In the introduction to the 1992 Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair catalogue, the organizers of the event predicted that art in China would turn toward the market, that commercial investment would replace state sponsorship, that commercial enterprises would replace state-sponsored cultural organizations, and that a new system of legitimization and value based on academic criteria, legal contracts, and monetary reward would replace the bureaucratic and often compromised judging process favored by the state.1See May 11, 1992, preface to the catalogue for the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair, unpaginated. The catalogue’s Chinese title is Zhongguo Guangzhou shoujie jiushi niandai: yishu shuangnianzhan youhua bufen zuopin wenxian. Please note that the term “Art Fair” does not appear in the Chinese title of this catalogue, only in the original English title, which is The First 1990s’ [sic] Biennial Art Fair Guangzhou, China, Oil Painting Section, Documentary Works. For the purpose of this essay, the authors have standardized the English title of the exhibition.

These were bold claims at a time when there was almost no commercial market for Chinese contemporary art. And they were backed up by a bold experiment—an exhibition of work by more than 350 artists, most of whom were under the age of forty. All of the artwork in the exhibition was available for sale, and, in addition, the artists who made the top twenty-seven artworks, as judged by a youthful group of jurors, were eligible to receive large cash rewards.2Critics involved in the selection of the work included Zhu Bin, Shao Hong, Yi Ying, Yuan Shanchun, Pi Daojian, Peng De, Yang Li, Huang Zhuan, and Yin Shuangxi. See Lü Peng, Zhongguo dangdai yishushi, 1990–1999 [A history of modern Chinese art: 1990–1999], 127. These awards ranged from 10,000 RMB for third place to 50,000 RMB for first place, an extraordinary amount of money at a time when few Chinese citizens made more than 3,000 RMB a year.3See “Guangzhou shoujie jiushi niandai yishu shuangnianzhan youhua bufen huojiang zuopin fenggao” [Announcement of the award-winning artwork of the First 1990s’ Guangzhou Biennial, Oil Painting Section], Yishu shichang [Art and market], no. 6 (1992): 67. Also see World Bank GPD per capita statistics, accessed February 28, 2015, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.CD?page=4

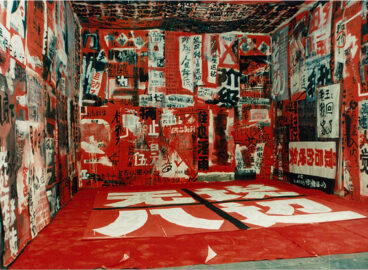

Called the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair (“Art Fair” is missing from the Chinese title), this exhibition took place in a hotel in the southern Chinese capital of Guangdong Province from October 8 to October 28, 1992.4See Lü Peng, interview by author, Chengdu, October 16, 2006. Also see numerous primary documents in the Lü Peng Archive at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, including the invitation card, exhibition application, sponsorship documents, contracts, jury statements, press material, and photographs. It was launched with start-up funds provided by a Chengdu-based entrepreneur whose company made car parts, and its goal was to make a profit.

The Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair was prescient. It foresaw the development of an active art market for contemporary Chinese oil painting. It anticipated the art fairs and their not-so-distant cousins, the domestic biennials that sprang up all over China and other parts of Asia in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But it also launched a virulent debate that continues to this day.

Did the art market offer contemporary artists a credible alternative to the state system of control in the wake of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen tragedy, when experimental art was barred from most government-sponsored venues and media platforms? Did this alternative system open a new space for legitimization of and support for artists looking for independence and a measure of personal freedom? Or was commerce a contaminant that lured artists with the promise of short-term financial rewards, sapping art of its criticality and edge, as many critics have contended, then and now? Did it strengthen the hands of foreign buyers with their greater purchasing power, thus unduly influencing artistic taste and trends?

