This text was originally published under the theme “Polish Radio Experimental Studio: A Close Look”. The theme was developed in partnership with Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź (MSŁ). It was edited by Magdalena Moskalewicz, MoMA with Daniel Muzyczuk, MSŁ. The original content items in this theme can be found here.

Just as alchemists in the Middle Ages were the masters of arcane knowledge, so the core members of the Studio—the sound engineers—were masters of new technology in music. Let us look into the written records of their sacred knowledge: the music scores.

The artist’s studio—and the musician’s in particular—has always been an alchemist’s cabinet. And the visitor—not to be confused with a snob—has never been interested in how it [art-making] was done. The visitor wants to feel something and not study something—even if [the art is] loaded with technical issues, [the visitor, without a basic understanding of these, would be,] perhaps, cheated.”1Eugeniusz Rudnik, “Sympozjum ‘studyjne’ na temat technologii,’’ in Magda Roszkowska, ed., Studio Eksperyment: Leksykon. Zbiór tekstów (Warsaw: Bęc Zmiana, 2012), p. 40.

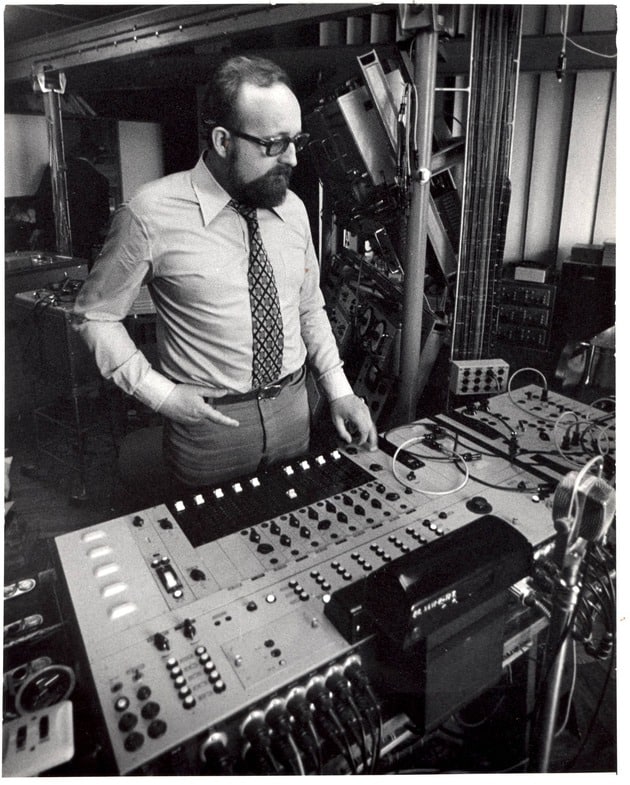

The casually spoken words of Eugeniusz Rudnik seem to me to provide a remarkably accurate introduction to a history of Polish Radio Experimental Studio (PRES). At the time of its founding by Józef Patkowski in 1957, the Studio was Radio’s most progressive and ambitious project. From today’s perspective, it seems to have been a marvel of a very peculiar nature, and this nature is nimbly summed up by Rudnik. The Studio’s famous Black Room was designed to be known for its output—the sound recordings that emerged from it—and not for the methods employed by those who worked there. Indeed, a kind of alchemy has been afoot here: for more than half a century, considerable effort has been made to shroud the Black Room in darkness—to turn its history into a mystery and its legend into a myth. Just as alchemists in the Middle Ages were the masters of arcane knowledge, so the core members of the Studio—the sound engineers—were masters of new technology in music. Let us look into the written records of their sacred knowledge: the music scores. These shed light on the experimental approach that prevailed in the Studio’s inner sanctum.

