One hundred years ago, Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White and Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Non-Objective Painting no. 80 (Black on Black) hung side by side in the Tenth State Exhibition in Moscow. Since that time, both paintings have made their way into the MoMA collection, and have been similarly displayed in the museum galleries. Art historian and curator Margarita Tupitsyn traces here a geneology of nonobjective painting in post-revolutionary Russia through the dynamic relationship of these two artists and their monochrome interventions.

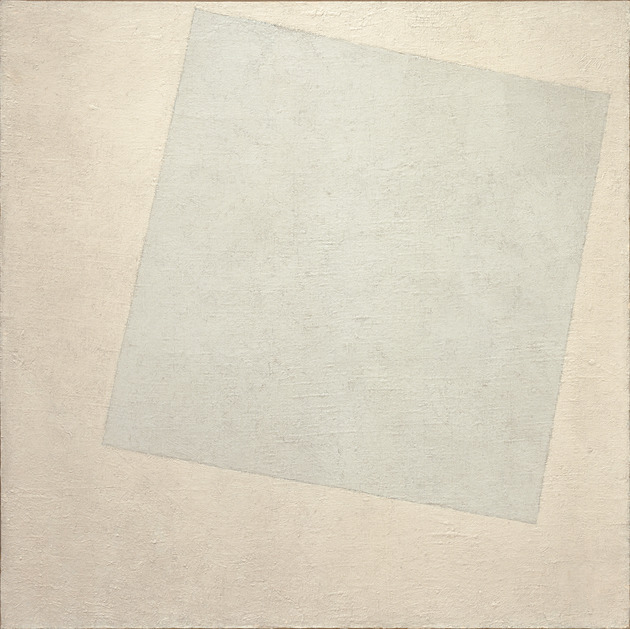

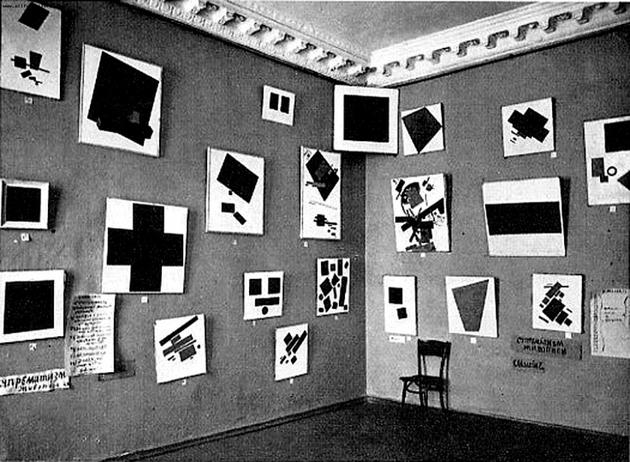

In the installation shots of past MoMA exhibitions dedicated to abstract art and the Russian avant-garde, Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White(1918) and Aleksandr Rodchenko’s Non-Objective Painting no. 80 (Black on Black)(1918), both in the Museum’s collection, are inseparable. The importance of MoMA’s exclusive opportunity to display these two paintings side by side, thus reconstructing “an original installation” from the Tenth State Exhibition: Nonobjective Creation and Suprematism (1919), is accentuated by Aleksandra Shatskikh in her book Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism (2012).1Aleksandra Shatskikh, Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012), 265. State exhibitions were organized by IZO Narkompros in Moscow between 1918 and 1921. Yet in the current hanging at MoMA, White on White and Black on Black (which are part of Malevich’s larger White on White series and Rodchenko’s Black on Black series, respectively) are split by Lyubov Popova’s Painterly Architectonic (1917), prompting a reexamination, on the centennial of the Tenth State Exhibition, of the relationship between white and black paintings, including their historical and cultural contexts.

