Since the late nineties, the work of Regina José Galindo has been characterized for denouncing different forms of oppression and violence in contemporary society. One recurring theme in her artistic career has been the migratory mobilizations and displacement of Central Americans as a result of the civil wars that took place in Guatemala and other countries of the region in the 1970s. Focusing on Galindo’s America’s Family Prison (2008), Rossina Cazali analyzes how the artist approaches the different power relations (the legal and illegal), and the mechanisms of negotiation and multiple complicities that define the complex panorama of contemporary migrations between Central America and the United States.

Read the Spanish version here.

The desert is a natural extension of the inner silence of the body. If humanity’s language, technology, and buildings are an extension of its constructive faculties, the desert alone is an extension of its capacity for absence, the ideal schema of humanity’s disappearance. —Jean Baudrillard1Jean Baudrillard, America, trans. Chris Turner (London: Verso, 1988).

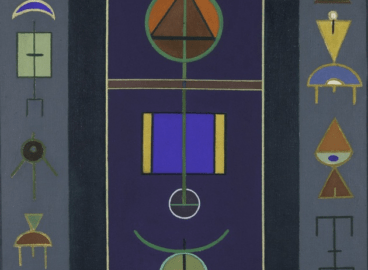

A reference point for performance art in Latin America, Regina José Galindo (born 1974) has gotten us used to thinking of her own body as a catalyst of a territory where living matter and waste (water, blood, earth, among others things) create a symbolic and generally violent space. However, in America’s Family Prison (2008), she deliberately introduces an object that allows the audience to explore, in a metaphoric sense, the complicated landscape of contemporary migration—from the effects of the policies and forms of control adopted by the governments of both transit and destination countries, to the vast range of cultural, racial, and economic stereotypes that dominate these territories. The object consists of a small cube-shaped cell used to hold people detained by the authorities in their attempt to cross the border between Mexico and the United States. Aseptic and intimidating in appearance, this cubicle is mounted on a platform, which gives it a sculptural dimension within the gallery space. This example is but one of the thousands of such portable cells that specialized companies produce for the temporary detention of people involved in criminal cases in the United States, particularly illegal immigrants awaiting resolution of their immigration status.

As a first impulse, the lonely image of the small cell evokes the Dadaist gesture—perhaps in a romantic way—of the readymades that became the foundations of avant-garde art in the early twentieth century. Certain features recall the artistic tradition of non-objectual art introduced by Peruvian art critic Juan Acha (1916—1995) in the eighties.2In his seminal essay “Non-Objectualist Theory and Practice in Latin America,” first presented in the context of the First Latin American Conference on Non-Objectualist Art and Urban Art hosted by Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín in May 1981, Juan Acha talked about non-objectualist art practices in Latin America, addressing in particular the processes of signification involved in the development of non-objectualist works of art in the continent. According to Acha, there was a sensitive transfer of social languages delimited by the factors of class and cultural context. The “artistic reality” to which Acha referred emerged from the specificities of social, political, and economical environments of Latin American prospects, providing the non-objectualist work with a particular approach of its aesthetic reflections. See “Non-Objectualist Theory and Practice in Latin America,” post, Museum of Modern Art, https://post.at.moma.org/sources/31/publications/288. For more on the subject, see also Proceedings of the First Latin American Conference on Non-Objectualist Art and Urban Art (Medellín: Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, Museo de Antioquia, 2010). However, these associations fall short in regards to the radical nature and relevance of the social, ethical, and political critique that America’s Family Prison represents. The elements that make up the piece—the action itself, the resulting video, the setting up of the small cell as a sculptural object, and the documentary photos—evoke the troubled framework of relationships woven over time between the United States and the governments of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, the three countries known as the Northern Triangle of Central America, extend to the caravan of thousands of migrants that formed in Honduras in October 2018 and headed toward the United States. In the news coverage, this image of mass flight vacillated between a depiction of a threatening otherness and the legitimate exodus of people fleeing violence and a lack of opportunities. As the artist once said of Guatemala, “A peace treaty may have been signed, but the weapons and the social conflicts continue.”3Marjan Terpstra, “Regina José Galindo: Guatemala Is Violent and so Is My Art,” The Power of Culture (blog), May 2018, http://www.powerofculture.nl/en/current/2008/May/galindo.html.