Experiment

In an interview published in 1987, Magdalena Radziejowska asked Józef Patkowski to identify the Studio’s most distinguishing trait. Patkowski replied: “[It is] most of all its technological and programming independence. The Studio was conceived as an instrument, a sound laboratory whose apparatus is available for use by composers together with sound engineers and the engineers who design the equipment. Together they assemble data from which a composer can create his idea. And this is exceptional worldwide. There are no composers on the Studio’s board or crew. There are only specialists of sound design.”2Józef Patkowski in conversation with Magdalena Radziejowska, in Studio Eksperyment, p. 93. One can sense a barely hidden philosophy of experimentation in Patkowski’s words. The Studio was not about aesthetics; it was about data. It was not only about skills and craft, as in art; it was also about knowledge and procedures, as in science. This amalgam was enclosed in a small room full of the latest technology. Equally mysterious were the amazing skills of the Studio’s crew. “The buzzword ‘experiment’ was not an empty term, thanks to the undogmatic approach of the sound engineers Eugeniusz Rudnik and Bohdan Mazurek, who were later also composers. Their courage in taking risks as well as their erotic bravery made the difference between them and other musicians who worked in the Studio and were trying to create sound that conformed to a priori ideas, hardly ever allowing ideas to flow directly from the creative encounter of a researcher and his material.”3Antoni Beksiak, “Dlaczego Eugeniusz?’’ available online www.culture.pl (accessed on June 10, 2013). What were they doing there? Still—scientific language: the recherches in Pierre Schaeffer’s Groupe de Recherches Musicales, the algorithms in Lejaren Hiller and Leonard Isaacson’s seminal book on computer music,4Lejaren Hiller and L. M. Isaacson, Experimental Music: Composition with an Electronic Computer, (New York: McGraw-Hill,1959). and the word “experimental” in Polish Radio’s Experimental Studio. One of the particularities of PRES that Patkowski neglected to mention was that it published nothing to introduce or simply describe its practices. Actually, it published almost nothing.

I used to think of this publishing lapse as a shortcoming or a scandal, but there may have been substantial reasons for it. The Studio’s independence, in which Patkowski took such pride, was at least partly due to its low profile. No one really understood what its engineers were doing. For more than fifty years, the only way to learn about the fruits of their labors was to listen to the radio or attend concerts. Rare concerts and rare radio broadcasts. Even in the 1990s, when recordings from GRM (Groupe de Recherches Musicales) and WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk) had attained the status of classics, and Schaeffer’s and Stockhausen’s manuals and blueprints were appearing on music academy syllabuses everywhere, not a single book or full-length album bore the imprimatur of PRES, which by that time had gone dormant. But there were scores.

The scores are not leaks. They give no insight into the sound engineers’ techniques. Yet they do contribute to an understanding of what was experimental about the Experimental Studio. Paradoxically, the presence at PRES of this conservative and perhaps even regressive musical tool tells a tale of an alternative way of experimenting. And even if the scores originated in the world of composers, their nature in this instance is comparatively open, clear, transparent—and published.

The status accorded to scores at PRES is ambiguous on many levels. The documents are a symbol of what, in the 1960s, was called “autonomous creation,” as opposed to “utilitarian creation,” which served film, theater, and radio soundtracks. Despite all that has been said, the Studio’s main pride lay not in the mysteries of the Black Room but in the list of critically acclaimed composers that it attracted from all over Europe: Włodzimierz Kotoński, Andrzej Dobrowolski, Krzysztof Penderecki, Bogusław Schaeffer, Arne Nordheim, Dubravko Detoni, François- Bernard Mâche, Lejaren Hiller, and others turned the Studio into a prestigious unit. Until 1965, every musical composition registered in the archives was by a professional, academically trained composer.

On the other hand, there are many reasons to think that scores were of little importance in the Studio’s actual functioning. First of all, consider their quantity. Of the hundreds of compositions registered in the Studio’s archive, few are scored. The exact number depends on how you count them: seven scores of what are essentially tape music compositions5Etude for One Cymbal Stroke and Aela, by Włodzimierz Kotoński; Symphony, by Bogusław Schaeffer; and Music for Magnetic Tape No. 1, Music for Magnetic Tape and Oboe Solo, Music for Magnetic Tape and Piano Solo, and Music for Tape and Bass Clarinet, by Andrzej Dobrowolski. were published, accompanied by recordings created in the Studio; a greater number of instrumental scores was issued, each followed by a tape prepared in the Studio; and dozens of unpublished sketches were produced by composers who used them to communicate their ideas to the engineers.