Varvara Stepanova, whose diary is a unique source for this endeavor, assessed the Tenth State Exhibition as “a contest between Anti [Rodchenko’s pseudonym expressing his nonconforming stance] and Malevich. The rest is nonsense.”2See Katalog desiatoi gosudarstvennoi vystavki. Bespredmetnoe tvorchestvo i Suprematizm(Moscow: IZO Narkompros), 1919. Other participants included Aleksandr Vesnin—color compositions; Natalia Davydova—Suprematism; Ivan Kliun—Suprematism, color compositions, and nonobjective sculpture; Malevich—Suprematism; Mikhail Menkov—Suprematism and combination of light and color; Lyubov Popova—painterly architectonics from 1918 and prints from 1917; Aleksandr Rodchenko—Abstraction of Color, Discoloration. In total, the catalogue lists 220 works. In this categorical summation, she dismisses the other participants’ works, including her own, for the sake of the approbation of a black-and-white dialectic. Denying Rodchenko’s black paintings their own meaning, she adds, “Anti wanted to hang . . . his black things next to Malevich . . . so that these blacks do not go to waste.”3April 11, 1919, in Varvara Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda: pis’ma, poeticheskie opyty, zapiski khudozhnitsy (Moscow: Sfera, 1994), 71. All translations are by the author.

Malevich first used the term “nonobjective” in his brochure “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Painterly Realism” (1916), writing in advance of—but also as though about—his later white paintings: “I transformed myself in the zero of form and emerged from nothing to . . . nonobjective creation.” This endorsement of a ground-zero regime of painting amply corresponds to a post-revolutionary atmosphere marked by erasure of the toppled political system, including its cultural institutions. It also explains why the phrase “nonobjective creation” was adopted by avant-garde artists. Under this banner, which synthesized both a worldview and the role of experimentation in nonrepresentational art, they ascertained their identity in the newly established state.

This broader and more politically potent meaning of post-revolutionary nonobjectivism, which in turn implies that painting was near its exhaustion, was endorsed by Stepanova after the opening of the Tenth State Exhibition. “Nonobjective creation,” Stepanova wrote, minimizing (like Malevich) the use of the word “art,” “is not only a movement or a tendency in painting, but also a new ideology born to destroy philistinism of spirit, and maybe it is not for the social system, but for the anarchic one and an artist’s nonobjective thinking is not limited to his art, it enters his entire life, and under its flag all his needs and tastes proceed.”4January 7, 1920, in Ibid., 92. Stepanova’s reading of nonobjectivism as a synthesis of formalism and politics promises a means of identifying an alternative subject for post-revolutionary nonobjective practice in general, and for the white and black paintings in particular.

Malevich and Rodchenko produced their respective series between mid-1918 and the beginning of 1919, a period of violent social and political ruptures in modern Russian history. The October Revolution, World War I, in which Malevich served, and the outbreak of the Russian Civil War, made it impossible for the two artists to remain nonpartisan. Avant-garde literature has routinely positioned the two as supporters of the Bolshevik regime.5Nina Gurianova makes an important distinction between Moscow and Petrograd artists’ reactions to the Bolshevik Revolution, stressing that, unlike the former, the latter instantly identified with its agenda. Nina Gurianova, “‘Deklaratsiia prav khudozhnika’ Malevicha v kontekste moskovskogo anarkhizma 1917–18 godov,” http://hylaea.ru/pdf/malevich-anarchist.pdf. However, as Stepanova suggested, the theoretical basis of post-revolutionary nonobjectivism may in fact be rooted in anarchist aspirations, which is indeed confirmed in Rodchenko’s first contribution to the newspaper Anarchy: “We are coming to you, beloved comrades, anarchists, instinctively recognizing in you our hitherto unknown friends . . . The present belongs to artists who are anarchists of art.”6Aleksandr Rodchenko, “Tovarishcham anarkhistam,” Anarkhiia, no. 29 (March 28, 1918), cited in Russian Dada, 1914–1924, ed. Margarita Tupitsyn (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2018), 232. The section “Creation,” established in Anarchy for artists’ writings, avoided old terminology associated with fine art, and in this, went against the newly established Department of Visual Art in Narkompros (under the People’s Commissariat for Education) established on January 29, 1918. The title “Creation” specified that the true objective of contributors Aleksei Gan, Malevich, Aleksei Morgunov, Rodchenko, and Nadezhda Udal’tsova was to defend artists’ rights to freedom of expression, which they felt were equally threatened by the prerevolutionary institutions and the newly established commissariats. Their goal was to achieve unmediated creations that would replace any form of “prostituted”7Alfred Barr, “The LEF and Soviet Art,” Transition, no. 14 (Autumn 1928), 267. art. Above all, they thought, artists should pursue their own revolutions against artistic conventions and restrictive institutions. The Soviet government’s later repressive cultural policies proved that this early concern with freedom of expression was prolifically critical.

