Performances of Politics in a Nation-State (1991–98)

Armenian performative practices and “art actions”1“Art actions” is the term preferred by the young artists entering the scene in the 1990s. in the 1990s were characterized less by grand gestures of plentitude and excess and more by austere, minimal, and often barely visible acts engaging with the triviality of the everyday, intervening in “closed systems” of communication, overidentifying with or ironically repeating forms and procedures of the newly constituted liberal democratic state after the collapse of the USSR and its official rituals, and demarcating institutional boundaries of art. In the maelstrom of rapid transformations set in motion by the dissolution of the old world, many artists embraced the newfound quasi-anarchic freedom, the reestablishment of communication with the outside world, and the possibility of participating in the construction of the new world and new state. In the mid-1990s, for the first time, contemporary art from the Republic of Armenia was presented abroad under the aegis of its ministry of culture.2Official exhibitions were held in 1995 in Moscow’s Central House of Artists, in Bochum’s Galerie Bochumer Kulturrat, and in the Pharos Trust in Nicosia, Cyprus.The year also marks the first time the Republic of Armenia took part in the Venice Biennale; the Armenian Pavilion, which featured Samvel Baghdasarian and Karen Andreassian, was organized by the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art.In this context, the artistic avant-garde largely positioned itself as the self-appointed vanguard of the culture of the new state as opposed to a resistant subculture. Its agenda often (but not always) coincided with that of the cultural politics of the new republic—to represent Armenia as a progressive nation with an ancient culture that was finally joining the progressive and free family of nations on the international stage.

The 3rd Floor ultimately dissolved in 1994 in part because of a crisis of resistance3After the collapse of the USSR and throughout the construction of a new democratic state, artists largely embraced the official cultural politics. Hence, a certain crisis of resistance emerged in which it was no longer possible for self-identifyng avant-garde artists to maintain the ethos of negation of the dominant social order.but also because of the need to institutionalize, which came in conflict with the movement’s inherent anti-institutional stance, paving the way for a generation of artists who saw themselves as the avant-garde of the independent republic. This generation, which made its collective entry to the Armenian contemporary art scene in 1994–95 under the name ACT,4Naira Aharonyan, Hrach Armenakyan, Vahram Aghasyan, Narine Aramyan, Narek Avetisyan, Diana Hakobyan, Samvel Hovhannisyan, David Kareyan, Rusanna Nalbandyan, and Arthur Vardanyan. Occasionally Harutyun Simonyan and Mher Azatyan participated in exhibitions and discussions though not as members of the group.conceived of the the artist as the engineer of a new world—and promoted the artistic notion of a “pure creativity.”5David Kareyan, “Pure Creativity,” trans. and introduction by Angela Harutyunyan, ARTMargins 2, no. 1 (February 2013): 127–28, https://doi.org/10.1162/ARTM_a_00036. Originally published in Armenian as “Maqur Steghtsagortsutyun,” Garun 8 (1994): 59.This term denotes a conceptual procedure for cleansing artwork of subjective, material, institutional, and other determinations not integral to creativity as well as adopting concrete strategies for making the process of doing so visible through “fixation (inscription)” (documenting everyday objects and gestures), “intervention” (intervening in public spaces or “closed systems”), “inspection” (carrying out explorations and studies of sites, systems, and spheres), and “display” (presenting the results of the former procedures as works of art). At the same time, ACT understood art and the political sphere of the state as separate institutions, each constituted by its own procedural mechanisms, and collectively aimed to demystify both.

