Experimenting with ideas of disruption, participation, community, and institutional critique, Argentine artist Marta Minujín blindfolded and “kidnapped” fifteen audience members as part of Kidnappening, the opera-cantata-happening she organized with Gary Glover at the Museum of Modern Art in 1973. This essay explores the critical force and political potential of Marta Minujín’s seemingly naïve participatory performances, as well as her ambiguous position as both an insider and outsider in the 1970s New York art scene.

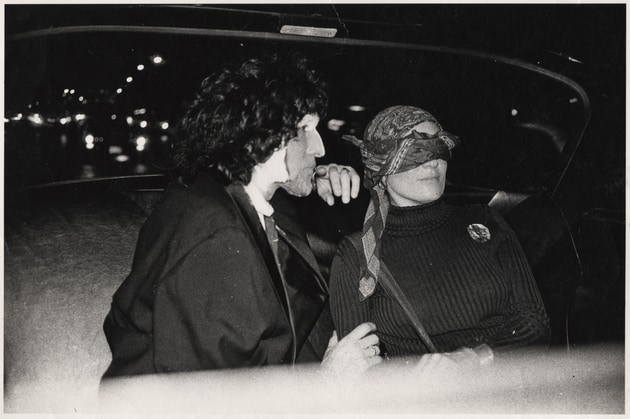

“Volunteers will be spirited away” reads the caption of a photograph in a New York Times article promoting a performance set to take place in MoMA’s sculpture garden on August 3–4, 1973.1Robert Shepard, “GOING OUT Guide,” New York Times, August 3, [1973], 16. The photograph shows the Argentine artist Marta Minujín, who is blindfolded; the title of the performance is Kidnappening. But spirited away to where? And for what purpose? By examining Kidnappening, this paper will explore the critical force and political potential of Marta Minujín’s seemingly naïve participatory performances, as well as her ambiguous position as both an insider and outsider in the 1970s New York art scene.

Minujín was a prodigal child of the 1960s Argentine avant-garde, born from the experimental hub of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires. She first traveled to New York in 1966 on a Guggenheim Fellowship and then lived between the Big Apple and Buenos Aires for the next decade. For most Latin American artists living in New York during this time, integrating into the city’s art scene was difficult. This was not the case for Minujín, who quickly made herself at home among the local avant-garde, collaborating with artists as diverse as Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol, and groups including the Judson Theatre Company crew and the Fluxus community. Minujín’s works from this period demonstrate a foreigner’s complex view of the city, investigating and putting into question the social tensions surrounding belonging. Through these explorations, Minujín stretched the boundaries of the art world to the extreme. She did so in a way that was conscious, strategic, and critical of her own dual role as an insider and an outsider.

