This text was originally published under the theme “Polish Radio Experimental Studio: A Close Look”. The theme was developed in partnership with Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź (MSŁ). It was edited by Magdalena Moskalewicz, MoMA with Daniel Muzyczuk, MSŁ. The original content items in this theme can be found here.

My specialties were films about love, about motherhood, death, martyrology, or the funereal world, illustrated with concrete music. In my shop I would compose music for any film on any human subject. I tried to generate, find, or invent sound, the character of which was new and did not call up any associations, because as soon as someone takes up instrumental music, the listener immediately sees the chandeliers and marble of the philharmonic. My music should only be related to the image and give those associations that I want under the influence of the audiovisual impulse. In this interview conducted especially for post, Eugeniusz Rudnik—a lifelong sound engineer of the Polish Radio Experimental Studio—speaks about the early years of Polish electroacoustic music, about his distrust of both musical scores and the deceptive idea of musical and artistic progress, and about the fine line between sound engineer and composer.

Daniel Muzyczuk: It is the prevailing opinion that Polish Radio Experimental Studio was to a certain point a safety valve. Set up during the “Thaw”1The term “Thaw,” taken from the title of Ilya Ehrenburg’s 1954 novel, refers to the period following Joseph Stalin’s death in March 1953, when Nikita Khrushchev introduced policies of de-Stalinization, which eased repression and censorship in the Soviet Union and many countries of the Soviet Bloc. In Poland, October 1956 was the critical moment of the political and cultural “Thaw.” alongside the Warsaw Autumn Festival2Founded in 1956, Warsaw Autumn Festival is Poland’s largest festival of international contemporary music., it was taken as a sign of an opening to experimental music on the part of the authorities during the era of the People’s Republic of Poland (PRL). Do you regard its establishment as a political act, with a certain political role to fulfill?

Eugeniusz Rudnik: This was an absolutely remarkable period in Polish culture. I had been working in radio since 1955, and this “Thaw” passed through my own hands. I’ll tell you straightaway what I have in mind. Beyond all doubt, looking today at the role of the Experimental Studio in our culture, in the history of our music, and in our radio history, the Thaw played a role of unheard importance. I am proud of that, not because of megalomania or narcissism, but because I had the good fortune to come into contact with the director and founder of the Studio, Józef Patkowski. He played a crucial role. We were a kind of window onto the world. This was an unusual thing—that in this period of what many call “heavy communism,” which included martial law, the Experimental Studio was an exception. We had uninterrupted two-way contact with the whole world. Our works were played at concerts organized in South America, in Europe, in Australia, in Asia, and in Japan. Requests came for the performance of works from the Studio. We did not even have to go through the Office of International Cooperation, where there was censorship. The ladies who worked there sent packages to Japan, because sending was quite expensive, but no one dared ask what was inside. Now, as one of the few people of my era who engaged in the creative arts at that time, I ask myself a dramatic question: Did the creation of art ennoble that empty shell of a state? Should I be proud of that? Or should I be ashamed that I legitimized it to the world, with my own hands, as the producer of these works?

To the first question, I answer, “Yes, of course.” The presence of our works, which were technically and artistically on a par with the fine products being produced in Paris, Milan, or Utrecht, meant that Poland was alive. The same question could be asked of Andrzej Wajda or Kazimierz Kutz. Was it worth making art? Yes, it was worth it, and it was needed. Fortunately, we created works that lasted, that successfully function today in the free world, in free Poland.

Muzyczuk: Let’s come back to Józef Patkowski. I am interested in the moment when Patkowski conceived the idea of the Studio. He started to shape it into a reality, to go from office to office, but surely also to travel and collect information—from Paris, for example—did he not?