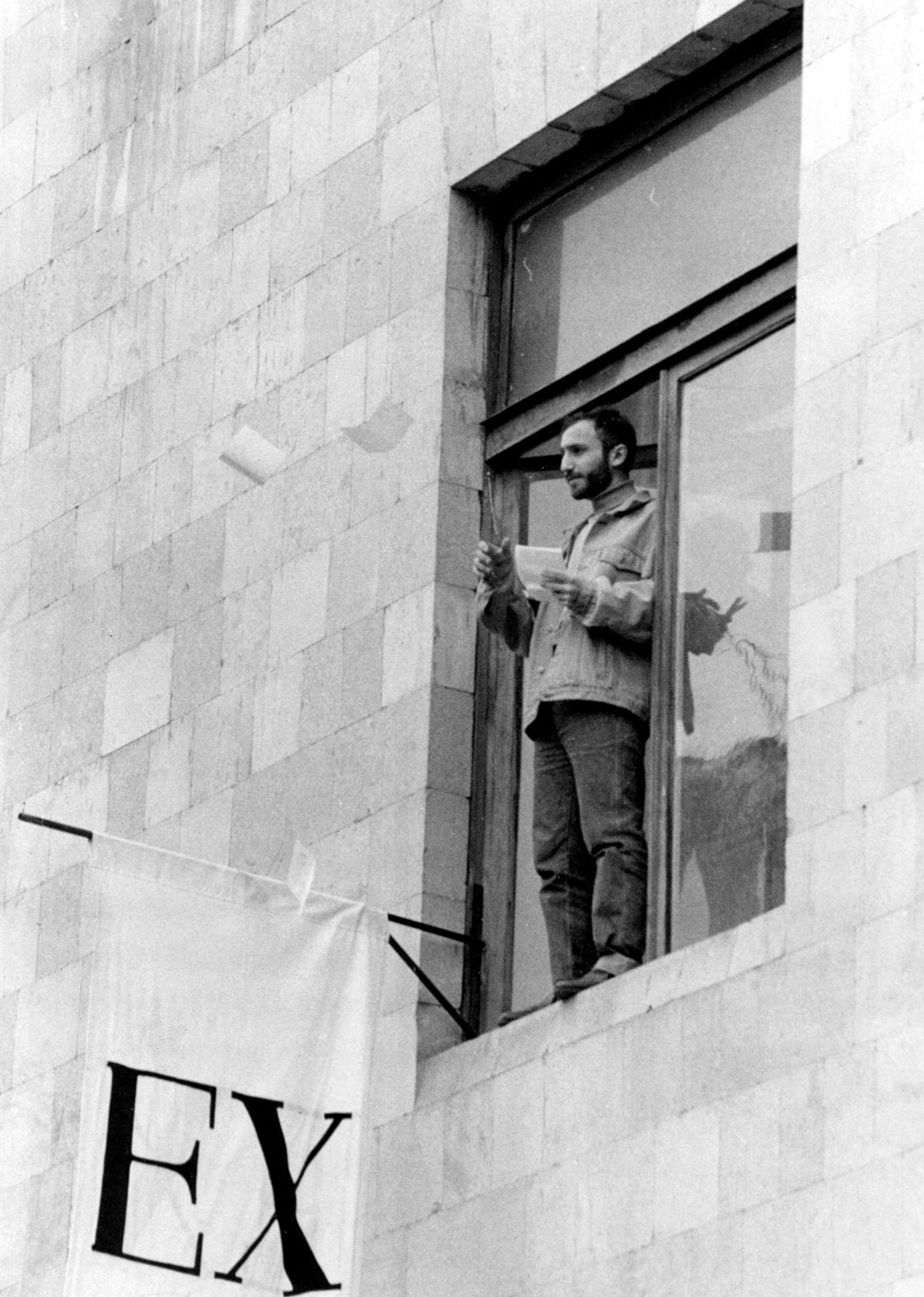

Figure 1. David Kareyan, Art Agitation, action. Exhibition Act, 1995, Ex Voto Gallery. Image courtesy Diana Hakobyan.

