This text was originally published under the theme “Polish Radio Experimental Studio: A Close Look”. The theme was developed in partnership with Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź (MSŁ). It was edited by Magdalena Moskalewicz, MoMA with Daniel Muzyczuk, MSŁ. The original content items in this theme can be found here.

Depending on the type of recording, the whole apparatus changes like a chameleon, and the composer, changing the “qualities” of the wall, acts a bit like a sculptor and a bit like a painter. This whole system could be easily described as optical music recording . . .

—Oskar Hansen

Open Form Music

In 1966 Oskar Hansen, who had recently redesigned the working environment of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio (PRES), went to Stockholm to participate in the Fylkingen congress, an annual meeting of experimental composers. Gathered in the National Museum of Science and Technology under the banner Visioner av Nuet (Visions of the Present), the congress set out to explore new relationships between music, art, and science. Many leading figures in the budding field of intermedia art— creative practices that crossed the boundaries of different art forms, often employing new technologies—participated: Korean-American artist Nam June Paik showed one of his robots playing audiotaped speeches, and American composer Alvin Lucier attempted to control brainwave signals to create sounds in a rendition of his extraordinary Music for Solo Performer (1965). Yet it was a musical composition by Iannis Xenakis that drew Hansen’s attention:

The piece, a background of musical events of the same pitch but of a changing, fluently modulated intensity, caused even the smallest sounds of different pitches to be heard very clearly (a candy wrapper being unfolded, a cough, a chair creaking). A background “crawling” on the floor, climbing on the walls and the ceiling, as if looking for events to reveal, only to disappear through the window like sonic fog. A clearly visual piece—a monochromatic continuity characterized by formal insufficiency—awaiting events.1Oskar Hansen, notes from the Fylkingen congress cited in Oskar Hansen, Towards Open Form / Ku Formie Otwartej (Warsaw: Foksal Gallery Foundation, Revolver, Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts Museum, 2005), p. 221. Translation Marcin Wawrzyńczak and Warren Niesłuchowski.

At the time, Xenakis, a Greek composer who had trained as an architect and worked with Le Corbusier on the much-lauded Phillips Pavilion featuring the Poème Electronique multimedia presentation at the Brussels Expo in 1958, was developing his ideas of polytopes, installations featuring sound, light, and architecture. Exploring what he called stéréophonie cinématique, Xenakis presented his Fylkingen audience with the sensation of mobile sound. This was, Hansen declared in his personal notes, “an important experience—Open Form music.”

Open Form (Forma Otwarta) was Hansen’s own concept, which he had announced to the world in a 1959 essay.2Oskar Hansen, “Forma Otwarta” in Przegląd Kulturalny no. 5, (1959), p. 5. Author’s translation. In this short manifesto, he argued for spatial forms that were incomplete and, as such, required the creativity or participation of their users. Architectural space, according to Hansen, should be considered in terms of change and movement, chiefly in terms of its potential to be reorganized by those who occupy it. By engaging audiences/users in these alterations, Open Form had the potential to remind humankind of its embodied beings. They would also make the individual more attuned to the ordinary: “As Dadaism in painting broke the barrier of traditional aesthetics, so the Open Form in architecture will also bring us closer to the ‘ordinary, mundane, things found, broken, accidental’”.3Oskar Hansen in Oscar Newman, Ciam ’59 in Otterlo. Documents of Modern Architecture, no.1 (Hilversum: G van Sanne, 1961), p. 191. Hansen’s concept originated in his reflections on architecture, but his theory laid claim to all spheres of culture, including music.

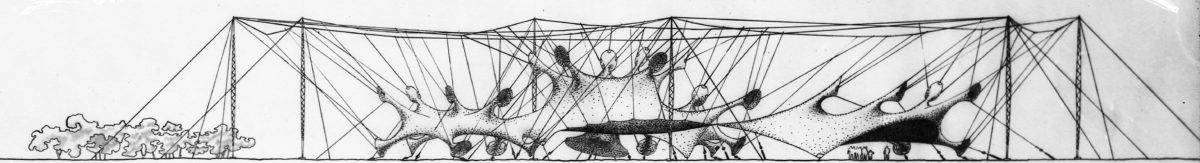

One of Hansen’s earliest schemes exploring the potential of this concept was created with Józef Patkowski, who founded the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio in 1958. That same year, Hansen designed the My Place, My Music (Moje Miejsce, Moja Muzyka) pavilion for the Warsaw Autumn festival, the most important international forum for experimental composers in Eastern Europe during the period of communist rule. Working with Patkowski, Hansen experimented with the spatiality of music, creating what he called an “audiovisual space-time.” The pavilion was to be a large fabric structure, like a shirt with many sleeves, suspended in a park close to the banks of the Vistula River. Each arm of the pavilion was to have a speaker at its end. Viewers were to be encouraged to move through the space, listening to the music with a heightened awareness of the natural setting beyond.

In 1965 Hansen described his thinking for this unbuilt pavilion in terms that echoed Xenakis’s concept of polytopes: “In concert halls I have always been unpleasantly aware of the highly stringent division into orchestra and audience space, accentuated by the footlights and other dividing elements. I wished to accentuate the feeling of space that music arouses and make room for individual ways of reception.” Moving by and between the speakers, Hansen continued, “People . . . would have the music at the back and in front, and in front it would flow from all sides. In effect, every member of the audience would hear the music in all its varied tones; he would, in a way, have it all to himself. We would have attained, then, something that could be described as ‘time and space’ qualities in music.”4Oskar Hansen interviewed by Stanisław K. Stopczyk, Projekt, no. 1 (1965), pp. 8–10.

Hansen’s Open Form theory was ineluctably a product of its age. Like many Polish intellectuals who had experienced Stalinism’s conscription of the arts as propaganda for the collective society, Hansen was committed to the idea of the freedom of the individual—for both artists and audiences. When during the late 1950s Poland underwent the turbulent period of de-Stalinization known as the Thaw, abstraction, Surrealism, experimentation, and other modernist preoccupations were taken as signs of resistance to the instrumental uses of art by power. With its emphasis on the active roles of audiences in the creation of an artwork or the occupation of spaces, Hansen’s theory was a classic product of the Thaw. In stressing the need for active, engaged individuals shaping their world, his Open Form theory chimed with the calls for freedom of speech and thought as well as the rejection of central command that sounded across the Eastern Bloc in 1956. The theory was also highly compatible with new ideas emerging abroad in modern architecture and new music, as well as with the impending international wave of happenings, performances, installations, and other artistic environments.5Hansen presented his ideas at international meetings of young architects known as Team X, an offshoot of CIAM (Congrès international d’architecture moderne), who sought to reconcile their commitment to modernism with existential humanism. Openness was a much-valorized theme. Umberto Eco, for instance, began his highly influential and widely translated 1962 book The Open Work (Opera Operta) with a discussion of the freedom of interpretation given to performers by Karlheinz Stockhausen’s scores.6Umberto Eco, The Open Work (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 1. And John Cage, one of the most influential figures in the development of experimental music, was then championing the idea that any sound could be used in music. In his celebrated composition 4’33” (1952), the performers were instructed to rest for the duration of the piece, thus creating the awareness that there need not even be an intention to make music for there to be music. All that was required was openness to aural phenomena. To make his point, he credited architecture and sculpture with possessing an openness to the environment that musicians and composers had been taught to eschew:

The glass houses of Mies van der Rohe reflect their environment, presenting to the eye images of clouds, trees, or grass, according to the situation. And while looking at the constructions in wire of the sculptor Richard Lippold, it is inevitable that one will see other things, and people, too, if they happen to be there at the same time, through the network of wires. There is no such thing as an empty space or an empty time.7John Cage, “Experimental Music” (originally a talk given at the convention of the Music Teachers National Association in Chicago in 1957) in Silence. Lectures and Writings (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2010), p. 8.