Manifesto-style texts such as Rodchenko’s “To Artists-Proletarians” and “Be Creators!,” and Malevich’s “Declaration of Artist’s Rights,”8For more on this essay, see Gurianova, “‘Deklaratsiia prav khudozhnika.’” all three of which were written for Anarchy, positioned artists as an oppressed and enslaved class akin to that of the proletariat. Rodchenko’s terminology, including “creator-rebel” and “revolution-creation,” radicalized the creative process and shifted it from an isolationist practice to a socially active one. Malevich’s text is more concerned with practical aspects such as the protection of artists’ work spaces and their right to maintain control over profits from sold art. Malevich preferred public collections to private ownership.

Equally oppressive for both Malevich and Rodchenko was the view held by some critics at home and abroad that Russian modernists “imitate[ed] the West!”9“To ‘Original’ Critics and the Newspaper Ponedelnik,” Anarchy, no. 85 (June 15, 1918), cited in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko: Experiments for the Future, Diaries, Essays, Letters, and Other Writings (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 83. Malevich’s term “Suprematism,” coined to describe flat geometric painting, encodes an assertion of originality and preeminence over Western movements.10Unveiled in the seminal 0, 10 exhibition in 1915, it rivaled Vladimir Tatlin’s counter-reliefs that started off the first phase of Russian Constructivism. Yet some nonobjectivists, including Rodchenko and Stepanova, resisted Malevich’s claim for “supremacy” in nonobjective circles by reason of suspecting him of mysticism,11Aleksei Gan, a future theorist of Constructivism, defended Malevich against other artists accusing him of mysticism. See January 11, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet’ bez chuda, 65. and they were unwilling to accept his Black Square (1915) as their trademark. However, Rodchenko’s desire to free himself from the cultural bondage of the West outweighed this kind of issue with Malevich, as he realized that cooperating with him would guarantee the formation of “an entirely original identity in Russia’s art” and position them as “the first inventors of the new, as yet unseen in the West.”12“To ‘Original’ Critics and the Newspaper Ponedelnik,” 83. Pledging to be Russia’s “own art,” and thus a national style, it asserted a competition with the West and, significantly, declared a position of difference from a Bolshevik internationalism that is embodied in, for instance, Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (1920).

Initially viewing the anarchist groups as allies in the fight against the old regime, by the summer of 1918, the Bolsheviks were ready to dissolve them and their critical forum Anarchy.13This coincided with the assassination of the tsar and his family on July 16, 1918. Shatskikh dates “the emergence of white Suprematism” from this time.14Aleksandra Shatskikh, Black Square, 260. This means that Suprematism was conceived when Malevich could no longer write for Anarchy, and when the possibility of a “working anarchism” had dissolved. A retreat to “pure anarchism,” that is, “abstract, utopian, and realized only on paper,”15Gurianova, “’Deklaratsiia prav khudozhnika,’” was the only remaining option. White paintings were as pure and nonconventional within the conventions of modernist painting as Malevich could come up with. He succeeded in producing a work “as yet unseen in the West.”16January 11, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet’ bez chuda, 65. He also constructed a visual metaphor of an unmediated, autonomous creativity, which he had defended in Anarchy. But the subject of white paintings is additionally discernable from Malevich’s text “Declaration I,” written on June 15, 1918, around the time Malevich executed them. In this text, he describes the current state of Suprematism as a blend of formal and political concepts—a “Suprematist federation of colors of colorlessness,” and a “new symmetry of social paths;”17Kazimir Malevich, “Deklaratsiia I,” in Krasnyi Malevich: stat’i iz gazety ‘Anarkhiia’ (Moscow: Common Place, 2016), 213. and he sees “socialism illuminating its freedom to the world,” and “Art falling in the face of Creativity.”18Ibid., 217. The result is a fervent socio-formalist concoction that, mirrored in white Suprematism, once again positions art and creativity as opposing concepts: the former systemic and institutional, the latter unmediated and under artists’ control.

