Julián Sánchez González analyzes the resonances between the Brazilian artist Rubem Valentim and the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi by focusing on two paintings belonging to MoMA’s collection. The essay highlights how these artists deployed hybridized semiotics and different strands of painterly abstraction to critically express their stance towards race, nationhood, and universal human values. Through similar modernist artistic strategies, El-Salahi and Valentim exceeded their local contexts and contested post-colonial and neo-colonial sociopolitical settings in the Global South.

The long decade of the 1960s brought to the fore in Brazil and Sudan groundbreaking artistic practices with paralleling creative devices and political aims. The cases of the artists Rubem Valentim (Brazilian, 1922–1991) and Ibrahim El-Salahi (Sudanese, born 1930) are notorious examples given that, through their work, they delved into purposeful, career-long reformulations of native systems of communication and modernist artistic abstraction with direct stakes in the processes of decolonization, whether cultural or de facto, in their respective countries. For each of them, represented language served as a dual vessel for fertile artistry and engaged social commentary, a view that aimed to build an inclusive national identity while simultaneously exceeding the imagined boundaries of the nation-state. By showcasing an increased awareness of the intersections between aesthetics, politics, and race, Valentim and El-Salahi can be seen as part of a transatlantic semiotic and artistic ethos that supports and expands art historian Kobena Mercer’s claims of the existence of Afro-modern “cosmopolitan contact zones.”1Kobena Mercer, “Cosmopolitan Contact Zones,” in Afro Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic, eds. Tanya Barson and Peter Gorschlüter (Liverpool: Tate Liverpool, 2010), 40. Understood as a model of cross-cultural and artistic translation in the Black Atlantic Diaspora, these resonances reflect a negotiation between the claims for anti-colonial nationalisms and the rise of institutionalized formalism in Western metropolitan art centers.2Ibid.

The recent exhibition Histórias Afro-Atlânticas (Afro-Atlantic Histories), curated by Adriano Pedrosa, Ayrson Heráclito, Hélio Menezes, Lilia Schwarcz, and Tomás Toledo at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), enters into dialogue with Mercer’s thesis on the existence of Afro-modern trends across the Atlantic. Here, the work of different Afro-descendant artists who, from Africa, Europe, and the Americas, were active between 1942 and 1975 is exhibited together following stylistic, conceptual, and biographical criteria.3Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo, “Modernismos Afro-Atlânticos,” in Histórias Afro-Atlânticas, vol. 1, Catalogo, eds. Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo, exh. cat. (São Paulo: MASP, 2018), 314–15. In the section “Modernismos Afro-Atlânticos” (“Afro-Atlantic Modernisms”), the work of Valentim and El-Salahi provides a valuable opportunity to explore what was, by the mid-twentieth century, an unparalleled artistic conversation between Brazil and Sudan. While including articles by notable researchers on African and global modernisms, such as Salah M. Hassan, the two-volume catalogue and anthology that accompanies the exhibition falls short in not providing a detailed analysis of how these artists can be thought of as part of an artistic continuum. This oversight is more pressing considering that Valentim and El-Salahi were displayed side by side in the exhibition Acervo em Transformação: TATE no MASP (Collection in Transformation: TATE in MASP.)4Mounted in Lina Bo Bardi’s characteristic glass easels, this pairing addresses a comparison between Rubem Valentim’s Composição 12 (1962) and Ibrahim El-Salahi’s They Always Appear (1964). A photograph of the images in situ is posted on Adriano Pedrosa’s public Instagram account, which can be accessed here. The MASP has also recently inaugurated the retrospective show Rubem Valentim: Construções Afro-Atlânticas (Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions). This comprehensive exhibition project promises to further illuminate Valentim’s relevance and historiographical importance to national and transnational modern art.

With this in mind, this article presents a more detailed account of the underpinnings of such a comparison by considering Valentim’s untitled painting from 1956–1962 (hereafter Untitled) and El-Salahi’s The Mosque from 1964, both of which are in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).5Rubem Valentim’s Untitled and 2X-2, a painting from the 1960s, entered MoMA’s collection as part of a 2016 gift of more than one hundred works of modern and contemporary Latin American and Caribbean art from the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. This donation also sparked the creation of the Cisneros Institute, an entity at MoMA dedicated to the study of the art from this region. As I will argue, in these works, the artists strived to deconstruct and reassemble, through hybridized motifs and painterly abstraction, the semiotic signs belonging to the visual codes or alphabets commonly present in the cultural systems of their respective places of origin. Following the methodological approaches of art historians Iftikhar Dadi, Salah M. Hassan, and Kobena Mercer, who stress the importance of building non-Western narratives on the formation of global artistic modernisms, this analysis seeks to draw specific points of comparison in the development of the arts of Brazil and Sudan in the second half of the twentieth century.

