These two texts, one by a well-known artist, the other by an eminent critic—both Tokyoites—, first appeared in Japanese in 1963 and 1968, respectively. Each provides a colorful account of interactions between artists from Tokyo and New York in the ’60s, and both present Japanese reflections on American art at that time. Here the texts accompany essays newly commissioned by

post from Hiroko Ikegami and Abigail Sebaly.

Source contents

The Way to Avant-Garde (excerpt)

By Shinohara Ushio 1968

Publication: The Way to Avant-Garde

Publisher: The Art Publishing

Language: Japanese

Translated by Marie Iida

Appearing in a Public Interview

Robert Rauschenberg, the greatest of all the greats, the most important young master of the postwar avant-garde art world, who earned America its first Grand Prize in a dramatic upset at the 1964 Venice Biennale, arrived in Japan as the art director [sic] of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company near the end of that same year. On this occasion, “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg” took place.1Rauschenberg was the stage designer, not the art director, of the company.

In front of more than five hundred prospective members of the ravenous, growing Japanese art community, who had gathered in Sogetsu Art Center in Akasaka, Tokyo, Rauschenberg guzzled whiskey oranges and, together with his three assistants, pulled out from somewhere a gold folding screen—a tableau of traditional Japanese painting that even natives such as us had rarely seen—and, sweating profusely, attacked it with a drill.

This was the second public interview hosted by the critic Yoshiaki Tōno, who had caused a sensation among young people at the public interview “Anti-Art, Yes or No?” in January 1964.

Rauschenberg is known for his use of primary color prints, and beginning with Monogram, in which he wrapped a car tire around the chest of a goat dabbed with thick paint, most of his works have been introduced to Japan. For us, each such occasion has served as a driving force that suffuses our impoverished art community with a new spirit. Especially his bold use of found objects, such as a fan, a broken traffic light, or a stuffed bird—like tableaux made out of props from a Happening—gave us a shock that made it seem impossible ever to imagine a work more modern.

With a global artist such as this responding to our questions, one would be a fool not to be thrilled. The crowd, which had gathered in the small, sweltering Sogetsu Art Center with a pile of questions, looked with anticipation at the dimly lit stage. However, our rising expectations were soon shattered. Onstage, the event started at once, and our painstakingly formed and selected questions were sent through a telephone inside the venue to the side of the stage where Mr. Tōno sat. Before they reached Rauschenberg, the questions were processed through composer Toshi Ichiyanagi’s so-called “breaking machine,” which shredded the questions so that in the end they reverberated through the floor as electronic noise.2The machine is described as an electronic sound distorter in Hiroko Ikegami’s essay “Lost in Translation? ‘Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg.’ “ This dismayed even Mr. A of the art journal Bijutsu Techō (Art notebook), who had arrived eagerly with two female stenographers and a tape recorder in hand.3Mr. A was an editor of the art journal Bijutsu Techō (Art notebook).

However, I exchanged sly smiles with the papier-mâché artist Nobuaki Kojima. We had known this would happen. The two of us, who had arranged in advance with Mr. Tōno to make a powerful impression on Mr. Rauschenberg with our works, sat impatiently with the interpreter Mr. Shūji Takashina at a table to the left of the stage and waited for Mr. Tōno’s sign—right hand raised twice—as he read aloud from the question sheet.

In fact, the day before the event, I had received a visit from Rauschenberg and company.

Getting an OK for Imitation

The clattering sound of the company’s footsteps down the hallway as they approached my apartment made my heart pound. After all, Rauschenberg was now a popular artist at the height of his career in the global art world, and we were only seven years apart in age. The only difference between us was the price of our paintings: an average of $20,000 (about 8 million yen) per work for Bob, and 20,000 yen for me. But I wasn’t going to be at his mercy. My works for the group exhibition Left Hook (featuring Shintaro Tanaka, Nobuaki Kojima, Tatsumi Yoshino, Kazutada Tsubouchi, and myself), which would take place in December that year at Shinjuku’s Tsubaki Kindai Gallery, were emerging one by one in the courtyard outside my veranda. The masterpiece among them, the papier-mâché statue Marcel Duchamp in Thought, measured over two meters high even in a seated pose. As I gazed at it I smiled in spite of myself; I wondered how the visitors would react when they saw it.