This new model of post-revolutionary Suprematism—and the creation of White on White—was Malevich’s act of spite toward Black Square, a trademark of pre-revolutionary Suprematism that had begun to alienate him from the Moscow nonobjectivists. In White on White, Malevich bleached Black Square, turning it into a pale shadow hardly distinguishable from its white background. The remaining black outlines around the square function as a referent to the subject of contention. Skewed, and edged closer to the picture frame, White on White upsets the steely stability of Black Square, moving toward new borders that are beyond painting.

By the end of 1918, Rodchenko had definitely seen Malevich’s white paintings. He wrote, “Malevich paints without form and color. The ultimate abstracted painting. This is forcing everyone to think long and hard. It’s difficult to surpass Malevich.”19December 25, 1918, in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 88. Rodchenko’s statement confirms his acceptance of Malevich as a guru of “the new,” and an artist who is hard to outdo—and with whom he himself now wanted to collaborate. “Malevich and I decided to write and publish as much literature as possible,”20January 1, 1919, in ibid. he wrote regarding the content of the catalogue for the Tenth State Exhibition. Rodchenko’s genius lay in realizing that all he had to do was invert Malevich’s new creation: to come up with a concept that, together with Malevich’s series, would construct the dialectical condition rife with overcoming negation. With this in mind, Rodchenko flung himself into hyper production, and by New Year’s Day, 1919, he had done “[a]bout twenty-nine to thirty new pieces.”21January 1, 1919, in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 88.

