected by a pedagogical interest in translating Sudanese cultural forms into artistic use.7See Ishaq’s discussion in Kamala Ibrahim Ishaaq: Painter, directed by Frederique Cifuentes Morgan, film, 10 min., 15 secs., https://vimeo.com/251297948. Characterization of Ishaq’s contribution to the education of Sudanese students from Rashid Diab, in Salah M. Hassan, The Art of Rashid Diab (Boston: Museum of the National Center of African-American Artists, 1994), 40. The appeal of the Crystalist platform, for Ishaq, was the feminist element of its effort to instantiate an alternative kind of interior knowledge.8See discussion in Contemporary Arab Women’s Art: Dialogues of the Present, ed. Fran Lloyd (London: WAL, 1999), 189. Once joining the Crystalists, Ishaq made paintings depicting women suspended within transparent, immaterial, cubes of glass. Existing in contingent, crystal space, they opposed—or at least troubled— the masculine empirical world view that established the norm. If taken as a group, then, the Crystalists are seen as delivering a riposte to the 1960s–era Khartoum school and its emphasis on heritage explorations (as had been implemented with greatest success by artists Ibrahim El-Salahi and Ahmed Shibrain). But Shaddad and Al Tayib also took the riposte several steps further. Not only did they abandon the cause of appealing to an imagined Sudanese everyman and demand sophistication from visitors, but they also waged Dada-like attacks on the very same exhibition system’s claims to civilizational edification. They even published criticism of the al-Ayyam critics and the latter’s archaicizing power structures. Famously, Shaddad and Al Tayib once published a letter addressed to Hassan M. Musa, Abdallah Bola, and the other “nomadic tribals” of the plastic arts.9Mentioned by Hamad, “Bayn Burtubil wa Apedemak.” The charge of “nomad” would seem to mean to invoke both the corruption of tribal governance and the government’s cultural policy of decentralized development via cultural programs with rural groups and linguistic communities (discussed below).

In terms of historiographic legacy, the Crystalists represent one of the first episodes in Sudanese modernism to be entered into the annals of global contemporary art, entering via the art fairs and biennials of the 1990s and 2000s. As far as we have been able to track, the majority of modern art historians in the North Atlantic universities first became aware of the Crystalists around 1995 or so, when prominent Cornell professor Salah M. Hassan wrote about Sudanese arts inSeven Stories about Modern Art in Africa, the catalogue for the Whitechapel Gallery exhibition of the same title, and translated a Crystalist text for the volume’s appendix.10Salah M. Hassan, “The Khartoum and Addis Connections: Two Stories from Sudan and Ethiopia,” in Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa, eds. Clementine Deliss and Catherine Lambert (New York: Whitechapel, 1995): 105–25. The exhibition was organized as a parallel event for the London festival Africa 95. Since this time, further Crystalist texts have been published in Arabic, allowing us to now re-characterize the text that appears in the catalogue under the title “Crystalist Manifesto” as a 1980 exhibition statement by Shaddad. See Abdullah, Musahamat, 238–40. In this initial introduction, Hassan emphasized the Crystalists’ sophisticated engagement with international currents and their implicit critique of Khartoum school tenets. By the end of the decade, in turn, analysis of the Crystalist oeuvre gained another dimension via a growing discussion of “African conceptualism,” sparked in part by the landmark exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s, which featured a catalogue essay on the subject by Okwui Enwezor.11Okwui Enwezor, “Where, What, Who, When: A Few Notes on African Conceptualism,” in Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s (New York: Queens Art Museum, 1999), 109–17. In 2001, when Hassan and Olu Oguibe organized the greatly influential exhibition Authentic/Ex-Centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art for the Venice Biennale, their catalogue essay featured Shaddad’s conceptual work and emphasized its rarity as a challenge to the academic notions that dominated many national art schools on the continent.12Salah M. Hassan and Olu Oguibe, “Authentic/Ex-Centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art,” inAuthentic/Ex-Centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art (Ithaca, NY: Forum for African Arts, 2001): 10– 23.