“Come in, please.”

I ushered them into the dining room with their shoes on, and the drinking and eating started immediately. With cups of whiskey in hand, everyone did as they pleased. Some focused on the food, some on the drinks, and, from time to time, they stared intently at my mother making dolls in the adjacent Japanese-style room. Gilt-edged sunglasses and a khaki jacket. A coll Yankee, Bob did not seem like a great master at all. The Ivy rebels in Ginza would immediately want to imitate his style; he had a perfect sense of TPO (Time, Place, Occasion). He kept hold of his whiskey as I led him out into the courtyard to show him my works. (In my heart, I was worried that he would look at my Imitation art and attack me in a rage). He stared silently at the statue of Marcel Duchamp in Thought with its spinning head.4The sculpture’s rotating head is driven by a motor. The Swedish museum curators who had visited the day before had made a big fuss over the statue when they saw it, saying I should set fireworks inside its head, but Bob’s reaction was the exact opposite.

I showed one work after another to Bob, who remained silent. The Beatles, Lovely Lovely America, Don Shorander with Four Gold Medals, Air Mail—it was as if I were reproducing American Pop. But Rauschenberg impressed me as expected. He never said anything cowardly, like that he wanted to see something more unique to Japan. To him, the Zen country of Japan did not matter. The only thing that mattered was the confrontation between works of art. That’s why however closely I imitate Pop art—or embody Pop itself—it stirred in him the same feeling of tension and rivalry as would any work of emerging new art in America.

“May I imitate your works?”

There it was. My special question. I thought about showing him my Coca-Cola Plan5The work was created in 1964 and is now in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama. as well, but didn’t have the courage to do so. I’d bring it out during tomorrow’s public interview anyway.

“Sure.”

I was disappointed by his immediate OK. I was expecting him to hit me, or at least pause for a little bit. Well, since I got the OK in person, I will imitate his works more and more. But the outcome was the opposite: for after my meeting with Bob, I lost interest in Imitation art.

Rauschenberg Refuses to Answer Questions

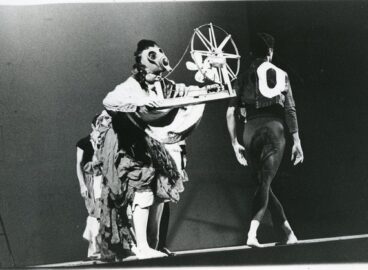

Mr. Tōno raised his right hand twice. We were up! Kojima and I ran onstage. I dragged the statue of Duchamp out from its hiding place to the center of the stage while Kojima did the same with his flag-draped figure, which held a large placard with the word “QUESTION” on it.

Question 1: The enlarged face of Marilyn Monroe, in the same way as the Mona Lisa with the beard, follows the same Dada spirit that has existed since 1916. This methodology of Dadaism within the plastic arts has an established value and authority, and it is also as archaic as the Legion of Honor or a moustache. What does Mr. Rauschenberg, the Neo-Dadaist, make of this?

Question 2: What would you do if an Imitation art version of your work, exactly the same as the original but enlarged ten to fifty times and equipped with a powerful effect, appeared right next to it?

Question 3: Your work has an extremely intuitive effect, that is to say, like the tableaux of Picasso, it impresses us with the artist’s natural talent and brushwork. However, a superior sensibility does not always express a superior idea. Rather, when expressing an important idea, wouldn’t an extraordinary sensibility or pathological nature be a distraction? In your tableaux featuring discarded objects (a traffic light, a stuffed bird, a chair, a bed) dripped with primary colors, I cannot help but detect a method that relies too heavily on a Picasso-like sensibility. What do you make of this?

I read my questions aloud in both English and Japanese. (Mr. Takashina had translated them.) Bob, wearing a gas station attendant’s uniform, continued to work in silence and did not respond no matter what I said. When I placed my question sheet at his feet, he pasted even that on the screen.

All right, we’ll move on then. I turned on the switch of Marcel Duchamp in Thought. It began to move creakily, and as it picked up speed, its head spun into a white blur. Amazing. The eyes of the crowd focused on it at once. Bob, with a brush in his hand, gave it a sidelong glare.