By most accounts, the experiment failed to achieve its goals. From the perspective of today, the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair could be construed as an overly literal response to Deng Xiaoping’s call to accelerate economic reform after his famous 1992 tour of southern China, which has been encapsulated in the catchphrase “To get rich is glorious.”5That Deng Xiaoping, preeminent leader of the People’s Republic of China from the 1970s to the 1990s, said “To get rich is glorious” has never been confirmed. But the phrase has frequently been used in the press and particularly among Western writers to describe the ethos of entrepreurship that was encouraged by the Chinese state and developed in the wake of a series of economic reforms that began in the late 1970s and accelerated through the 1980s and 1990s. Even one of the main organizers, Chengdu-based art writer and cultural entrepreneur Lü Peng, has admitted that his goals were unrealistic, even naive. The timing was premature, the structure of the project was flawed, and the company that provided its main support went bankrupt.6With start-up funds provided by entrepreneur Luo Haiquan, the Xishu Art Company was established to fund the operations of the Guangzhou Biennial. However, when expenses exceeded the overly optimistic revenue projections, the Xishu Art Company was unable to meet its obligations, resulting in a lawsuit. See page 248, Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market: Chinese Contemporary Art in the Post-Mao Era, and documents in the Lü Peng Archive at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong. Its prematurity and flawed execution aside, the exhibition’s basic premise was resisted by many in the art world. Contemporary artists created performances to express their displeasure. Two participants sprayed Lysol throughout the exhibition to disinfect the “contaminated” space.7See Wang Lin, Zhongguo: Bajiuhou yishu [China: Post-’89 art]. (Hong Kong: Yishu chaoliu zazhishe,1997): 92. Another distributed bogus shares in a commercial art company named after himself.8See “Sun Ping gupiao youxian gongsi zai Guangzhou faxing gupiao” [Sun Ping Company issues shares in Guangzhou], Guangdong meisujia [Guangdong artists], no. 2 (1993): 49. And preeminent art critic Li Xianting reportedly became so disturbed after attending the opening event that he wept.9See Wang Lin, Zhongugo: Bajiuhou yishu [China: Post-’89 art]. (Hong Kong: Yishu chaoliu zazhishe,1997): 92–93. Other criticisms were aimed at the Biennial’s provincialism. Many of the participants, including the organizers, judges, and artists came from the southern and southwestern provinces of China, a bias that some critics saw as unbalanced and limiting.10Yi Ying, “Chao weiping feng zhaqi,” [The wind picks up when the tide is still in]. Beijing qingnianbao [Beijing youth daily], October 15, 1992, 4–5. Also see Geremie Barmé, “Artful Marketing”, In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999): 218.

However, there were certain central issues that most young critics agreed upon. First, it was time to establish an alternative system of legitimization of and support for contemporary art, one based on critical and academic analysis rather than on bureaucratic and political credentials required by the state. And second, as Lü Peng asserted in a 1992 article in the magazine Art and Market, this alternative system and the standards underlying its voracity should be determined by the Chinese people themselves.11See Lü Peng “Biaozhun bixu you Zhongguoren ziji lai que ding” [Standards should be established by Chinese people themselves], Yishu shichang, no. 7 (1992): 18–19. China’s state-sponsored cultural apparatus was stifling and the hyper-conservatism of the prevailing standards of politically correct art were a constant irritant. Nevertheless, in the minds of these idealists, the emergence of buyers from outside China was also irritating, as they were considered equally misguided, patronizing artists many young critics deemed unworthy.12See Ye Yongqing “Zhiyou Zhongguo ren caineng zujin Zhongguo yishu shichang de jianli: Yishujia Ye Yongqing 1991 nian 9 yue 12 ri gei Lü Peng de xin” [Only Chinese people can establish a Chinese art market: A letter to Lü Peng from Ye Yongqing dated September 12, 1991], Yishu shichang, no. 2 (1991): 3.

Criticizing foreign patronage of the arts was not new. As early as 1979, then–Chairman of the Chinese Artists Association Jiang Feng inveighed against the degrading influence of foreign buyers on the production of artists who, he wrote, were churning out inferior works in pursuit of material gain.13See Jiang Feng, “Guanyu Zhongguohua wenti de yifeng xin” [A letter about the problem of Chinese painting], Meishu [Art], no. 12 (1979): 10–11. Although not the first to identify these pernicious tendencies, the organizers of the Guangzhou Biennial were among the first to attempt to construct a serious domestic system of support for experimental art, one based on domestic financial support and patrons, a domestic legal structure and contracts, and standards determined by local professionals, in particular young academicians and critics.