Rudnik: Józef Patkowski was a musicologist who had been a student, protégé, and—perhaps while still a student—an assistant of Zofia Lissa. She was the chair of musicology, and at that time single-handedly ruled Polish music. Patkowski—my boss, my friend—was a well-educated person. His father was a professor in Wilno, where, they say, he organized the physics department. At that time, after October 1956, Józef was one of the few Polish Radio employees who had been abroad. Włodzimierz Sokorski, who was a very unusual figure, had been designated as the head of Polish Radio. He appeared to be a person of imagination. It turned out that Józef Patkowski had a passport in hand, acquired with some difficulty. He traveled to Paris to take a look at the radio studio organized there in the 1940s by Pierre Schaeffer, nota bene, a sound engineer. Patkowski worked at Polish Radio as a consultant, advising Polish Radio Theater. To put it frankly, he was selecting music for radio plays. When he returned to Warsaw, he apprised Włodzimierz Sokorski of the need to organize a unit such as Schaeffer’s. Sokorski, who was a pure party functionary, although I have no doubt that he was a gentleman of exceeding intelligence, created the Experimental Studio and protected it for years from elimination, because we reported directly to the president. There was a phenomenon, particularly in Polish Radio, of following a certain pragmatics: division, department, office, section, division, editorial board. The Studio was the president’s sacred cow. Sokorski reported to him through the presidential secretary. Patkowski was appointed as the Studio’s director. A few days later I became the only employee of the Studio. A week after my transfer from the technical section to the Studio, I started to produce the first work commissioned by the Experimental Studio. This was Włodzimierz Kotoński’s Etude for One Cymbal Stroke.

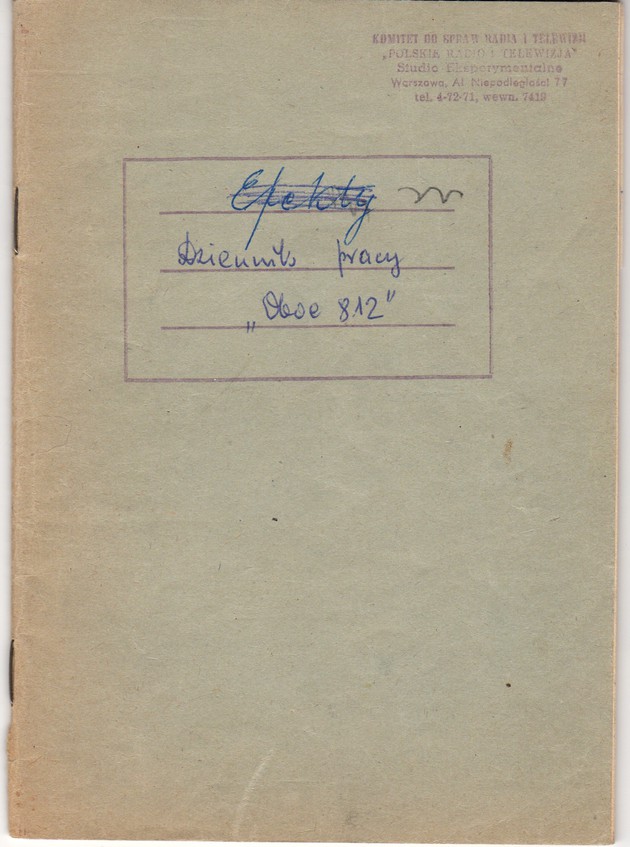

Thus began my collaboration with Patkowski, and thanks to his intelligence and access to the world, the Studio started to function as a valuable, self-respecting outpost in the circle of European studios of electronic music. Our studio was distinguished by the fact that the composer worked with the sound engineer, and not alone. Labor costs in People’s Poland were always low (just like now, when compared to the rest of Europe), thus Poland was able to employ me full time, and later, my colleague Bohdan Mazurek as well. The composer had total luxury. He would go to the specialist, who could edit tape for him with scissors, push the buttons, and know why he was pushing those buttons. Some composers had bit of familiarity with the technology, and that was unfortunate, because they started to act smart and try to teach us which buttons to push. They were sharply put in their place. As a result, we made minor or major works—I called them “mmw” or “major minor works”3This is a play on words. Rudnik used the term “dziełko,” a diminutive of “dzieło” (artwork, or art piece), and added the adjective “major” [główne]. (Editor’s note)—that conformed to the high standards of the time and that were well crafted in the compositional sense. I worked without pause making incidental music, film music, music for radio plays, etc.

Muzyczuk: In Patkowski’s conception, such hybridity was fundamental to the functioning of the Studio, which on the one hand generated autonomous compositions, and on the other, was involved in mass production for radio, television, and film. This activity in two creative spheres was completely alien, for instance, to Pierre Schaeffer’s way of working. Maybe Patkowski’s genius lay in creating this hybrid foundation. The Studio would not have worked if it had been oriented exclusively toward autonomous music.