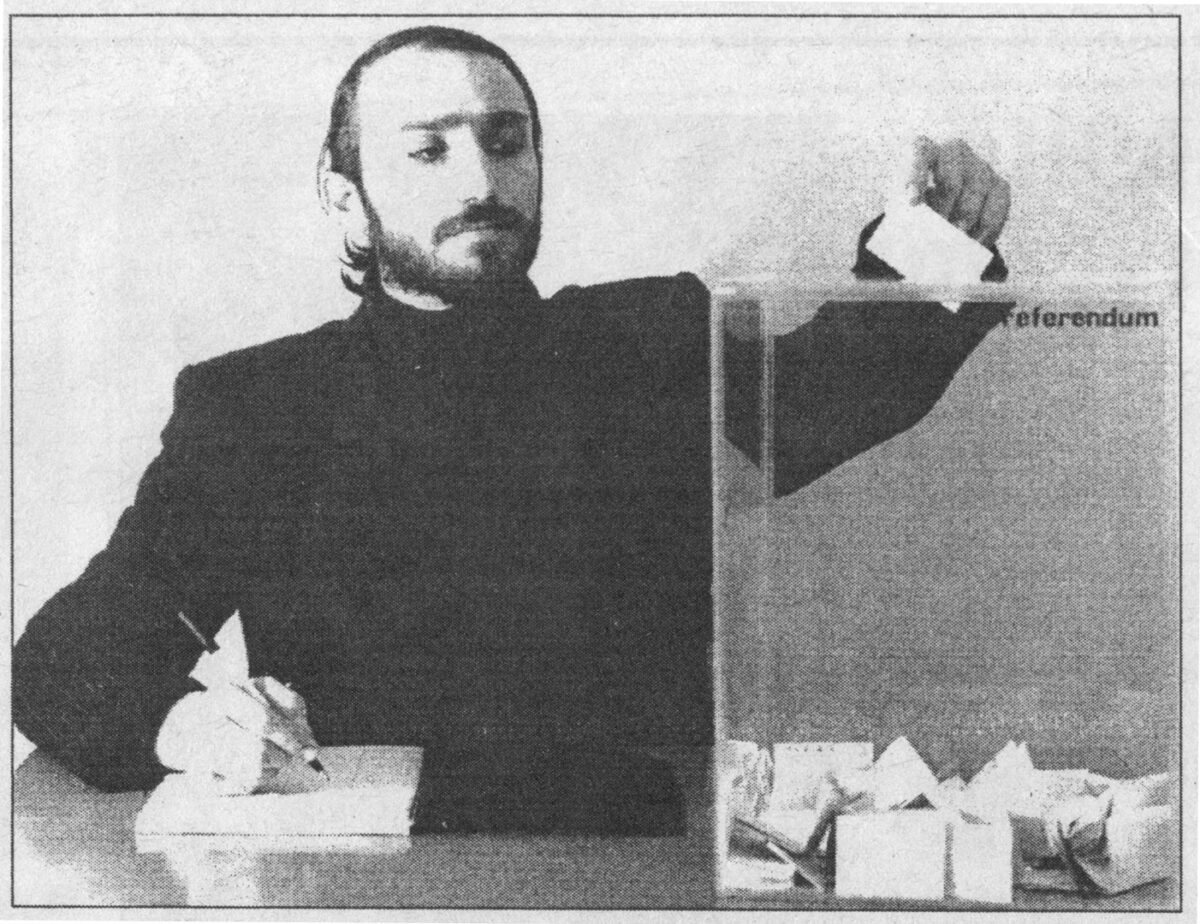

Figure 2. David Kareyan, Art Referendum, action, 1995. Image copied from Grakan monthly, January 2011.