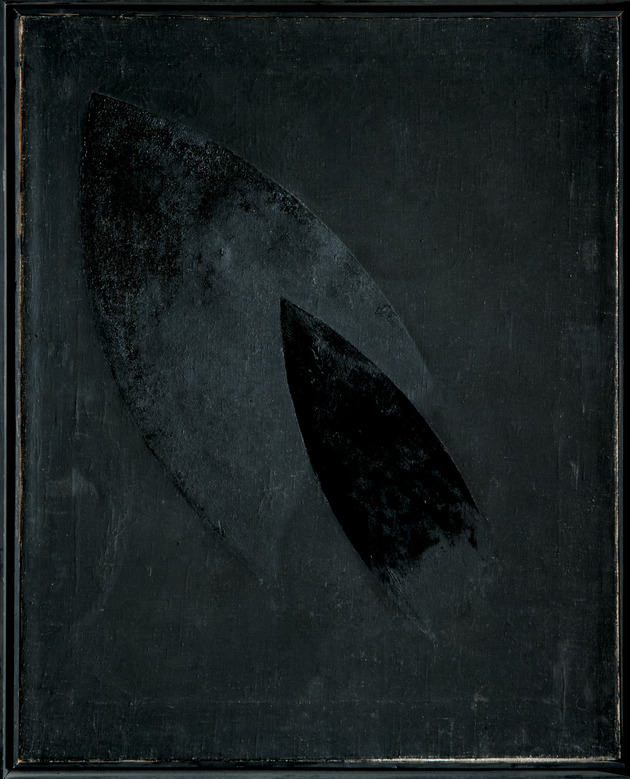

Rodchenko painted Black on Black during this marathon, yet he commenced his contest with Malevich with a retort not to White on White, but rather to Black Square. This made White on White a dialogical painting, synthesizing nonobjectivists’ voices of discontent toward this passionately debated canvas as anti-painting, as “nothing,”22Coincidently, Rosalind Krauss writes about Malevich’s abstraction in terms of the ability “to paint Nothing,” the condition of an ultimate liberation and purification reflected in Malevich’s white paintings. Rosalind E. Krauss, “Reading Jackson Pollock, Abstractly,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths(Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1985), 237. “philosophy of a square,” “a graphic scheme.”23January 11, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 67. Rodchenko ignored Malevich’s defensive warning that it would be impossible to avoid the square’s effect, and “destroys”24April 10, 1919, in ibid., 88. it by swirling its shape, rounding it off, and replacing the Suprematist trademark with a circle. Rodchenko turns Malevich’s “color realism” —“a smooth coloring in one paint”25Ibid.—into “painterly confusion,”26Kazimir Malevich, “Suprematism,” in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902–1934, ed. John Bowlt (New York: Viking Press, 1976), 144. destroying the divided positions that the black and white colors have in Black Square. His palette in Black on Black reverberates his excitement about being able to buy “a few tubes of marvelous oil paints, including “black, ocher . . . whites,”27December 15, 1918, in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 87. luckily obtained amid the “constant looking for food”28December 1, 1918, in ibid. that was necessary during the Civil War. The fortunate abundance of painting materials (Rodchenko also obtained fifteen stretchers) resulted in an “exhaustion from painting” that Rodchenko described as “the most pleasurable thing.”29December 15, 1918, in ibid., 88. Black on Black exudes, to paraphrase Roland Barthes, “the pleasure of the painting.”

Yet some sections of this work contradict this kind of painterly sensation; these are covered with an unmodulated, dull black color, at times applied thickly, and like Black Square, full of craquelures. It is this “most unthankful”30April 10, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 88. form of the color black at which, to rephrase Rodchenko, color and brushwork die, that he employs in order to create the ultimate color reverses to Malevich’s White on White paintings. These are monochromatic compositions nos. 81, 82, and 84, for which the collective title Abstraction of Color and Discoloration, under which Rodchenko listed his black-on-black series in the Tenth State Exhibition’s catalogue, is particularly apt. Rodchenko describes them as “Black on Black. Elaboration of one color by means of different surface conditions. Destruction of color for the same material treatment of monotonality.”31“A Laboratory Passage Through the Art of Painting and Constructive-Spatial Forms Toward the Industrial Initiative of Constructivism,” in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 126. These canvases lack painterliness and gesticulation, and they offer no visual pleasure. They are not photogenic. The color black is a priori more aggressive than white, and perhaps this is why Rodchenko compensates this cold color with warm forms of “ovals, circles, ellipses”32Aleksandr Rodchenko, “The Dynamism of Planes,” in ibid., 83. (similar shapes, can be found in Malevich’s white paintings now in the collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam).

Black-on-black’s antagonistic aura served “Anti” well in his anti-Western agenda and also in his goal to create an artwork that no one would deem an imitation of Western art. Stepanova affirms Rodchenko’s success, saying that he “gave in the ‘blacks’ what the West has dreamt about, a true easel painting brought to the last point . . . one can now speak about new painterly realism.”33April 10, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 89. “The peculiarly Russian conceptions of faktura [texture],”34Margit Rowell, “Vladimir Tatlin: Form/Faktura,” October 7 (Winter 1978): 83. which preoccupied many leading avant-gardists in Russia, played a role in Rodchenko’s achievement. In fact, Malevich’s indifference to the effects of faktura was another reason why nonobjectivists criticized his work. This continued with the White on White series that, to them, lacked textural interest. Instead of painting, they said, Malevich covered works in paint. In contrast, in the black paintings, Rodchenko charted gradations within a single color by rendering it “shining, matt, faded, rough, smooth.”35April 10, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 89. This “triumphed”36Ibid. faktura, and created a more complex relationship with the viewer. Stepanova observed that during the Tenth State Exhibition, “More serious [viewers] were less resentful of the black [paintings], which they perceived as something particularly abstract or maybe they simply did not see them.”37January 7, 1920, in ibid., 90. Presumably, viewers were not always able to focus on the black paintings due to the lack of familiar pictorial characteristics, in the absence of which, the paintings merged into actual space, revealing the objectness (predmetnost) of nonobjective forms and alluding to the end of painting.