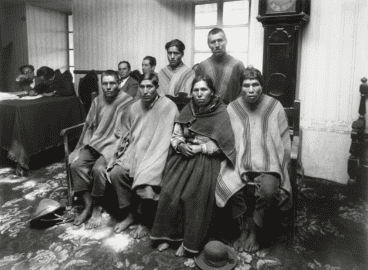

Throughout his career, Valentim, a nonacademic artist from Salvador de Bahia with a professional background in dentistry and journalism, recurrently explored the reimagining of the popular representations of orixás (gods) in Candomblé’s terreiros (sacred ceremonial spaces for worship) in conjunction with letters from the Greco-Roman alphabet. In Untitled, Valentim evidenced the central place these explorations held in his early career. Here, the artist included, for instance, a series of tridents and other trident-like structures that, at first glance, are references to the ferramenta (sacred tool) of Exú, a Candomblé deity known for his role as a messenger between humans and the divine. This same logic applies to the different sizes, colors, and positions of the symbol of the crescent moon, the representation of Iemanjá, the goddess of water and fertility. These figures, however, are often not unique in their compositional structures; they have been reimagined from the more traditional iconographies of Candomblé, and morphed into icons of interstitial and indeterminate qualities. Thus, while it could be useful to pin down the specific associations between these schematic figures and certain deities from within the Candomblé pantheon, the breadth and depth of Valentim’s artistic proposition notoriously exceed the realm of the spiritual and require further inquiry.

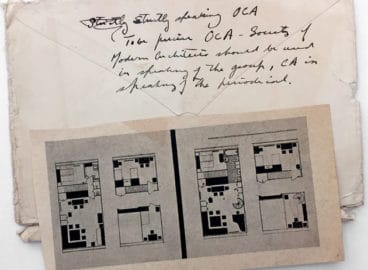

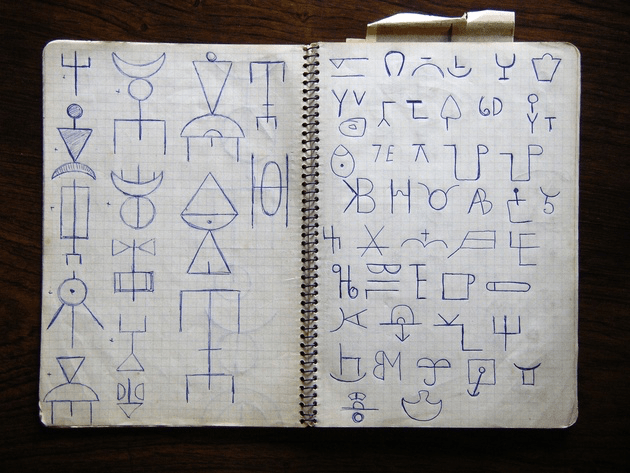

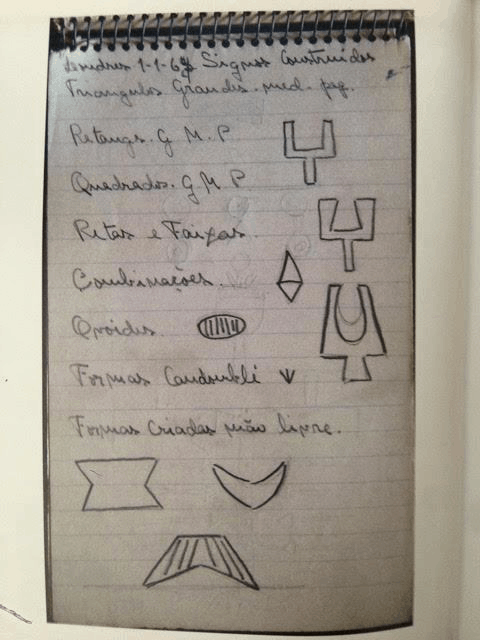

An invaluable clue as to why these visual negotiations are present in Valentim’s art lies in his journals from the early 1960s, which evidence the methodic creative process behind a number of the artist’s early paintings.6I would like to stress the generosity of Laurent Sozzani, a private conservator in Amsterdam, for sharing pictures of Rubem Valentim’s journals, which were instrumental in the development of my argument. Within these pages, he displayed a conscious interest in developing a hybridized subject matter for his artworks, one at the intersection of the sacred and the secular, and within the realm of the linguistic. Valentim’s incursion into semiotic explorations is best seen in a page on which a series of consecutive symbols is laid out in a grid, thus presenting itself as a type of alphabetic system. What seems to resemble the letter E in lines five and six on this page, for example, demonstrates a hybridizing gesture between orixá-based iconography and written romance language. Furthermore, another page of an earlier diary from 1958 makes a reference to these symbols as “Signos Construídos” (“Built Signs”), a labeling effort that reasserts the artist’s interest in a multilayered process for adjudicating importance and meaning in this new visual language. This list notably includes “Formas Candomblé” (“Candomblé Forms”) and “Formas criadas mão livre” (“Forms Created Freehand”). Finally, in terms of the overall composition, the totemic and ceremonial qualities in the layout of these figures also resonate with the gridlike scheme in which written language organizes letters.