We had reached a limit. Duchamp’s head was about to blow away, and so I had to turn the switch off. Nothing happened. Bob continued to work. He went on like that for four and a half hours. The curtain was drawn. Bob, terribly drunk, looked at me and pretended to take me down with a karate move. And until the end, he carried my Coca-Cola Plan in his arms and refused to let go, calling it “my son.”

Rauschenberg’s Combine Statement

By Tono Yoshiaki December 1, 1963

Publication: SAC Journal

Language: Japanese and English

Translated by Marie Iida

Dear Tono,

I’ve enclosed my manuscript. I hope it reaches you in time. Right now, along with Merce [Cunningham], John [Cage], David [Tudor], and the dancers, I am riding on a Volkswagen bus. Everyone says hello. We are touring through the land of cowboys and Indians. I’m sure no one will be able to translate this manuscript. Please, do not revise or change it in any way. Send me a letter.

Bob

It was about mid-November when I received this letter, postmarked Austin, Texas, from Rauschenberg. The manuscript he refers to is something I had requested for the feature “Gendai sakka no hatsugen” (Statements by Contemporary Artists) planned for the seven hundredth issue (June 1963) of the monthly art magazine Mizue (Water Painting). I had collected “statements” by nineteen Western artists, from Pollock to Jasper Johns, over a period of six months, but Rauschenberg, no matter how many telegrams I sent, did not reply. Finally, I settled on citing a quote by him from an old catalogue. But at last, after all this time, a thick envelope, fragrant with the dust of the American Southwest, arrived unexpectedly. As Rauschenberg mentioned in the letter, he seemed to have written the manuscript while touring with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Cunningham, alongside Martha Graham and José Limón, is a pioneer of American modern dance. In contrast to Graham’s work, already considered a classic, and Limón’s strong literary overtones, Merce’s dance is dedicated to the pursuit of abstract movements themselves, and his use of “randomness” in his choreography is considered a unique feature of his work. The latter is known to have resulted from the influence of John Cage, and Merce has recently assembled a radical crew, including Cage as music director, Tudor as pianist, and Rauschenberg as art director in charge of stage sets, costumes, and lighting. The sight of this entire crew climbing into a big Volkswagen bus and touring various places on the vast American continent has the character of an expedition of early pioneers; they could also be called a stagecoach of avant-garde gypsies. Moreover, in order to support Cunningham’s Broadway performance, his friend Jasper Johns established the Merce Cunningham Foundation, and painters and sculptors associated with the New York School and Pop art, including de Kooning, contributed their work for a benefit exhibition. What an enviable, moving story.

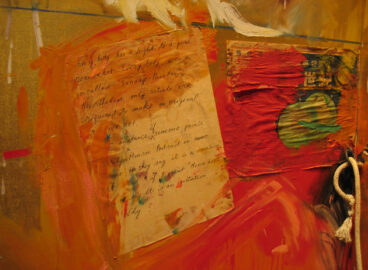

Late last year, I went to see the performance of these avant-garde gypsies. It was in Binghamton, a small city about three hundred miles from Manhattan. I climbed into Johns’s car with a pretty Swedish girl and finally made it to the performance after about a five-hour drive. The stage was a college auditorium in upstate New York, however, the dance of Cunningham’s company brimmed with an unparalleled, pure beauty. While Cage and Tudor tapped the piano strings and the bottom of the piano and made electrical sounds using their trademark technique, the dancers’ aggressive, elastic movements unfolded in an unsettling and disorderly manner as if to shatter the viewers’ conventional sense of rhythm. It was like a pillar of ice collapsing suddenly, or mysterious birds fluttering past. . . . There, after all form and literature were eliminated, “time” itself, as if it had assumed the shape of the physical body and movement, expanded endlessly before our eyes. Meanwhile, Rauschenberg added to this movement his costumes of red-and-black tights; a band of dangling, empty cans; braided elastic cords; and lighting that changed out of sequence. Sound, dance, and art—these three players, as opposed to the effeminate compromise of so-called “unity,” achieved a rare fusion by crashing into one another with naked antagonism. After the evening’s performance, I was in a daze as I sent Cunningham’s company off in their “stagecoach,” heading toward their next destination. By the time I reached New York City after driving for another five hours or so, it was nearly daybreak.