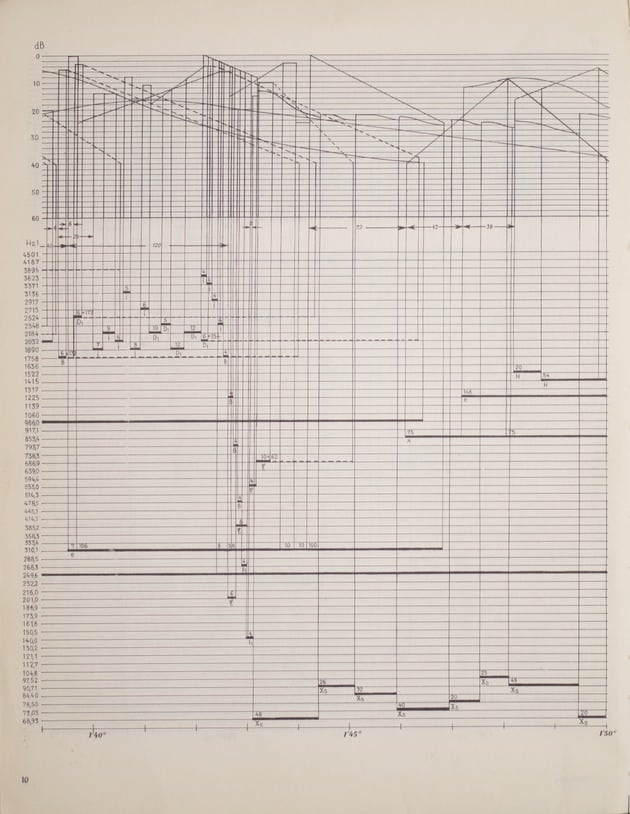

Second, consider the dates. The first electronic piece that Kotoński recorded in the Studio was his Etude for One Cymbal Stroke, in 1959. The score was published in 1972. “Electronic music that is controlled by the composer from its conception to its final recording seems to be the kind of music that can reach the listener in a way that precludes the unforeseeable, such as performers’ errors and other unpredictable events,” commented Barbara Makowska-Okoń, a sound engineer who started at the studio in the mid-1970s.6Barbara Okoń-Makowska, “Projekcja dźwięku,” in Studio Eksperyment, p. 147. If the ultimate idea of Kotoński’s Etude for One Cymbal Stroke was recorded on tape in 1959, why publish a score for the piece in 1972? So that it might be performed again? Another question mark. If we take a closer look at the score of this first autonomous piece conceived at PRES, we see that it reflects the inability of the composer to represent what Józef Patkowski described as the “sounds of new timbral qualities, new colors”7Józef Patkowski, “Perspektywy muzyki elektronicznej,” in Studio Eksperyment, p. 85. that suffused music experiments. The symbols and the setup were taken from what is today considered to be the first electronic music score ever published, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Studie II. What we have here is a graph with two coordinates: the vertical (organized in four simultaneous systems) charts frequencies and dynamic levels; the horizontal registers the passage of sound events.

Włodzimierz Kotoński, Etudia na jedno uderzenie w talerz (Study for One Cymbal Stroke), 1959. Published 1972.