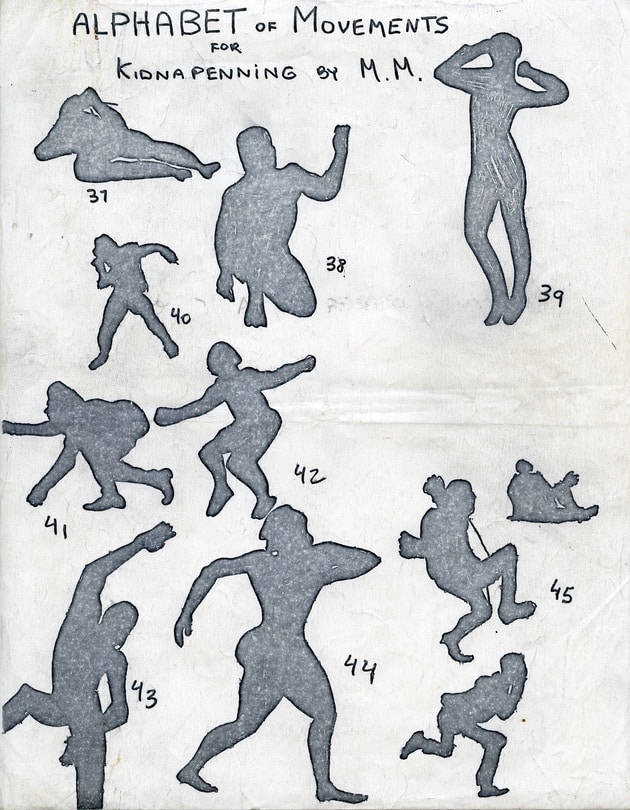

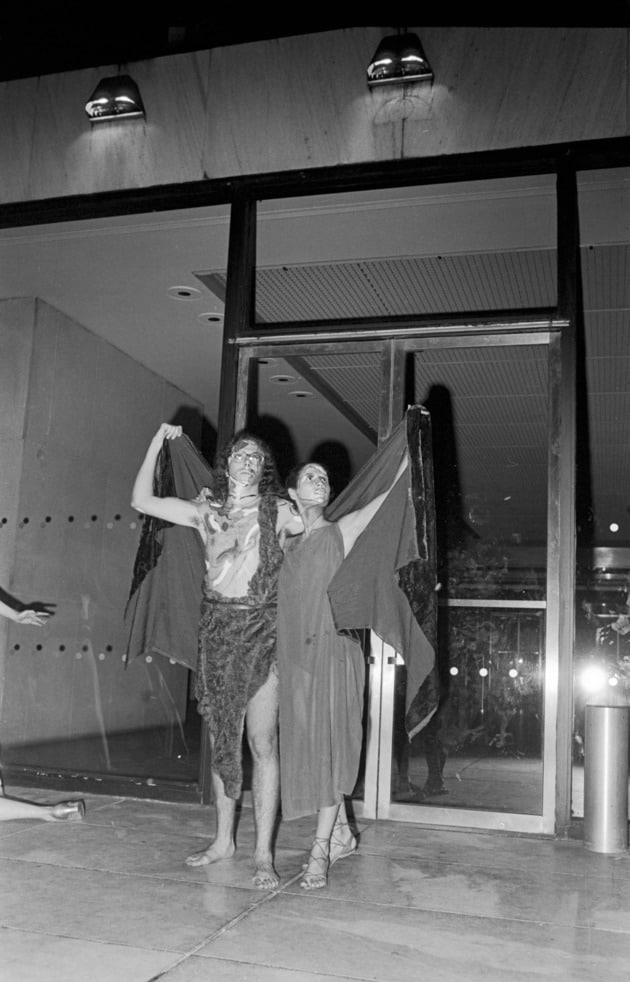

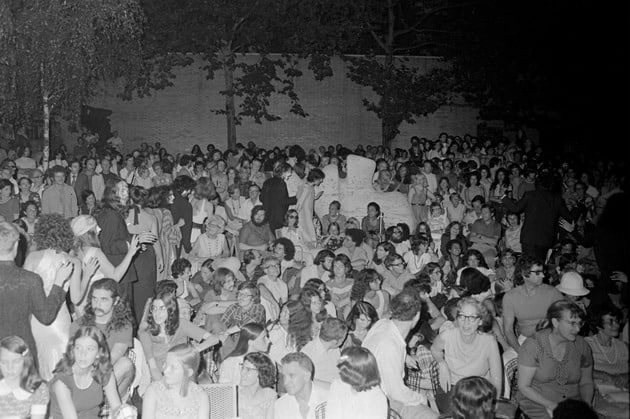

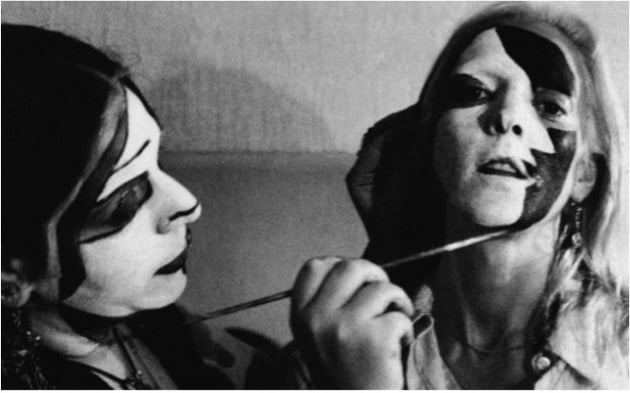

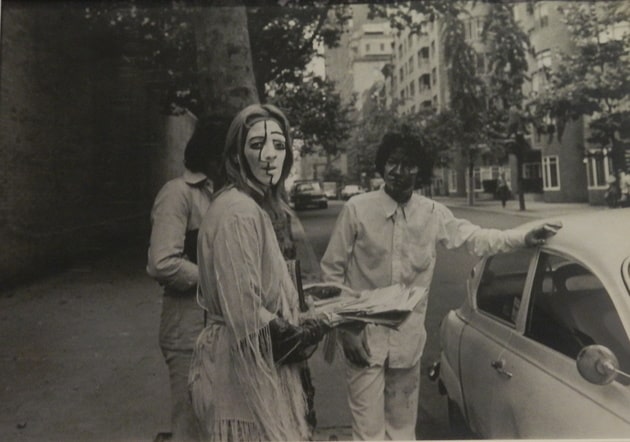

For MoMA’s 1973 Summergarden program, Minujín orchestrated an “opera- cantata-happening” titled Kidnappening with the help of Gary Glover.2The Summergarden program was sponsored by Mobil, and since 1971, offered free late-night weekend events during the summer in which a wide range of spectacles including music, dance, jazz, Egyptian belly dance and mimes were presented. According to MoMA’s records, that summer the program received a daily attendance of 1,200 people, with a season total of 56,000. For her August 3 and 4 performances, Marta received a budget of $400, with the rest needed coming from “the impossible or the miraculous.” Marta Minujín, “Kidnappening,” in “Kidnappening Folder,” n.d. Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria Fine Art. Translated from Spanish by the author. The event, which began at 8:00 p.m., was designed to pay homage to the recently deceased Pablo Picasso, and more than forty performers, their faces painted with Cubist compositions, were contracted to participate.3“I would take the cubist period, in particular ‘The mademoiselles d’Avignon.’” Marta Minujín, ibid. In the same spirit, the choreography included an “alphabet of [forty-four] movements […] derived from the poses used in Picasso’s art,”4Marta Minujín, “Picappening, Picassening, Picassonning,” in Minujín, “Kidnappening Folder.” with performers acting out the sharp lines and angles of Cubism. While dancing, the performers sang soliloquys in which they cited modern artists, philosophers, politicians, and poets.5The lyrics to be sung and screamed by the performers in this “opera-cantata-happening” were selected by Minujín with the help of Claudio Bedel, a Chilean poet who lived in New York City. In addition to many quotes from Picasso, there were lines from Cézanne, Renoir, Matisse, Derain, Braque, Brancusi, Duchamp, and the “Manifesto of Futurism” by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. The performers also repeated lines from thinkers such as Plato and even Mao Tse-Tung. From the latter, Minujín included: “When you do anything, unless you understand its actual circumstances, its nature, and