Now, let’s turn to Rauschenberg’s manuscript “Note on Painting” (October 31–November 2, 1963). As instructed in the letter, I respected his wishes and had the manuscript printed as is. The writing is very typical of him. While written in a seemingly extremely logical manner, it contains completely unrelated words that jump out among the others like alien objects. I will translate the opening section as an example.

I FIND IT NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE FREE ICE TO WRITE ABOUT JEEPAXLE MY WORK. THE CONCEPT I PLANTATARIUM [sic] STRUGGLE TO DEAL WITH KETCHUP IS OPPOED [author’s note: the s has been dropped from “opposed”] TO THE LOGICAL CONTINUITY LIFT TAB INHERENT IN LANGUAGE HORSES AND COMMUNICATION.

“Free ice,” “plantatarium [sic],” “ketchup,” “horses,” and “lift tab” are, presumably, words that Rauschenberg encountered along highways, at gas stations, and on signboards in cities as he traveled through Texas by bus. Writing the note inside the rattling bus, he lifted his eyes to look out and carelessly threw into his logical sentences any word that jumped out at him in that moment. As if to cut off the neat sequence of logic and grammar, the readymade words barge in with muddy feet. Here is the following section:

MY FASCINATION WITH IMAGES OPEN 24 HRS. IS BASED ON THE COMPLEX INTERLOCKING OF DISPARATE VISUAL FACTS HEATED POOL THAT HAVE NO RESPECT FOR GRAMMAR. THE FORM THEN DENVER 39 IS SECOND HAND TO NOTHING. THE WORK THEN HAS A CHANCE TO ELECTRIC SERVICE BECOME ITS OWN CLICHÉ. LUGGAGE. THIS IS THE INEVITABLE FATE FAIR GROUND OF ANY INANIMATE OBJECT FREIGHTWAYS.

Rauschenberg hates the word “collage,” and so he calls his works “Combines.” In these pieces, various objects—a pair of shoes, a ball, Coca-Cola bottles, signboards, old paintings, a stuffed goat and a chicken, even a bed and a ladder—appear. However, the result is different from the happy encounter of strange objects in the internal world that the Surrealists call “collage.” On the contrary, the objects in Rauschenberg’s work retain their heterogeneity and antagonism as they “combine” without any connection and exist contemporaneously. Even the paint in his work begins to look like one of the disparate objects. Instead of drawing materials toward himself and expressing something, he throws himself into the chaotic relationships found in reality and thereby establishes an alibi of identity. The situation is the same with this “note.” The note is different from Surrealist poems that uncover a new, internal world through the connection of illogical words. In the note, logic and readymade words, like paint and Coca-Cola bottles, exist side-by-side without ever meeting eye to eye. And if the point of Rauschenberg’s argument is to assert this contemporaneity, the logic, by existing at the same time as the readymade words that are the examples of his argument, is destroyed all the more vividly. Certainly, this deserves to be called a “Combine-Statement.” I invite the reader to read the rest by making your own “combines.”

About ten days after I received this manuscript, I heard the news of President Kennedy’s assassination. It also happened in Texas. Not far from where Rauschenberg had penned his “note” as he collected words from the road, the bullet of a single madman pierced through the brain of what had been a precarious symbol of peace. Faced with this strange “combine,” we are now left without any sense of what to do.

前衛の道摘録

公開質問会に出場する

大物中の大物、一九六四年のベネチア・ビエンナーレでの劇的逆転ホーマーで大賞をさらい、アメリカに初めてグランプリをもたらした戦後前衛画壇最大の若き巨匠ロバート・ラウシェンバーグが、ダンスのマース・カニングハムの美術監督として来日したのは、その年の年末近くだった。そして、それを機会に「ラウシェンバーグへの公開質問会」が開催された。

東京赤坂の草月会館ホールに集まった五百人あまりの、飢え切った育ち盛りの日本画壇予備軍の前で、オレンジ割りのウィスキーをがぶ飲みしながら、女性を混じえた三人のアシスタントといっしょに、ラウシェンバーグはどこから引っぱり出したのか日本人のぼくらもあまりお目にかかったことのない、伝統的日本画のタブローである六曲一双の金屏風に、ドリルを使って汗だくで挑戦中だ。