But the rectangles, triangles, and trapezoids representing sound events contain no information about timbre or texture. This is because the sound quality in Kotoński’s piece has been documented in the form of a recording—it does not need to be represented. Hence, six out of seven passages in the written instructions for his Etude are given in the present perfect tense. “The sound material for this Etude has been produced . . . ,” “The recorded sound has been transposed . . . ,” etc.8Włodzimierz Kotoński, Etude for One Cymbal Stroke, (Warsaw: PWM, 1967). The score was not intended as a set of instructions for performing the piece, but rather as a score for listening, in the manner of Rainer Wehinger’s 1970 score for Ligeti’s Artikulation, composed in 1958.9Wehinger conceived the graphic notation for Ligeti’s composition twelve years after the piece was composed and realized on tape. Called Hörpartitur (Aural Score), Wehinger’s score was meant to guide the listener rather than the performer. Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Music and Discourse: Towards a Semiology of Music (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990). It is not surprising, then, that in the four decades since Kotoński’s Etude was published, it has been performed only once.

The deferred writing of the scores might explain why they were published at all. Most probably, Patkowski, perhaps believing that serious music is written music, requested them together with theoretical explanations of the pieces from composers who wanted their works included in the PRES archive of autonomous compositions. But, in fact, the scores were nothing more than a formality to be deposited in the archive and forgotten, while the real work was being performed in the Black Room.