In spite of ongoing acclaim for the Crystalists’ interventions in Khartoum, the archival record of their writing and exhibitions has often proven difficult to access, let alone to parse. That the manifesto and other statements resist easy translation is, of course, a testament to the intellectual heft of the writing. But equally, the diffuseness of the archive reflects the hardship of life under dictatorship, which lasted until 1985 only to dovetail in 1983 with the catastrophically deadly resurgence of civil war. Sudanese artists, curators, and critics had long faced travel restrictions, and the circulation of their scholarship outside Sudan has been similarly constricted. Musa, the artist and critic who oversaw al-Ayyam’s cultural pages in the 1970s, has published a detailed account of the constraints as well as the hopeful commitments of the period in his remarkable article “The Party of Art: When the People Entered the Gallery.”13Hassan M. Musa, “The Party of Art: When the People Entered the Gallery,” South Atlantic Quarterly 109 (2010): 75–94. As he makes clear, the particular violence of life under Nimeiri—and here we must take note that on the very date the Crystalists published their manifesto, El-Salahi was being held in Cooper prison without trial—can also flatten the ideological complexity of the artistic documents that remain from the period. When the archival record of these years is scrutinized from our position in the present, debate of any kind can appear to be a valiant struggle against the regime. The mere fact that Musa and other journalist-artists found ways to use al-Ayyam as a platform for veiled critiques of government policy can be cited as evidence of a leftist effort to foster democratic participation, and, indeed, of that effort’s ongoing, underground resistance activity.14Ibid., 89.

In our own endeavor to assemble a more complete archive of Crystalist texts, we were spurred on by a desire to highlight the other debates about authenticity that took place in Sudan—in texts we hoped might complement the Crystalist materials and give a better sense of the stakes of their discussion of transparency without objecthood. Our search was aided most directly by the indispensable documentary history Contributions in Artistic Writing, 1974–1986 (Musahamat fi al-Adab al- Tashkili, 1974–86), compiled by the Khartoum-based artist and scholar Salah Hassan Abdullah, who was himself a participant in the debates.15Abdullah, Musahamat. Abdullah’s scholarship helped us to establish January 21, 1976, as the publication date for the first Crystalist manifesto (rather than 1978, as has been reported), and to identify the text that had hitherto circulated as the manifesto as a 1980 statement by Shaddad.16We are confident in this revised dating, having confirmed the January 21, 1976, date by reference to the originalal-Ayyam newspaper issue. The individual artists associated with the Crystalists did publish subsequent texts developing the ideas, including at least one in 1978. Abdullah, Musahamat, provides the citations. Our sense of the importance of the Sudanese debates was fortified, in turn, by the recent efforts of the Sharjah Art Foundation to launch a major research and exhibition initiative devoted to Sudan’s modernism(s), overseen by director Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi in collaboration with Salah M. Hassan.17See http://sharjahart.org/sharjah-art-foundation/exhibitions/the-khartoum-school-the-making-of-the-modern- art-movement-in-sudan-1945-pre. Ultimately, for the purpose of representing the discursive energies of Sudan’s 1970s art world in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, we opted to excerpt two pieces of newspaper writing by al-Ayyam’s own critical team: commentary by Bola and by Mohamed Abusabib, both of whom—over a long, recurring series of responses— purport to analyze the “crisis” of the visual arts as a bourgeois product and seek to articulate better pathways to a transformative socialist art.18The aesthetic philosophy of Ernst Fischer in The Necessity of Art was a common touchstone in this oeuvre, as it was in the writing of Palestinian leftist artists of the same era.