Rudnik: For us, incidental music for the Polish Radio Theater, the dramatic stage, Polish Television Theater, exhibitions of this or that, was just as important as autonomous music. Especially because in Western studios, incidental music was regarded as something inferior. Józef Patkowski realized that they were of equal weight. He was right, because how could anyone distinguish music composed for the Polish Radio Theater from autonomous music? Our contributions to the creation of non-autonomous art were heard by millions of listeners, while special concerts of autonomous music at the beginning of our operation may have had only thirty to fifty listeners in a small room in the basement of the National Philharmonic. However, I will not hide the fact that I learned a great deal about technology and composing by working with the theater directors who came to me for consultation and who used my music. No one expected that genius would arrive and that everyone would be inspired to create a masterpiece. The term “hackwork” was unknown to us. I treated a director making his debut in Television Theater with the same attention and respect as a famous film director or a famous composer. Our next client was the then-little-known Krzysztof Penderecki, with whom I worked on Psalmus 1961, a very important work that is still heard all around the world today. Apropos of which, Krzysztof Penderecki, today or yesterday or three years ago, in countless interviews or in his texts, always, or almost always, mentions that he was very grateful to the Studio and that he had learned a great deal there. We made not only the work Psalmus 1961, but also ten or twenty or thirty or forty or more incidental compositions for film shorts, animations, and documentaries.

The period of the 1960s was the golden age of Polish short films. As we may now see in DVD compilations of the films of Daniel Szczechura or the films from Bielsko or the Semafor studio in Łódź, the most famous of the works by these directors passed through my hands in the Studio, first when I was a sound technician and later when I was composing. Three years ago, there was an interview with Krzysztof Penderecki, “I Take the Rocky Road,” in which he said the following:

“I treat the word ‘progress’ in relation to art, to music, with suspicion. Gregorian chant is not particularly more primitive than the concerto or sonata. It is different, but not worse. The avant-garde had a style. It was connected to technical discoveries and is particularly the time of the great explosion of electronic music. When they opened the Experimental Studio, I went there at once. My right-hand man there was Eugeniusz Rudnik, an engineer of great creative imagination who later began, himself, to compose, and if it were not for my time in the Studio, I would not have written my Polymorphia. For instance, the Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima in general doesn’t sound like a string orchestra, but rather like electronic music—this is due to my experience in the Experimental Studio.”

Do I not have the right to burst with pride because Krzysztof Penderecki wrote such things? He has frequently written “the Studio . . . Studio . . . Studio,” and then, suddenly—he recognized not this or that person—he saw fit to mention my otherwise humble name.

Muzyczuk: Patkowski’s invitation in 1962 to the architects Oskar and Zofia Hansen to redesign the interior layout and plan of the Studio attests to an unusual ambition to create a unique space for experimentation. I am curious to know in what manner this collaboration with the Hansens proceeded and what fundamental principles guided them and Patkowski. And from the other side, how functional was the Studio they designed?