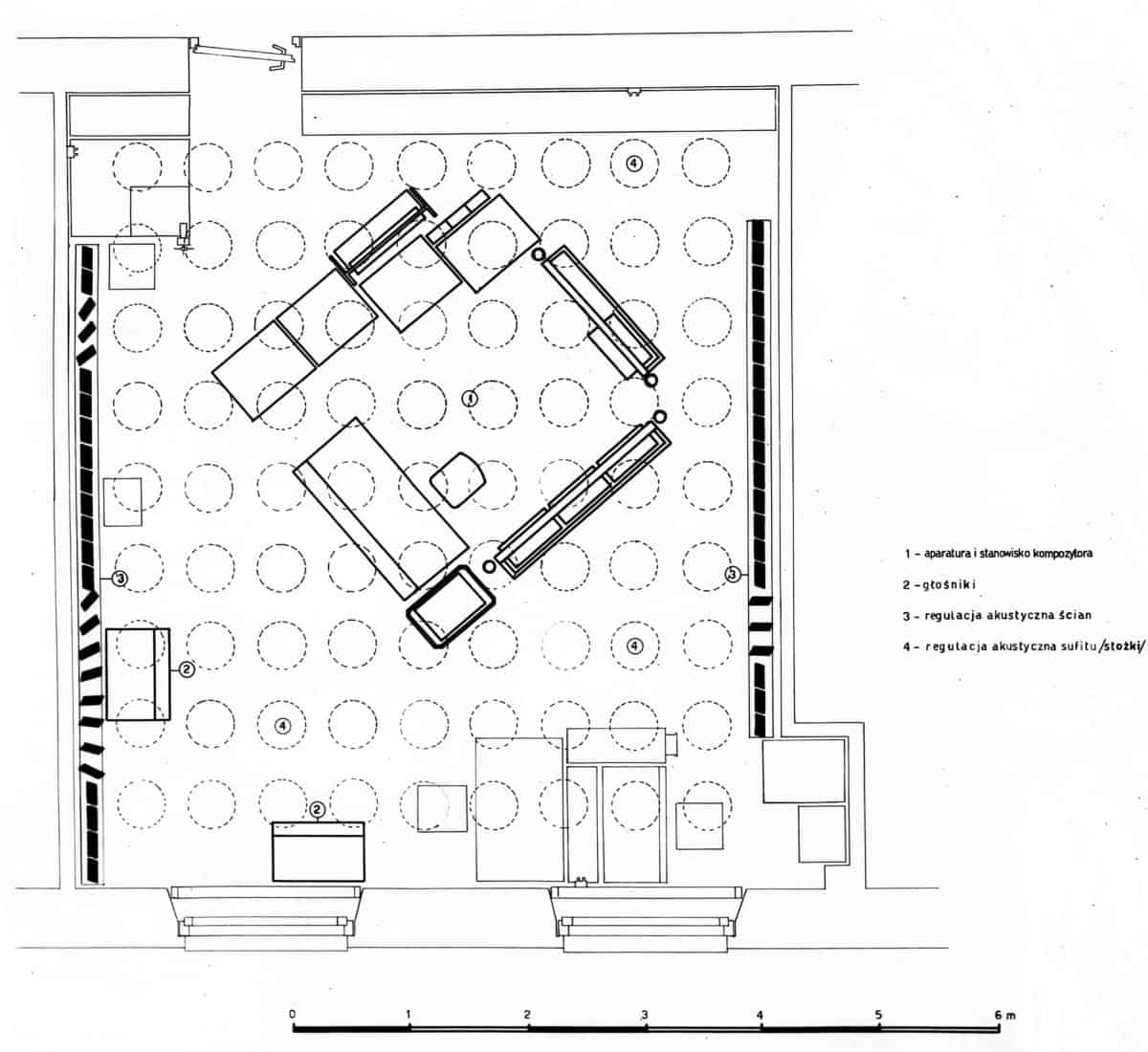

Opening the Experimental Studio

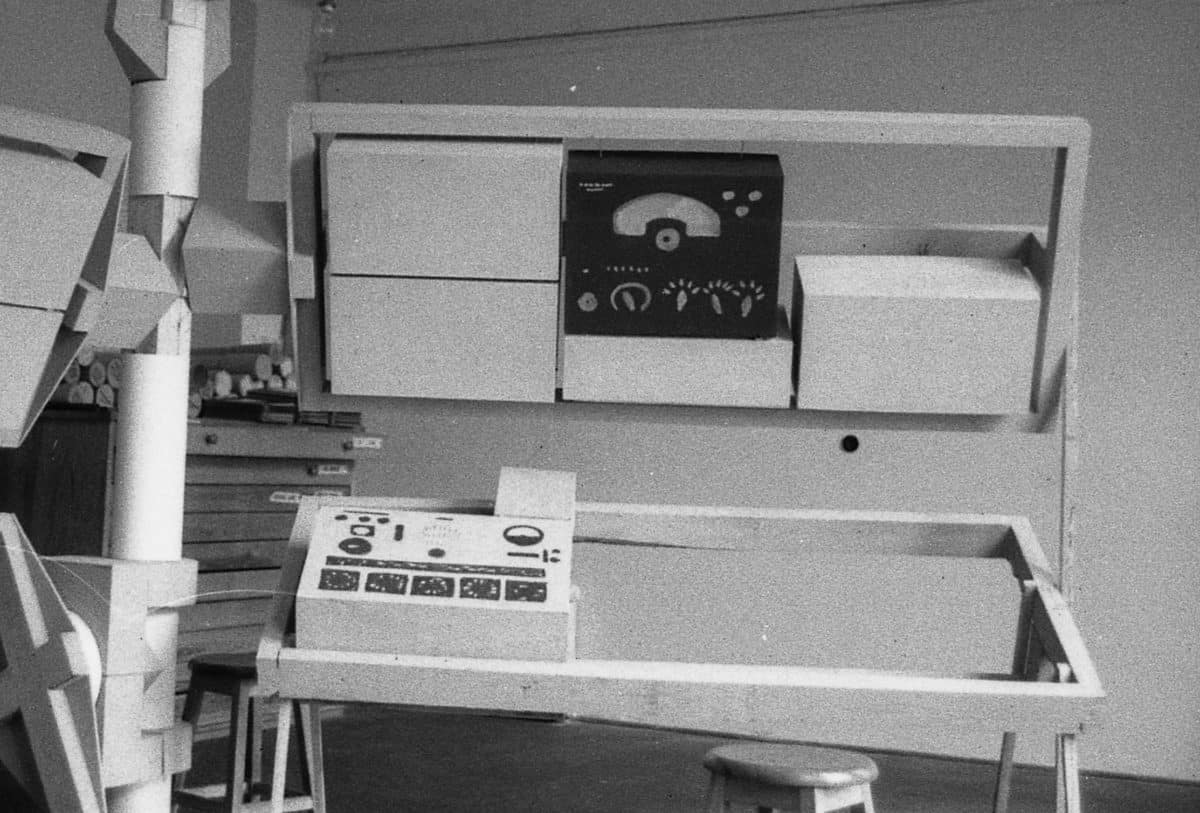

The My Space, My Music pavilion was never constructed, but this was not the end of Hansen’s interest in Open Form music. In the early 1960s Patkowski secured the resources to improve the Experimental Studio at Polish Radio. Making visits to Milan, Paris, and Cologne, he surveyed the operations of new experimental studios. In addition to the generators and filters that had been created by the Warsaw Studio’s engineers, Patkowski acquired an Elektro-Mess-Technik stereo console and Telefunken reel-to-reel magnetic tape recorders from West Germany.8Włodzimierz Kotoński, Muzyka Elektroniczna (Kraków: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 2002), p. 40. His ambition was not simply to reproduce the facilities found elsewhere in Western Europe. He imagined the new studio as a kind of laboratory where a composer, working closely with a skilled engineer, could manipulate sounds materially (by editing and joining tape) and electronically (using filters and generators). Judgments could be made about the timbre, dynamics, and pitch of any sound with little or no need to involve musicians. The landmark works produced by the Studio in its first years were Włodzimierz Kotoński’s Etude for One Cymbal Stroke (Etiuda na jedno uderzenie w talerz, 1959) and Krzysztof Penderecki’s Psalmus (1961), widely regarded as a pioneering work of electronic music. Using recordings of simple musical elements (in the case of Psalmus, vowels and consonants delivered by two human voices), both composers and engineer Eugeniusz Rudnik processed these sounds over many days to create rich sonic compositions.