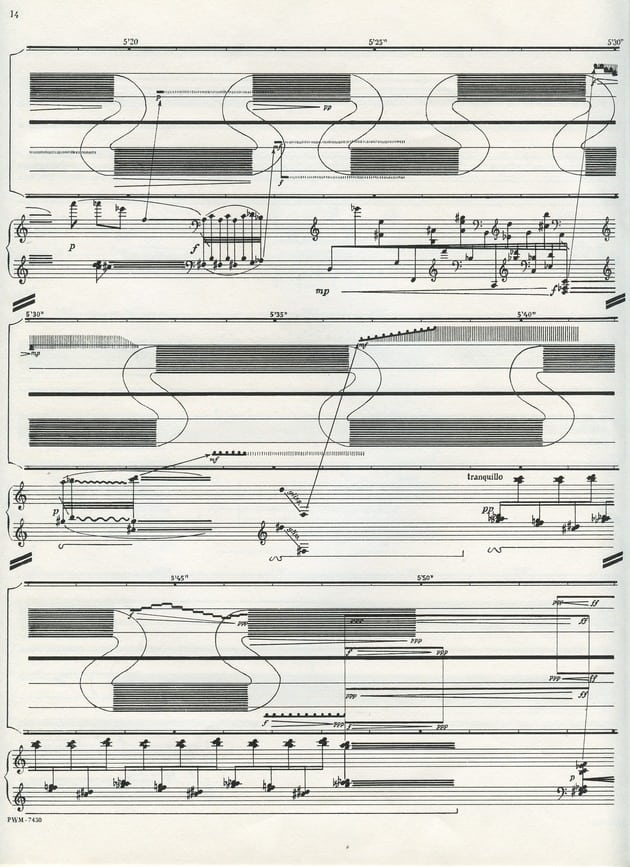

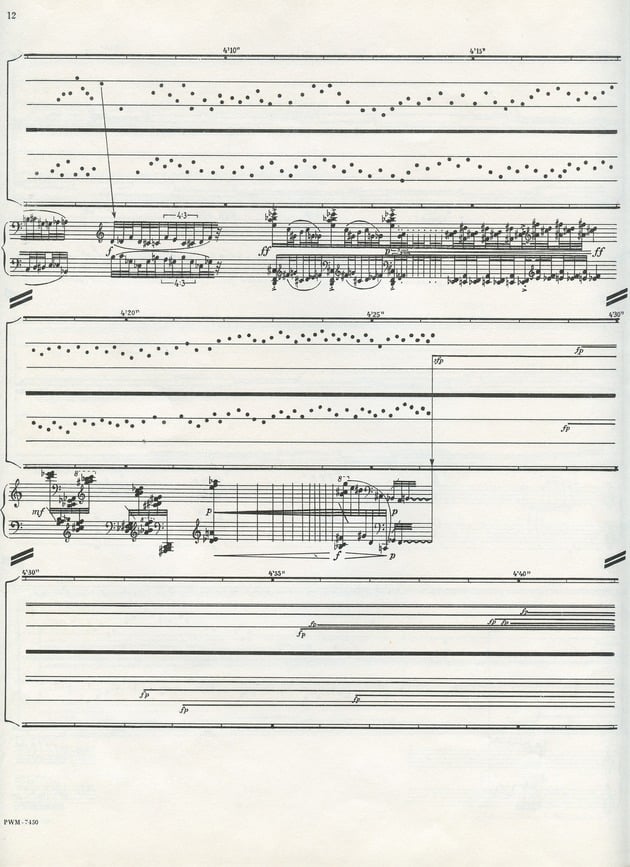

Andrzej Dobrowolski, Muzyka na Taśmę Magnetofonową i Fortepian Solo (Music for Magnetic Tape and Piano Solo), 1972. Published 1973.

Andrzej Dobrowolski was the composer who invested the most energy in writing scores at the Studio during the early years. Much more detailed and precise than Kotoński’s, the four pieces that Dobrowolski published at PRES together comprise the institution’s most complex blueprint for electronic music notation. Three of the works were scored for magnetic tape and a solo instrument: oboe, bass clarinet, and piano, respectively. Prior to these, Music for Magnetic Tape No. 1, printed by Music Publications Kraków in 1964, was the first electronic music score published in Poland. The fifty-page document contained sixteen pages of instructions and thirty- five pages dedicated to the score itself—all that to cover five minutes and sixteen seconds of electronic music composed from recorded and synthetic sounds. (Among the recorded sounds were sung vowels and piano strings resonating to a singer’s voice.) The charts of transformations are given, and then the score.

In his highly complex, ultra-precise scores, Dobrowolski created a paradoxical situation: the more experimental his compositions sound, the more detailed the score; and the more detailed the score, the less experimental the realization of the work in the Studio. What could possibly have been experimental in a sound engineer’s following the instructions for Music for Magnetic Tape No. 1? Since everything was written down in exacting detail, the engineer fulfilled the role of technician. He just needed to do the job. There was no need for alchemy, nothing to unravel, check or improve. The procedure was fixed; nothing was left to chance. Here, an experiment and a score were mutually exclusive. It was an either-or situation, a zero-sum game. Or, it was a vantage point from which to gain fresh understanding of the term “experiment.”