its relations to other things, you will not know the laws governing it, or know how to do it, or be able to do it well.” Mao Tse-Tung, “Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War” (December 1936), in Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1:179. Interestingly, something similar could be said of Kidnappening. The work cannot be understood without paying attention to its actual circumstances—i.e., the museum setting—or to “its relations to other things,” such as the surrounding city and cast of characters.

Still, the work’s main act came at around 10:00 p.m., when the performers suddenly began to surround the audience. While repeating the word “kidnappening,” they grabbed fifteen spectators—most of whom had previously agreed to participate in the action—and took them from the event without further explanation. Those “kidnapped” were blindfolded, and taken to different New York locations, including a concert, an apartment on the Upper East Side, the French Consulate, a barbershop, and the Brooklyn Bridge.

The title Kidnappening combines the words “kidnapping” and “Happening.” Minujín had since 1965 been defining her participatory environments as “Happenings,” some of which were in collaboration with Alan Kaprow, who coined the term.6In 1967, with Kaprow and the artist Wolf Vostell, Minujín created the first international Happening, A 3 Country Happening. See Michael Kirby, “Marta Minujin’s ‘Simultaneity in Simultaneity,’”Drama Review: TDR 12, no. 3 (1968): 149–52; and Victoria Noorthoorn, ed., Marta Minujín: Obras 1959–1989 (Buenos Aires: Malba-Fundación Constantini, 2010), 74–75. Interestingly, it was fellow Argentine Oscar Masotta who, in 1967, criticized the overuse of the term, although he also noted that Minujín’s work was in constant flux and that it refused to follow the norms of what a Happening should be.7For more on Minujín’s place in between categories and Oscar Massota’s reading of her work, see Catherine Spencer, “Performing Pop: Marta Minujín and the ‘Argentine Image-Makers,’” Tate Papers, no. 2 (Autumn 2015), http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/24/performing-pop-marta-minujín-and-the-argentine- image-makers, accessed April 18, 2017. Kidnappening was, in fact, the last of a series of works given a title combining “Happening” with another word.