Against the ground of intellectual authority and structured political commitment promoted in the cultural pages of al-Ayyam, it is the self-professed liberals who emerge as the most radical. The conundrum is a crucial one, for it is common to conditions of authoritarian rule in these decades. We know that beginning around 1960, the most promising and highly trained plastic artists in Sudan began to try to develop an art that would represent the “people of Sudan” (with “people” having a distinct socialist cast)—and in so doing, made a conscious break with the foreign values they had studied in London.19Musa, “The Party of Art,” 81–82. As El-Salahi himself has noted, he perceived that the people did not accept the art that he and his generation brought back to their country. The challenge was thus to figure out what the people sought from art. He met that challenge by recourse to Arabic calligraphy and the creation of decorative units from Sudanese folk entities and forms. Later, after a May 25, 1969 coup by “free officers” brought Nimeiri to power by overturning the brief period of multiparty democracy in place from 1964 to 1969, there remained excitement (short-lived) around the state’s proclaimed commitment to “Sudanese socialism.” Communist party members served in the Revolutionary Council and continued leftist initiatives in the field of culture, such as rural outreach programs. At a high point in this optimism, in 1970, the student union of the College of Fine and Applied Art made an official endorsement of the new government—a move for which they were rewarded by Nimeiri’s attendance at their 1970 graduation, where he delivered a speech defending the role of art in development and progress.20Ibid., 85. These events only narrowly preceded a major break in solidarity in July 1971— when a leftist faction tried to take over the government with intentions of more closely allying with the Soviet Union—and they are often seen as the beginning of the end for artistic autonomy.21Ibid.; Abdullah, Musahamat, 16. Whereas “questions of culture, development, and national unity were real, and the regime was forced to face up to them in its official conferences and within its routine cultural work,” the livelihoods of artists in Sudan became entangled in the question of loyalty to the state.22Musa, “The Party of Art,” 86. This neutralized the role of artists in political action. When, beginning in 1974, artist discussions moved beyond the college walls and onto the pages of newspapers and magazines, they were almost always displaced to a plane of hypothetical commentary.231974 periodization is Abdullah’s.

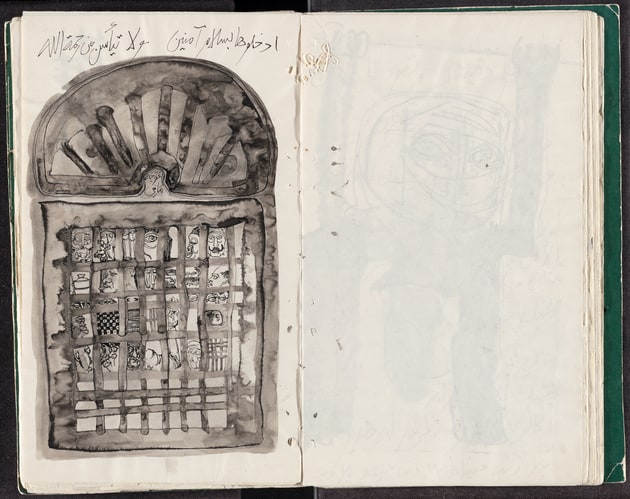

In the same period, El-Salahi—away in London since 1969—was called back to Sudan to fill a position in the Ministry of Information and to oversee an expansion of its cultural portfolio. Nimeiri’s regime had managed to reach a cease-fire agreement to end the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–72) and was seeking to develop structures of governance. Official cultural policy in Sudan settled upon the relatively progressive policy of promoting cultural diversity and decentralization, an approach that included efforts to preserve the languages and dialects spoken by the peoples so as to cultivate the free cultural development of rural and tribal communities, and other recognizably Communist models of development.24Musa, “The Party of Art,” 86–87. In this setting, El-Salahi not only helped to set up a Ministry of Culture, but he also ran a television show, Bayt al-Jak, which was devoted to open discussion of art, culture, and social issues. The same purported commitment to freedom and diversity would become a double-edged sword for El-Salahi, however. In September 1975, after he crossed a regime redline on his television show, he was targeted: accused of “anti- government activity,” beaten, and taken to Cooper prison in Khartoum North, where he was held until March 16, 1976. In the days immediately following his release, when he was placed under house arrest, El-Salahi worked through the experience by creating a group of ink drawings in what is now known as the Prison Notebook. To make these drawings, the artist coaxed images of captive spirits and latent presences from a limited palette of watery black inks, then added text giving accounts of imprisonment or relaying meaningful passages from the Qur’an. One features an image of a heavily reinforced barred door—visibly holding an assemblage of wraiths and people captive—over which El-Salahi wrote, “Enter it in peace, safe” (15:46), and “No one despairs of the mercy of God” (12:87). The effect is a mixing of sincerity and sardonic surrender.