The action that animates America’s Family Prison came about as part of a commission Galindo received through Artpace’s International Artist-in-Residence program in San Antonio, Texas. This context is, undoubtedly, an essential frame of reference. As a resident artist, Galindo began to thoroughly research San Antonio and its position as a border town. The location allowed her to reflect on the different roles and power relations within the region, between the legal and the illegal, between the mechanisms for negotiation and the multiple complicities that define a political border.4San Antonio is one of the busiest hubs for undocumented aliens seeking to enter the United States. The San Antonio Border Patrol Station, which opened for operations in September 1988, is responsible for a total geographical area of approximately 18,000 square miles. Because of their numerous industrial centers, support services, and construction companies, Austin, which is the state capital, and San Antonio, attract thousands of undocumented aliens every year. The Union Pacific Railroad runs trains from the south and from the west that pass through the area, and these are frequently used as free transportation by migrants and illegal aliens.

The coordinates are clear: while the prison cell, positioned as a work of art in the center of a gallery at Artpace, invites discussion of the problem of exhibiting an object devoid of features worthy of museum display, above all, it primes the audience and speaks to an entire society that has allowed the regulation, criminalization, and commercialization of ways of life emerging from contexts marked by lack of protection and by inequality and injustice.

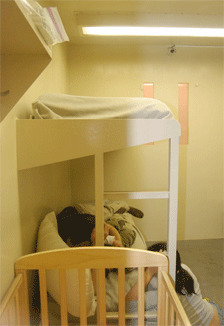

As an industrial product, the cubicle is somehow beautiful. It stands in silence, suggesting the possibility of a hushed dialogue with the minimalist pieces on display at the Chinati Foundation, six hours from Austin, in Marfa, a city in the high desert.5The Chinati Foundation is a contemporary art museum located in Marfa, Texas. Its founder, the artist Donald Judd, began planning it in 1978 with financial support from the Dia Art Foundation. Based on Judd’s ideas of combining art, architecture, and nature, the foundation centered on exhibiting minimalist works by artists such as John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin, and Judd himself. It opened to the public in 1986. Since then, the collection has incorporated works by other artists, including Carl Andre, Ingólfur Arnarsson, Ilya Kabakov, Richard Long, Roni Horn, and Claes Oldenburg, among others. The object itself questions the forms of power connected to and depicted through its mass-produced architecture, and the industry linked to the prison system in its starkest versions. However, this narrative begins to come apart the moment the viewer goes up to the platform and peeks through the narrow window in the object’s sole door. This action—defined by the institutional and artistic setting—breaks a first invisible barrier. As viewers look into the interior of the cubicle, they run their eyes over the results of years of specialization in the design and construction of tools and devices for the prison and detention industry. These assorted components, made of industrial materials, include an unbreakable mirror, a steel sink-and-toilet combo, other plumbing fixtures, lamps, and wall-mounted bunks, a stool, and a desk. Grilles, locks, and ironwork are integrated into the room as complements—and in order to prevent escape attempts.6See Sweeper Metal Fabricators Corp. website, http://www.sweepermetal.com/products/modular-steel-cells/.