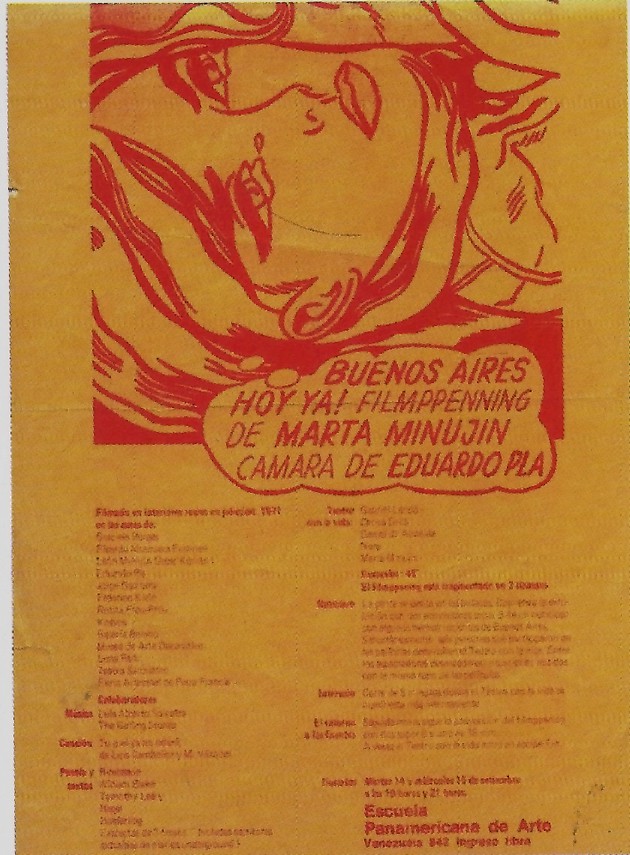

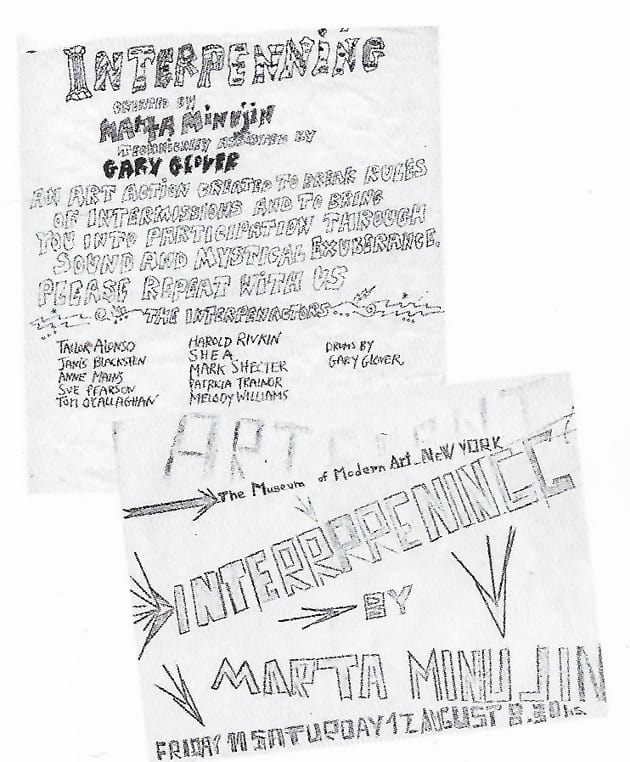

The first was the September 1971 event Buenos Aires, hoy ya! (Filmpenning), which was presented in the art school Escuela Panamericana de Arte in Buenos Aires and brought together movies, music, poetry, and the “theater of life.” Filmpenning was quickly followed by Interpenning, which was designed in collaboration with the artist and actor Richard Squire for the Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC and then staged in different locations throughout 1972. Invited to participate in MoMA’s Summergarden program for the first time in August of that same year, Minujín restaged Interpenning in collaboration with Chilean artist Juan Downey, who installed a labyrinth made of ultrasonic waves, an “invisible architecture” meant to “break the patterns and rules of an existing social situation and to create new patterns of interaction in which people participate more actively and more consciously.”8“Art Event Staged by Marta Minujin in Museum Garden,” press release no. 96 (August 1972), The Museum of Modern Art Press Release Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/pressarchives/4877/releases/MOMA1972010696.pdf?2010, accessed September 10, 2017. Finally, Interpenning was performed at the New York Avant Garde Festival, which was organized by Charlotte Moorman aboard the steamboat Alexander Hamilton on October 28, 1972.

In June 1973, Minujín organized Nicappening at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet benefit auction for survivors of Nicaragua’s recent earthquake. Again, the performers interrupted the institutional setting, screaming at the audience, “Have you realized what happened?” as a way to raise social consciousness.