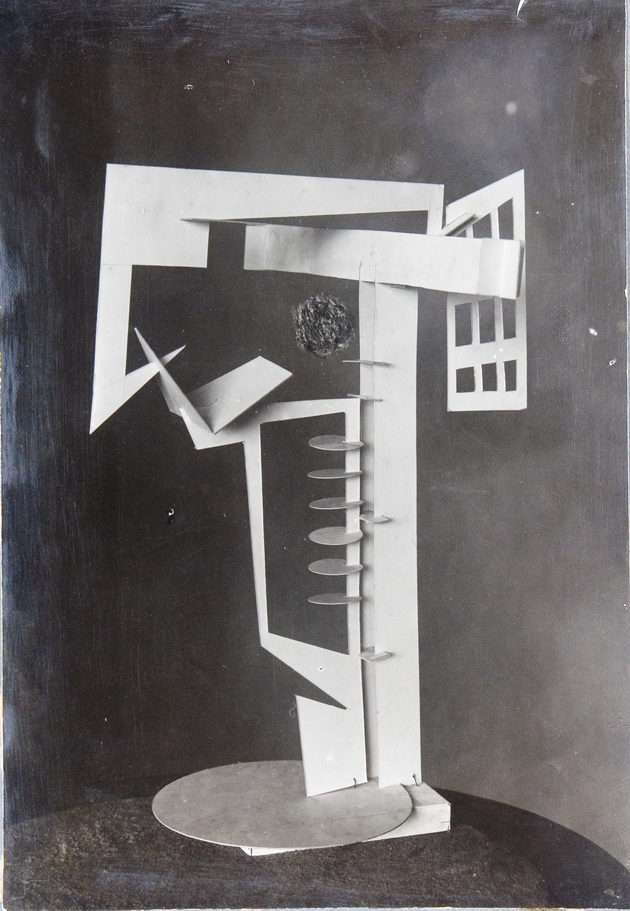

Unlike Malevich’s White on White series that I earlier referred to as an allegory of autonomous practice, the Black on Black paintings were not. This is because they were conceived within the logic of supplementarity in relation to White on White paintings. However, while making many black canvases, Rodchenko also conceived of his own example of pure anarchic creation. These are white sculptural objects, described as Assembled and Disassembled, that originated Rodchenko’s three series of “spatial constructions” and launched the laboratory period of Constructivism. It is conceivable that in his Assembled and Disassembled objects, Rodchenko was reacting to Malevich’s non-geometric and even non-Suprematist forms, which are rendered in a different shade of white (I am again referring to the paintings from the collection of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam), this time recognizing the sculptural potential he fulfilled before Malevich made his “architectons” (1920). Stepanova describes Rodchenko’s state of joissance from process rather than product: “Anti is constructing sculpture, he loves it . . . it takes nothing for him to break everything and make the most amazing thing again. . . . he is so confident in the power of his creativity.”38March 6, 1919, in ibid., 80. For Rodchenko, the “game”39Ibid. (his expression) of the materialization and dematerialization of an aesthetic object raised the degree of creative anarchism that he and Malevich propagated in their writing for Anarchy. Their shared platform of anarchist utopia allowed them to reconcile their differences with regards to nonobjective practice, establishing a dialectical and agonistic relationship. Malevich seemed to agree that the two-color match ended in a draw. “We should appear together,”40April 10, 1919, in ibid., 90. he proposed to Rodchenko after the exhibition’s opening.