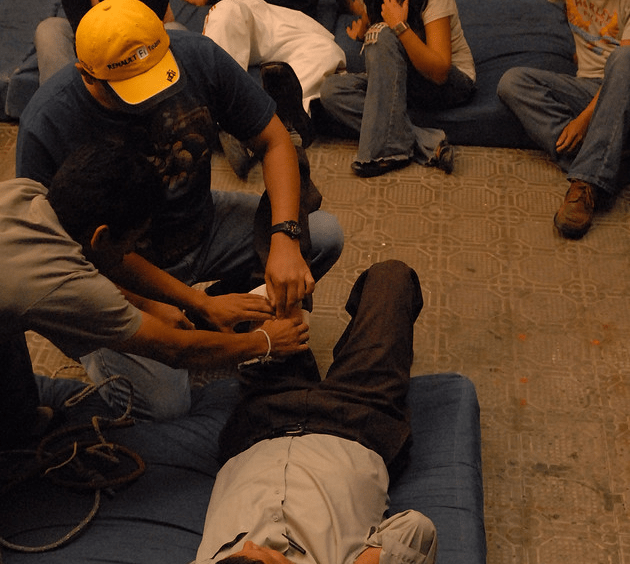

Considering the ways that her audience might connect with the small cell, Galindo began her performance by renting one for the two-month duration of the exhibit. In addition to paying $8,000 to a specialized manufacturer in Oklahoma, the artist—with the support of Artpace–offered to move and adequately install the object, with the purpose of promoting the cell and attracting potential clients in the San Antonio area. The second part of the performance consisted of inhabiting the cell, once it was installed in the gallery, with her husband and young daughter for thirty-six hours. The purpose was to show, in a cold, efficient way, how the cell functioned. Analogous to a model home presented in a housing fair, this prototype cell transformed the Artpace gallery into a temporary shop window intended to attract those interested in the private business of family cells. Viewers could approach the window in order to observe the cell’s interior and the movements of the artist and her companions within it. As if that was not enough, the look and gestures of the external observers functioned as panoptic view. Temporarily, they assumed the role of prison wardens in order to observe and, in a way, control the artist and her family. The video that registers all of these movements—both internal and external—remains as evidence of a particular means of control and as a relentless reference point in our contemporary society riddled with technologies and cameras that, in border areas, airports, and customs offices, collude with the efficient systematization of verification, inspection, and control of any potential source of threat to US national security.

In constructing an overview of migratory dynamics, as seen from the perspective of the United States, one cannot disregard Americans’ historical need to reconfirm their identity, culture, and national borders against a threatening otherness. On the political level, these dynamics are also affected by the inability of the US government to crystallize economic strategies, development plans, or definitions of policies with their neighbors in the sphere of immigration. However, the discussion opened by Galindo’s work suggests that it is the legal dimension that best reflects the American anti-immigrant spirit. In that sense, it is helpful to go back to some ideas from Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) by the French philosopher and theorist Michel Foucault (1926—1984). In this emblematic book, Foucault traces, in a fascinating way, the different points that led to the consolidation of the idea that there is no imprisonment outside the law. In the words of Foucault, there is “no detention that had not been decided by a qualified judicial institution.”7Michel Foucault, “The Carceral,” in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 277. Following this logic, the prison systems evolve only toward models that are free of arbitrariness and subject to a legal framework. However, from Galindo’s critical point of view, extra-penal forms of imprisonment have never been dismantled; rather, they have been reactivated and reorganized in order to legitimize inhumane policies such as the separation of migrant families,8In 2018, the Trump administration instituted a hard-line immigration policy, under which more than 200 children were separated from their families as they were illegally crossing the border between Mexico and the United States. These separations occurred at the same time as a massive influx of families, most of them coming from the Northern Triangle of Central America. The Trump administration policy failed in its objective to discourage the migrants from traveling and was rescinded nine months later. For a summary of the situation, see Miriam Jordan and Caitlin Dickerson, “US Continues to Separate Migrant Families Despite Rollback of Policy,” New York Times, March, 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/09/us/migrant-family-separations-border.html. and the functioning of perverse industries such as the one exposed by America’s Family Prison. With all the legal apparatus in its favor, the current prison industry emerged in the United States in the early eighties and subsequently flourished alongside the hardening of immigration and anti-terrorism laws. Later on, it came to play a prominent and extremely lucrative role in immigrant services and the arrests market. Since Barack Obama’s administration (2009–17), these prisons, generally made up of mobile cells installed on rented properties, have been authorized by the state to lodge whole families, usually immigrants awaiting resolution of their immigration status. However, as time has passed, the situation has become unsustainable as multiple human rights organizations have begun reporting on their practices of exploitation and degradation of detained people.