Kidnappening was the fourth and final work in the “-ppening” series, and it can be understood as the dialectic synthesis of Minujín’s experimentations with the ideas of interruption, participation, and institutional critique. However, we must clarify that Kidnappening is a messy and complex synthesis—not a resolutive one. And moreover, due to the performative nature of the work, it must be reconstructed through Minujín’s and MoMA’s archives, which together add up to a fairly complete set of photographs and other documentation, including participant testimonies.

Kidnappening was the fourth and final work in the “-ppening” series, and it can be understood as the dialectic synthesis of Minujín’s experimentations with the ideas of interruption, participation, and institutional critique. However, we must clarify that Kidnappening is a messy and complex synthesis—not a resolutive one. And moreover, due to the performative nature of the work, it must be reconstructed through Minujín’s and MoMA’s archives, which together add up to a fairly complete set of photographs and other documentation, including participant testimonies.

Minujín’s preparatory notes indicate that she originally planned to title the event “Picappening” or “Picassening.” As she later recalled: “Picasso had died, and I was impacted and wanted to pay homage to him. […] I started flipping through the pages of a book with Picasso’s works. […] I remember it was very late at night, and the characters that would come to make up the show I was imagining started to take shape and to sing the words once spoken by Picasso. And I decided to make an Opera-Happening.”9Marta Minujín, “Kidnappening.” As Minujín detailed in a manuscript written shortly after the performance, the work would be an “opera, because in some moments arias would be sung, cantata because there would be many choruses, and happening, because at the end something really unexpected would happen, an overflow of incidentals.” In this new, mixed genre, the use of intermission and interruption as a concept behind Interpenningwas taken one step further to make the whole event a disruption.

She only later decided that the kidnappings would be the performance’s central focus. This decision might have been a whimsical one, or perhaps it was a marketing scheme, but in any case, we must acknowledge the conceptual shift that it entailed. Minujín paid homage to the master of modern painting with a performance exemplifying the broader move in art then taking place away from painting and toward the body and action.

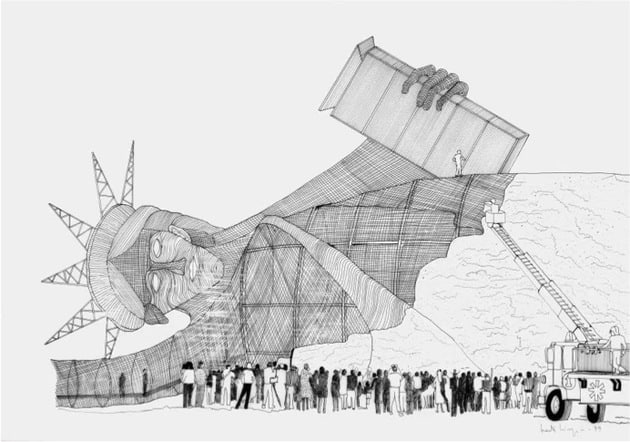

As Minujín later stated: “Picasso represents the freedom, the euphoria and the desperation to create and unroll the Ariadne’s thread that we all have inside ourselves. He is the greatest example for artists of the twentieth century, the innovator who shocked the most, to later see these shocks of his turned into canons.”10Marta Minujín, untitled article, La Nación, October 25, 1981. Cited in Marta Minujin: Happenings y Performances(Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura del Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, 2015), 120. Translated by the author. With Kidnappening, Minujín tried to recover Picasso’s shock value by literally bringing his work to life and breaking the boundaries of the picture frame as well as those of the institution itself. The Museum of Modern Art is not only an institution, but also the cathedral of modern art’s canonization. Minujín’s work thus denounced how the historical avant-gardes had become sterilized in the hands of museums. Perhaps then, as Minujín’s creative process advanced, she realized that the greatest homage she could pay to Picasso was not simply to bring his cubist characters to life, but rather to honor the king by laying siege to his castle—that is, the museum.