Once the conceptualist bent of the Crystalist writing is considered in contrapuntal relationship to El-Salahi’s career and its double bind of celebration and punishment, the group’s invocation of clear, crystalline presences takes on newly poignant meaning. Consider, for example, the Sufistic aspects of El-Salahi’s creative production before, during, and after his imprisonment. The artist has described his ritual preparations for the act of creation, by which he enters into a prayerful state and offers himself and his body as a vessel for God.25Sarah Adams, “In My Garment There Is Nothing but God: Recent Work by Ibrahim El Salahi,” African Arts 39 no. 2 (Summer 2006): 26–35. A critique of the apolitical qualities of this stance is developed by Hassan M. Musa, “El-Salahi, the Wise Enemy: Between the Artist of the Authority and the Authority of the Artist,” Ibrahim El- Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, ed. Salah M. Hassan (Long Island City, NY: Museum for African Art, 2012). There is discussion of Sufism in the Crystalist manifesto as well, appearing under the sub- category “Transparency.” But the manifesto pushes toward a different conclusion. It explicitly distinguishes the kind of transparency sought by the Crystalists from that sought by Sufism. The distinction turns on volition. If the Sufistic mode of behavior calls for a negation of personal volition such that the self is dissolved, then the Crystalists’ dissolution must be recognized as requiring volition. They assert that “negating volition is itself a volitional act.” As a result, an endless dialectic of volition-negation is established, such that an “infinite crystal is created,” and their aesthetic discourse sustains the cosmic fact of constant oscillation between essences and outward semblances. Further, in the same section of the manifesto, Ishaq, Shaddad, and Al Tayib propose to make crystal a kind of trans-religious awareness or commitment, reminding readers that a number of religions both ancient and modern, spiritual and secular—Manichaeism, Orphism, Christianity, and Islam—embrace its importance.

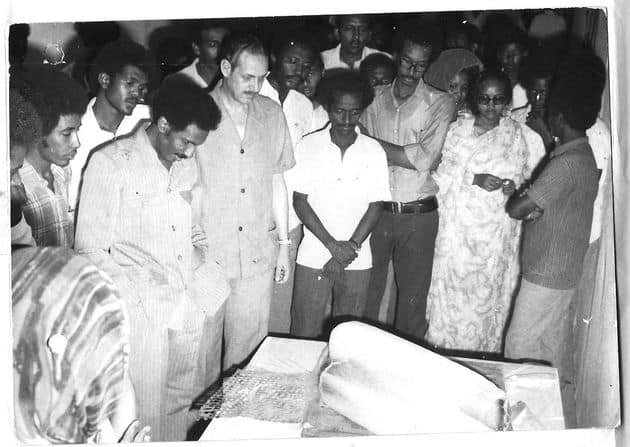

The preservation of a role for volition amid dissolution seems to have been central to Shaddad’s efforts in Khartoum. In one controversial 1971 exhibition, for example, titled The Exhibition of the Seated Human Being, he seated the male model from his drawing class between a human skeleton and a raw leg of lamb, around which grouping he hung works of art that he’d tagged with prices given in the unit of kisses.26Hassan and Oguibe, “Authentic/Ex-Centric,” 15, 18. Subsequently understood as a kind of Happening, the exhibition raised questions about both the status of the human being as an entity situated between bones and flesh and the role of desire in the human value of art. Shaddad challenged anyone in the audience who wanted to acquire the work to simply kiss him—thereby proposing to make a show of affection take the place of contractual relations of commerce. The price proved far too heavy for the population of the College of Fine and Applied Art at that time. Hassan M. Musa recalls that no one paid it, their non-action prompting Shaddad to launch into a speech calling for a “liberation of instincts” as a necessary step to liberate the human being and, in turn, to save humanity from its own carceral history.27Musa, “Ma‘rad al-Insan al-Jalis.” This online thread includes details of Shaddad’s other exhibitions. One also took place in the art history room at the College of Fine and Applied Arts and featured an old toilet seat, vegetables, fruits, and meat. Visitors were brought into the room, which was kept dark, and led around by flashlight. Another piece, from 1973, was enacted using the group name “Liberal Thought Society.” After an issue with the college’s toilets had produced a foul smell, Shaddad issued a text that claimed proprietary rights to the odor.