It is nonetheless important to note that the agency and creative liberty present in Valentim’s refashioning of Candomblé symbolism is not exclusive to his work. On the contrary, this still seems to be the norm in the everyday life of terreiros, as priests commonly ask artists to create innovative and mixed representations of orixás to use in ceremonial worship.7Daniel Dawson, adjunct professor in the Institute for Research on African American Studies, Columbia University, in conversation with the author, September 12, 2018. The work of the blacksmith and artist José Fernandes, who is also known as Zé Diabo, one of the seminal figures of nonacademic art based on the Candomblé religion, is illustrative of such a stylistic trope.8Ibid. What remains original in Valentim’s canvases within the Brazilian artistic context is, indeed, the hybridization of language, as well as—and this is no less important—their cohesive abstract style, which notably emphasizes a keen and recurrent exploration of geometrical compositions. This interest dialogued with the rise of geometric abstraction in Brazil, particularly in São Paulo from the 1950s onward, a movement Valentim increasingly assimilated and reformulated in his work after relocating to this city in 1957.9Kimberly L. Cleveland, “Candomblé as Artistic Inspiration: Syncretic Approaches,” in Axé Bahia: The Power of Art in an Afro-Brazilian Metropolis, eds. Patrick A. Polk et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2018), 219. This shift is best seen in the large geometric color surfaces that dominate the background composition of Untitled, while specific smaller figures, such as triangles, circles, and semicircles, establish an interaction through line work and color.

Due to its overt spiritual connotations and direct relationship with Candomblé, Valentim’s work, as opposed to that of his contemporaries, such as Hélio Oiticica or Lygia Clark, has been posited by prominent intellectuals as an “anthropological” take on Brazilian geometric abstract art.10Gabriela Rangel Mantilla, “Rubem Valentim,” in Geometric Abstraction: Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 2001), 258. This raises poignant questions about the historically fraught relationship between ethnographic perspectives and the art of the African diaspora. Because of Valentim’s widespread use of abstraction as a stylistic vessel, or as art historian Edward J. Sullivan argues, a “system of expression,” to speak about the secondary role of Afro-Brazilian culture in the visual arts, such a claim could be partially sustained.11Edward J. Sullivan et al., Brazil: Body & Soul, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2001), 361. However, these interpretative models do not necessarily account for the complexity of Valentim’s semiotic interests, which were not only focused on the creation of a distinct type of Brazilian visual language. In fact, they openly strived to invite the artistic circles of São Paulo to a deeper understanding of Afro-Brazilian culture.12For Emanoel Araújo, this is perhaps best seen in Valentim’s interest in the creation of a distinct style of Brazilian art that he dubbed “Riscadura Brasileira” (“Brazilian Graphics”), which would be anchored in ritual ideograms, Afro-Brazilian roots, and an internationally intelligible syntax. See Emanoel Araújo, “Exhibiting Afro-Brazilian Art,” in ibid., 323. By extension, his work also sought a more participatory position for Afro-descendant individuals in a country where prevalent and unsustained discourses around “racial democratic” equality exist—albeit the notion of “racial democracy,” or the idea that there are harmonious race relationships within the country, has long been in question.13Alexandre Emboaba Da Costa, “Confounding Anti-Racism: Mixture, Racial Democracy, and Post-Racial Politics in Brazil,” Critical Sociology42, no. 4–5 (July 2016): 496. This historical context also resonates with Paul Gilroy’s notion of “postcolonial melancholia,” which he defines, thinking specifically about the aftermath of the disintegration of the British Empire, as a persisting and recurrent dynamic of racial segregation embedded in policy making and everyday life in the United Kingdom. In the particular case of Brazil, it seems that the remnants of the historical and cultural impetus of imperial exclusion from its colonial past take root in the form of a neocolonial strategy for domination of disenfranchised societal groups as the notion of “racial democracy” arises in the twentieth century. See Paul Gilroy, Postcolonial Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 98–106.

Originating in Salvador da Bahia, Valentim’s work would signal his awareness of a historical context within the fraught inner workings of a Republican political system, but also of himself as a diasporic subject with dual roots across the Atlantic. A page from his personal diaries from 1960–61, for example, attests to his interest in African politics, for one page features the word “Lumumba” over a series of concentric, fine-lined circles. The line work in this sketch differs noticeably from that of other drawings in Valentim’s diaries, which are noteworthy for their structured and methodic compositional elements including, for example, specific color-coding instructions. With this in mind, it is possible to posit that this piece hints at a meditative attitude, and perhaps also a rupture in Valentim’s creative synergy. At any rate, for its content and temporal correspondence to the making of the diary, the inspiration for this drawing can be safely attributed to the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, an independence leader and also prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 1961. It is likely that Valentim had access to news of this kind given that, at the time, several newspapers—including Notícias de Ébano (1957), O Mutirão (1958), and Níger (1960)—collectively known as the “imprensa negra” (black press) were being published in São Paulo.14Petrônio Domingues, “Negro no Brasil: Histórias das lutas antirracistas [“Black in Brazil: History of the Fights against Racism],” in Histórias Afro-Atlânticas, vol. 2, Antologia, eds. Amanda Carneiro and Adriano Pedrosa (São Paulo: MASP, 2018), 460–61. Even after the military coup of 1964 and the ensuing persecution of race activists, these publications would, by the end of the 1970s, pave the way for the reorganization of social movements against racism.15Ibid. This was particularly notorious in the work of the Movimento Negro Unificado (MNU), an organization that found inspiration in the American Civil Rights Movement and the struggles for independence in African Portuguese-speaking countries such as Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and Angola.16Ibid. Valentim’s sketch, then, captures, and to a certain extent, prefigures the growth of this transnational political effervescence in Brazil. It is precisely this exchange of information and political awareness that has motivated art historians and curators, including Mercer and Pedrosa, to recover the missing links to the arts of the Black Atlantic diaspora. By bringing to light these connections across the Atlantic, their projects help in reevaluating previously accepted art historiographical narratives of an exclusionary nature.

