Bringing together multiple testimonies and reflections related to the history and legacy of the textile community of Tomé, LA FÁBRICA. Trazado de una investigación is an artistic-curatorial project initiated by the artist Claudia del Fierro and the curator Ana María Saavedra in 2016. In this text, Leticia Gutierrez provides a brief historical background of this community, and discusses how the project LA FÁBRICA promotes citizen mobilization and contributes to the social and political dialogue of a community that actively chooses what to remember.

Read the Spanish version here.

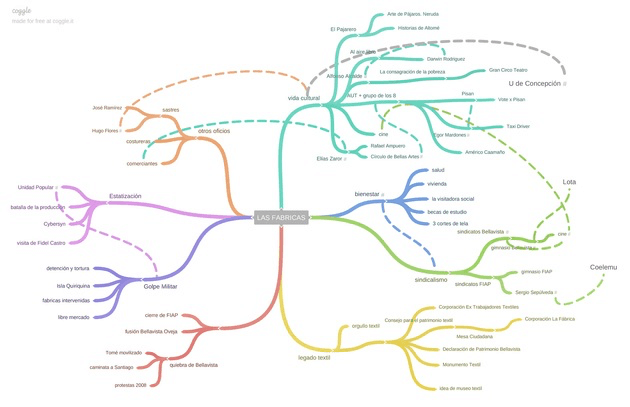

Since 2016, artist Claudia del Fierro and curator Ana María Saavedra have investigated the textile history of the city of Tomé1Tomé is a city located in the province of Concepción, in the Biobío region of central Chile. through an editorial and exhibition project entitled LA FÁBRICA. Trazado de una investigación (THE FACTORY: Layout of an Investigation). Their project brings together the voices of members of the textile community of Tomé—former employees, their families and neighbors, as well as academics and journalists—with the purpose of forming a collection of oral histories and practical studies that, in a unified testimony, ensures the right of the community to defend its history and preserve its buildings. The methodology of the project includes an ongoing work of art that operates within the social and political dialogues of a community that actively chooses what to remember. LA FÁBRICA uses art as a tool for citizen mobilization and social responsibility, thus benefiting the community by contributing to the construction of its heritable memory.