These aspirations, which were at once professional and nationalistic, again anticipated the development later in the decade. For example, Zhang Qing in the preface of the catalogue of the 2000 Shanghai Biennale railed against “patrons from embassy districts and galleries hosted by foreigners” who “exerted a strong aesthetic influence on local artists who were kept busy producing lucrative ‘new paintings for export’ with amazing speed and quantity.”14Zhang Qing, “Beyond Left and Right: Transformation of the Shanghai Biennale, ” Shanghai Biennale 2000, unpaginated. In this preface Zhang also expressed heightened concerns about the international biennale circuit that had developed apace during the 1990s and worried that if the Chinese did not take action, “the yardstick . . . for admission would be held exclusively in foreign curators’ hands.”15Zhang Qing, “Beyond Left and Right: Transformation of the Shanghai Biennale,” Shanghai Biennale 2000, unpaginated. In Zhang’s mind the 2000 Shanghai Biennale was a serious attempt, like the Guangzhou Biennale had been eight years before, to “reshape the existing exhibition system,” and to develop critera determined by Chinese (and Asian) scholars.16Zhang Qing, “Beyond Left and Right: Transformation of the Shanghai Biennale,” Shanghai Biennale 2000, unpaginated.

In hindsight, that the Guangzhou Biennale failed to achieve its unrealistic aspirations is understandable. The disparity in purchasing power between China and other industrialized countries was, in the 1990s, too great to overcome, such that, along with the exorable wave of global capital, Chinese products including art were swept offshore to Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the wealthier West. And it is only now, in the 2010s, that this tide might be turning, at least in the art world.17If the price of art at auction can be used as a yardstick, in at least one study, sales in China of contemporary art at auction surpassed the U.S. art market, totaling 601 million euros in 2014, versus 552 million euros in the U.S. See Contemporary Art Market 2014: The Artprice Annual Report, 21, accessed February 28, 2015, http://imgpublic.artprice.com/pdf/artprice-contemporary-2013-2014-en.pdf But despite its multiple failures, the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair did anticipate the importance of the role of the burgeoning art market in the development of contemporary Chinese art and succeeded in offering some experimental artists (mostly painters working in oil) an alternative to the state system of support that had previously controlled art’s production, circulation, and value. In this regard, it is interesting to note that works by ten of the top twenty-seven prizewinners of the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair—Zeng Fanzhi, Zhang Xiaogang, Zhou Chunya, Wang Guangyi, Ye Yongqing, Leng Jun, Mo Yan, Mao Xuhui, Shu Qun, and Guan Ce—regularly go for top prices in today’s international auction market.18Ibid. See the appendix entitled “Top Contemporary Artists (2013/2014),” unpaginated. Of the one hundred top-performing contemporary artists (by auction turnover), forty-seven were Chinese, with Zeng Fanzhi ranking number four, Zhang Xiaogang number ten, Zhou Chunya number twelve, and Wang Guangyi number eighty-four. Other Guangzhou Biennial award-winning artists have also performed well, with Ye Yongping at number 107, Leng Jun at number 157, Mo Yan number 230, Mao Xuhui number 341, Shu Qun number 391, and Guan Ce number 441. And further, although it did not forestall the threat of moving Chinese contemporary art offshore and into the hands of foreign buyers, the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair did give tangible shape to the desire among many artists and art practitioners to establish an independent and domestic art infrastructure based on local scholarship, local critical discourse, and local patronage, a project that continues today to be a complicated but important work in process.

- 1See May 11, 1992, preface to the catalogue for the Guangzhou Biennial Art Fair, unpaginated. The catalogue’s Chinese title is Zhongguo Guangzhou shoujie jiushi niandai: yishu shuangnianzhan youhua bufen zuopin wenxian. Please note that the term “Art Fair” does not appear in the Chinese title of this catalogue, only in the original English title, which is The First 1990s’ [sic] Biennial Art Fair Guangzhou, China, Oil Painting Section, Documentary Works. For the purpose of this essay, the authors have standardized the English title of the exhibition.

- 2Critics involved in the selection of the work included Zhu Bin, Shao Hong, Yi Ying, Yuan Shanchun, Pi Daojian, Peng De, Yang Li, Huang Zhuan, and Yin Shuangxi. See Lü Peng, Zhongguo dangdai yishushi, 1990–1999 [A history of modern Chinese art: 1990–1999], 127.