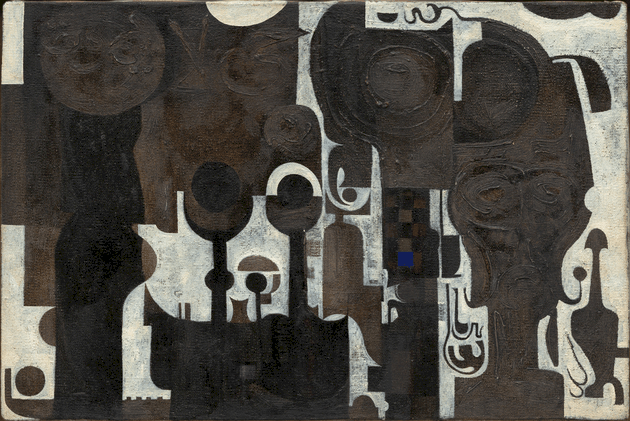

Another fine example of the growing transnational consciousness around questions of race and inclusivity can be seen in the work of the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi. Born in Khartoum and formally trained in painting at the Slade School of Fine Art in London between 1954 and 1957, El-Salahi achieved a unique style by deconstructing Arabic letters and calligraphy. This would not be the final destination of El Salahi’s artistic explorations in his early career, however, for the subject matter of his work at this time also incorporates crescents, arabesques, and certain African motifs, such as masklike objects.17Salah M. Hassan, “Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, eds. Salah M. Hassan and Sarah Adams, exh. cat. (New York: Museum for African Art, 2012), 18. See also Dadi, “Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism,” 555. In his 1964 painting The Mosque, the conflation of these elements is perceptible in the interplay of sinuous lines and vertical figures painted in either black or dark brown throughout the canvas. The African-influenced elements are seen in the foregrounding of a human face on the right side. This figure is depicted in a schematic manner through the use of textured pigments. While in the calligraphic elements to the left, a focus on the negative spaces between figures reveals freehand gestures carefully placed against a light-blue-and-white background. The fusion of Arabic and African cultural elements present in this iconographic mixture makes it difficult to distinguish where one ends and the other begins, thus suggesting a deconstruction of original symbolic and religious connotations, even though the subject of the painting remains, indeed, a mosque.

El-Salahi’s culturally hybridized style follows the steps of a previous generation of artists whose explorations sought the exaltation of the intricate design and poetic possibilities of Arabic language. This is the case of the Hurufiyya (also spelled Huroufiyah) movement of artists from the 1940s and 1950s, whose presence in Northern Africa and the Middle East was notable, as the case of the Iraqi-Syrian artist Madiha Umar (1908–2005) illustrates. For Umar, calligraphy’s sensuous pleasures laid on the mystical nature of what she called the “subtle balance of the mathematical and the free abstract element,” which also led her to use “the Arabic alphabet as a basis for abstract painting, gradually developing it from plain surface manipulation into the more expressive dynamic movement of a thought in a picture.”18Madiha Umar, “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949–1950),” in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, eds. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 141–42. Art historian Salah M. Hassan has identified other precursory figures at work on similar semiotic strategies in Sudan, including the painter Osman Waqialla (1925–2007), whose work eventually led to the creation of the Khartoum school, an art movement with which El-Salahi was associated from its inception.19Hassan, “Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism,” 15–17. The work this loose collective of artists envisioned was a typically hybrid Sudanese visual identity, one that, at least in the case of El-Salahi, would unite seemingly disparate Arabic and African cultural traits present across Sudanese territory with the aim of better understanding the region’s local culture and heritage.20Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose, Tate Modern, July 5, 2013. Hassan Musa, a Sudanese artist who studied under El-Salahi at Gordon Memorial College, home of the Khartoum school, has notably expressed his discontent with the confinement of African shared cultural traits to a number of homogenizing motifs. This resistance toward cultural reductionism characterized the views of the generation of artists that succeeded El-Salahi’s and who self-identified as the Crystalist Group. For more on this tension, which has been posited as productive and beneficial for Sudanese art by both parties, see Hassan Musa, “The Wise Enemy: Between Artist of the Authority and the Authority of the Artist,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi, 69–79; Hassan Abdallah et al., “The Crystalist Manifesto (1976),” in Modern Art in the Arab World, 393–401; and Anneka Lenssen, “‘We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context,” The Museum of Modern Art, post, April 4, 2018 [last viewed October 12, 2018].