Experimental Score

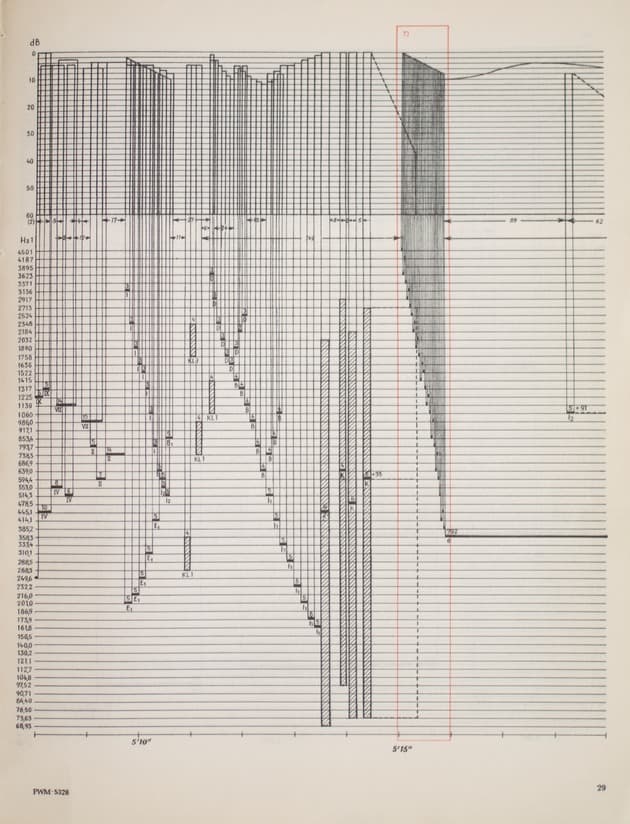

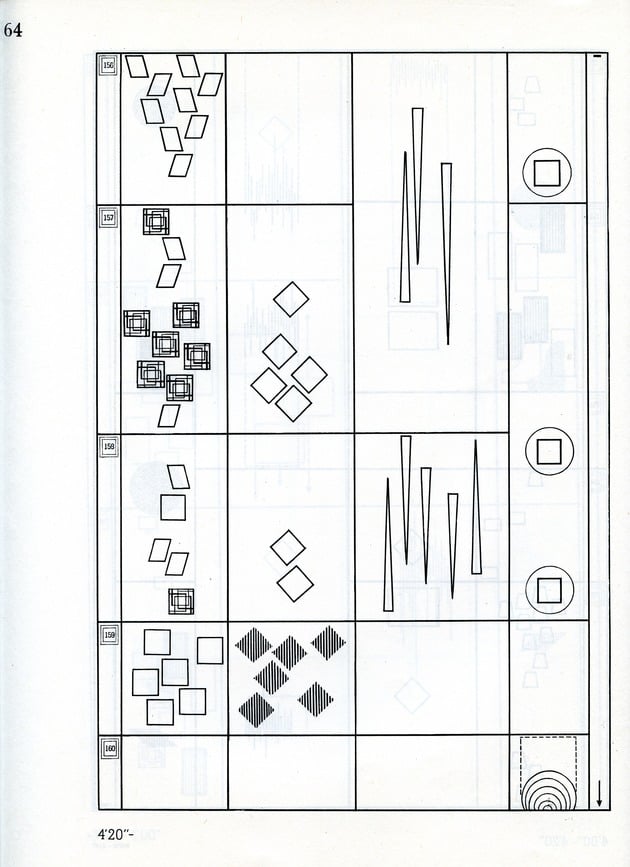

In the same year, 1964, Bogusław Schaeffer started working on Symphony, his electronic magnum opus, also known as Electronic Symphony. The score was finished two years later, and two years after that, it was published as a sixty-eight page book, including eighteen pages of instructions.

Bogusław Schaeffer, Symfonia: Muzyka Elektroniczna (Symphony: Electronic Music), 1964. Published 1968.

Symphony’s graphic score does not spark the visual/auditive imagination of the performer. Each of its elements is clearly defined, leaving no confusion about the meaning of the composer’s message, yet affording the performer a certain amount of freedom. That freedom lies first of all in exploring the potential offered by new technology. Schaeffer really addressed this piece to sound engineers, leaving it up to them to test how the meaning contained in the graphic notation can be transmitted by changing media. As Schaeffer himself commented: “In the development of music, particular elements move within the hierarchy of their functions—that is why Symphony has been and will continue to be interpretable.” Among the graphic signs, one finds symbols for sound events such as “pure tone + glissandi,” “different pitch levels + reverberation,” “a short beat, sharply finished,” “a shapeless, much deformed sound, indefinite in its pitch and substance—completely ‘anonymous’ material,” and “irregular tone-mixtures—described separately.” As Schaeffer indicated, it is up to the interpreter to decide how to execute a particular sign so that it will contribute more or less to the rhythmic or harmonic dimensions of the piece.

The sound events are prescribed for each of the symphony’s four movements and are organized in four simultaneous tracks indicated by boxes. The boxes are of different time lengths but form quite a clear pulse. The duration of the piece is given. In the end, then, the sound effects can be quite varied, depending not so much on the varied interpretations of the sound events (like “pure tone + glissandi”) but rather on the changing interpretations of the links between the determined and undetermined aspects of the score. Thus, one reading may result in four voices becoming one sound event, while in another they can subvert the time units set by the composer. In other words, the experiment here is rooted neither in the sound engineer’s skills nor in the final sound of the piece but in the disjunction of the two.

Experiment is no single person’s property, competence, or privilege. Just as Schaeffer’s work is over and done with, so any engineer’s work will be over and done with. But at their intersections, there will always be a slight misunderstanding that will generate new information.