Beginning in 1993, David Kareyan, a key member of the group, was working on a project he called “POLIT-ART,” which involved three strategies borrowed directly from liberal democratic political practices—referendum, demonstration, and agitation—and was realized as collective actions upon the formation of ACT a year later. For the exhibition Act of 1995 in the Ex-Voto Gallery, Kareyan prepared leaflets titled “POLIT-ART,” “Referendum,” “Agitation” and “Demonstration,” and “Actayin hosank” (Actual stream). After using a megaphone to announce these same words through an open window, he threw the leaflets at the audience gathered below (fig. 1). He enacted a “referendum” the same year, in January 1995, at the exhibition of Armenian art held at the Museum Bochum in Germany.6Armenien: Wiederentdeckung einer alten Kulturlandschaft [Armenia: Rediscovery of an Ancient Cultural Landscape], Museum Bochum, January 14–April 17, 1995.Art Referendum incorporated a transparent ballot box labeled “referendum.” An archival photograph reproduced in several newspapers and periodicals shows the artist standing behind the box holding a pen in one hand and casting his vote with the other. The process appears to have been carried out with the utmost seriousness as the artist’s gaze is fixed upon the action he is performing (fig. 2). Viewers were likewise invited to mark and cast a ballot. Finally, in his seminal action Art Demonstration, which he undertook with ACT and other artists as part of Yerevan-Moscow: The Question of the Ark, an exhibition at the Modern Art Museum in Yerevan, Kareyan enacted democratic expression in the form of an artistic action. This much-discussed work is a perfect example of ACT’s identification with and use of political procedures integral to liberal democracy within an artistic form of “pure creativity.”7Vardan Azatyan, “Art Communities, Public Spaces and Collective Actions in Armenian Contemporary Art,” in Art and Theory After Socialism, ed. Mel Jordan and Malcolm Miles (Bristol: Intellect, 2008), 46; and Angela Harutyunyan, “Veraimastavorelov hanrayin volorty: Sahmanadrakan petutyunn u AKT xmki hastatoghakan qaghaqakan geghagitutyuny” [“Rethinking the Public Sphere: Constitutional State and the Affirmative Political Aesthetics of the Group ACT”], Hetq,September 23, 2010), https://hetq.am/hy/article/30593.

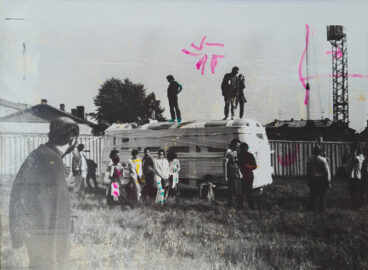

Figure 3. ACT, Art Demonstration, action, 1995. Image courtesy Hrach Armenakyan.

On July 12, 1995, during the opening of Yerevan-Moscow, and exactly one week after the constitutional referendum in Armenia in which the first constitution of the independent state was approved, ACT, together with several other artists, marched along the main avenue in Yerevan (fig. 3).8Yerevan-Moscow: The Question of the Ark, Modern Art Museum, Yerevan, 1995.They covered an artistically defined public space—the area between the statue of early twentieth-century Armenian modernist painter Martiros Saryan (1880–1972), which was also the site of early youth exhibitions in the early 1980s, and the Modern Art Museum. Approximately twenty people carried banners with slogans in Armenian and English, most of which were written in black letters on a white background, calling for “Interventions into Systems,” “World Integration,” “Polit-Art,” “Decentralization,” “Market Relations in Art and Economy,” “Realization,” “No Art,” “Art Referendum,” “New State, Art, Culture,” and “Demythologization”; issuing demands such as “Expel the Information Monsters from Rationality”; proclaiming that “Every Small Mistake Can Result in Big Catastrophes”; and asserting that “Creativity Will Save Humanity.” After reaching the museum, their final destination, the artists hung the banners on the wall as part of Yerevan-Moscow. In this action, the politics of “pure creativity” directly met the pure creativity of politics, as the slogans were both formal interventions in the art institution as well as manifestations of democratic proceduralism in the form of a public demonstration.9Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the “Painterly Real,” 1987–2004 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 148–50.