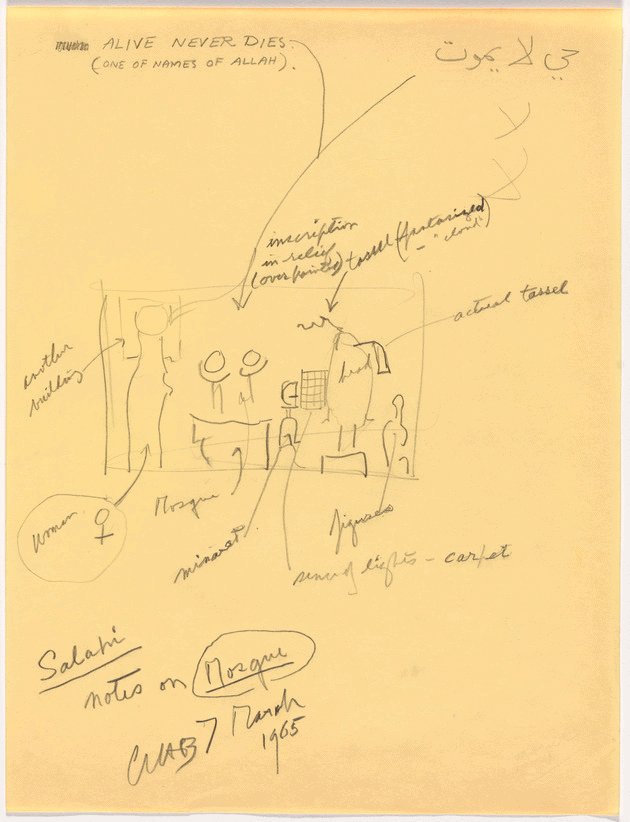

El-Salahi’s composite iconographies, such as those present in The Mosque, attempted, as the artist has asserted, “to create a new visual alphabet incorporating a contemporary artistic concept” exploring “the symbolic potential” of visual hybridization.21Ibrahim El-Salahi, “The Artist in His Own Words,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi, 88. However, this did not necessarily imply an interest in the total secularization of this painting, as stated previously, since the composite artistic gestures present in The Mosque, although notable for describing El-Salahi’s work, should not be confused with the overall intention of the piece, which remains primarily devotional. A 1965 annotated sketch of The Mosque, in fact, reveals that the composition also includes clearly defined religious calligraphic inscriptions, which are not recognizable at first glance given that they blend with the other motifs in a subtle interplay of line, color, and texture. In effect, the upper section of the drawing outlines the Arabic characters for “Alive Never Dies (One of the Names of Allah)” and describes them as included in relief in the actual painting, a fact that is corroborated upon a closer look at the work. With this in mind, the recent assessment by Amir Nour (born 1939), artist and professor of fine arts and former member of the Khartoum school, of El-Salahi’s work as “reflecting an influence of traditional African carvings rather than Arabic art of calligraphy” seems unsustained.22Amir Nour, “Three Years of Teaching Art in Khartoum, 1962–65,” in Modern Art in the Arab World, 141–42.

Further, notable descriptive elements in this drawing reassert the presence of other traditional African motifs, such as two decorative tassels, one “actual” and the other “fantasized,” emanating from the masklike figure on the right side of the canvas, as well as the sinuous silhouette of a “woman” on the right, and that of an indeterminate “figure” on the far right. In their anonymity, elongation, and schematic plasticity, they could possibly be referencing nineteenth- and twentieth-century sculptural wooden carvings from either the Bari or Bongo peoples of Sudan. The artist’s attention to the details on the architectural elements is also worthy of mention as it not only corroborates that the form at center stage is a highly abstracted mosque, but also points to the depiction of a “minaret” and a “screen of lights,” in reference to the structure’s architectural elements, or of a “carpet,” as the colorful gridlike formation suggests. In spite of El-Salahi’s notated description, all of these elements are the result of an imaginative process in which he combined the real and fictional, describing them as “glimpses of alien worlds as a child and as an adult.” Furthermore, for this specific piece, El-Salahi stated:

“No particular model or scene had been used for this painting. Just a group of faraway recollections. They seem to dominate my thinking when I feel the urge to paint. I have found out through living with myself all these years that I am possessed by something I don’t know what.” He goes on to say, “[T]his work is one of a group that has come through following a series of dreams I have had after the death of my father in mid October 64 [sic].”23Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

By tapping into the supernatural and the unconscious, El-Salahi has been consistent throughout his career, and The Mosque is no exception, in exploring the limits of what he calls “human rational cognition” by “leaving behind the rational pulse of the conscious mind” and placing emphasis on the “invisible and metaphysical.”24Ibrahim El-Salahi for The Museum of Modern Art Collections Records, November 2, 1965.