The Crystalists concluded their 1976 manifesto by reiterating that “the crystal is nothing but the denial of the objectification of objects. It is infinite transparency. We painted the crystal, we thought about the crystal, and so the Crystalist vision came to be.” The reference to painting the crystal is likely a reference to Ishaq in particular, who, unlike Shaddad and Al Tayib, continued to work in pigments on canvas. Shaddad, by contrast, would pursue the denial of objectification at the level of materials and their manipulation. One of his earliest experiments with colored water as form had come with his graduation show in 1974, when he piled bags of water—tinted in different colors—in a corner of his studio. This assemblage served as a shape-shifting, anti-object interior to a hard exterior that he had prepared outside: a pile of old concrete molds that, from construction sites, he had welded into a wall piece resembling pigeon towers.28Hamad, “Bayn Burtubil wa Apedemak.” As a spatialized manifestation of proto-Crystalist ideas, the installation might be taken as a rumination on the general nature of “things,” such that their existence in the world necessarily entails the coexistence of invisible (but potentially sensed) interior states and the hardened “face” by which they interact with the world. By 1976 the discussion had opened to more explicitly insist on liberation from all imposed ontological categories. “Now that man has entered the technological age,” the Crystalists wrote, “present morphology has become almost a burden on him.” The artists not only foregrounded change and constant “becoming” as defining forces in art practice, but they also spoke in favor of multiplicity, which they recognized in the coexistence of distant possibilities that otherwise seem contradictory.

Shaddad issued another statement of Crystalist ideas in late 1980, on the occasion of his exhibition The Artist and Thought (it, too, will be published in translation inModern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents). It puts a still-sharper point on the situation. Perhaps holding the progressivist and so-called materialist frameworks of the dominant critics in the Sudan in mind, he writes: “Crystalists attest that there is no empirical knowledge and that everything ever said about empirical knowledge is a myth. The human mind has never evolved and will never evolve through experience. The basis for Crystalist thought is that receptivity to knowledge is also knowledge.” Nor did Shaddad have confidence in the law of evolution. Citing the presence of two vestigial breasts on his chest, he emphasized instead a multiple coexistence of morphological shapes and even “organs” arising out of pleasure and out of function (rather than producing pleasure or function). By then, the Crystalist project had been staging its disagreements with Sudan modernist pieties for years. The Crystalists wanted artists, whom they conceived as entities in a shifting world of chemicals and forces, to be freed from taking a position on one side of the dialectic or the other. By positing the artist’s existence within the dialectical movement of quantity and quality, they define art as a transparent crystallization of the universe’s multivalence. Just as the editors of al- Ayyam had predicted in 1976, the Crystalist artists never worked out any particular praxis on the ground or in their studios as the basis for their imaginations. Yet the openness of their program was their position—and it promised to engage with an unbound world beyond any named or weaponized ideology. As Shaddad himself put it as the final line of his 1980 exhibition text, “I conclude without asking you to commit yourself to anything.”

- 1Hisham Abdallah, Hashim Ibrahim, Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, Muhammad Hamid Shaddad, Naiyla Al Tayib, “Bayan al-Madrasa al-Kristaliyya (Declaration of the Crystalist School),” al-Ayyam, January 21, 1976.

- 2For discussion of the three “tendencies” in play in this moment, see Salah Hassan Abdullah, Musahamat fi al- Adab al-Tashkili,1974–86 (Khartoum: Mu’assasat Arwiqa lil-Thaqafa wa-al-‘Ulum, 2005), 105–89. Abdullah also identifies a fourth tendency, that of the “traditionalist right,” but it seems to have coalesced slightly after the main Crystalist interventions.

- 3I have drawn upon the archived transcripts of a number of vibrant online discussions of artists and events in the 1970s Sudanese art world to write this account. Description of Shaddad from Hassan Musa, “Ma‘rad al-Insan al-Jalis,” Sudan for all, December 11, 2013, http://sudan-forall.org/forum/viewtopic.php? p=66249&sid=ee99e9922c80546764decb4424c00182.

- 4Statement preceding “Bayan al-Madrasa al-Kristaliyya ( Declaration of the Crystalist School),” al-Ayyam, January 21, 1976.

- 5Ordinary Mirrors was criticized in the press, prompting Al Tayib to publish a response in al-Ayyam on September 21, 1976. See Abdullah, Musahamat, 109.