昭和三十九年一月、「反芸術、是か非か」の討論会で若者たちの間にセンセーションをまき起した批評家・東野芳明氏企画の第二回公開討論会である。

ラウシェンバーグといえば、彼の作品は原色版で、デビュー作、山羊の胸に自動車のタイヤを巻きつけ絵具をべたべたなすりつけた「モノグラム」をはじめ、ほとんどの作品が日本に紹介され、ぼくらにとってそのたびに、この斜陽の画壇に新しいファイトをみなぎらせる原動力となっていたのだ。とくに彼のハプニングをタブロー化したような既成オブジェ、たとえば扇風機、折れた交通信号、剥製の鳥などの大たんな使用は、もうこれ以上新しい作品は想像できないようなショックをぼくらに与えていたのだ。

その世界的な彼が、われわれの質問に答えようというのだから、嬉しくならないやつはバカだ。山のような質問をかかえ、むし暑い小さな草月会館ホールに集まった聴衆は、いまやおそしと薄暗い舞台を見まもった。

しかし、みんなのふくらんだ期待も簡単にふっ飛んだ。舞台で本番がいきなり始まり、集められたぼくらの、苦労してねん出し、選ばれたとっておきの質問は、会場の電話を通じて舞台横手の司会者・東野氏の席に送られたが、それはラウシェンバーグの耳に入るまでに、作曲家・一柳慧氏のブレーキングマシンなるものを通過せねばならず、その間めちゃめちゃに質問は分解され、サウンド化して場内に流れ出る始末。速記嬢二人をつれ、テープレコーダーを片手に張切っていた美術手帖編集部のA氏もこれにはお手あげだった。

しかしぼくは、ハリボテ作家・小島信明と顔を見合わせてにやっとした。こうなることは事前に知っていた。この質問会にぼくら二人は、作品で強烈に巨匠ラウシェンバーグにアッピールしてやろうと司会者東野氏と打合わせずみで、いまやおそしと、舞台の左そでに通訳の高階秀爾氏と机をかこみ、質問状を読み上げている東野氏のサイン「右手を二度あげる」を待っていたのだ。

その前日、じつはラウシェン一行の突然の訪問を受けていたのである。

イミテーションのOKをとる

がたがたとマンションの廊下をこちらへ近づいてくる一行の靴音に、ぼくの胸は高鳴った。何ったって、このいまや世界画壇で飛ぶ鳥をも落す勢いの、年齢的にもぼくと七つしか違わない人気画家。違うのは絵の値段だけだ。ボブ(ラウシェンバーグ)が一点二万ドル(約八百万円)平均、ぼくは二万円。しかしぼくもなすがままではいない。その年の十二月に新宿の椿近代画廊で行なう「グループ・レフト・フック」展(田中信太郎、小島信明、吉野辰海、坪内一忠とぼく)の出品が、ベランダ前の中庭にぞくぞくと誕生していた。なかでも大作はぼくの、椅子にすわっていても二メートル以上もあるハリボテの「思考するマルセル・デユシャン」の像。ぼくはそれを眺めながら思わず微笑んだ。やつらどんな顔をするだろう。

「カモン、プリーズ。」 靴のまま全員ダイニング・ルームに上がってもらい、すぐに飲み食いが始まる。ウィスキーのコップを片手に各自勝手に行動してもらう。食専門に酒専門、ときどき隣の日本間の、ぼくのおふくろの人形制作をまじめな顔でみつめている。 金ぶちのサングラスにカーキー色のジャンパー。およそ巨匠とは思えない、いかしたヤンキー。銀座のアイビー族が見たらすぐにでもマネしたくなるような着こなし、TPO (Time, Place, Occasion)満点といったところか。ウィスキーを離さないボブを連れ、ぼくは庭の作品解説だ。(しかし内心では、ぼくのイミテーション・アートを見て怒ってなぐりかかってくるのではないかと心配した。)

頭部を回転させる「思考するマルセル・デユシャン」の像を無言でみつめるボブ。前日ここを訪れたスエーデンの美術館長たちはこれを見て、頭の中に花火を仕掛けろなどと大騒ぎしたが、それとまったく対照的だ。