Through these visual dialogues, El-Salahi, as well as founders and members of the Khartoum school, reacted to the aftermath of Sudan’s independence from British and Egyptian colonial rule in 1956. According to art historian Salah M. Hassan, El-Salahi was able to create an artistic corpus that resonates with the work of other African modern artists, such as the Armenian-Ethiopian Alexander “Skunder” Boghossian (1837–2003) and the South African Ernest Mancoba (1904–2002).25Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Through their shared artistic style featuring, among other elements, earthy tones and abstract textural work, these individuals simultaneously sought to build, in imaginative aesthetics, a national identity after the rupture brought by the postcolonial movements of the 1950s and 1960s in the African continent.26Hassan, “Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism,” 11. Similarly, art historian Iftikhar Dadi argues that thinking about El-Salahi within a nationally based geographical model is limiting in terms of interpreting his work, which resonated not only with artists affiliated with the Hurufiyya movement, but also with other artists from the Arab world, for instance in Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan, who were also invested in creating a modern language through calligraphy.27Ibid. Their work, much like El-Salahi’s, sought to recover a type of visual expressivity that had been repressed under colonialism while conversing with larger trends of metropolitan and cosmopolitan modernisms.28Iftikhar Dadi, “Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective,” South Atlantic Quarterly 109, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 559. These artists notably included Sadequain Naqqash in Pakistan, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi in Iran, and Shakir Hassan Al Said in Iraq. In this sense, Dadi argues, El Salahi’s work, though nationally based, also strived to explore universal values exceeding his particular context and, as such, he could be thought of as a West African and Arab artist as much as a Sudanese one.29Ibid., 560. It is precisely the mixture and indeterminacy of the connection between linguistics and imagery, together with the engagement with a Pan-African and Pan-Islamic artistic conversation, that El-Salahi deems as the core feature, and also legacy, of his lifelong career as a visual artist.30Ibid., 566.

As I have discussed thus far, it is possible to discover continuity in Rubem Valentim’s and Ibrahim El-Salahi’s work across a transatlantic axis given that their shared interest in building more comprehensive and cohesive national identities was pursued through strikingly similar creative processes featuring hybridized semiotics and painterly abstraction. To this end, it is pivotal to highlight two instances in which the artists geographically coincided in the period when the works Untitled and The Mosque were made. In 1962, UNESCO awarded El-Salahi a scholarship that allowed him to travel to South America, in particular to Peru, Mexico (where he met the artist Rufino Tamayo [1899–1991]), and Brazil.31Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Although the specifics of this trip remain unclear, his passing through Brazil involved some time in Rio de Janeiro and one day in Brasilia.32Nour, “Three Years of Teaching Art in Khartoum,” 211; Ibrahim El-Salahi for the Museum of Modern Art Collections Records, November 2, 1965; and Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Also, it is worth mentioning the fact that, in 1964, two years after his UNESCO sojourn, El-Salahi traveled for a year in the United States as a Rockefeller fellow in art. During this time, the artist met with seminal figures such as Romare Bearden from Spiral, a group of African American artists active during the first half of the 1960s, and Alfred Barr, Jr., at the time director of MoMA, and he was supposed to meet with Malcolm X, who was assassinated one week before El-Salahi’s arrival. See Ibrahim El-Salahi interviewed by Sarah Dwider, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, December 13, 2016; Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. El-Salahi was interested in visiting Salvador da Bahia, commonly known as the Mecca for black culture in the Americas, although time constrictions prevented this.33Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Nonetheless, the year 1962 remains crucial since the artists coincided in Rio de Janeiro: Valentim’s travels to Europe would not start until he was granted a foreign travel prize for his participation in the XI National Salon of Fine Arts in 1963.34Ibid.; and Cleveland, “Candomblé as Artistic Inspiration,” 208. Four years later, in April 1966, after both Untitled and The Mosque had been finished, Valentim and El-Salahi coincided yet again, this time as representatives of their countries to the First World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal.35Mantilla, “Rubem Valentim,” 258; Kimberly L. Cleveland, Black Art in Brazil: Expressions of Identity (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013), 33. This major event took place after Senegal’s independence from France under the mandate of Léopold Sédar Senghor, a key proponent of the Négritude movement. Both organizers and attendees sought to further transnational collaborative efforts for integration between African and African-diasporic nations.36Mantilla, “Rubem Valentim,” 258; Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. This was a particularly interesting time for such connections to take place. On the one hand, Brazil, at the time under a military dictatorship that lasted from 1964 to 1985, had shown little interest in Afro-Brazilian culture until African independence movements consolidated.37Anthony J. Ratcliff, “When Négritude Was in Vogue: Critical Reflections of the First World Festival of Negro Arts and Culture in 1966,” Journal of Pan African Studies 6, no. 7 (February 2014): 168. Sudan, on the other hand, torn by a protracted civil war between its Northern and Southern Arab and African constituents (1955–1972), had just transitioned to a multiparty democratic system that would last only briefly—from 1964 to 1969, when Colonel Gaafar Mohamed el-Nimeiri seized power.38Kimberly L. Cleveland, “Afro-Brazilian Art as a Prism: A Socio-Political History of Brazil’s Artistic, Diplomatic and Economic Confluences in the Twentieth Century,” Luso-Brazilian Review 49, no. 2 (2012): 103. Though it remains to be elucidated whether Valentim and El-Salahi personally met, their itinerancies, together with their works and creative processes, point at a decided social consciousness of their subjectivity as black artists—albeit of notably different kinds—at the interstices of a politically strained cultural milieu.