Rodchenko’s comrade Osip Brik, a formalist critic and editor of the newspaper Art of the Commune, visited the Tenth State Exhibition and, according to Stepanova, the “‘Blacks’ brought [him] into amazement.”41Ibid. Perhaps Brik’s keen, leftist eye (brilliantly conceptualized by Rodchenko in an unpublished cover of LEF in 1924), observed a looming transition from faktura to factography in Rodchenko’s black paintings.42I am referring to Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October 30 (Autumn 1984): 82–119. In this respect, it is interesting to note that Jay Leyda, a film specialist, owned Rodchenko’s Non-Objective Painting no. 80 (Black on Black), and Aleksei Gan, who defended Malevich in the debates with nonobjectivists, was the first to illustrate Rodchenko’s sculptures in his magazine Kino-fot, no. 2 (1922), under the heading “Cine-Avant-garde.” For further discussion of Rodchenko’s transition from painting to prints and photography, see Margarita Tupitsyn, “Colorless Field: Notes on the Paths of Modern Photography” in The Museum of Modern Art website, Object:Photo: Modern Photographs, 1909–1949: The Thomas Walther Collection http://www.moma.org/ interactives/objectphoto/assets/essays/Tupitsyn.pdf Indeed, his later street photography, such as the series of images of the Building on Miasnitskaia Street (1925), the Brianskii Railway Station (1927), and Pine Trees (1927), filled Rodchenko with an unbounded sense of independence and creative freedom, as he wandered the streets of Moscow, climbed rooftops, and lay on the ground in resistance to photography’s conventional belly-button perspective. On becoming a commissioner of SVOMAS (Free state art studios), where Malevich already had a studio, Brik invited Rodchenko to join. For both artists, the school’s agenda of “maximum freedom for artists,”43Anatoly Lunacharsky, cited in Velikaia utopiia:russkii i sovetskii avangard, 1915–1932(Moscow: Galart, 1993), 710. the availability of work space, and the independent teaching curriculum, complemented their model of liberation from institutional constraints, middlemen, and anxiety over the production and distribution of art objects. “Nonobjective painting has left the museums, it is—the street, the square, the city and the entire world,”44“Everything is Experiment,” in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 93. asserted Rodchenko in 1920. With this statement, he reaffirms Malevich’s craving for an objectless avant-gardism, which the latter expressed two weeks after the Revolution, when he said: “I decided to declare myself the chairman of space. It makes me at ease, withdraws me, and I breath freely.”45Malevich to Mikhail Matiushin, 10 November 1917, in Malevich o sebe, sovremenniki o Maleviche. Pis’ma. Dokumenty. Vospominaniia. Kritika, eds. I. A. Vakar and T. N. Mikhienko, 2 vols. (Moscow: RA, 2004), 1:107. Such a fantasy of nonobjective creation without borders was also invested into the white and black series, making them a symbol of the gap between what Malevich and Rodchenko had imagined and what the Bolshevik apparatus was preparing for them.

- 1Aleksandra Shatskikh, Black Square: Malevich and the Origin of Suprematism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012), 265. State exhibitions were organized by IZO Narkompros in Moscow between 1918 and 1921.

- 2See Katalog desiatoi gosudarstvennoi vystavki. Bespredmetnoe tvorchestvo i Suprematizm(Moscow: IZO Narkompros), 1919. Other participants included Aleksandr Vesnin—color compositions; Natalia Davydova—Suprematism; Ivan Kliun—Suprematism, color compositions, and nonobjective sculpture; Malevich—Suprematism; Mikhail Menkov—Suprematism and combination of light and color; Lyubov Popova—painterly architectonics from 1918 and prints from 1917; Aleksandr Rodchenko—Abstraction of Color, Discoloration. In total, the catalogue lists 220 works.

- 3April 11, 1919, in Varvara Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda: pis’ma, poeticheskie opyty, zapiski khudozhnitsy (Moscow: Sfera, 1994), 71. All translations are by the author.

- 4January 7, 1920, in Ibid., 92.

- 5Nina Gurianova makes an important distinction between Moscow and Petrograd artists’ reactions to the Bolshevik Revolution, stressing that, unlike the former, the latter instantly identified with its agenda. Nina Gurianova, “‘Deklaratsiia prav khudozhnika’ Malevicha v kontekste moskovskogo anarkhizma 1917–18 godov,” http://hylaea.ru/pdf/malevich-anarchist.pdf.

- 6Aleksandr Rodchenko, “Tovarishcham anarkhistam,” Anarkhiia, no. 29 (March 28, 1918), cited in Russian Dada, 1914–1924, ed. Margarita Tupitsyn (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 2018), 232.

- 7Alfred Barr, “The LEF and Soviet Art,” Transition, no. 14 (Autumn 1928), 267.

- 8For more on this essay, see Gurianova, “‘Deklaratsiia prav khudozhnika.’”