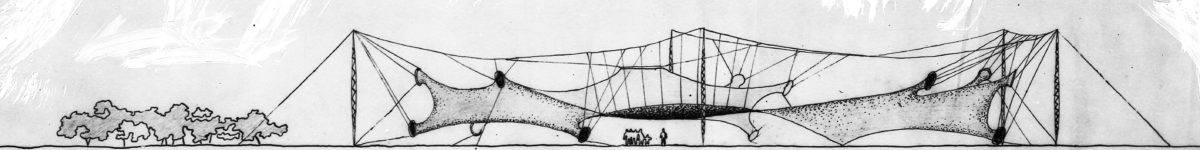

Patkowski turned to Oskar and Zofia Hansen in 1962 to design the new studio in a six-by-six-meter room at the Polish Radio headquarters. In turn, the Hansens called on the expertise of acoustician Witold Straszewicz. Their design took flexibility and “changefulness” as its chief principles. The composer, usually working with the engineer in a central hub, could move much of the equipment suspended from a horizontally revolving axle above. The walls were screened with movable panels and curtains so that the composer could change the acoustic qualities of the studio itself. The architects conceived of the activities of the composer as akin to that of sculpting sound. Hansen outlined his design to a journalist in 1965:

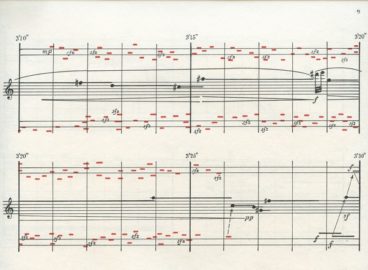

The panels differ in shades, from white to black with only two more lively colors: red and yellow. By revolving the panels we attain proportional changes in their acoustical sensitivity and also in their plastic effects, that is, in the visual qualities of this section of the wall: the angle at which the panel is set determines the contrast between the panel and its background. And so, depending on the type of recording, the whole apparatus changes like a chameleon, and the composer, changing the “qualities” of the wall, acts a bit like a sculptor and a bit like a painter. This whole system could be easily described as optical music recording and should render assistance to a composer of electronic music who, after a day’s work, wishes to note the exact acoustical conditions of the studio in which he has been making the music.9Oskar Hansen interviewed by Stanisław K. Stopczyk, Projekt, no. 1 (1965), pp. 8–10.

By according color a role in this laboratory of sound, Hansen formed a link to the long historical chain of modernist experiments with light and music that could be traced back to Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin before World War I. Moreover, this was a shared enthusiasm in Poland in the early 1960s, when a number of the composers who worked with the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio made a serious engagement with the visual arts. Both Zygmunt Krauze and Bogusław Schaeffer made compositions inspired by the Unist theories formulated in the 1930s by the Polish Constructivist artist Władysław Strzemiński.10Krauze’s Five Unist Compositions (Pięć kompozycji unistycznych, 1963) and Schaeffer’s Hommage à Strzemiński (recorded in the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio in 1967). And Penderecki used painting as a scale for his music. Speaking in 1960, the year before he began working with the Studio, he said:

I am looking for deeper interconnections between painting and music. . . . For me the most important issue is the problem of solving colors, color concentration, as well as operating the texture and time. There are, for instance, paintings in which through multifariousness, we achieve an impression of space and time. The task of music is to transplant all these elements of time and space, color and texture onto music.11Jerzy Hordyński, “Kompozytorzy współcześni. Krzysztof Penderecki” in Życie Literackie, 44 (1960), pp. 4, 8, cited by Danuta Mirka, The Sonoristic Structuralism of Krzysztof Penderecki (Katowice: Akademia Muzyczna, 1997), p329.

The day-to-day operations of the new studio were not as successful as the Hansens and their patron Patkowski had hoped. Very few composers used the studio to create and record live electronic works, an emergent form of musical creativity that was being developed elsewhere and, according to the Hansens’ design, should have ensued from the capacity to modify and manipulate the acoustic conditions of the studio. In fact, the space was too small and too full (the facility lacked adequate storage room for its equipment). Engineer Rudnik recalled the oppressive heat generated by the equipment: “If I worked for twenty-five hours without a break in this little room, where the tubes were radiating heat, and it was the middle of the summer or a June night, I had to open the windows. Eighty meters below, cars were driving by on Malczewski Street, and so I could either listen to electronic music or to the rumble of a tractor.”12“How much Rudnik is in Penderecki, and how much Rudnik is in Nordheim? Interview with Eugeniusz Rudnik” Warsaw available at post.moma.org starting January 28. The windows of the Open Form studio remained closed. The framework designed by the Hansens to hold the studio’s electronic apparatus also presented problems. When later on, new and often more compact pieces of equipment were acquired, it proved to be unnecessarily large. Paradoxically, over the years, the studio came to illustrate Hansen’s antonymous concept of the closed form, namely a structure that could not accommodate change.

After the redesign of the Experimental Studio, Hansen’s career took him away from the world of music.13Later in his career, Hansen created one important Open Form performance space in Warsaw when he was commissioned in 1972—with Piotr Damięcki, Henryk Górka, Stanisław Górski, Adolf Szczepiński, and Włodzimierz Witkowski—to renovate the Studio theater in the Palace of Culture. See Oskar Hansen, “To Break Down the Barriers between the Audience and the Actor” in Poland, 10 (1975), p. 38. Nevertheless, as a professor at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art, he taught artists and architects who shared his vision of the free potential of open works. In September 1966 the Foksal Gallery in Warsaw, the key venue for the neo-avant-garde in Poland, hosted an “audio-visual séance” created by artists Grzegorz Kowalski (who had recently been one of Hansen’s students), Henryk Morel, Cezary Szubartowski, and composer Zygmunt Krauze. After entering the gallery through a narrow slit and along a bright canvas “sleeve,” the public—in groups of ten—found themselves in the darkened and indefinite interior. Underfoot, the floor was covered with a bed of broken glass on sheet metal, while the space itself was filled with metal objects, including massive springs, bent panels, and broken barrels, which had been gathered from a scrapyard. The final space before the exit was filled with nets that slowed down the exit of the visitor from the gallery. Like Hansen’s sculptural conception of the Experimental Studio at Polish Radio, the environment combined visual and acoustic effects. A leaflet published by the gallery described the thinking behind the dramatic lighting effects: “The authors’ intervention in the visual sphere was to create variable lighting situations as well as to consciously use darkness; for instance, short bursts of light interrupting long periods of complete darkness revealed the show’s different stages, exposing the participants’ anonymous and unrestrained actions. Longer stretches of full lighting, revealing the whole installation, exposed the mystery of the sound-filled darkness.”145x Galeria Foksal—PSP (Warsaw, 1966), n.p. Author’s translation.

Entitled 5x, the installation was the setting for five happenings organized over five consecutive evenings. The first night featured a forty-five-minute performance by British musicians Cornelius Cardew, David Bedford, and John Tilbury of a La Monte Young composition featuring long sustained tones. The key role was not given to these British musicians who were in the city for the Warsaw Autumn festival. Each “séance” depended on the interaction of the visitor with various instruments, including a contact microphone, a transistor radio, and an amplified music box, that were introduced on different nights, and with the objects and lights in the space. To make this clear, the invitation carried the words “this entrance card authorizes participation and co-creation.” The organizers of the event wrote:

From start to end, each séance was different for each participant. The start was the moment of entry, when the installation was set in motion, and the moment of departure depended on the decision of the individual. Irregular exchanges between participants took place throughout the séance. Their actions caused situations of variable intensities.155x Galeria Foksal—PSP (Warsaw, 1966), n.p. Author’s translation.

This emphasis on the agency of the individual was not simply a compositional technique for the generation of new art. Indebted to Hansen’s Open Form theory, 5x was the expression of a philosophy that rejected the determining role of the expert or the authority.

Freedom in Doubt

5x and other Open Form musical experiments created in Warsaw in the 1960s presented an optimistic view of the individual.16The Spatial-Musical Composition (Kompozycja przestrzenno-muzyczna) created by Krauze and Morel with architect Teresa Kelm in Galeria Współczesna, Warsaw, in 1968, was another key installation that required the participation of its audience. See David Crowley and Daniel Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric. Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957–1985 (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2012), pp. 146–52. By encouraging listeners to become performers and shape their own experiences of the musical performance as an event, the agency of the individual, it was claimed, was accentuated. Nevertheless, such performances offered a largely uncritical perspective on the meanings that might be attached to sound, the movement of the body, and, equally important, the technologies on which experimental sound-making and recording relied. At the end of the 1960s, however, new attitudes emerged in Polish culture that put the existential humanist precepts of Thaw culture under pressure. A growing interest in cybernetics and communication theory drew attention to the central control of the media by the communist state. At the same time, the interest of Conceptual artists in the performativity of language meant that, in the 1970s, the shibboleths of Polish intellectual life—not least freedom—came to seem like problems rather than solutions.17For discussion of Polish art in the 1970s, see Luiza Nader, Konceptualizm W PRL (Warsaw: Foksal Gallery Foundation, University of Warsaw Press, 2009); Piotr Piotrowski, Dekada. O syndromie lat siedemdziesiątych, kulturze artystycznej, krytyce, sztuce—wybiórczo i subiektywnie (Poznań: Obserwator, 1991); Łukasz Ronduda, Polish Art of the 1970s (Jelenia Góra: Polski Western; Warsaw: Centre for Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle, 2009).