Under this light, the resonances between Valentim’s and El-Salahi’s artistic proposals constitute clear indications of a transatlantic and interrelated growing awareness of hybridized black identities in both Africa and Latin America. As a result, this comparative analysis converses and deepens art historian Kobena Mercer’s claims on the existence of “cosmopolitan contact zones” between the United States and the Caribbean during the 1940s. For Mercer, these interactions created a distinct type of Afro-modernism that acknowledged and controverted its historically subordinated and diasporic condition.39Anneka Lenssen, “‘We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context,” The Museum of Modern Art, post, April 4, 2018 [last viewed October 12, 2018]. Very much in line with Iftikhar Dadi’s writing, Mercer claims that the nationalist perspective ascribed to black artists working in this period is limiting and, therefore, requires broader frameworks of analysis.40Mercer, “Cosmopolitan Contact Zones,” 40. The conflictive tensions between these artists’ negotiations with anti-colonial nationalism and the prevalence of a formalist narrative in modern art point at the possibility of establishing these models of cosmopolitan cross-cultural translation.41Ibid. Thus, the south-to-south resonances between Valentim and El-Salahi speak of simultaneous searches for similar avenues of creation responding to the presence of pervasive and systematic racial exclusions from colonial and neocolonial contexts of domination. By re-signifying, under the tenets of painterly abstraction, the imagery of the Afro-Brazilian religion of Candomblé and the Greco-Roman alphabet in the case of Valentim, and African visual motifs with Arabic calligraphy in the case of El-Salahi, both artists aimed to build powerful tools of cultural and political resistance.42Ibid., 41. Through their art, both reasserted their positions as national and transatlantic individuals mindful of the historical processes leading to the sociopolitical turbulences of their regions while simultaneously reclaiming a space for creative agency.43El-Salahi’s political beliefs root for the self-determination and unity of Sudan, and his artistic work reflects broader historical tendencies of an anti-colonial nature catering to the political needs of an increasing pushback for self-determination of the Arab, African, and transatlantic worlds. However, it should be noted that the artist also worked for the Sudanese government in various capacities. Most remarkable was his appointment as assistant cultural attaché to the Sudanese embassy in London from 1969 to 1972, and his position as minister of culture, a post he held until 1975. After this, El-Salahi was imprisoned for six months by al-Nimieri’s regime, a traumatic event leading the artist to a self-imposed exile from Sudan after his liberation.

- 1Kobena Mercer, “Cosmopolitan Contact Zones,” in Afro Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic, eds. Tanya Barson and Peter Gorschlüter (Liverpool: Tate Liverpool, 2010), 40.

- 2Ibid.

- 3Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo, “Modernismos Afro-Atlânticos,” in Histórias Afro-Atlânticas, vol. 1, Catalogo, eds. Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo, exh. cat. (São Paulo: MASP, 2018), 314–15.

- 4Mounted in Lina Bo Bardi’s characteristic glass easels, this pairing addresses a comparison between Rubem Valentim’s Composição 12 (1962) and Ibrahim El-Salahi’s They Always Appear (1964). A photograph of the images in situ is posted on Adriano Pedrosa’s public Instagram account, which can be accessed here. The MASP has also recently inaugurated the retrospective show Rubem Valentim: Construções Afro-Atlânticas (Rubem Valentim: Afro-Atlantic Constructions). This comprehensive exhibition project promises to further illuminate Valentim’s relevance and historiographical importance to national and transnational modern art.

- 5Rubem Valentim’s Untitled and 2X-2, a painting from the 1960s, entered MoMA’s collection as part of a 2016 gift of more than one hundred works of modern and contemporary Latin American and Caribbean art from the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros. This donation also sparked the creation of the Cisneros Institute, an entity at MoMA dedicated to the study of the art from this region.

- 6I would like to stress the generosity of Laurent Sozzani, a private conservator in Amsterdam, for sharing pictures of Rubem Valentim’s journals, which were instrumental in the development of my argument.

- 7Daniel Dawson, adjunct professor in the Institute for Research on African American Studies, Columbia University, in conversation with the author, September 12, 2018.

- 8Ibid.

- 9Kimberly L. Cleveland, “Candomblé as Artistic Inspiration: Syncretic Approaches,” in Axé Bahia: The Power of Art in an Afro-Brazilian Metropolis, eds. Patrick A. Polk et al., exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2018), 219.

- 10Gabriela Rangel Mantilla, “Rubem Valentim,” in Geometric Abstraction: Latin American Art from the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Collection, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 2001), 258.

- 11Edward J. Sullivan et al., Brazil: Body & Soul, exh. cat. (New York: Guggenheim Museum, 2001), 361.

- 12For Emanoel Araújo, this is perhaps best seen in Valentim’s interest in the creation of a distinct style of Brazilian art that he dubbed “Riscadura Brasileira” (“Brazilian Graphics”), which would be anchored in ritual ideograms, Afro-Brazilian roots, and an internationally intelligible syntax. See Emanoel Araújo, “Exhibiting Afro-Brazilian Art,” in ibid., 323.

- 13Alexandre Emboaba Da Costa, “Confounding Anti-Racism: Mixture, Racial Democracy, and Post-Racial Politics in Brazil,” Critical Sociology42, no. 4–5 (July 2016): 496. This historical context also resonates with Paul Gilroy’s notion of “postcolonial melancholia,” which he defines, thinking specifically about the aftermath of the disintegration of the British Empire, as a persisting and recurrent dynamic of racial segregation embedded in policy making and everyday life in the United Kingdom. In the particular case of Brazil, it seems that the remnants of the historical and cultural impetus of imperial exclusion from its colonial past take root in the form of a neocolonial strategy for domination of disenfranchised societal groups as the notion of “racial democracy” arises in the twentieth century. See Paul Gilroy, Postcolonial Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 98–106.