ACT’s affirmative strategies of overidentification with the political forms of the liberal democratic state through performative actions could be considered unique in contemporary art in Armenia in terms of relating affirmatively to the state and its institutions. As opposed to this, the gestures of ritualistic mimicry by older-generation conceptual artist Grigor Khachatryan (born 1952)—most of which were ironic and often grotesque—related to the mechanisms of the constitution of power and authority. Khachatryan’s work renders political institutions simply as forms through which power and authority are enacted as and through ritual. He performatively assumed “absolute power” through self-mandated award ceremonies (the “Grigor Khachatryan award”), self-aggrandizing declarations (“You are within the radius of the sexual rays of Grigor Khachatryan”), pseudo-institutions (“Center for Planning Accidents”), ceremonial renewing of street plaques ( “Groghneri poghots” or “Writers’ Street”), and “official meetings” (hosting then Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili in the room specially designated for official meetings as part of the Armenian Pavilion at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011). The fictitious persona created by the artist “cannibalizes” the artist’s body as raw material and uses it in repetitive rituals. In the Grigor Khachatryan award ceremony (“tested” in 1974 and held occasionally since 1990),10A photograph from 1974 showing Khachatryan in the arms of artist Vardan Tovmasyan has been restrospectively refunctionalized by the artist as the “testing of the Grigor Khachatryan award.”there are a minimum of three “Grigor Khachatryans”—firstly, the name denotes the artist-author who conceived of the honor; secondly, it appears in the self-referential title of the award; and finally, it is evoked in the trophy itself, which is in the form of the artist’s body—enabling the awardee to literally hold Grigor Khachatryan in their arms (fig. 4). Khachatryan’s actions are not confined to the rituals that constitute officialdom. Indeed, for many years, with humor and irony, he has been rendering everyday mythologies strange (television interventions on Ar TV such as the series City, which he produced with Suren Ter-Grigoryan in the 1990s), deeming national myths banal (Vanna Lich, Gyumri Biennale, 1998), and depicting male friendship as a fantasy of recovering a primordial and infantile state of jouissance (Aratez, with Norayr Ayvazyan, 1993). Khachatryan’s gestures are repetitive and often tautological, a logic that is constitutive of power for its own sake. As sarcastic and antiheroic as his performances might seem, his signature laughter, which often accompanies them, invokes the figure of a joker as truth-teller in the face of power, as a romantic whose heroism is precisely in his antiheroism.