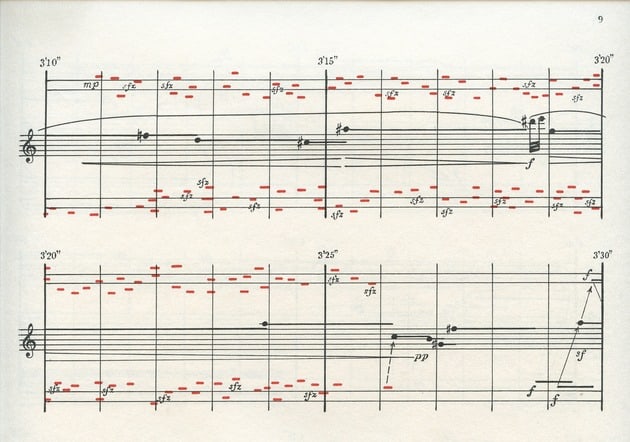

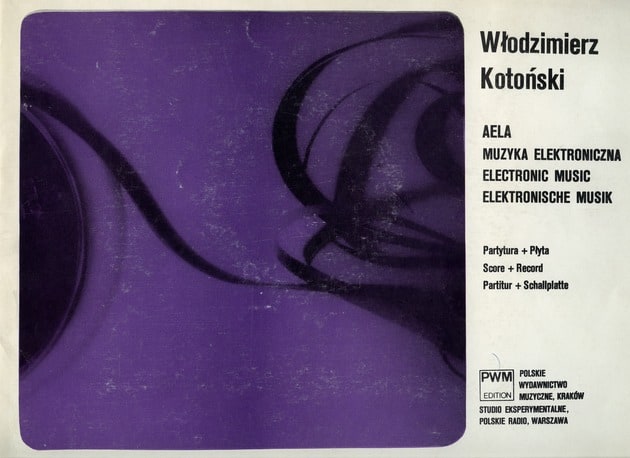

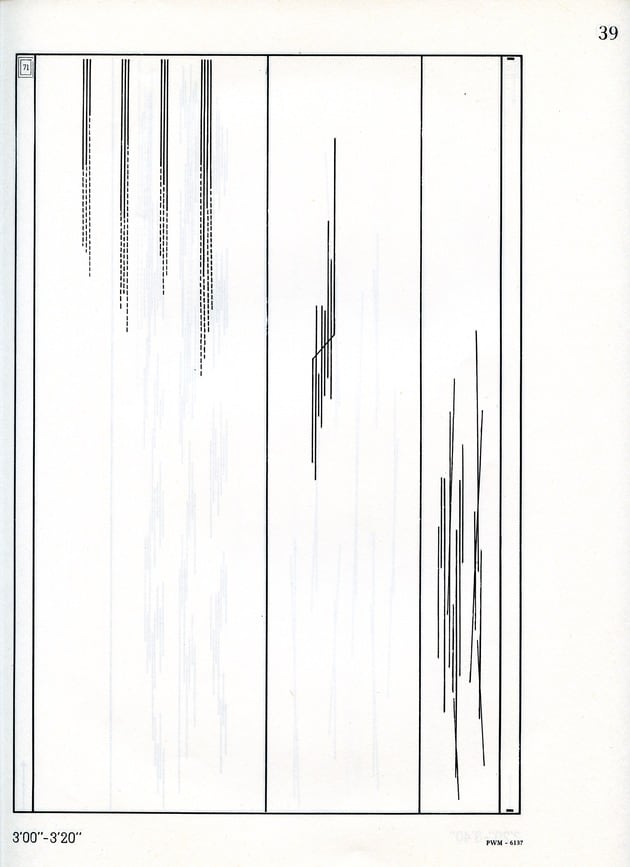

The most explicit experimental score of PRES was yet to come.Twelve years after publishing his first score at the Studio, Włodzimierz Kotoński published the score for Aela, a piece combining aleatoric10Aleatorism is a compositional technique of applying widely understood chance operations to define the parameters of a piece of music. and electronic music that he had released on tape five years earlier. The nineteen-page document is essentially a showpiece, a graphic complement to the written introduction that precedes it in the published volume. Not one of its graphic elements needs to be interpreted. A performer is meant to follow only the set of basic principles set out in the introduction. What Kotoński had in mind was not a piece as such but rather “a family of electronic pieces”11Włodzimierz Kotoński, Aela, (Warsaw: PWM, 1975). generated from the same clear principles and guidelines concerning sound material, frequency and time interval scales, sound intensity, spatial distribution, and aleatoric procedures. For example, the sound material consists entirely of sine waves—intervals of 25 Hz in the range between 25 Hz and 10000 Hz—but the actual sound material of the piece derives from the process of building it following the composer’s principles and guidelines. What the composer has designed is the framework within which a series of decisions is to be made and their interrelated consequences discovered. In Aela, the focus is not on the score itself, but rather on a clear and regular idea that the performer refers back to. No symbols are needed. All that is necessary is for the piece to be repeated by virtually anyone.

Experimental Performance

Symphony and Aela have in common the assumptions that no performance of the piece is definitive and that the work’s experimental nature is infinitely enduring. The point of these experiments is not merely to produce sounds that cannot be programmed or foreseen but also to dismantle with a score the black box of experimentality. In these cases, the score is an open agenda that fixes neither the substance of the work nor its effect. Unlike Kotoński’s aural score for his Etude and Dobrowolski’s detailed graphic transcription of Music for Magnetic Tape No. 1, which negate the experimental, Symphony