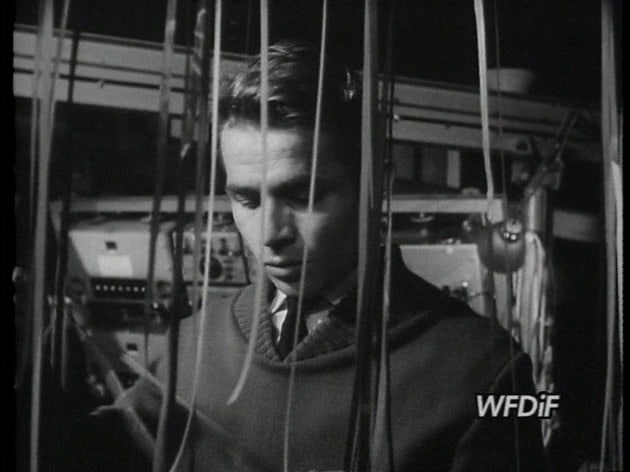

Rudnik: What I will now say will be iconoclastic, because Oskar Hansen is something of a cult figure. Some associate the Studio more with Hansen than with Patkowski, for instance, or with other names that I am too modest to mention. Józef was able to procure big money for the design of the interior of the studio4Rudnik used the word “wychodzić” (to walk out). This expression is very specific to the context of socialist Poland, where, in order to get anything done, it was necessary to make repeat visits to numerous offices of state administrators. Rudnik says: “Józef was able to walk out big money.” (Editor’s note). In its original form, the Studio was a space where so-called mixers, or sound directors, recorded multilingual programs for Europe. Józef Patkowski had the worthy and respectable ambition to create a space, a special workshop, an interior, and to arrange a workshop for electronic music composers, which was an unheard-of phenomenon. He wanted to create a work space that would dazzle the world with its functionality and its architectonic qualities. Hansen undertook this work. Krzysztof Szlifirski, who was the technical director of the Studio, joined him, and they worked on a design for a space that was too small, that couldn’t have been good. They redesigned the Studio to be full of newly discovered architectonic concepts, but they did not have a deeper sense for me or for the clients who came to work with me and who often worked three days and nights without pause. Hansen wished to allow the composers to design the aesthetic qualities of the walls, which were equipped with rotating elements with different acoustic qualities, different levels of sound absorption, and different colors. When we began stereophonic recording, we placed two speakers in the corners of this room. The longest dimension was six meters. Between the speakers was a space no greater than four meters. If I worked for twenty-five hours without a break in this little room, where the tubes were radiating heat, and it was the middle of the summer or a June night, I had to open the windows. Eighty meters away, cars were driving by on Malczewski Street, and so I could either listen to electronic music or to the rumble of a tractor. Of course, the Studio was photogenic, but it was not good for work, because the space was too small. Hansen’s Studio had to fill the functions of a room for playback, editing, recording, etc.—at least four functions in one space—and it was impossible to do all these things.

Muzyczuk: The Studio sporadically made recordings.

Rudnik: Almost never with microphones, but as we introduced the technique of contact microphones, where one could stick a small microphone with a tack to a spring or to a glass bottle, I could even record in the radio corridor, and I wouldn’t have to go for my keys or lose any time with this procedure.

Muzyczuk: The sound engineer was considered a “performer” in the Studio. That is a rather interesting use of the term, because actually he is the creator of a certain concept, often a hazy idea.

Rudnik: Intention is not always expressly laid out in words. Sometimes it is necessary to squeeze out what a composer has in mind. When a client arrived, I treated him with the greatest respect. Nowadays, I am sometimes asked some tricky questions: “Eugeniusz, how much Rudnik is in Penderecki, and how much Rudnik is in Nordheim?” I don’t know, because I never measured. I made the piece, but there were certain rubrics in the specifications: composer, performer, or sound engineer.

Muzyczuk: Somewhere in the mid-1960s, both you and Bohdan Mazurek transformed yourselves from engineers or performers into composers. That is an interesting evolution.

Rudnik: Interesting, but not so innovative. In such cases, I usually cite Thomas Mann. He said that music is such a phenomenon that it can defy all the very strictly defined and academically described truths and start anew from the beginning without regard for previous rules. And that’s how it was with electronic music. It was a school of inveterate experimenters who totally threw out everything that existed until that time. The truths, rules that we started to observe in electronic music—they were fashioned with these hands. The aesthetics and engineering and established forms were not defined a priori. And no one said that there should be such sections as in a symphony, no. Maybe that is why I was the first to turn away from the enchantment of the sonorists, from the euphoria they generated with each a new treatment5Sonorism is an approach to musical composition that focuses on the characteristics and qualities of sound—timbre, texture, articulation, dynamics, and movement. The term is restricted to Polish music from the 1960s.. Because a treatment is a treatment, and in music, form is the most important thing. Bogusław Schaeffer said that a musical work is above all form. It must have a beginning, a middle, and an end, as well as a good title. The disease of experimental music was the desire of composers constantly to enchant or torment the listener with unpredictable events. I am striving for the listener to be able to follow my reasoning.

Muzyczuk: In your work and in Bohdan Mazurek’s, there appears to me a clear struggle against sonorism. Let’s consider, for example, your very frequent use of repetition. I have the impression that after struggling all day with these sonorists, with their non-repetitive compositions, you worked in the evening on your own pieces in reaction against their rules.