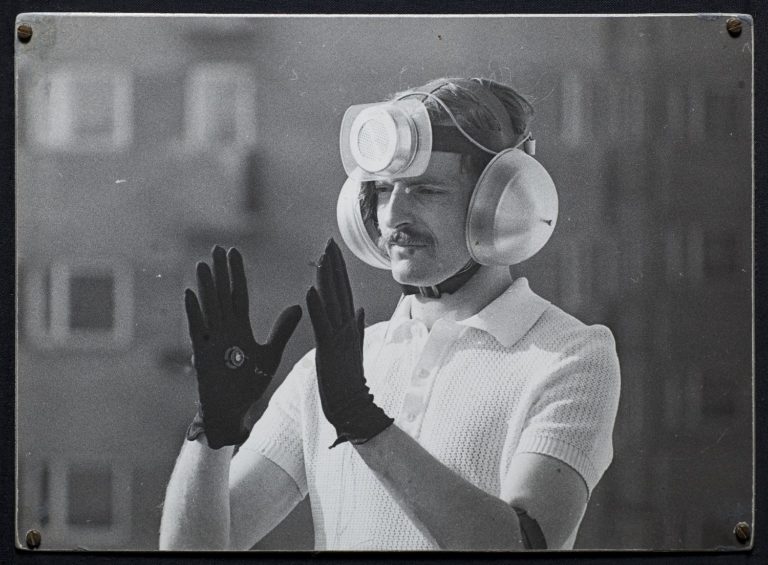

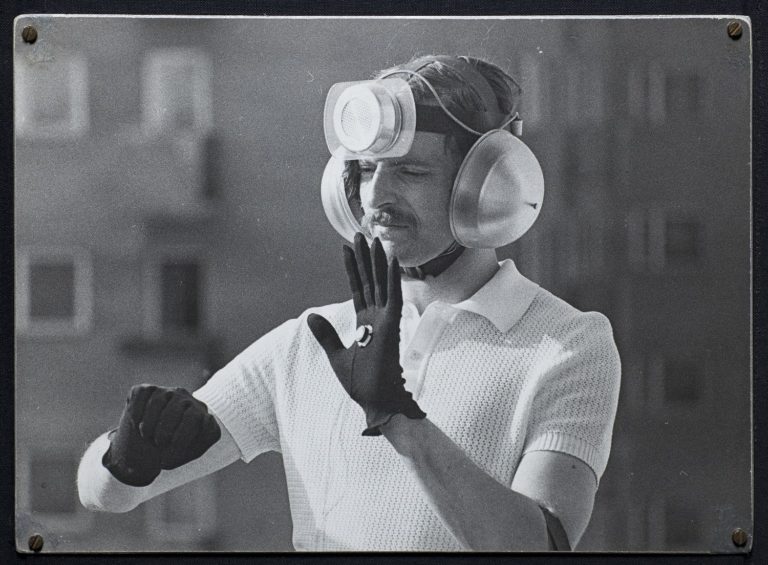

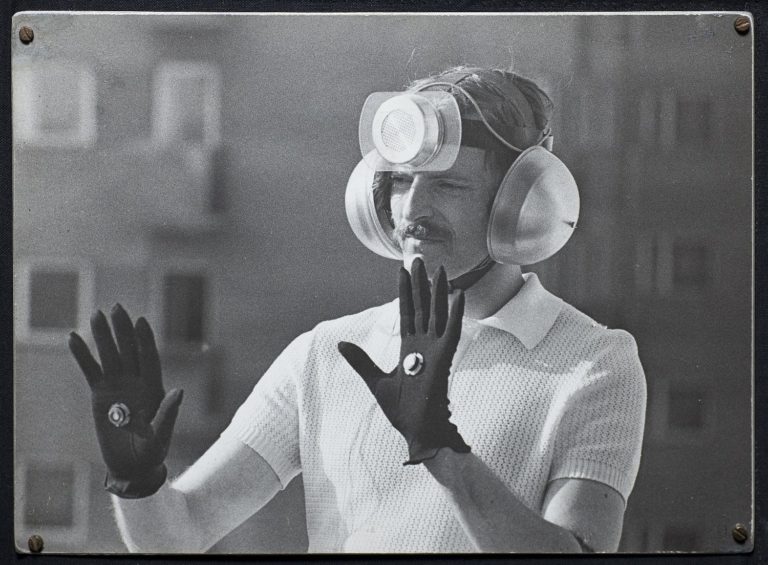

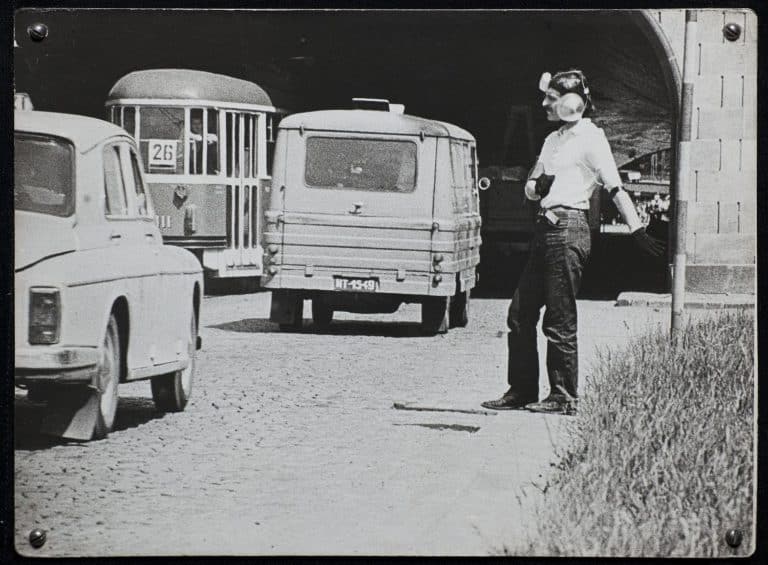

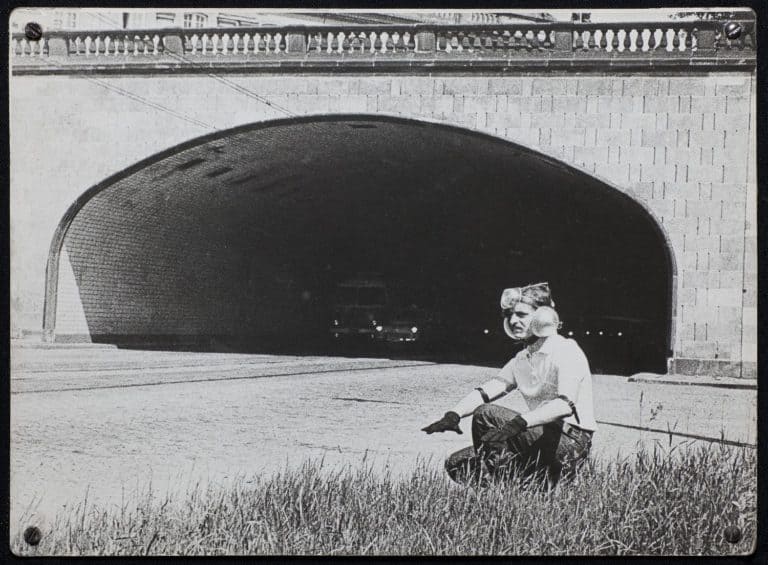

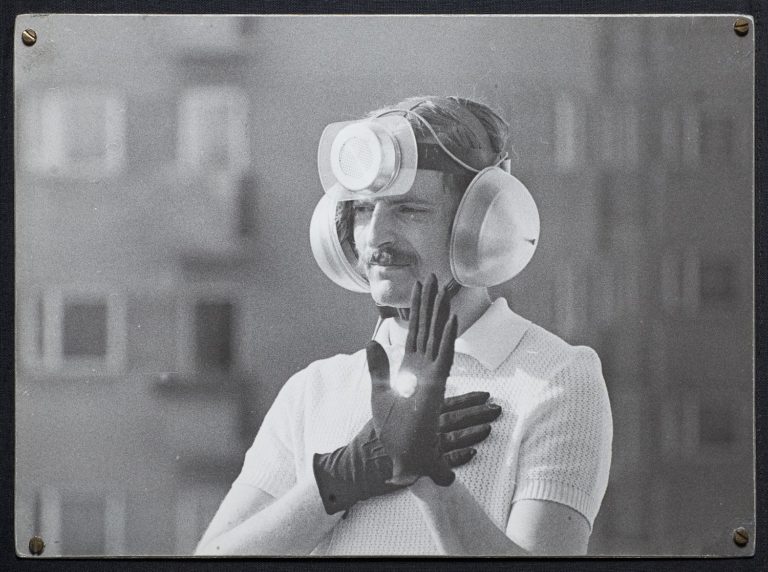

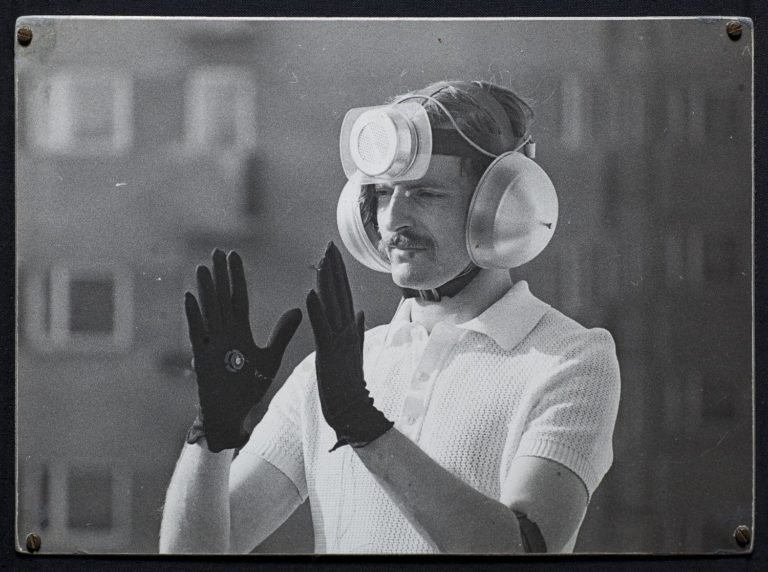

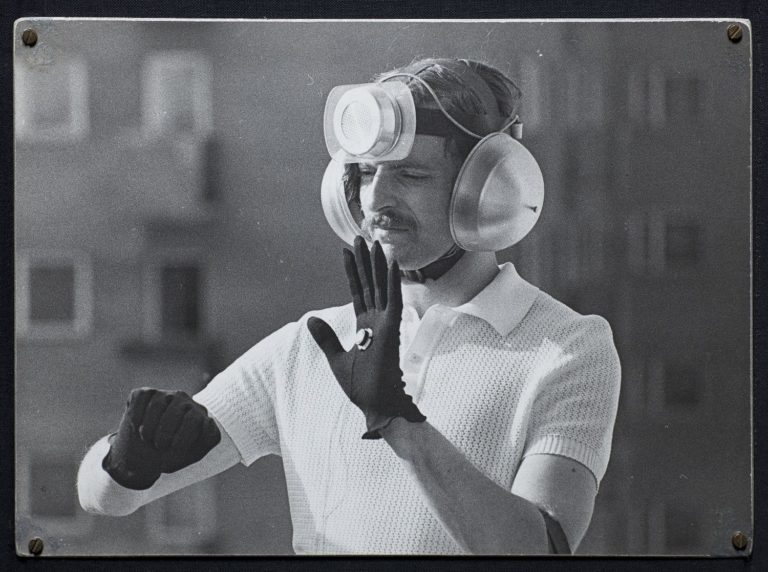

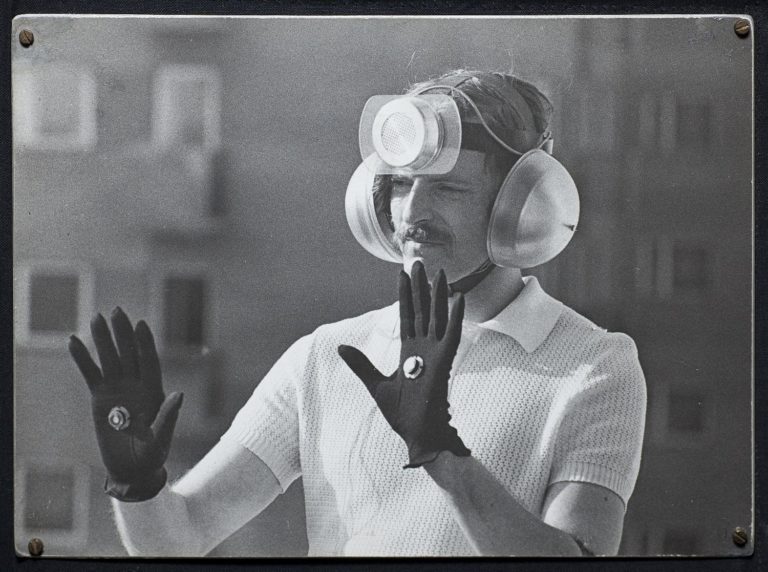

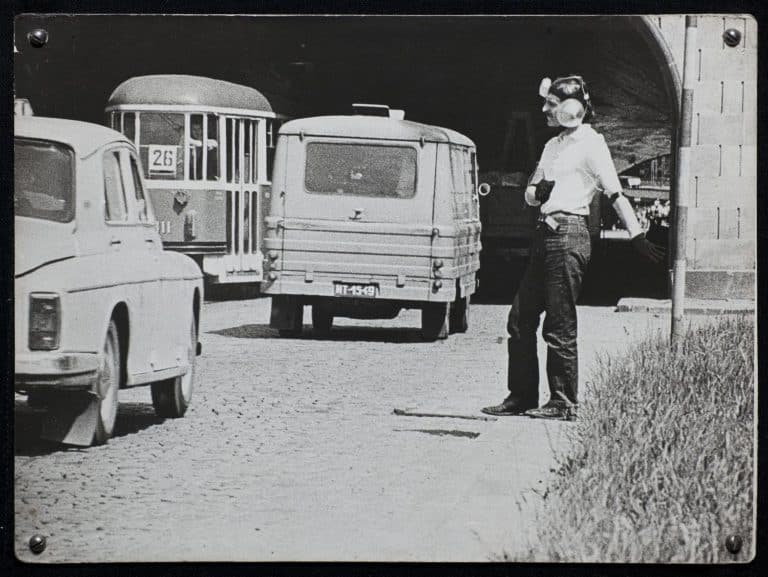

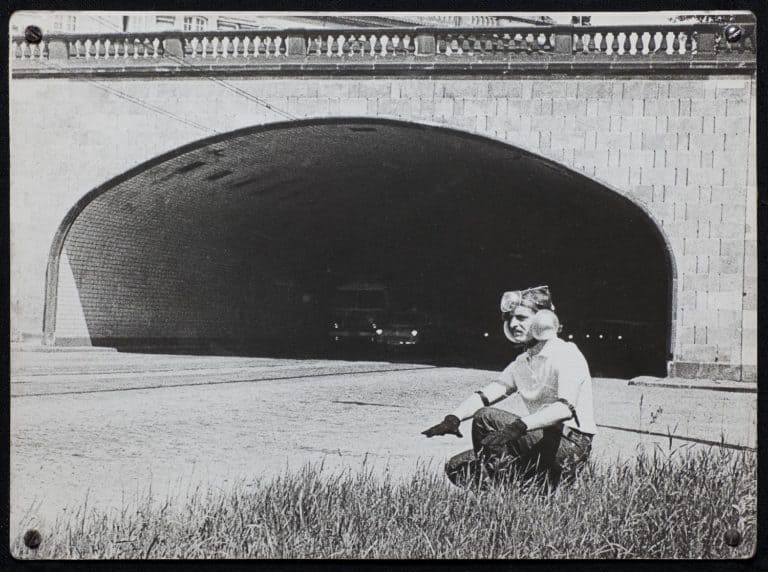

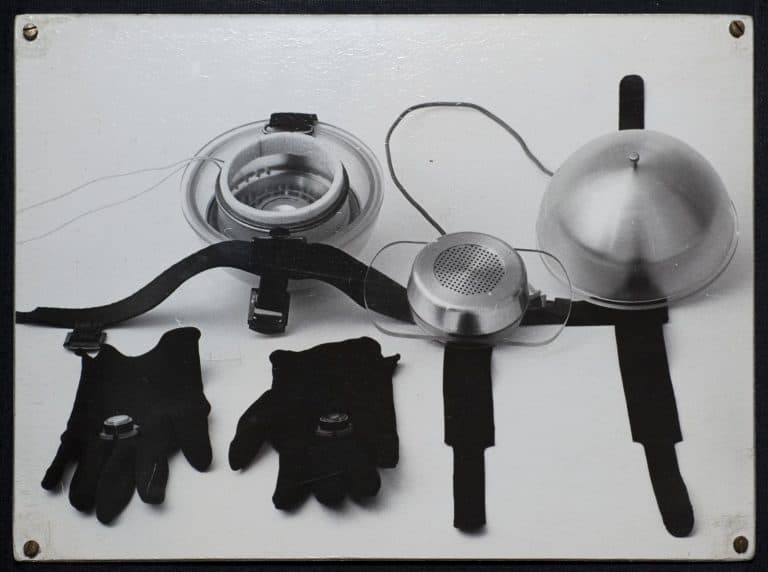

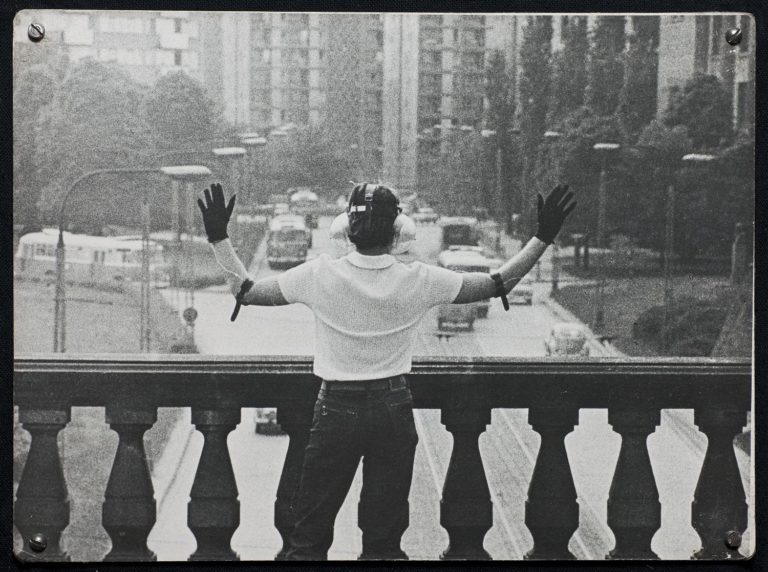

In the late 1960s the young artist Krzysztof Wodiczko, a graduate of the Warsaw Academy of Fine Art industrial design program, was working as a designer for Unitra, the main state electronics conglomerate in Warsaw. The son of a prominent conductor, he was also closely connected to the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio. In fact, he turned to the Studio’s engineers for advice on the construction of a series of technological artworks that can be understood as musical instruments.18Interview with Krzysztof Szlifirski by the author, Warsaw, 