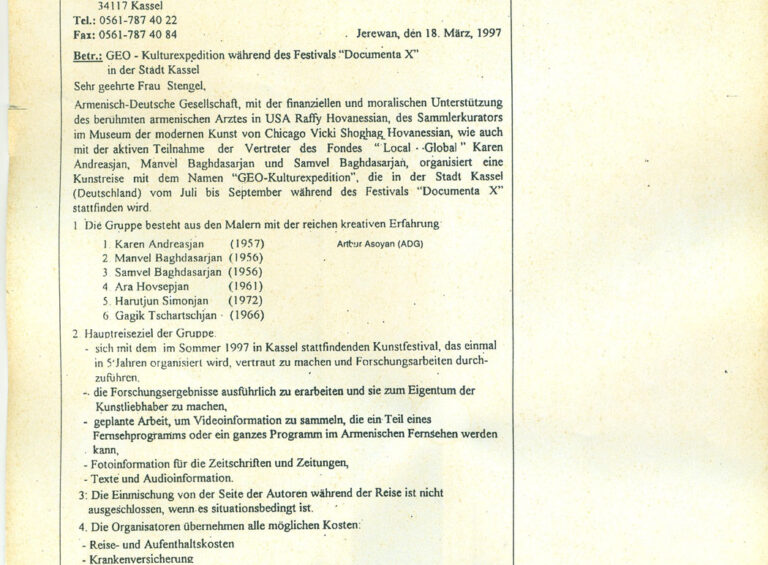

Performative iteration as an intervention into institutional systems, combined with the conception of the artist as an itinerant whose role is to demarcate the boundaries of art’s permissibility characterizes several actions conceived by a loose group of conceptual artists in the mid-1990s. Initially affiliated with the activities of New York–based Iranian Armenian artist Sonia Balassanian (born 1942) in Yerevan since 1993 and ultimately with the foundation of the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA) carried out by Balassanian and her husband, Edward Balassanian, in 1995, artists Karen Andreassian, Ara Hovsepyan, Samvel and Manvel Baghdasaryans, and Gagik Charchyan organized an unofficial intervention in the Tbilisi Biennial of 1996. The Biennial coincided with the artists’ schism with Balassanian and became a tacit protest against ACCEA, which organized the official Armenian Pavilion.11Nare Sahakyan, “Drvagner 1990—akanneri hayastanyan konceptual arvesti. Haraberutyunner ev dirqoroshumner” [“Passages in Armenian Conceptual Art of the 1990s: Relations and Positions”] (graduation project, Institute of Contemporary Art, Yerevan, 2014).Inspired by the rhetorical question posed by scandalous Russian artist Alexander Brener: “Why haven’t I been invited to this exhibition?” (“Почему меня не взяли на эту выставку?”), artists went to the biennial with so-called geopolitical cards (also the title of the intervention), carrying their own name tags along with those of famous artists and acting as representatives of a fictitious foundation called “Local Global.” On the one hand, the intervention voiced a locally articulated discontent with ACCEA’s collaboration with artists other than the group through a construction of a fictitious and situational counter-institution;12Sahakyan, “Drvagner 1990.”on the other, it brought to the surface a key problematic for post-Soviet Armenian artists—that of the desire to participate in a global art world through a language and means characterizing conceptual art.13Vardan Jaloyan, “Turismy ev nuynakanutyun” [“Tourism and Identification”], In Vitro, no. 1 (1998): 30.It is especially the latter aspect that informed their expedition the next year to the German city of Kassel.