Rudnik: I have a few works that I made out of spite for composers who were crazy for Stockhausenism. Poles tend to be stupid: if the Germans do something, it means it must be done that way, because the cultural influence of Germanness has always been meaningful to us. Tempos must be set to two decimal places. I composed a good work, which was called Dixie, almost in real time. Back then, the category of real-time composition was unknown. I went up to the tape recorder, turned it on, did something, and then I cut and trimmed. In the same way, I made our first collage that lasted precisely in real time. I didn’t have to fight with noise, because noise is also an acoustic phenomenon and may be treated as useful material.

Muzyczuk: I’d also like to ask you about your very particular working method—I mean, the treatment of outtakes and seemingly useless scraps as fundamental material.

Rudnik: It wasn’t I who came up with the readymade. At a certain moment, it was as if I needed to cross over to the other side. How do we suddenly find this particular sound good, nice, pretty, worth including in the piece? I find something remarkably interesting in the work of those artists who build collages. I believe that if an artist goes up to a wastebin and sees a doll that’s missing an arm as well as a stroller without a wheel, and he takes that stroller, and lays that doll in it and fills it with soil—each of these three elements is trash that is useless to anyone, but constructed into this visual whole, they begin to become something particularly important and intriguing6Rudnik is most probably referring here to the assemblages of his contemporary Władysław Hasior. The work described seems to be Hasior’s. Therefore, I have my shabby materials, those malapropisms that slipped from a statesman’s tongue, or from the bishop as he gave his sermon. In them, there is a person’s most truthful truth—in the slips, in the auditory or acoustic exposition, speech, or oratorical description. I sometimes perversely, but not sadistically, penetrate these regions; I listen to kilometers of such recordings, to show that human powerlessness, that human greatness, and at the same time, that weakness. We are only so great, so strong, as we are weak. Indeed we may fall having slipped on that threshold and die as we hit our head against the wall.

Muzyczuk: Could you tell me about the tendency of Bogusław Schaeffer to record, or also to compose, the same compositions several times? For example, Symphony—electronic music has at least a few different versions. I am interested in how Schaeffer arrived at the poliversionality of his compositions. This is rather rare in music for tape.

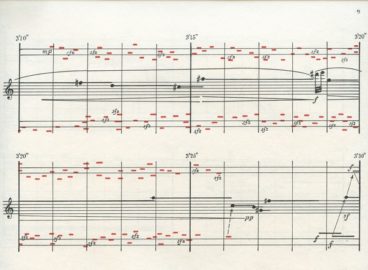

Rudnik: I’ll tell you about one case with Schaeffer that shocked me. It was the strangest task that fell into my garret, or into the black room of the Studio. I was working with him on his great work, Missa electronica, which in my opinion is underappreciated. Of course, I worked with him very intensively, as he never touched the console, never defined what he wanted to hear. I made various proposals to him. At a certain moment, Schaeffer spoke, delivering the longest oration he made during his collaboration with me. He said: “Mr. Eugeniusz, for me, the sound is not important. As with the poet, for whom it is irrelevant whether he writes his greatest poetry on the back of a napkin in a bar or on parchment.” Schaeffer, through his ever-bursting imagination, sketched out triangles, squares, rectangles, parallelograms, in two systems of coordinates: volume/time, pitch/time. Or, in a precise manner, he determined the two parameters of pitch and duration. The indeterminacy of Schaeffer’s scores is great for me. We know nothing of the treatment of the sound or its color. I am anti-score. I don’t know where the unusual cult of the score comes from in electronic music. Of course, you can repeat after the theoreticians and the musicologists that if there is no score, there is no music. This rule lasted until 1948, when Pierre Schaeffer began to improvise.

Muzyczuk: I’d like to peek under the lining at the motivations that brought film directors to the Studio. At the moment the Studio was established, and somewhere into the mid-1960s, filmmakers felt strongly about the characteristic futuristic gurglings that they might use in film adaptations of the works of Stanisław Lem—for example, Silent Star [1959], and other science fiction films. As soon as a computer appears on the screen, the sounds of the tape blare forth. This changes over time. The filmmakers’ motivations become less clear, and slowly the sounds from the Studio are incorporated, even into psychological dramas. What sounds were filmmakers looking for?