2010. His Personal Instrument (Instrument Osobisty) of 1969 was, for instance, an electronic device worn on the head and hands. Responding to the movements of the wearer, the device allowed the individual to amplify or diminish the flow of sound from the environment. A sensor on the glove turned the hand into a microphone. With his or her arms raised to filter the sounds, the wearer seemed to be conducting the city, making the traffic and conversations and footsteps of the passersby seem like instruments in a great urban orchestra. In a text describing the operation of the Personal Instrument, Wodiczko wrote:

The instrument allows the conversion of ambient sound.

The instrument relies on the movement of the hand.

The instrument responds to sunlight.

The instrument is portable.The instrument is used in any place and at any time.

The instrument is intended solely for the author.

The instrument enables the author to achieve virtuosity.19Krzysztof Wodiczko: Pojazd / Vehicle (Warsaw: Foksal Gallery, 1973).

Product (Produkt), created by Wodiczko and composer Szábolcs Esztényi for a group exhibition at the Galeria 10 KMPiK Ruch in Warsaw the following year, centered on an altered Moskva refrigerator.20This discussion of Product and Instrument–Percussion Laboratory is indebted to Łukasz Ronduda, “Krzysztof Wodiczko-Projektowanie I Sztuka,” Piktogram, 7 (2007), pp. 12–27. The ordinary sounds of the fridge in operation were amplified to fill the gallery with a low hum. Occasionally, the artists would modify the cooling units so that the appliance rocked, adding a percussive effect. When the door of the fridge was opened, a nerve-jarring tape recording of a microphone being scraped by Esztényi on different surfaces could be heard. Inside the fridge, a piece of meat decayed under a red spotlight, adding considerably to the sensory effects of the artwork over the course of the exhibition. Instructions from the Moskva’s user’s manual were reprinted in the exhibition catalogue, serving effectively as a kind of event score. When this instrument was “played” by a viewer opening the door, the effect was registered across the senses: sight, sound, touch, and, increasingly, smell.