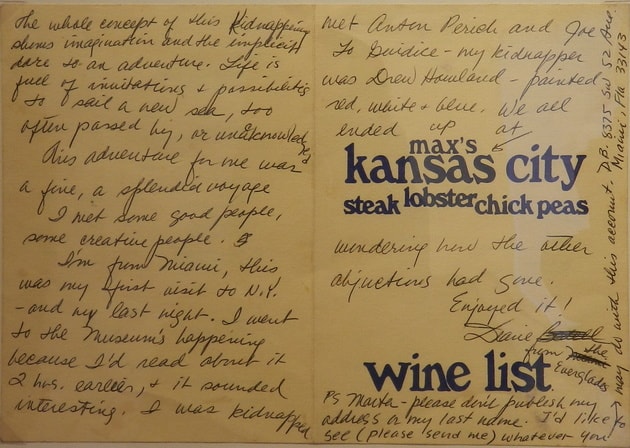

Many kidnapped participants were taken to the apartments and studies of Minujín’s friends, who had prepared dinners and decorated especially for the occasion.11Some spectators were taken by surprise. As Ty Castellan noted in his written testimony: “The event being somewhat dis-organized [sic] and crowded, they [some of the hostages] were chosen randomly [and at the last minute] from the audience. This created greater confrontation possibilities, another desirable element in the piece.” In Minujín, “Kidnappening.” One destination was the iconic restaurant and bar Max’s Kansas City, an underground arts hub since the 1950s.12See Steven Kasher, ed., Max’s Kansas City: Art, Glamour, Rock and Roll (New York: Abrams Image, 2010). Participants’ testimonies indicate that many, after being “abducted” and taken to a predetermined location, ended up going to Max’s Kansas City to celebrate. All of this points to another reading ofKidnappening: that of a social experiment in multitudes, communities, trust, and circles of belonging.13Probably the most beautiful story shared—and maybe also invented—by Minujín in her memoir was that of a young art student who, visiting New York from Chicago for the weekend, heard on TV about the performance and decided to attend. Curious but with no expectations, she happened to be among those kidnapped. She was taken to the photographer Anton Pelli’s studio, and the two fell in love at first sight and married soon after. Her testimony, as transcribed by Minujín, concludes romantically, “I wish all artists in the world were dedicated to crossing people’s destinies.” Minujín, “Kidnappening.”

To explore the social component of this work, we can compare it to the more famous and precedent-setting Minujín piece entitled Minucode, which was held in 1967 at the Center for Inter-American Relations. For this work, the artist announced four cocktail parties, each dedicated to a particular category of guests: businessmen, politicians, fashion-industry workers, and art-world habitués. These events were recorded and edited by Minujín, who then re-invited the guests to a film installation in a gallery space, where films of the parties were being screened.14For a detailed account of this work, see Alexander Alberro, “Media, Sculpture, Myth,” in A Principality of its Own: 40 Years of Visual Arts at the Americas Society, eds. José Luis Falconi and Gabriela Rangel (New York: Americas Society, 2006), 160–77. See also and especially Alexander Alberro, Inés Katzenstein, and Gabriela Rangel, Marta Minujín: Minucode(s) (New York: Americas Society, 2015). According to Alexander Alberro: “At one level, then, Minucode functioned as a ‘social-scientific environment.’ […] On another, the content of Minucode was the medium. Information was brushed against information.”15Alberro, “Media, Sculpture, Myth,” 165. Minujín thus challenged the role of the institution and its social interactions not only by creating these four parties but also by transforming them into a mirror-like installation in which people saw themselves in reflection.16As stated in the instructions sent to participants: “From the moment you enter the cocktail party, you become a part of the ‘invisible’ environment that is being filmed in order to become ‘visible.’ When you see the replay of your cocktail party, you will find that you are not part, but rather the sub-plot, of the social environment.” Statement from Marta Minujín and the administration of the Center for Inter-American Relations Art Gallery to all participants in Minucode, reproduced in Alberro, Katzenstein, and Rangel, Marta Minujín, 52.

Both Minucode and Kidnappening straddled the intersection between the inside and the outside of the art institution, introducing strong critiques of the traditional division between art and life. The participatory aspect of the performances highlighted this critique, emphasizing the role of community and social interaction in the politics of the art world(s). We see an interesting progression from one piece to the next. In Minucode, the outside world is incorporated into the museum, while in Kidnappening the museum is expanded into the outside world.