- 14Petrônio Domingues, “Negro no Brasil: Histórias das lutas antirracistas [“Black in Brazil: History of the Fights against Racism],” in Histórias Afro-Atlânticas, vol. 2, Antologia, eds. Amanda Carneiro and Adriano Pedrosa (São Paulo: MASP, 2018), 460–61.

- 15Ibid.

- 16Ibid.

- 17Salah M. Hassan, “Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi: A Visionary Modernist, eds. Salah M. Hassan and Sarah Adams, exh. cat. (New York: Museum for African Art, 2012), 18. See also Dadi, “Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism,” 555.

- 18Madiha Umar, “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art (1949–1950),” in Modern Art in the Arab World: Primary Documents, eds. Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018), 141–42.

- 19Hassan, “Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism,” 15–17.

- 20Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose, Tate Modern, July 5, 2013. Hassan Musa, a Sudanese artist who studied under El-Salahi at Gordon Memorial College, home of the Khartoum school, has notably expressed his discontent with the confinement of African shared cultural traits to a number of homogenizing motifs. This resistance toward cultural reductionism characterized the views of the generation of artists that succeeded El-Salahi’s and who self-identified as the Crystalist Group. For more on this tension, which has been posited as productive and beneficial for Sudanese art by both parties, see Hassan Musa, “The Wise Enemy: Between Artist of the Authority and the Authority of the Artist,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi, 69–79; Hassan Abdallah et al., “The Crystalist Manifesto (1976),” in Modern Art in the Arab World, 393–401; and Anneka Lenssen, “‘We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context,” The Museum of Modern Art, post, April 4, 2018 [last viewed October 12, 2018].

- 21Ibrahim El-Salahi, “The Artist in His Own Words,” in Ibrahim El-Salahi, 88.

- 22Amir Nour, “Three Years of Teaching Art in Khartoum, 1962–65,” in Modern Art in the Arab World, 141–42.

- 23Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

- 24Ibrahim El-Salahi for The Museum of Modern Art Collections Records, November 2, 1965.

- 25Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

- 26Hassan, “Ibrahim El-Salahi and the Making of African and Transnational Modernism,” 11.

- 27Ibid.

- 28Iftikhar Dadi, “Ibrahim El Salahi and Calligraphic Modernism in a Comparative Perspective,” South Atlantic Quarterly 109, no. 3 (Summer 2010): 559. These artists notably included Sadequain Naqqash in Pakistan, Charles Hossein Zenderoudi in Iran, and Shakir Hassan Al Said in Iraq.

- 29Ibid., 560.

- 30Ibid., 566.

- 31Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

- 32Nour, “Three Years of Teaching Art in Khartoum,” 211; Ibrahim El-Salahi for the Museum of Modern Art Collections Records, November 2, 1965; and Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Also, it is worth mentioning the fact that, in 1964, two years after his UNESCO sojourn, El-Salahi traveled for a year in the United States as a Rockefeller fellow in art. During this time, the artist met with seminal figures such as Romare Bearden from Spiral, a group of African American artists active during the first half of the 1960s, and Alfred Barr, Jr., at the time director of MoMA, and he was supposed to meet with Malcolm X, who was assassinated one week before El-Salahi’s arrival. See Ibrahim El-Salahi interviewed by Sarah Dwider, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, December 13, 2016; Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

- 33Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

- 34Ibid.; and Cleveland, “Candomblé as Artistic Inspiration,” 208.

- 35Mantilla, “Rubem Valentim,” 258; Kimberly L. Cleveland, Black Art in Brazil: Expressions of Identity (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2013), 33.

- 36Mantilla, “Rubem Valentim,” 258; Ibrahim El-Salahi, interviewed by Salah M. Hassan and Elvira Dyangani Ose.

- 37Anthony J. Ratcliff, “When Négritude Was in Vogue: Critical Reflections of the First World Festival of Negro Arts and Culture in 1966,” Journal of Pan African Studies 6, no. 7 (February 2014): 168.

- 38Kimberly L. Cleveland, “Afro-Brazilian Art as a Prism: A Socio-Political History of Brazil’s Artistic, Diplomatic and Economic Confluences in the Twentieth Century,” Luso-Brazilian Review 49, no. 2 (2012): 103.

- 39Anneka Lenssen, “‘We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context,” The Museum of Modern Art, post, April 4, 2018 [last viewed October 12, 2018].

- 40Mercer, “Cosmopolitan Contact Zones,” 40.

- 41Ibid.

- 42Ibid., 41.

- 43El-Salahi’s political beliefs root for the self-determination and unity of Sudan, and his artistic work reflects broader historical tendencies of an anti-colonial nature catering to the political needs of an increasing pushback for self-determination of the Arab, African, and transatlantic worlds. However, it should be noted that the artist also worked for the Sudanese government in various capacities. Most remarkable was his appointment as assistant cultural attaché to the Sudanese embassy in London from 1969 to 1972, and his position as minister of culture, a post he held until 1975. After this, El-Salahi was imprisoned for six months by al-Nimieri’s regime, a traumatic event leading the artist to a self-imposed exile from Sudan after his liberation.