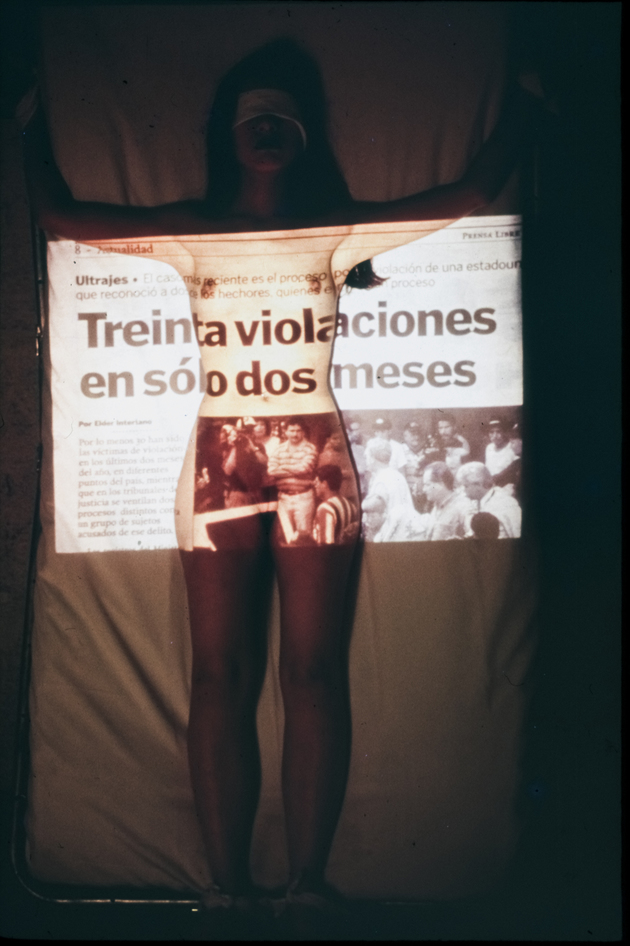

No doubt, Galindo’s artistic career has been fueled by discussions of topics so vital and contemporary as migration. However, it would be hard to understand her work’s poetic essence and lucid radicality without considering the context from which it emerged. Galindo’s artistic work began to find a place in the complex and nonexistent field of performance art in the late nineties in Guatemala, right from her first public performance entitled El dolor en un pañuelo (The Pain in a Handkerchief; 1999). Naked and tied to a bed in an upright position, she had newspaper clippings of the countless stories of rape and abuse carried out against women in Guatemala in those years projected onto her body. Ironically, the country was beginning a postwar period marked by the signing of peace accords in 1996. “Postwar,” however, did not mean an immediate cease-fire. In Guatemala, the idea of “postwar” has implied a recycling process of the legacy of violence, corruption, authoritarianism, and social trauma left to the country by the internal armed conflict. This conflict began with a coup d’état and the overthrow of president Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (1913—1971), which interrupted the democratic period known as the October Revolution (1944—54).9The October Revolution or 1944 Revolution was the civic movement that ended an era of dictatorships and marked a turning point in the history of the country, beginning 10 years of democratic, cultural, and institutional advances that endure today. During this period, the country was governed by a revolutionary junta and two democratically elected presidents: Juan José Arévalo (president from 1945 to 1951) and Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (president from 1951 to 1954). In 1954, in the context of the Cold War, the National Liberation Movement, led by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas with the support of the US Department of State and the CIA, attacked several villages in Guatemala, by air and land. This armed invasion, popularly known as the counterrevolution, ended the revolutionary period and forced President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán to resign on June 27, 1954. But its counterinsurgent military dimension, as a state policy, began in 1960 in the context of the Cold War, just when ideological tensions were worsening throughout the world.

Three generations of artists were affected by the political and social problems during those years, resulting in a long tradition of political art. As part of the next generation of Guatemalan creators, Galindo and her peers, not having experienced the conflict in a direct way, have focused on exploring the effects of war on a subjective level, recognizing it as social trauma. This generation was the first to recognize and take up the potential of Guatemala City’s historic center as a favorable setting to examine the collective subjectivity and to elaborate new discursive forms. As in other countries on the continent, in those years, public spaces came to be the nerve center of expressions of street art and festivals that took place in urban settings and were focused on performance art. In this framework, Galindo quickly adopted performance art as a way of amplifying her voice and her criticism. Her naked body was, in the beginning, the image that succeeded in capturing all of the attention for her unusual forms of protest. It was her operating center and her canvas. The artist managed to remove any eroticizing possibility from her body by thinking of it—and presenting it—as a territory on which complex cultural signs converge, and from which the artist appealed to the bodies of women in the plural. In different works, Galindo has drawn on the events of the internal armed conflict in Guatemala in order to define women’s bodies as inescapable aspects of the spoils of war. The multiple rapes of women carried out during the massacres of indigenous peoples—mainly from the Altiplano—in the eighties, with the purpose of destroying family lineages was one of the preferred strategies of the counterinsurgency during the genocide that took place in the Central American country.

From a position of unwavering commitment to the history and memory of her country, Galindo makes use of her deep knowledge of the political and social events that have marked Guatemalan society for the last decades. One of them is the troubled universe of migratory movements and the history of Central American people fleeing toward the north, movements that began in the seventies as a direct effect of civil war, particularly the ones in Guatemala and El Salvador. In the eighties, the systematic, planned dismantling—as a military objective—of the farming and agricultural peasant communities, permanently shifted the migratory pattern to a massive illegal flow. Between the nineties and the early two thousands, in the context of the region’s peacemaking agreements and treaties, clandestine migration reached alarming levels. And yet, this situation remained largely invisible and unknown to the rest of the world.