Rudnik: What you are saying is revealing. No one other than you has formulated it this way. As I see it, filmmakers would come to me wanting either the cosmos or Hades. They would rush to ol’ Gene to work it out. This was the first primitive step in understanding the potential of this music. It all came from this, that the first great work of incidental music to come out of the Studio was Silent Star after Lem with the music of Andrzej Markowski. At a certain moment, I stopped providing these gurgling-cosmic or Hades-underworld services because they were making me sick. My specialties were films about love, about motherhood, death, martyrology, or the funereal world, illustrated with concrete music. Then cosmic gurgling fell out of fashion, and I simply was doing it with disgust. In my shop I would compose music for any film on any human subject. I tried to generate, find, or invent sound, the character of which was new and did not call up any associations, because as soon as someone takes up instrumental music, the listener immediately sees the chandeliers and marble of the philharmonic. My music should only be related to the image and give those associations that I want under the influence of the audiovisual impulse. That is why artists came to me four at a time, sometimes on their knees.

Muzyczuk: As long as we’re on the film industry, maybe we can move to the avant-garde, because I am interested in the Studio’s encounter with the Workshop of the Film Form7The Workshop of the Film Form (“Warsztat Formy Filmowej”, also called Film Form Studio), was composed of neo-avant-garde filmmakers based in Łódź between 1970 and 1977. Among the members were Józef Robakowski, Wojciech Bruszewski, and Ryszard Waśko.. At the end of the 1960s there was sporadic contact between you and Józef Robakowski as well as Zbigniew Rybczyński. You were invited together with Józef Patkowski to the Kino Laboratorium in Elbląg8Kino Laboratorium was a section of the Biennale of Spatial Forms in Elbląg in 1973. It was organized and programmed by members of the Workshop of the Film Form.. It seems to me that you were connected by a method of work based on structure and the ethics of working with tape or film, and not only by pure aesthetics.

Rudnik: The artists whom you have named were avant-gardists in the strict sense. They rejected the classical form of film. They were no longer interested in drawing thousands of frames. They clung to me with enormous passion because they rejected both form and appearance, as the filmmakers say. A filmmaker who came to me did not hear the piano, guitar, or saxophone, but instead heard, what I called in my treatments, “creakings” that were from a completely different world. When, excited by a director’s images, I could find the connections between his abstract world or his paranoid world or his reinterpretation of the world and my music, he was completely happy. Of course, what I could propose was a precise correspondence between the music and the image.

Muzyczuk: An interesting commentary on what you have told me about the cooperation between you and, for example, Rybczyński, when it was the director who ordered music from you for a prepared film, is Józef Robakowski’s Dynamic Rectangle, in which the situation was completely reversed. From what I know, he received a tape from you that he wanted to illustrate in film.

Rudnik: This is a remarkable thing. While I was making music, I would hear from these directors specializing in short or experimental forms: “How good it would be, if I could first get the music, and then could edit a film over it.” I think it is exciting that, if you have a basis in sound in which time is structured, where there are accents, then the sound is asking to have an image pinned there.

Muzyczuk: In conclusion, I’d like to ask you about one more thing. The Experimental Studio existed for almost fifty years. I wonder how much you can say about the transformation and evolution you witnessed over this period. Can it be summarized by saying that change was driven by new technologies?

Rudnik: The apogee of our glory was reached roughly one-third of the way through the Studio’s lifetime. The 1960s and the beginning of the ’70s were a remarkably lively period in Polish culture. Censorship had grown weak. Just as every structure has its birth, period of struggle and conflict, apogee, and then its decline, so it was with the Studio. Theoretical works were planned; there were supposed to be books, academic studies, etc. There was someone who undertook the archiving and promotion of the Studio. That activity concluded with there being no archive of the Studio, because it was lost. Nothing was done beyond the publication of a book from Józef Patkowski’s broadcasts of Musical Horizons on Polish Radio 2. At the beginning, we had a budget and we could commission compositions from Penderecki, Schaeffer, or Krzysztof Knittel, who had broken into the composers’ market. When Polish Radio started to talk more and more loudly about funding shortages, we were paid less and less in the Studio, but tolerated. Krzysztof Szlifirski approached five directors to provide us with a computer, because it was assumed that an analog studio must evolve toward computerized music, but it didn’t evolve. The Studio was eliminated in an inelegant manner; the archive was lost. I worked with Bolesław Błaszczyk for four years to organize the products of the Studio, which against orders, I did not throw in the trash. These are mainly documents (originals and copies) concerning my compositions and professional activities in the country and abroad. I have these notebooks displayed, and I took the tapes to my house in the country. I keep them inside my couches while a team of three people should come over and say: “Mr. Eugeniusz, you are the last one still alive who knows so much about the Studio. Please take a seat and we will record not only an interview stream, but also an ocean of interviews. And please show us your written and audio archives. Please tell us what you know about this work and this one.” Because in just a moment, to any half-intelligent music and radio journalist, I will be a name and a title and nothing more. And well—only that I am neither a theoretician nor a scholar of culture. I am a poor and aged engineer and composer, but I think that I know a lot. Amen.