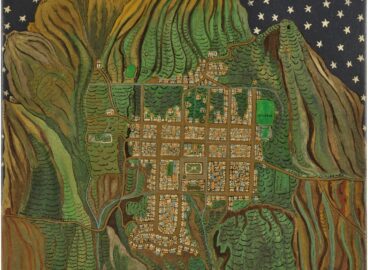

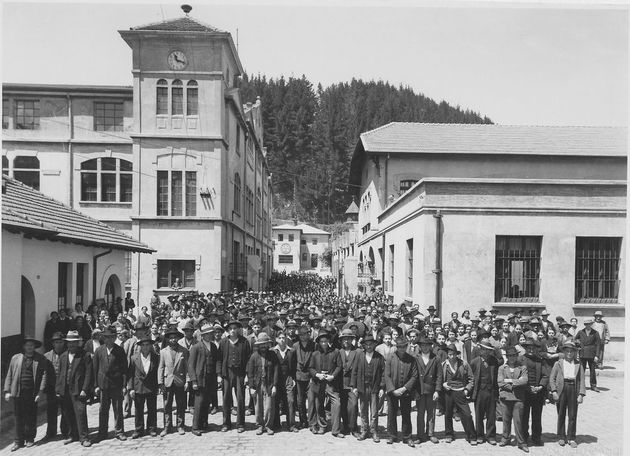

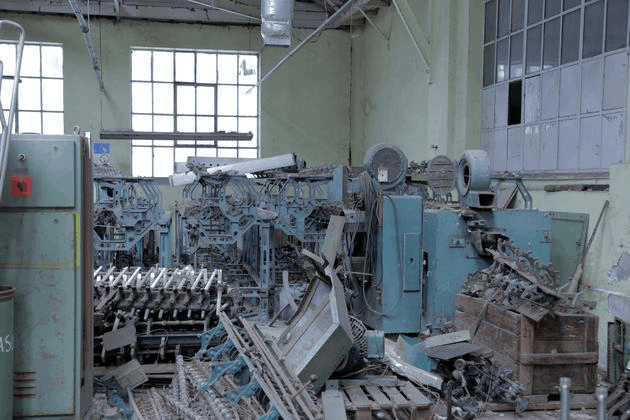

The history of the textile community of Tomé began in 1865 with the founding of Bellavista Oveja Tomé. After the factory’s opening, and in the years that followed, residences for the company’s workers were built around it, as were other textile factories, a church, a market, a school, and a gym.2“Bellavista Oveja Tomé: La marca que tejió la moda chilena,” Revista Ya, December 11, 2007. Because of the high quality and export value of its wool, Tomé became the birthplace of one of the main textile industries in Latin America in the 1950s and 1960s. However, though a profitable company of great wealth, Bellavista Oveja Tomé was nonetheless affected by the 1982 financial crisis, which took place in Chile during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, between 1973 and 1990, and was attributed to the overvaluation of the Chilean peso and the country’s high interest rates.3Gabriel Salazar and Julio Pinto, Historia contemporánea de Chile, vol. 3, La economía: mercados, empresarios y trabajadores (Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 2002). Despite various attempts to recover, Bellavista Oveja Tomé was forced to declare bankruptcy definitively in 2008, leaving behind more than 100 years of history and negatively impacting the viability of the textile operation in Tomé.

In order to preserve the textile factory buildings, including Bellavista Oveja Tomé, and their history, in 2014, residents and community organizations formed the Mesa Ciudadana por el Patrimonio de Tomé (Citizens’ Committee for the Tomé Patrimony), which, in 2016, succeeded in having the Bellavista Oveja Tomé factory declared a National Historic Monument. This declaration—in which the Citizens’ Committee was constituted as the cooperative Corporación La Fábrica (La Fábrica Corporation) in 2017—protects and regulates use of the factory’s property, prohibiting its demolition or its use for purposes other than cultural ones. This dictate essentially prevents the site from becoming a commercial venue, which would contribute to urban shifts such as gentrification.

LA FÁBRICA as an artistic-curatorial project was articulated in a 2017 publication and accompanied by two exhibitions: one held in 2017 at Centro Cultural Tomé (Tomé Cultural Center) in the city of Concepción, and another to be held in 2019 at Galería Metropolitana (Metropolitan Gallery) in the Pedro Aguirre Cerda in Santiago District. The publication brings together the written and graphic contributions of anthropologist Christian Matus Madrid, architect Nicolás Sáez, journalist Carolina Lara, researcher and neighbor Daniel Cartes Binimelis, as well as Claudia del Fierro and Ana María Saavedra. The exhibition at Centro Cultural Tomé comprised artwork and archival materials that touched on topics such as cultural life, well-being, trade unionism, textile pride, military coups, Bellavista’s bankruptcy, and other trades. The exhibition’s central piece was a video documenting the testimonies of former workers and other agents linked to the factories buildings. The exhibition at Galería Metropolitana is still being planned, but as of now, the work’s aim is to extend the funds for patrimonial preservation of the factory’s buildings.4The data on the extension of State funds was provided during an interview with Claudia del Fierro and Ana María Saavedra conducted by Leticia Gutiérrez, July 31, 2018, via video call.

According to del Fierro and Saavedra the credit for the declaration of the Bellavista Oveja Tomé factory as a National Historic Monument should be given to the Citizens’ Committee.5Ibid. However, the artistic-curatorial project LA FÁBRICA cannot be separated from the efforts of La Fábrica Corporation. The publication and first exhibition drew the attention of the citizens of Tomé to the subject, and contributed directly to the discussion and ensuing initiative to preserve the textile factory. Such was the case for Matus Madrid, who is part of the Citizens’ Committee, and who contributed to LA FÁBRICA through a reflection on the notion of cultural heritage. Matus Madrid points out that goods declared as heritage do not obey a mere commercial and economic value, since the assets would run the risk of becoming a fetish. The historical value of the goods are tied up not only in the factory buildings, but also in the memory of the textile industry—in its polyphonic and personal history—and in the affective relationship between the material and the immaterial. Examples of the diverse stories, both academic and more sentimental, are contained in the 2017 publication. In her contribution, Carolina Lara provides a brief history of the formation of artists unions and of cultural activities, both before, during, and after the Pinochet dictatorship. For his part, Nicolás Sáez contributes a chronicle of photography and horticultural workshops that explore topics including the function of creating images and the planting of medicinal plants and fruit trees. Lastly, Daniel Cartes Binimelis, who is part of the Citizens’ Committee, suggests the construction of a museum for the community of Tomé—a museum imagined thanks to the exhibition curated by Saavedra and del Fierro.

These are some examples of the ways in which LA FÁBRICA has been inserted into the dialogue taking place within the community and impacted the heritage negotiations and the collective conscience. The gathering of community perspectives and their visibility through both the publication and the exhibition mobilized citizens to achieve the declaration of patrimony. This represents the right of the community to determine what of its history is to be preserved—and thus its own legacy—which in turn is constitutionally protected by the State through the declaration of patrimony.