Last but not least, it is impossible not to read Kidnappening as a playful yet dead- serious reference to the real kidnappings then being carried out by paramilitary forces across Latin America, as well as to the infamous kidnappings of Patty Hearst and others in the United States. As one participant noted: “Since the Sixties [we have] witness[ed] a wave of hijackings, […] kidnappings of ambassadors, ‘states of siege,’ airline terminal snipers, Munich.”17“Participant Linda’s testimony,” Minujín, “Kidnappening.” The institutional critique inKidnappening must be read as a more expansive political commentary on normativity, violence, and the possibility of art to offer an escape, even if this exit comes through a violent act such as a kidnapping. The work dealt with the politics of the art world while simultaneously referencing political events from the real world and bringing them into the museum context.18In this regard, one could compare Minujín’s works with Graciela Carnevale’s Acción del Encierro (Confinement Action) whereby the artist locked visitors inside an art gallery forcing them to acknowledge and challenge their oppression by breaking their way out. This action was part of the Ciclo de Arte Experimental exhibition in Rosario organized by the Grupo de Arte de Vanguardia de Rosario in October 1968. Similarly, in July that same year, the Rosario artist group assaulted and interrupted a lecture by Jorge Romero Brest, art critic and director of the Centro de Artes Visuales [Center of Visual Arts] of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella. For more information on these experimental artistic actions, see: Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman, Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde”: vanguardia artística y política en el 68 argentino (Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 2008); Ana Longoni, Vanguardia y revolución: arte e izquierdas en la Argentina de los sesenta-setenta (Buenos Aires: Ariel, 2014.); and Andrea Giunta, Avant-Garde, Internationalism, and Politics: Argentine Art in the Sixties, trans. Peter Kahn (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007). Perhaps Minujín was also trying to show that society as a whole can suffer from a sort of Stockholm syndrome, finding sympathy and attachment in the violence it experiences. However, from another perspective, we may also wonder about the cynical aspect of staging violence at such an upscale event as a museum party. As noted by the same participant, the work played with “a psychology that sought excitement and novelty without any real threat of danger […] the chic mentality seeks to cash in on such vicarious danger without any real threat of danger.”19Ibid.

Critical while at the same time purposely banal, Kidnappening forced participants to experience social and institutional violence in a playful yet highly acute simulacrum. Interestingly, it was only at a distance from her home country, and in experimenting with the boundaries between the inside and outside of the New York art world, that Minujín could offer such a prophetic and incisive work about the violence then roiling the American continent.20A version of this article was presented at the 2017 Institute of Fine Arts / Frick Symposium in art history. Special thanks to MoMA Archives staff and to Henrique Faria Fine Art for their generous collaboration, and to Marta Minujín for her spirit and inspiration.

- 1Robert Shepard, “GOING OUT Guide,” New York Times, August 3, [1973], 16.

- 2The Summergarden program was sponsored by Mobil, and since 1971, offered free late-night weekend events during the summer in which a wide range of spectacles including music, dance, jazz, Egyptian belly dance and mimes were presented. According to MoMA’s records, that summer the program received a daily attendance of 1,200 people, with a season total of 56,000. For her August 3 and 4 performances, Marta received a budget of $400, with the rest needed coming from “the impossible or the miraculous.” Marta Minujín, “Kidnappening,” in “Kidnappening Folder,” n.d. Courtesy of the artist and Henrique Faria Fine Art. Translated from Spanish by the author.

- 3“I would take the cubist period, in particular ‘The mademoiselles d’Avignon.’” Marta Minujín, ibid.

- 4Marta Minujín, “Picappening, Picassening, Picassonning,” in Minujín, “Kidnappening Folder.”

- 5The lyrics to be sung and screamed by the performers in this “opera-cantata-happening” were selected by Minujín with the help of Claudio Bedel, a Chilean poet who lived in New York City. In addition to many quotes from Picasso, there were lines from Cézanne, Renoir, Matisse, Derain, Braque, Brancusi, Duchamp, and the “Manifesto of Futurism” by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. The performers also repeated lines from thinkers such as Plato and even Mao Tse-Tung. From the latter, Minujín included: “When you do anything, unless you understand its actual circumstances, its nature, and its relations to other things, you will not know the laws governing it, or know how to do it, or be able to do it well.” Mao Tse-Tung, “Problems of Strategy in China’s Revolutionary War” (December 1936), in Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung. Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1:179. Interestingly, something similar could be said of Kidnappening. The work cannot be understood without paying attention to its actual circumstances—i.e., the museum setting—or to “its relations to other things,” such as the surrounding city and cast of characters.

- 6In 1967, with Kaprow and the artist Wolf Vostell, Minujín created the first international Happening, A 3 Country Happening. See Michael Kirby, “Marta Minujin’s ‘Simultaneity in Simultaneity,’”Drama Review: TDR 12, no. 3 (1968): 149–52; and Victoria Noorthoorn, ed., Marta Minujín: Obras 1959–1989 (Buenos Aires: Malba-Fundación Constantini, 2010), 74–75.