(February 2013)

Translated by David A. Goldfarb

Translation revised and annotated by Magdalena Moskalewicz

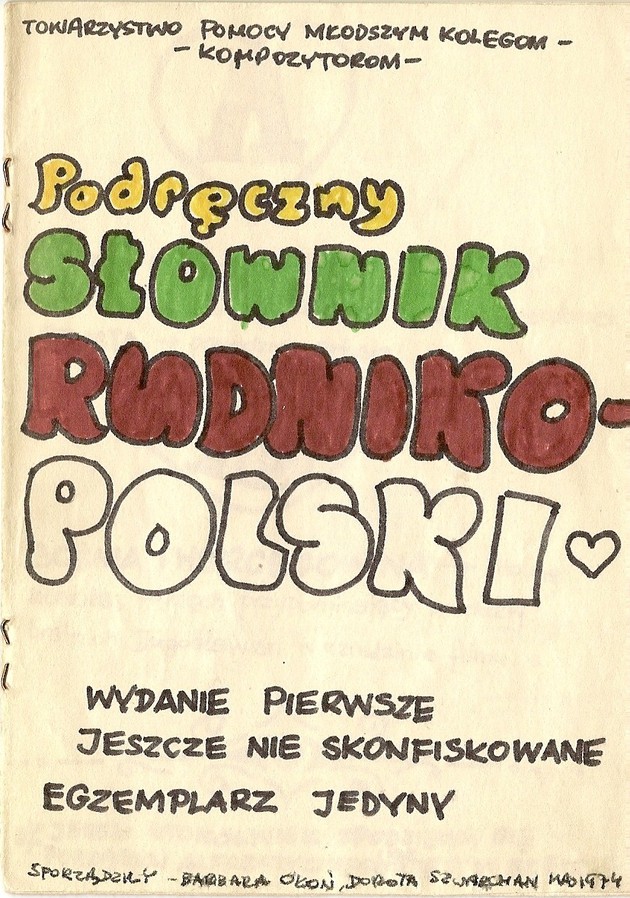

Czarny Krajobraz I – Dzieciom Zamojszczyzny (1974).

The Polish version of the interview is available here.

- 1The term “Thaw,” taken from the title of Ilya Ehrenburg’s 1954 novel, refers to the period following Joseph Stalin’s death in March 1953, when Nikita Khrushchev introduced policies of de-Stalinization, which eased repression and censorship in the Soviet Union and many countries of the Soviet Bloc. In Poland, October 1956 was the critical moment of the political and cultural “Thaw.”

- 2Founded in 1956, Warsaw Autumn Festival is Poland’s largest festival of international contemporary music.

- 3This is a play on words. Rudnik used the term “dziełko,” a diminutive of “dzieło” (artwork, or art piece), and added the adjective “major” [główne]. (Editor’s note)

- 4Rudnik used the word “wychodzić” (to walk out). This expression is very specific to the context of socialist Poland, where, in order to get anything done, it was necessary to make repeat visits to numerous offices of state administrators. Rudnik says: “Józef was able to walk out big money.” (Editor’s note)

- 5Sonorism is an approach to musical composition that focuses on the characteristics and qualities of sound—timbre, texture, articulation, dynamics, and movement. The term is restricted to Polish music from the 1960s.

- 6Rudnik is most probably referring here to the assemblages of his contemporary Władysław Hasior. The work described seems to be Hasior’s

- 7The Workshop of the Film Form (“Warsztat Formy Filmowej”, also called Film Form Studio), was composed of neo-avant-garde filmmakers based in Łódź between 1970 and 1977. Among the members were Józef Robakowski, Wojciech Bruszewski, and Ryszard Waśko.

- 8Kino Laboratorium was a section of the Biennale of Spatial Forms in Elbląg in 1973. It was organized and programmed by members of the Workshop of the Film Form.