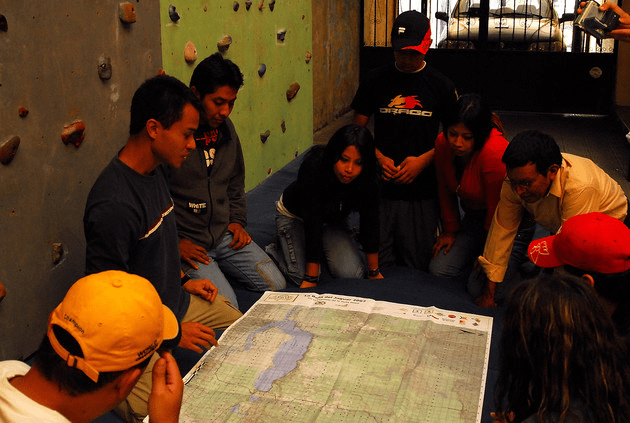

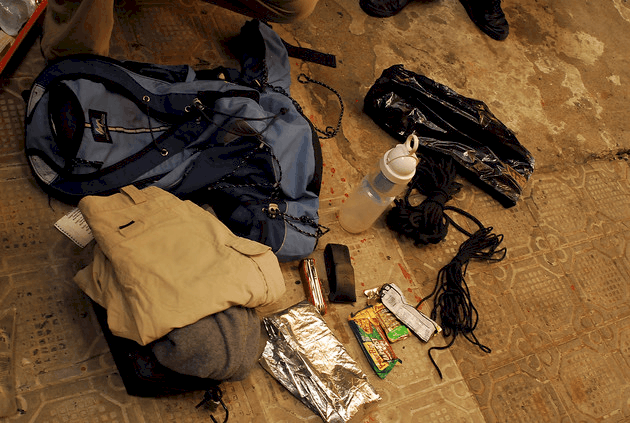

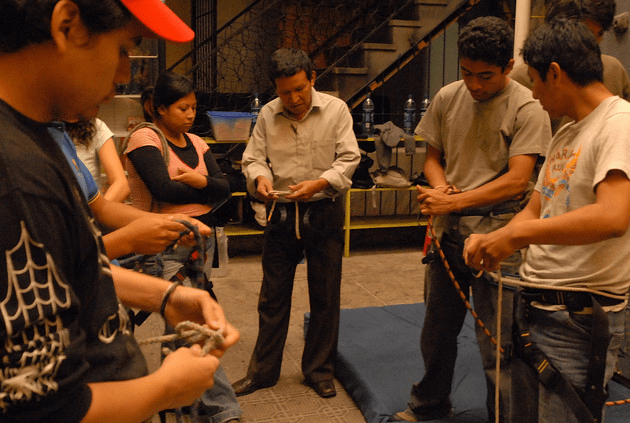

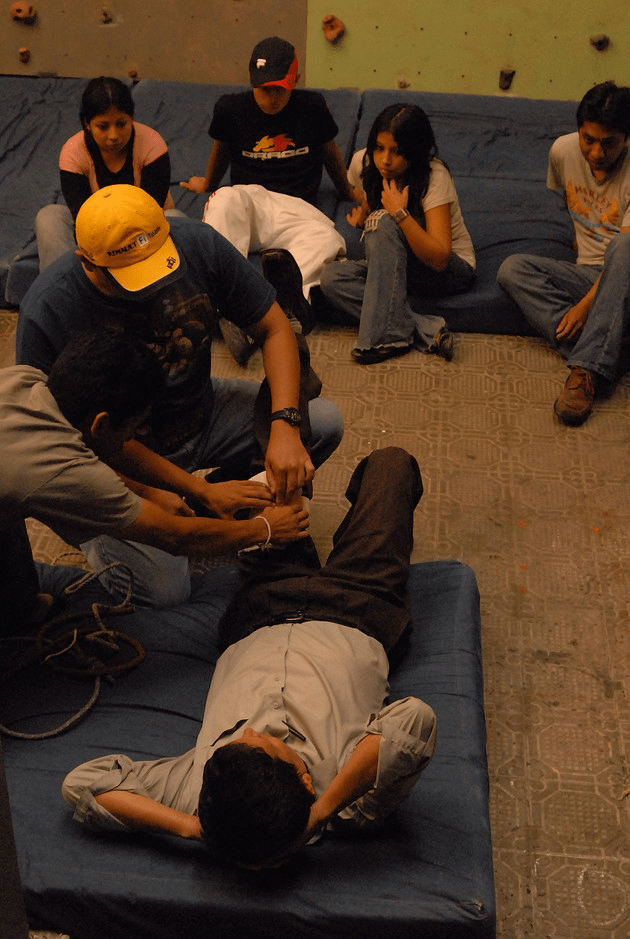

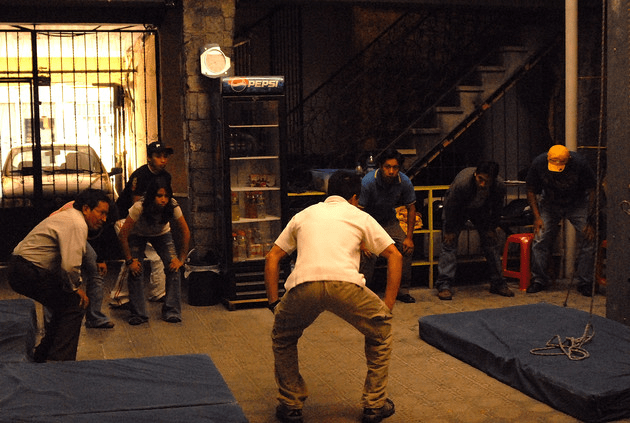

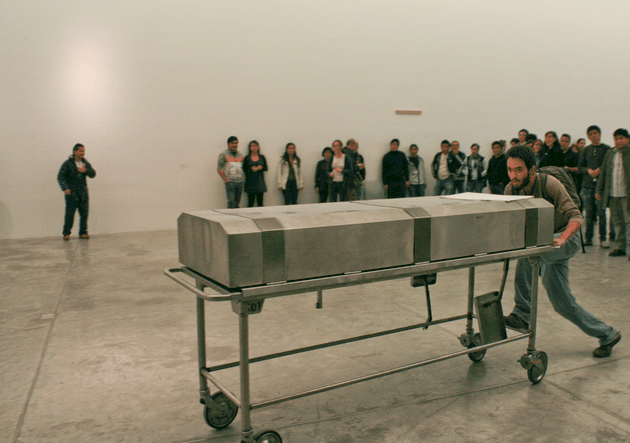

As part of that vast genealogy of Central American migrations, America’s Family Prison is one of several works the artist has developed around this theme. Her artistic and political stance on a subject of immeasurable dimensions has generated works such as Curso de supervivencia para hombres y mujeres que viajarán de manera ilegal a los Estados Unidos (Survival Course for Men and Women Traveling Illegally to the United States; 2007), which explored the subject in a straightforward manner by creating a space that was extremely useful to future migrants, where they could learn to face the obstacles and situations—from the extreme to the ordinary—that might come up during their journey. In a more metaphorical sense, Let’s Rodeo(2008), also performed at Artpace, was comprised of the action of climbing onto a mechanical bull, again and again, over the course of one and a half hours, with the sole purpose of taming the untamable. Móvil (Mobile; 2010), commissioned and produced by the Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City, addressed the problem of drug trafficking between the north and south. The starting point of this work was an action in which the artist lay inside a dead body cart. The audience was then invited to randomly move the steel casket within the museum space, in any direction they chose.