- 3See “Guangzhou shoujie jiushi niandai yishu shuangnianzhan youhua bufen huojiang zuopin fenggao” [Announcement of the award-winning artwork of the First 1990s’ Guangzhou Biennial, Oil Painting Section], Yishu shichang [Art and market], no. 6 (1992): 67. Also see World Bank GPD per capita statistics, accessed February 28, 2015, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.CD?page=4

- 4See Lü Peng, interview by author, Chengdu, October 16, 2006. Also see numerous primary documents in the Lü Peng Archive at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong, including the invitation card, exhibition application, sponsorship documents, contracts, jury statements, press material, and photographs.

- 5That Deng Xiaoping, preeminent leader of the People’s Republic of China from the 1970s to the 1990s, said “To get rich is glorious” has never been confirmed. But the phrase has frequently been used in the press and particularly among Western writers to describe the ethos of entrepreurship that was encouraged by the Chinese state and developed in the wake of a series of economic reforms that began in the late 1970s and accelerated through the 1980s and 1990s.

- 6With start-up funds provided by entrepreneur Luo Haiquan, the Xishu Art Company was established to fund the operations of the Guangzhou Biennial. However, when expenses exceeded the overly optimistic revenue projections, the Xishu Art Company was unable to meet its obligations, resulting in a lawsuit. See page 248, Jane DeBevoise, Between State and Market: Chinese Contemporary Art in the Post-Mao Era, and documents in the Lü Peng Archive at Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong.

- 7See Wang Lin, Zhongguo: Bajiuhou yishu [China: Post-’89 art]. (Hong Kong: Yishu chaoliu zazhishe,1997): 92.

- 8See “Sun Ping gupiao youxian gongsi zai Guangzhou faxing gupiao” [Sun Ping Company issues shares in Guangzhou], Guangdong meisujia [Guangdong artists], no. 2 (1993): 49.

- 9See Wang Lin, Zhongugo: Bajiuhou yishu [China: Post-’89 art]. (Hong Kong: Yishu chaoliu zazhishe,1997): 92–93.

- 10Yi Ying, “Chao weiping feng zhaqi,” [The wind picks up when the tide is still in]. Beijing qingnianbao [Beijing youth daily], October 15, 1992, 4–5. Also see Geremie Barmé, “Artful Marketing”, In the Red: On Contemporary Chinese Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999): 218.

- 11See Lü Peng “Biaozhun bixu you Zhongguoren ziji lai que ding” [Standards should be established by Chinese people themselves], Yishu shichang, no. 7 (1992): 18–19.

- 12See Ye Yongqing “Zhiyou Zhongguo ren caineng zujin Zhongguo yishu shichang de jianli: Yishujia Ye Yongqing 1991 nian 9 yue 12 ri gei Lü Peng de xin” [Only Chinese people can establish a Chinese art market: A letter to Lü Peng from Ye Yongqing dated September 12, 1991], Yishu shichang, no. 2 (1991): 3.

- 13See Jiang Feng, “Guanyu Zhongguohua wenti de yifeng xin” [A letter about the problem of Chinese painting], Meishu [Art], no. 12 (1979): 10–11.

- 14Zhang Qing, “Beyond Left and Right: Transformation of the Shanghai Biennale, ” Shanghai Biennale 2000, unpaginated.

- 15Zhang Qing, “Beyond Left and Right: Transformation of the Shanghai Biennale,” Shanghai Biennale 2000, unpaginated.

- 16Zhang Qing, “Beyond Left and Right: Transformation of the Shanghai Biennale,” Shanghai Biennale 2000, unpaginated.

- 17If the price of art at auction can be used as a yardstick, in at least one study, sales in China of contemporary art at auction surpassed the U.S. art market, totaling 601 million euros in 2014, versus 552 million euros in the U.S. See Contemporary Art Market 2014: The Artprice Annual Report, 21, accessed February 28, 2015, http://imgpublic.artprice.com/pdf/artprice-contemporary-2013-2014-en.pdf

- 18Ibid. See the appendix entitled “Top Contemporary Artists (2013/2014),” unpaginated. Of the one hundred top-performing contemporary artists (by auction turnover), forty-seven were Chinese, with Zeng Fanzhi ranking number four, Zhang Xiaogang number ten, Zhou Chunya number twelve, and Wang Guangyi number eighty-four. Other Guangzhou Biennial award-winning artists have also performed well, with Ye Yongping at number 107, Leng Jun at number 157, Mo Yan number 230, Mao Xuhui number 341, Shu Qun number 391, and Guan Ce number 441.