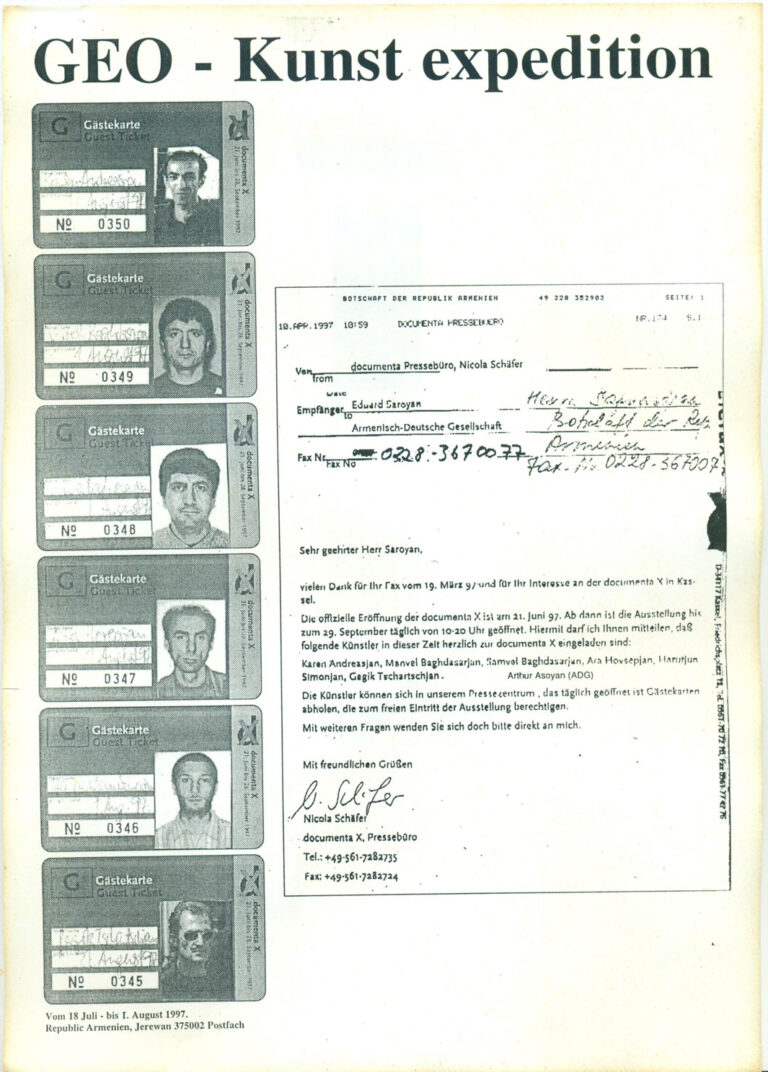

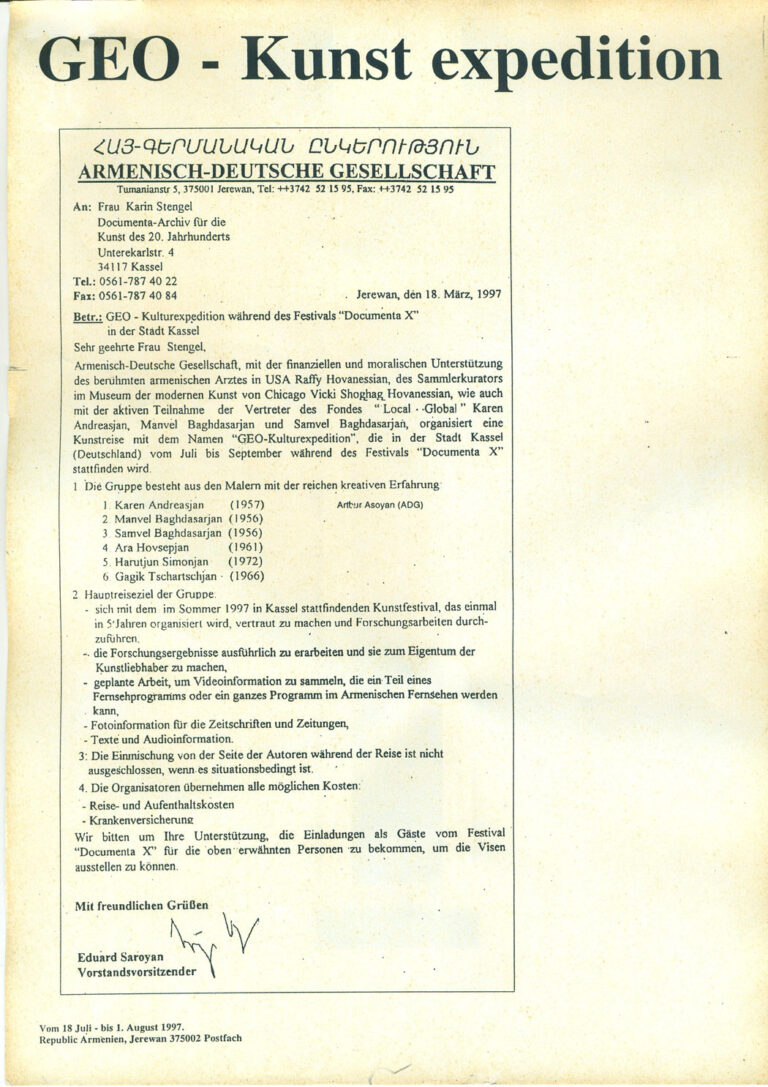

In 1997, the same group of artists—a collective that was situational rather than long-standing or cohesive—organized an unofficial intervention in the authoritative documenta X curated by Catherine David in Kassel (fig. 5). GEO-Kunst Expedition documented the artists’ journey from Yerevan to the exhibition. Once in Kassel, the group created a pseudo-official letterhead with the logo of the documenta, thus hijacking the institutional trademark. The artists posted copies of this fake stationery across the city with a call for the public to post messages or artworks on them. They conceived this intervention as providing a space on the stationery of the prestigious art event to post a message or an artwork, so that anyone could claim participation in the documenta. The letterhead thus acted as a sort of parasitic institution created by the uninvited guests. Thus, the Armenian artists were inserting themselves into the global contemporary art context that had allegedly bypassed them.14Vardan Jaloyan, text of the exhibition catalogue GEO-Kunst Expedition, In Vitro, no. 2 (1998): 42.This self-insertion was understood quite literally as the artists made sure to be photographed with David and to have the curator perform as an “artist” in the unofficial documenta by having her sign their fake letterhead. For a moment, the unofficial artists and official curator changed places.

All the examples discussed here point to a shift in late Soviet period discourse, aesthetics, and political attitude in performative artistic practices in Armenia. If the unofficial artists of the perestroika avant-garde conceived of their actions in terms of resistance toward official institutions, the artists in the early years of independence positioned themselves affirmatively in relation to the newly evolving state and its cultural discourses. They often did so through actions, performances, and artistic gestures that mimicked state rituals and forms of democratic participation.