あくまでも無言のボブに、ぼくは次々と作品を見せて行った。ビートルズ、ラブリー・ラブリー・アメリカ、ドン・ショランダーと四つの金メダル、エアメール、これじゃあまるでアメリカン・ポップの再現だ。しかしさすが彼だ。 “もっと日本独自のものを見たい “などと腑抜けたことはぜったい言わない。彼にとって禅の国日本などどうでもよいのだろう。あるのはただ作品の対決だけだ。だからぼくがいかにポップ・アートに似ていようと、いやポップそのものであろうと、彼にとっては本国アメリカに新しく生まれつつあるニュー・アートとしての同じ緊張感と競争意識が燃え立つだけだ。

「メイ・アム・イミテート・ユア・ワークス?」

出た。取っておきの質問。ついでに例のコカコーラ・プランを見せようかと思ったが、勇気がない。どうせ明日の質問会で出せるだろう。

「ショーア。」

即座にOKの答えにぼくはひょうしぬけした。なぐられるか、少なくとも ちょっとした沈黙ぐらいはあってよさそうなもの。ようし、本人からOKを取ったんだからばんばんイミテーションしてやるぞ。だが結果は逆で、ボブとの会見以後、ぼくはイミテーション・アートに興味を失ってしまったのだ。

ラウシェンバーグ、質問に答えず

東野芳明氏の右手が二度上がった。よし出番だ!ぼくと小島は舞台の上にかけ上がり、かねてそでにかくしてあったデユシャンの像を、小島は例の旗かぶりの人形に「QUESTION」と大書した札をぶら下げて、中央に引っぱり出した。

質問1=拡大されたマリリン・モンローの顔は、ひげをつけられたモナリザ同様、一九一六年以来のダダイズム精神の流れを汲むものである。造形芸術におけるこのダダイズムの方法論は、いまや認められ価値を持ち、権威的資格を持ち、それはレジオンドヌール勲章と口ひげのごとく古く過去のものだ。ネオ・ダダイスト、ラウシェンバーグ氏よ、いかに。

質問2=もし貴殿の作品の隣に、まったく同じで、しかも十倍から五十倍に拡大され、強い効果を持つそれのイミテーション・アートが出現したとすれば、いかに。

質問3= 貴殿の作品は、非常に感覚的な効果、すなわちピカソのタブローのごとく、作者の天分である腕と筆先による魅力にひきつけられる。しかし秀れた感覚が秀 れた思想を現わすとはかぎらない。むしろ重要な思想を表現する場合、先天的異常感覚や病的資質はじゃまになるのではないか。廃物(交通標識、剥製の鳥、椅子、ベッド)に原色をドリッピングした貴殿のタブローに、ピカソ的な感覚にたよりすぎる画面の処理方法を感じてしまうが、いかに。

高階氏に訳してもらったぼくの質問を英語と日本語で読み上げる。ガソリンスタンド・マンのユニフォームを着たボブは黙々と制作するだけで、何と言われても絶対に答えない。ぼくの質問状を足もとにおいたら、その紙片まで屏風に貼りつけてしまった。

よし、では次だ。「思考するマルセル・デユシャン」にスイッチを入れる。ぎっこぎっこ始動し、スピードが増すにつれ、頭部だけまっ白に高速度回転する。すごい。聴衆の視線がいっせいにそれに集中する。ブラシを片手のボブが横目でこれをにらむ。

だがこれまで―—。 デユシャンの首がふっ飛びそうなのでスイッチを切る。何も起らない。ボブは制作をつづける。えんえん四時間半。幕だ。ついにべろべろになったボブはぼくを見て唐手の型で倒そうとする。そして最後までぼくの コカコーラ・プランを「マイ・サン」とかかえて離さなかった。

- 1Rauschenberg was the stage designer, not the art director, of the company.

- 2The machine is described as an electronic sound distorter in Hiroko Ikegami’s essay “Lost in Translation? ‘Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg.’ “

- 3Mr. A was an editor of the art journal Bijutsu Techō (Art notebook).

- 4The sculpture’s rotating head is driven by a motor.

- 5The work was created in 1964 and is now in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, Toyama.