As a methodology, LA FÁBRICA emphasizes the openness of its study process, which is also open-ended, and identifies future topics of interest, such as the role of women in the community. This material, according to Saavedra, is in a state of “development” and forms part of “a guided-for-practice creative research.”6Claudia del Fierro and Ana María Saavedra, eds., LA FÁBRICA. Trazado de una investigación(Concepción: Trama Impresores SA, 2017), 6.

The research method behind the project is also related to the curatorial work that Saavedra and art historian Luis Alarcón have carried out as co-directors of Galería Metropolitana. Although LA FÁBRICA is not a project intrinsically conceived within Galería Metropolitana, its association with the values that Galería Metropolitana represents is undeniable. From the choice of topics to be investigated to the overall development and scope of the project, the methodology undertaken is based on the curatorial axes that Saavedra and Alarcón exercise through Galería Metropolitana.

Galería Metropolitana has functioned since 1998 as a space that seeks to contribute to systems of social participation. Saavedra and Alarcón seek to create projects from “zones of dispute,” or “conceptual zones of conflict,” as models of action for the social transformation of institutions.7Quotes taken from an interview with Ana María Saavedra and Luis Alarcón conducted by the author in Santiago de Chile, Galería Metropolitana, June 2, 2018. The curator assumes a role of articulator, mobilizing artistic practice in a public way and collaborating with networks inside and outside of the art system to promote common values and benefits:

As the network of Latin American and international articulations in which Galería Metropolitana moves, L. Alarcón and A. M. Saavedra have trespassed evermore borders (between what is local and global, but also, between what is within the art-system and its communal outskirts) and therefore, have deployed the mobility of speaking several languages simultaneously: the language of the institutional pact and the eventual negotiation of interests, of the reconversion and the detour of symbolic-cultural resources for alternative means to the ones that controlled their economic sources, of the infiltrations of the authority system through almost invisible cracks that end up eroding their consensus bases.8Luis Alarcón and Ana María Saavedra, eds., Galería Metropolitana 2011–2017 (Santiago de Chile: Andros, 2017), 29. Translated from the original by the author.

As cultural theorist Nelly Richard states, the cultural management of Galería Metropolitana has been responsible for generating interest in reconsidering the place and function of art by placing the creative practice into tension with the political, economic, and social systems of democracy. Its curatorial practice transcends the art world, seeking to use the art system as a system of collaboration that aims for the common good.

In relation to LA FÁBRICA, the curatorial practice enables art to transcend mere contemplation and its fetishization, and to exist within a framework of conflict zones. The project maps different layers and contradictions in the creative practice, encouraging its audience to think differently about what art can achieve, and making art useful as a tool for citizen participation. The zones of dispute and conflict from which the project operates are the governance of the declaration of patrimony and the desire to preserve the textile history of Tomé. The institutional transformation lies in giving visibility to the stories of the community as a strategy to activate zones of cultural democracy. That is, citizens exercise the right to defend their interests; they appear before the state authority to intercede on behalf of the case they have chosen to represent, and the history they have chosen to represent themselves and that will be inherited by future generations.

In this way, through art and curatorship, this initiative affects politics. It is from the collaboration, a critical discourse, and a self-reflective enunciation, that LA FÁBRICA. Trazado de una investigación encourages citizen mobilization and can be seen as a strategy for institutional transformation and political exercise.

Translated from Spanish by Silvina López Medin.

- 1Tomé is a city located in the province of Concepción, in the Biobío region of central Chile.

- 2“Bellavista Oveja Tomé: La marca que tejió la moda chilena,” Revista Ya, December 11, 2007.

- 3Gabriel Salazar and Julio Pinto, Historia contemporánea de Chile, vol. 3, La economía: mercados, empresarios y trabajadores (Santiago: LOM Ediciones, 2002).

- 4The data on the extension of State funds was provided during an interview with Claudia del Fierro and Ana María Saavedra conducted by Leticia Gutiérrez, July 31, 2018, via video call.

- 5Ibid.

- 6Claudia del Fierro and Ana María Saavedra, eds., LA FÁBRICA. Trazado de una investigación(Concepción: Trama Impresores SA, 2017), 6.

- 7Quotes taken from an interview with Ana María Saavedra and Luis Alarcón conducted by the author in Santiago de Chile, Galería Metropolitana, June 2, 2018.

- 8Luis Alarcón and Ana María Saavedra, eds., Galería Metropolitana 2011–2017 (Santiago de Chile: Andros, 2017), 29. Translated from the original by the author.