- 6Artist Elnour Hamad, who was a contemporary of Shaddad’s at the art school, recalls with amusement how one embassy employee arrived at the 1978 exhibition only to spy the melting ice and the general disarray, spin around, and flee the scene. Hamad, “Bayn Burtubil wa Apedemak,” SudaneseOnline, March 26, 2004, http://sudaneseonline.com/cgi-bin/sdb/2bb.cgi?seq=msg&board=13&msg=1139077595&rn=91.

- 7See Ishaq’s discussion in Kamala Ibrahim Ishaaq: Painter, directed by Frederique Cifuentes Morgan, film, 10 min., 15 secs., https://vimeo.com/251297948. Characterization of Ishaq’s contribution to the education of Sudanese students from Rashid Diab, in Salah M. Hassan, The Art of Rashid Diab (Boston: Museum of the National Center of African-American Artists, 1994), 40.

- 8See discussion in Contemporary Arab Women’s Art: Dialogues of the Present, ed. Fran Lloyd (London: WAL, 1999), 189.

- 9Mentioned by Hamad, “Bayn Burtubil wa Apedemak.” The charge of “nomad” would seem to mean to invoke both the corruption of tribal governance and the government’s cultural policy of decentralized development via cultural programs with rural groups and linguistic communities (discussed below).

- 10Salah M. Hassan, “The Khartoum and Addis Connections: Two Stories from Sudan and Ethiopia,” in Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa, eds. Clementine Deliss and Catherine Lambert (New York: Whitechapel, 1995): 105–25. The exhibition was organized as a parallel event for the London festival Africa 95. Since this time, further Crystalist texts have been published in Arabic, allowing us to now re-characterize the text that appears in the catalogue under the title “Crystalist Manifesto” as a 1980 exhibition statement by Shaddad. See Abdullah, Musahamat, 238–40.

- 11Okwui Enwezor, “Where, What, Who, When: A Few Notes on African Conceptualism,” in Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s (New York: Queens Art Museum, 1999), 109–17.

- 12Salah M. Hassan and Olu Oguibe, “Authentic/Ex-Centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art,” inAuthentic/Ex-Centric: Conceptualism in Contemporary African Art (Ithaca, NY: Forum for African Arts, 2001): 10– 23.

- 13Hassan M. Musa, “The Party of Art: When the People Entered the Gallery,” South Atlantic Quarterly 109 (2010): 75–94.

- 14Ibid., 89.

- 15Abdullah, Musahamat.

- 16We are confident in this revised dating, having confirmed the January 21, 1976, date by reference to the originalal-Ayyam newspaper issue. The individual artists associated with the Crystalists did publish subsequent texts developing the ideas, including at least one in 1978. Abdullah, Musahamat, provides the citations.

- 17

- 18The aesthetic philosophy of Ernst Fischer in The Necessity of Art was a common touchstone in this oeuvre, as it was in the writing of Palestinian leftist artists of the same era.

- 19Musa, “The Party of Art,” 81–82.

- 20Ibid., 85.

- 21Ibid.; Abdullah, Musahamat, 16.

- 22Musa, “The Party of Art,” 86.

- 231974 periodization is Abdullah’s.

- 24Musa, “The Party of Art,” 86–87.

- 25Sarah Adams, “In My Garment There Is Nothing but God: Recent Work by Ibrahim El Salahi,” African Arts 39 no. 2 (Summer 2006): 26–35. A critique of the apolitical qualities of this stance is developed by Hassan M. Musa, “El-Salahi, the Wise Enemy: Between the Artist of the Authority and the Authority of the Artist,” Ibrahim El- Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, ed. Salah M. Hassan (Long Island City, NY: Museum for African Art, 2012).

- 26Hassan and Oguibe, “Authentic/Ex-Centric,” 15, 18.

- 27Musa, “Ma‘rad al-Insan al-Jalis.” This online thread includes details of Shaddad’s other exhibitions. One also took place in the art history room at the College of Fine and Applied Arts and featured an old toilet seat, vegetables, fruits, and meat. Visitors were brought into the room, which was kept dark, and led around by flashlight. Another piece, from 1973, was enacted using the group name “Liberal Thought Society.” After an issue with the college’s toilets had produced a foul smell, Shaddad issued a text that claimed proprietary rights to the odor.

- 28Hamad, “Bayn Burtubil wa Apedemak.”