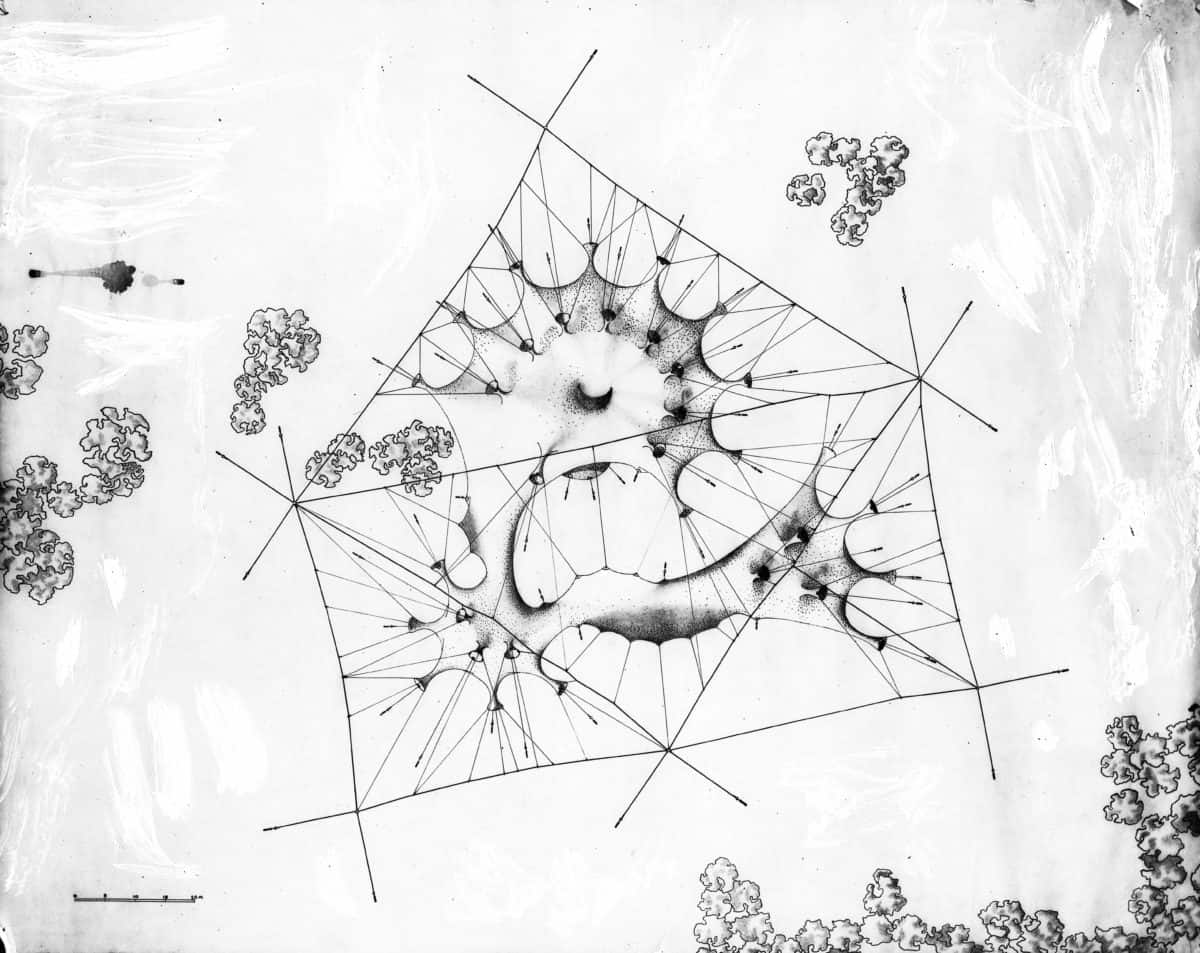

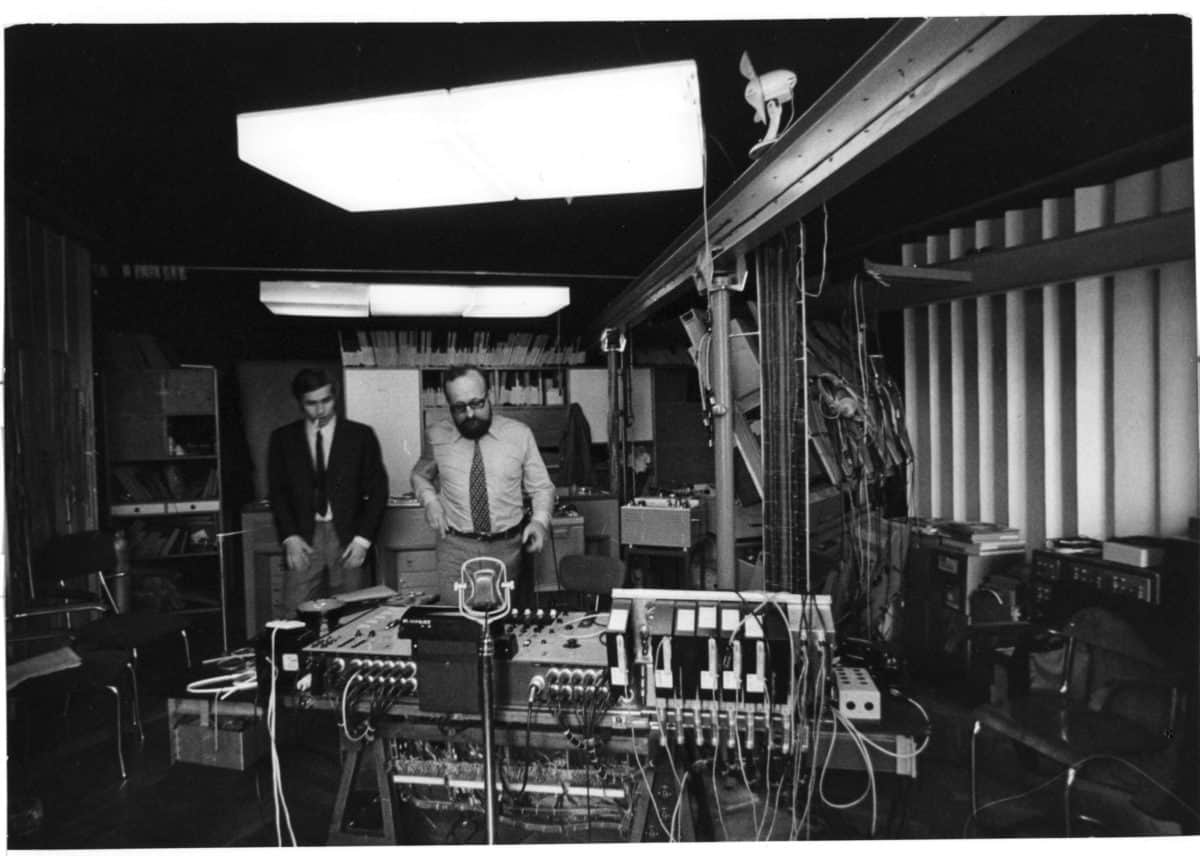

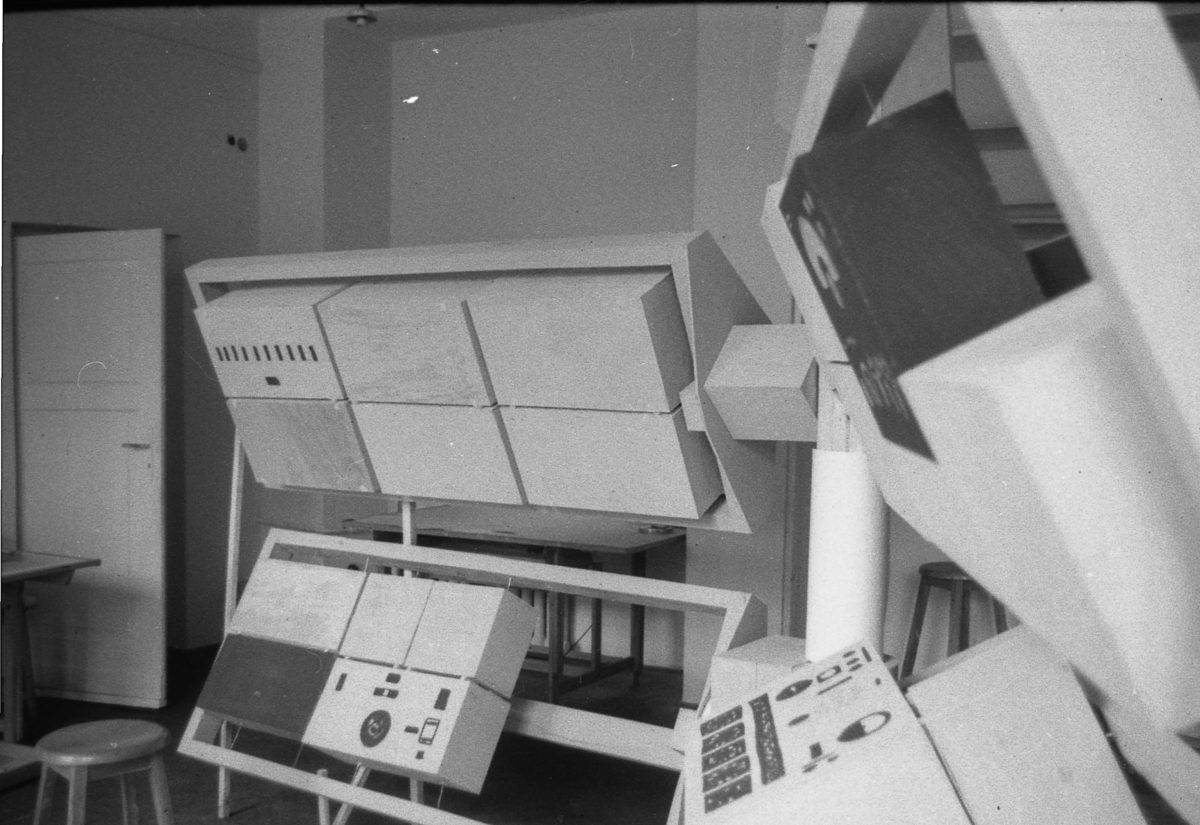

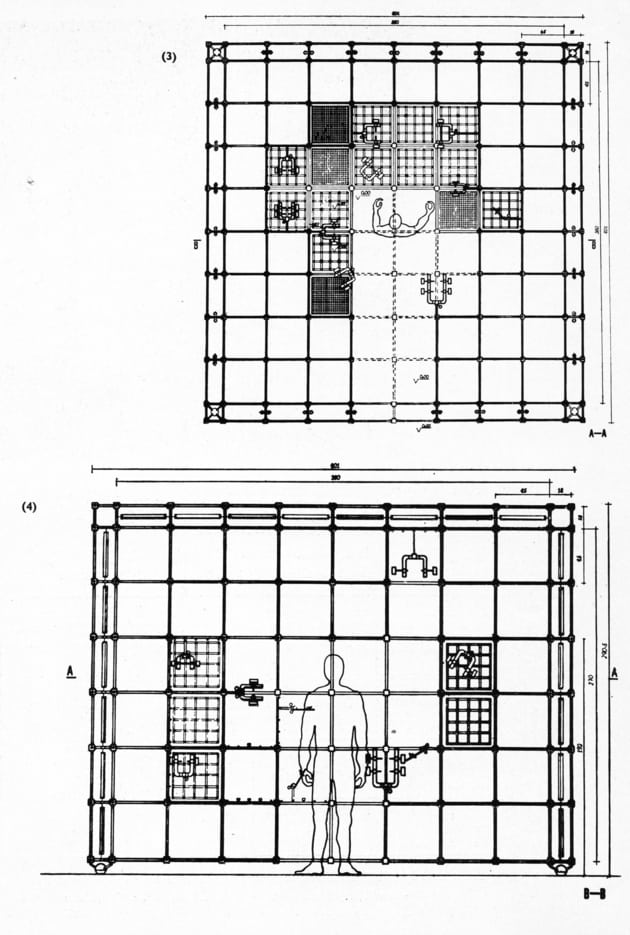

One year later Wodiczko prepared an instrument for the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio. Instrument–Percussion Laboratory (Instrument–laboratorium perkusyjne) was a compact grid of metal beams and joints that formed a frame with precise dimensions (396 x 396 x 288 cm). Panels within the framework could carry flat grilles to hold sound sources (including the percussive instruments of the object’s title), microphones, and lighting equipment. With strong columns at the corners, the structure could be repositioned in different settings. Wodiczko arranged for the structure, which was illuminated by its own lights, to be photographed in darkened space, thereby emphasizing its universal qualities. In the technical drawings of the design, he presented the performer at the heart of the structure as a human silhouette, in the manner of an ergonomic system being employed by industrial designers or even the human figure framed by geometry in Le Corbusier’s Modulor (1945) system for architectural measurement. The Percussion Laboratory was, it seemed, the most flexible and universal of instruments. “In their experiments today,” wrote Wodiczko, with the deadpan logic of the design technocrat, “a great number of composers and performers use percussion-generated audio material. Musicians like this material for its acoustic variety. The simplest percussive sources of sound are forms made with solid, rigid, or acoustically resilient matter, structured as open forms or planes, in the shape of pipes, rods, sheets, foils, the so-called acoustic niches of various sizes, quantities, and proportions. Musicians dream of freely combining, exchanging, congesting, rearranging, and operating such forms to fit their intentions and needs.”21Krzysztof Wodiczko, “Instrument–laboratorium perkusyjne” in Res Facta, 5 (1971), p. 185. My emphasis. Author’s translation.

In these three projects, Wodiczko seemed—at least ostensibly—to share many of the Open Form enthusiasms of the preceding generation. The Personal Instrument turned everyday activities such as walking in the city into music; the Product allowed the viewer to become a performer in the setting of the gallery; and the Instrument–Percussion Laboratory was, as Wodiczko said explicitly, an Open Form. Yet the forms of these objects clearly confounded the neutral, technical explanations that Wodiczko gave his works. They are better understood as allegorical devices. The Personal Instrument, for instance, alluded to the practices and technologies of surveillance, a branch of applied electronics that was put to malign effects in the Eastern Bloc under communist rule. Moreover, Wodiczko’s instrument—which seemed to require the emphatic hand and arm movements of it wearer—produced the unsettling image of a man under the control of a machine. Similarly, the Instrument–Percussion Laboratory contained its user, dreaming of control over his or her environment, in a prisonlike grid of geometry.

The differences between Wodiczko’s Instrument–Percussion Laboratory and Hansen’s design of the Experimental Studio are less a matter of form or design than of attitude and context. Hansen’s ideas emerged in the aftermath of Stalinism and were given form during the first half of the 1960s, a period when the party-state seemed to strike a deal with artists, composers, and other members of the cultural intelligentsia: you can have the freedom to experiment as long as you don’t contest our right to organize the world. This is what dissident Hungarian sociologist Miklós Haraszti was later to call the Velvet Prison.22Miklós Haraszti, The Velvet Prison. Artists Under State Socialism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1989). Wodiczko, by contrast, began his career as an artist and designer in 1968, another turbulent year, which saw violent repression of student protests on the streets of the Polish capital as well as the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces to put down the Prague Spring.23The invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces on the night of 20–21st August 1968 brought about the end of the liberalizing movement in the country. This event shattered the hope held by many Eastern European intellectuals inside and outside Czechoslovakia that Soviet style socialism could be reformed and accelerated the spread of dissent in the region. After these events, the rhetoric of freedom seemed, at least to some intellectuals including Wodiczko, to have a hollow sound.