- 7For more on Minujín’s place in between categories and Oscar Massota’s reading of her work, see Catherine Spencer, “Performing Pop: Marta Minujín and the ‘Argentine Image-Makers,’” Tate Papers, no. 2 (Autumn 2015), http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/24/performing-pop-marta-minujín-and-the-argentine- image-makers, accessed April 18, 2017.

- 8“Art Event Staged by Marta Minujin in Museum Garden,” press release no. 96 (August 1972), The Museum of Modern Art Press Release Archives, New York, https://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/pressarchives/4877/releases/MOMA1972010696.pdf?2010, accessed September 10, 2017.

- 9Marta Minujín, “Kidnappening.” As Minujín detailed in a manuscript written shortly after the performance, the work would be an “opera, because in some moments arias would be sung, cantata because there would be many choruses, and happening, because at the end something really unexpected would happen, an overflow of incidentals.” In this new, mixed genre, the use of intermission and interruption as a concept behind Interpenningwas taken one step further to make the whole event a disruption.

- 10Marta Minujín, untitled article, La Nación, October 25, 1981. Cited in Marta Minujin: Happenings y Performances(Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Cultura del Gobierno de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, 2015), 120. Translated by the author.

- 11Some spectators were taken by surprise. As Ty Castellan noted in his written testimony: “The event being somewhat dis-organized [sic] and crowded, they [some of the hostages] were chosen randomly [and at the last minute] from the audience. This created greater confrontation possibilities, another desirable element in the piece.” In Minujín, “Kidnappening.”

- 12See Steven Kasher, ed., Max’s Kansas City: Art, Glamour, Rock and Roll (New York: Abrams Image, 2010).

- 13Probably the most beautiful story shared—and maybe also invented—by Minujín in her memoir was that of a young art student who, visiting New York from Chicago for the weekend, heard on TV about the performance and decided to attend. Curious but with no expectations, she happened to be among those kidnapped. She was taken to the photographer Anton Pelli’s studio, and the two fell in love at first sight and married soon after. Her testimony, as transcribed by Minujín, concludes romantically, “I wish all artists in the world were dedicated to crossing people’s destinies.” Minujín, “Kidnappening.”

- 14For a detailed account of this work, see Alexander Alberro, “Media, Sculpture, Myth,” in A Principality of its Own: 40 Years of Visual Arts at the Americas Society, eds. José Luis Falconi and Gabriela Rangel (New York: Americas Society, 2006), 160–77. See also and especially Alexander Alberro, Inés Katzenstein, and Gabriela Rangel, Marta Minujín: Minucode(s) (New York: Americas Society, 2015).

- 15Alberro, “Media, Sculpture, Myth,” 165.

- 16As stated in the instructions sent to participants: “From the moment you enter the cocktail party, you become a part of the ‘invisible’ environment that is being filmed in order to become ‘visible.’ When you see the replay of your cocktail party, you will find that you are not part, but rather the sub-plot, of the social environment.” Statement from Marta Minujín and the administration of the Center for Inter-American Relations Art Gallery to all participants in Minucode, reproduced in Alberro, Katzenstein, and Rangel, Marta Minujín, 52.

- 17“Participant Linda’s testimony,” Minujín, “Kidnappening.”

- 18In this regard, one could compare Minujín’s works with Graciela Carnevale’s Acción del Encierro (Confinement Action) whereby the artist locked visitors inside an art gallery forcing them to acknowledge and challenge their oppression by breaking their way out. This action was part of the Ciclo de Arte Experimental exhibition in Rosario organized by the Grupo de Arte de Vanguardia de Rosario in October 1968. Similarly, in July that same year, the Rosario artist group assaulted and interrupted a lecture by Jorge Romero Brest, art critic and director of the Centro de Artes Visuales [Center of Visual Arts] of the Instituto Torcuato Di Tella. For more information on these experimental artistic actions, see: Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman, Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde”: vanguardia artística y política en el 68 argentino (Buenos Aires: Eudeba, 2008); Ana Longoni, Vanguardia y revolución: arte e izquierdas en la Argentina de los sesenta-setenta (Buenos Aires: Ariel, 2014.); and Andrea Giunta, Avant-Garde, Internationalism, and Politics: Argentine Art in the Sixties, trans. Peter Kahn (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).

- 19Ibid.

- 20A version of this article was presented at the 2017 Institute of Fine Arts / Frick Symposium in art history. Special thanks to MoMA Archives staff and to Henrique Faria Fine Art for their generous collaboration, and to Marta Minujín for her spirit and inspiration.