On several occasions I have insisted that Galindo’s work draws on strategies involving the reenactment of either specific historical facts or contemporary situations. I appreciate her work as an artistic response in which the body itself assumes the role of both the political formulation and the metaphor. Geopolitical relations between the so-called First World and Third World also form part of the backbone of her performances. It is impossible to ignore the artist’s place of origin and the weight of history. Galindo’s actions never stop provoking penetrating observations and reflections about social, political, and cultural settings. From the specific Guatemalan context, Galindo never stops generating criticism of the sinister systematization of networks of corruption, and of drug and human trafficking, that are constructed and consolidated by the state itself in her country. Her public actions generally cause discomfort. They are frequently brutal. Her body, as the subject/object of her actions and only seemingly fragile, always generates analyses of local identity versus the global visions that the art milieu insists upon seeking. Her work, sustained by a field of invisible forces, not only generates interest in the unavoidable history of her country of origin, but also succeeds in invoking heterogeneous discourses and reactions. Through narratives of human existence and its threatened frailty, Galindo’s works insist on denouncing different forms of violence, death, and pain inflicted on bodies beaten by deep-rooted systems of power in Guatemala. However, in an extremely political gesture, the underlying message in America’s Family Prison is the urgent need for a space for empathy, awareness, and eventual understanding of the different complicities, negotiations, and actors at play in the vast landscape of contemporary migrations. And, on a specific level, it seeks to expose, through artistic action, the moral ambiguity of societies of control and surveillance.