- 1Oskar Hansen, notes from the Fylkingen congress cited in Oskar Hansen, Towards Open Form / Ku Formie Otwartej (Warsaw: Foksal Gallery Foundation, Revolver, Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts Museum, 2005), p. 221. Translation Marcin Wawrzyńczak and Warren Niesłuchowski.

- 2Oskar Hansen, “Forma Otwarta” in Przegląd Kulturalny no. 5, (1959), p. 5. Author’s translation.

- 3Oskar Hansen in Oscar Newman, Ciam ’59 in Otterlo. Documents of Modern Architecture, no.1 (Hilversum: G van Sanne, 1961), p. 191.

- 4Oskar Hansen interviewed by Stanisław K. Stopczyk, Projekt, no. 1 (1965), pp. 8–10.

- 5Hansen presented his ideas at international meetings of young architects known as Team X, an offshoot of CIAM (Congrès international d’architecture moderne), who sought to reconcile their commitment to modernism with existential humanism.

- 6Umberto Eco, The Open Work (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 1.

- 7John Cage, “Experimental Music” (originally a talk given at the convention of the Music Teachers National Association in Chicago in 1957) in Silence. Lectures and Writings (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2010), p. 8.

- 8Włodzimierz Kotoński, Muzyka Elektroniczna (Kraków: Polskie Wydawnictwo Muzyczne, 2002), p. 40.

- 9Oskar Hansen interviewed by Stanisław K. Stopczyk, Projekt, no. 1 (1965), pp. 8–10.

- 10Krauze’s Five Unist Compositions (Pięć kompozycji unistycznych, 1963) and Schaeffer’s Hommage à Strzemiński (recorded in the Experimental Studio of Polish Radio in 1967).

- 11Jerzy Hordyński, “Kompozytorzy współcześni. Krzysztof Penderecki” in Życie Literackie, 44 (1960), pp. 4, 8, cited by Danuta Mirka, The Sonoristic Structuralism of Krzysztof Penderecki (Katowice: Akademia Muzyczna, 1997), p329.

- 12“How much Rudnik is in Penderecki, and how much Rudnik is in Nordheim? Interview with Eugeniusz Rudnik” Warsaw available at post.moma.org starting January 28.

- 13Later in his career, Hansen created one important Open Form performance space in Warsaw when he was commissioned in 1972—with Piotr Damięcki, Henryk Górka, Stanisław Górski, Adolf Szczepiński, and Włodzimierz Witkowski—to renovate the Studio theater in the Palace of Culture. See Oskar Hansen, “To Break Down the Barriers between the Audience and the Actor” in Poland, 10 (1975), p. 38.

- 145x Galeria Foksal—PSP (Warsaw, 1966), n.p. Author’s translation.

- 155x Galeria Foksal—PSP (Warsaw, 1966), n.p. Author’s translation.

- 16The Spatial-Musical Composition (Kompozycja przestrzenno-muzyczna) created by Krauze and Morel with architect Teresa Kelm in Galeria Współczesna, Warsaw, in 1968, was another key installation that required the participation of its audience. See David Crowley and Daniel Muzyczuk, Sounding the Body Electric. Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957–1985 (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki, 2012), pp. 146–52.

- 17For discussion of Polish art in the 1970s, see Luiza Nader, Konceptualizm W PRL (Warsaw: Foksal Gallery Foundation, University of Warsaw Press, 2009); Piotr Piotrowski, Dekada. O syndromie lat siedemdziesiątych, kulturze artystycznej, krytyce, sztuce—wybiórczo i subiektywnie (Poznań: Obserwator, 1991); Łukasz Ronduda, Polish Art of the 1970s (Jelenia Góra: Polski Western; Warsaw: Centre for Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle, 2009).

- 18Interview with Krzysztof Szlifirski by the author, Warsaw, 2010.

- 19Krzysztof Wodiczko: Pojazd / Vehicle (Warsaw: Foksal Gallery, 1973).

- 20This discussion of Product and Instrument–Percussion Laboratory is indebted to Łukasz Ronduda, “Krzysztof Wodiczko-Projektowanie I Sztuka,” Piktogram, 7 (2007), pp. 12–27.

- 21Krzysztof Wodiczko, “Instrument–laboratorium perkusyjne” in Res Facta, 5 (1971), p. 185. My emphasis. Author’s translation.

- 22Miklós Haraszti, The Velvet Prison. Artists Under State Socialism (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1989)

- 23The invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces on the night of 20–21st August 1968 brought about the end of the liberalizing movement in the country. This event shattered the hope held by many Eastern European intellectuals inside and outside Czechoslovakia that Soviet style socialism could be reformed and accelerated the spread of dissent in the region.