and Aela trigger it off by embracing a philosophy of experimentation that is far from the scientific/alchemical ideas of arcane knowledge. With these scores we arrive at the definition of experimental music given by the composer John Cage, who called it a clear procedure that anyone can carry out, see the outcome of, and repeat over and over again. This is possible thanks to scores that are open invitations to experiment, as opposed to non-scored or closely scored pieces best realized in the precincts of the Experimental Studio. These two kinds of work represent divergent philosophies of experimentation: one is an open-source approach published in the form of an open score; the other is an alchemist’s black room, mysterious and inaccessible to all but the alchemists themselves—the sound engineers.

- 1Eugeniusz Rudnik, “Sympozjum ‘studyjne’ na temat technologii,’’ in Magda Roszkowska, ed., Studio Eksperyment: Leksykon. Zbiór tekstów (Warsaw: Bęc Zmiana, 2012), p. 40.

- 2Józef Patkowski in conversation with Magdalena Radziejowska, in Studio Eksperyment, p. 93.

- 3Antoni Beksiak, “Dlaczego Eugeniusz?’’ available online www.culture.pl (accessed on June 10, 2013).

- 4Lejaren Hiller and L. M. Isaacson, Experimental Music: Composition with an Electronic Computer, (New York: McGraw-Hill,1959).

- 5Etude for One Cymbal Stroke and Aela, by Włodzimierz Kotoński; Symphony, by Bogusław Schaeffer; and Music for Magnetic Tape No. 1, Music for Magnetic Tape and Oboe Solo, Music for Magnetic Tape and Piano Solo, and Music for Tape and Bass Clarinet, by Andrzej Dobrowolski.

- 6Barbara Okoń-Makowska, “Projekcja dźwięku,” in Studio Eksperyment, p. 147.

- 7Józef Patkowski, “Perspektywy muzyki elektronicznej,” in Studio Eksperyment, p. 85.

- 8Włodzimierz Kotoński, Etude for One Cymbal Stroke, (Warsaw: PWM, 1967).

- 9Wehinger conceived the graphic notation for Ligeti’s composition twelve years after the piece was composed and realized on tape. Called Hörpartitur (Aural Score), Wehinger’s score was meant to guide the listener rather than the performer. Jean-Jacques Nattiez, Music and Discourse: Towards a Semiology of Music (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990).

- 10Aleatorism is a compositional technique of applying widely understood chance operations to define the parameters of a piece of music.

- 11Włodzimierz Kotoński, Aela, (Warsaw: PWM, 1975).