The research for this three-part article was commissioned by ARé Cultural Foundation in 2022. Some parts are informed by earlier research conducted for my monograph. See Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the “Painterly Real,” 1987–2004 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017).

Editors’ note: Read the Introduction and Part I of this series here, and Part III here.

Author’s note: The research for this three-part article was commissioned by ARé Cultural Foundation in 2022. Some parts are informed by earlier research conducted for my monograph. See Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the “Painterly Real,” 1987–2004 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017).

- 1“Art actions” is the term preferred by the young artists entering the scene in the 1990s.

- 2Official exhibitions were held in 1995 in Moscow’s Central House of Artists, in Bochum’s Galerie Bochumer Kulturrat, and in the Pharos Trust in Nicosia, Cyprus.The year also marks the first time the Republic of Armenia took part in the Venice Biennale; the Armenian Pavilion, which featured Samvel Baghdasarian and Karen Andreassian, was organized by the Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art.

- 3After the collapse of the USSR and throughout the construction of a new democratic state, artists largely embraced the official cultural politics. Hence, a certain crisis of resistance emerged in which it was no longer possible for self-identifyng avant-garde artists to maintain the ethos of negation of the dominant social order.

- 4Naira Aharonyan, Hrach Armenakyan, Vahram Aghasyan, Narine Aramyan, Narek Avetisyan, Diana Hakobyan, Samvel Hovhannisyan, David Kareyan, Rusanna Nalbandyan, and Arthur Vardanyan. Occasionally Harutyun Simonyan and Mher Azatyan participated in exhibitions and discussions though not as members of the group.

- 5David Kareyan, “Pure Creativity,” trans. and introduction by Angela Harutyunyan, ARTMargins 2, no. 1 (February 2013): 127–28, https://doi.org/10.1162/ARTM_a_00036. Originally published in Armenian as “Maqur Steghtsagortsutyun,” Garun 8 (1994): 59.

- 6Armenien: Wiederentdeckung einer alten Kulturlandschaft [Armenia: Rediscovery of an Ancient Cultural Landscape], Museum Bochum, January 14–April 17, 1995.

- 7Vardan Azatyan, “Art Communities, Public Spaces and Collective Actions in Armenian Contemporary Art,” in Art and Theory After Socialism, ed. Mel Jordan and Malcolm Miles (Bristol: Intellect, 2008), 46; and Angela Harutyunyan, “Veraimastavorelov hanrayin volorty: Sahmanadrakan petutyunn u AKT xmki hastatoghakan qaghaqakan geghagitutyuny” [“Rethinking the Public Sphere: Constitutional State and the Affirmative Political Aesthetics of the Group ACT”], Hetq,September 23, 2010), https://hetq.am/hy/article/30593

- 8Yerevan-Moscow: The Question of the Ark, Modern Art Museum, Yerevan, 1995.

- 9Angela Harutyunyan, Political Aesthetics of the Armenian Avant-Garde: The Journey of the “Painterly Real,” 1987–2004 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2017), 148–50.

- 10A photograph from 1974 showing Khachatryan in the arms of artist Vardan Tovmasyan has been restrospectively refunctionalized by the artist as the “testing of the Grigor Khachatryan award.”

- 11Nare Sahakyan, “Drvagner 1990—akanneri hayastanyan konceptual arvesti. Haraberutyunner ev dirqoroshumner” [“Passages in Armenian Conceptual Art of the 1990s: Relations and Positions”] (graduation project, Institute of Contemporary Art, Yerevan, 2014).

- 12Sahakyan, “Drvagner 1990.”

- 13Vardan Jaloyan, “Turismy ev nuynakanutyun” [“Tourism and Identification”], In Vitro, no. 1 (1998): 30.

- 14Vardan Jaloyan, text of the exhibition catalogue GEO-Kunst Expedition, In Vitro, no. 2 (1998): 42.