- 9“To ‘Original’ Critics and the Newspaper Ponedelnik,” Anarchy, no. 85 (June 15, 1918), cited in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko: Experiments for the Future, Diaries, Essays, Letters, and Other Writings (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2005), 83.

- 10Unveiled in the seminal 0, 10 exhibition in 1915, it rivaled Vladimir Tatlin’s counter-reliefs that started off the first phase of Russian Constructivism.

- 11Aleksei Gan, a future theorist of Constructivism, defended Malevich against other artists accusing him of mysticism. See January 11, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet’ bez chuda, 65.

- 12“To ‘Original’ Critics and the Newspaper Ponedelnik,” 83.

- 13This coincided with the assassination of the tsar and his family on July 16, 1918.

- 14Aleksandra Shatskikh, Black Square, 260.

- 15Gurianova, “’Deklaratsiia prav khudozhnika,’”

- 16January 11, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet’ bez chuda, 65.

- 17Kazimir Malevich, “Deklaratsiia I,” in Krasnyi Malevich: stat’i iz gazety ‘Anarkhiia’ (Moscow: Common Place, 2016), 213.

- 18Ibid., 217.

- 19December 25, 1918, in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 88.

- 20January 1, 1919, in ibid.

- 21January 1, 1919, in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 88.

- 22Coincidently, Rosalind Krauss writes about Malevich’s abstraction in terms of the ability “to paint Nothing,” the condition of an ultimate liberation and purification reflected in Malevich’s white paintings. Rosalind E. Krauss, “Reading Jackson Pollock, Abstractly,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths(Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1985), 237.

- 23January 11, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 67.

- 24April 10, 1919, in ibid., 88.

- 25Ibid.

- 26Kazimir Malevich, “Suprematism,” in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902–1934, ed. John Bowlt (New York: Viking Press, 1976), 144.

- 27December 15, 1918, in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 87.

- 28December 1, 1918, in ibid.

- 29December 15, 1918, in ibid., 88.

- 30April 10, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 88.

- 31“A Laboratory Passage Through the Art of Painting and Constructive-Spatial Forms Toward the Industrial Initiative of Constructivism,” in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 126.

- 32Aleksandr Rodchenko, “The Dynamism of Planes,” in ibid., 83.

- 33April 10, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 89.

- 34Margit Rowell, “Vladimir Tatlin: Form/Faktura,” October 7 (Winter 1978): 83.

- 35April 10, 1919, in Stepanova, Chelovek ne mozhet zhit’ bez chuda, 89.

- 36Ibid.

- 37January 7, 1920, in ibid., 90.

- 38March 6, 1919, in ibid., 80.

- 39Ibid.

- 40April 10, 1919, in ibid., 90.

- 41Ibid.

- 42I am referring to Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, “From Faktura to Factography,” October 30 (Autumn 1984): 82–119. In this respect, it is interesting to note that Jay Leyda, a film specialist, owned Rodchenko’s Non-Objective Painting no. 80 (Black on Black), and Aleksei Gan, who defended Malevich in the debates with nonobjectivists, was the first to illustrate Rodchenko’s sculptures in his magazine Kino-fot, no. 2 (1922), under the heading “Cine-Avant-garde.” For further discussion of Rodchenko’s transition from painting to prints and photography, see Margarita Tupitsyn, “Colorless Field: Notes on the Paths of Modern Photography” in The Museum of Modern Art website, Object:Photo: Modern Photographs, 1909–1949: The Thomas Walther Collection http://www.moma.org/ interactives/objectphoto/assets/essays/Tupitsyn.pdf

- 43Anatoly Lunacharsky, cited in Velikaia utopiia:russkii i sovetskii avangard, 1915–1932(Moscow: Galart, 1993), 710.

- 44“Everything is Experiment,” in The Museum of Modern Art, Aleksandr Rodchenko, 93.

- 45Malevich to Mikhail Matiushin, 10 November 1917, in Malevich o sebe, sovremenniki o Maleviche. Pis’ma. Dokumenty. Vospominaniia. Kritika, eds. I. A. Vakar and T. N. Mikhienko, 2 vols. (Moscow: RA, 2004), 1:107.