Translated from Spanish by Silvina López Medin.

- 1Jean Baudrillard, America, trans. Chris Turner (London: Verso, 1988).

- 2In his seminal essay “Non-Objectualist Theory and Practice in Latin America,” first presented in the context of the First Latin American Conference on Non-Objectualist Art and Urban Art hosted by Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín in May 1981, Juan Acha talked about non-objectualist art practices in Latin America, addressing in particular the processes of signification involved in the development of non-objectualist works of art in the continent. According to Acha, there was a sensitive transfer of social languages delimited by the factors of class and cultural context. The “artistic reality” to which Acha referred emerged from the specificities of social, political, and economical environments of Latin American prospects, providing the non-objectualist work with a particular approach of its aesthetic reflections. See “Non-Objectualist Theory and Practice in Latin America,” post, Museum of Modern Art, https://post.at.moma.org/sources/31/publications/288. For more on the subject, see also Proceedings of the First Latin American Conference on Non-Objectualist Art and Urban Art (Medellín: Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, Museo de Antioquia, 2010).

- 3Marjan Terpstra, “Regina José Galindo: Guatemala Is Violent and so Is My Art,” The Power of Culture (blog), May 2018, http://www.powerofculture.nl/en/current/2008/May/galindo.html.

- 4San Antonio is one of the busiest hubs for undocumented aliens seeking to enter the United States. The San Antonio Border Patrol Station, which opened for operations in September 1988, is responsible for a total geographical area of approximately 18,000 square miles. Because of their numerous industrial centers, support services, and construction companies, Austin, which is the state capital, and San Antonio, attract thousands of undocumented aliens every year. The Union Pacific Railroad runs trains from the south and from the west that pass through the area, and these are frequently used as free transportation by migrants and illegal aliens.

- 5The Chinati Foundation is a contemporary art museum located in Marfa, Texas. Its founder, the artist Donald Judd, began planning it in 1978 with financial support from the Dia Art Foundation. Based on Judd’s ideas of combining art, architecture, and nature, the foundation centered on exhibiting minimalist works by artists such as John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin, and Judd himself. It opened to the public in 1986. Since then, the collection has incorporated works by other artists, including Carl Andre, Ingólfur Arnarsson, Ilya Kabakov, Richard Long, Roni Horn, and Claes Oldenburg, among others.

- 6See Sweeper Metal Fabricators Corp. website, http://www.sweepermetal.com/products/modular-steel-cells/.

- 7Michel Foucault, “The Carceral,” in Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 277.

- 8In 2018, the Trump administration instituted a hard-line immigration policy, under which more than 200 children were separated from their families as they were illegally crossing the border between Mexico and the United States. These separations occurred at the same time as a massive influx of families, most of them coming from the Northern Triangle of Central America. The Trump administration policy failed in its objective to discourage the migrants from traveling and was rescinded nine months later. For a summary of the situation, see Miriam Jordan and Caitlin Dickerson, “US Continues to Separate Migrant Families Despite Rollback of Policy,” New York Times, March, 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/09/us/migrant-family-separations-border.html.

- 9The October Revolution or 1944 Revolution was the civic movement that ended an era of dictatorships and marked a turning point in the history of the country, beginning 10 years of democratic, cultural, and institutional advances that endure today. During this period, the country was governed by a revolutionary junta and two democratically elected presidents: Juan José Arévalo (president from 1945 to 1951) and Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (president from 1951 to 1954). In 1954, in the context of the Cold War, the National Liberation Movement, led by Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas with the support of the US Department of State and the CIA, attacked several villages in Guatemala, by air and land. This armed invasion, popularly known as the counterrevolution, ended the revolutionary period and forced President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán to resign on June 27, 1954.