Curator Luis Pérez-Oramas considers the roots of the classicizing and modernist impulses in the work of Joaquín Torres-García. The essay examines a driving paradox of the artist’s work–the will to be modern while working against the grain of modernity–following episodes in his life, writings, and works. This is the first of three parts.

In the last part of Faust, the great poet Goethe said that reality is only a symbol. And we well know that form is only a mask. —Joaquín Torres-García, La Raison, 1932

L’equilibri ès possible/però la inquietud/sempre ès present . . . silenci i llum/cercle&carré/inesgotables constructions . . . (Equilibrium is possible/however unrest/is always present . . . Silence and light/cercle&carré/inexhaustible constructions . . .) —Albert Ràfols-Casamada, Policromia o La galeria dels mirals, 1999

Joaquín Torres-García had reached maturity and was in Paris, resolutely coming to terms with what he had already become by chance:1I refer to the last pages—in fact the last page—of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception, which includes a description of freedom as the ability to come to terms with the present, and of the need for a certain gift to be able to make something productive out of life’s choices. Merleau-Ponty writes, “It is by being what I am at present, without any restrictions and without holding anything back, that I have a chance at progressing; it is by living my time that I can understand other times; it is by plunging into the present and into the world, by resolutely taking up what I am by chance, . . . that I can go farther.” Italics added. Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 1945 (Eng. trans. New York: Routledge, 2012). a foreigner, strange and a stranger, an artist who had traversed—as one might traverse rough terrain—the aspirations and delusions of the modern avant-gardes.2Here I refer to the philological connection in Spanish between the strange (lo extraño) and the foreigner or stranger (lo extranjero), between what comes from outside and what is alien to us. See Pierre Fédida, Le Site de l’étranger (Paris: PUF, 1995), p. 156. It was 1930; Adolf Hitler would soon come to power in Germany; in France, the moderate conservative premier André Tardieu governed a country wracked by economic recession, the Wall Street crash having dragged down economies throughout the West. Six years later Spain would enter a devastating civil war, drowning in a bitter sea of blood—prelude to a war that would be a watershed moment in European history, enshrining the twentieth century as one of humanity’s most violent.

The origins of modernity, and of modern art, drew from the century’s sea of blood. No one exists outside of history, but the machine-loving cries of the Futurists, the epicurean cynicism of Dada, the production-oriented heroics of the Constructivists, the moral neutrality of the devotees of pure form, the fetish or nostalgia for the Golden Age—all these prepared the ground for that tragic era, and all drew from the same well of anguish.3See José Bergamín, El pozo de la angustia. Burla y pasión del hombre invisible (Mexico: Editorial Séneca, 1941), p. 12. Given the scale of the century’s tragedies, these artists’ aspirations to begin the world anew through new form can also, in hindsight, be read as delusions.

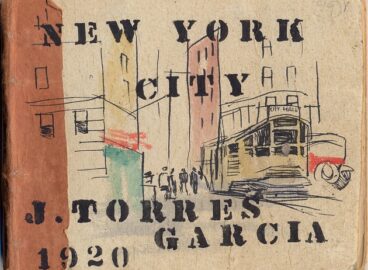

This was the world in which Torres found himself on arriving in Paris in 1926, after brief stays in the modest rural towns of Fiesole and Livorno, Italy, and Villefranche-sur-Mer, France. On leaving New York for Europe two years earlier, at the age of fifty, he still had not yet found his “definitive language” as an artist.4For the Torres scholar Juan Fló, this would not come until around 1929. See Fló, “Torres García—Nueva York,” in J. Torres-García: New York (Montevideo: Fundación Torres-García and Casa Editorial HUM, 2007), p. 23. All the evidence suggests that as this tragic century was reaching the end of its first quarter, he had so far lived intensely as someone who had learned to resist it—perhaps because his intelligence had been shaped by his anachronistic training in medieval scholasticism, perhaps because he had an intuitive distrust of the new.5In 1893, as a young artist in Barcelona, Torres entered the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc, an artists’ group led by the Catholic bishop and philosopher Josep Torras i Bages (1846–1916), a founder of modern, Christian-inspired Catalan nationalism.

Torres had reached maturity, then, and amid the dying gasps of the modern avant-gardes, his age gave him a certain spiritual distance, allowed him certain liberties, set him apart from the avant-garde passion for militant confrontation. This mood informed a sort of cursory theoretical manifesto he wrote in that year of 1930 on what he called “construction.” The manifesto, Vouloir construire (Will to construct), ran in the first issue of Cercle et Carré (the journal of the movement of the same name that he had helped to found but would soon leave), following a long text by Michel Seuphor, “full of twists and turns and uselessly lengthy,”6Michel Seuphor, Le Style et le cri. Quatorze essais sur l’art de ce siècle (Paris: Seuil, 1965), p. 116. according to its own author. Torres wrote:

“The more the person drawing has a spirit of synthesis, the more of a constructed image he will give us. The drawings of all primitive peoples—black, Aztec, etc., as well as Egyptian, Chaldean, etc.—are great examples. This spirit of synthesis, I believe, is what leads to the construction of the whole painting, and of sculpture, and to the determining of the proportions of architecture. This spirit alone allows the work to be seen in its totality as a single order, a unity. What wonders this rule has created across the ages! Why has it been overlooked?”

And he added: “This rule is an anonymous thing; it belongs to no one.”7Joaquín Torres-García, “Vouloir construiré,” Cercle et Carré no. 1 (March 15, 1930):2.

In Vouloir construire, without denying the possibility of turning to “the pure ideas of understanding” in the search for order, Torres-García argued for intuition as the tool with which to define visual art.8Ibid., p. 2. For him, the academic chapter of art that had begun in the Renaissance, with its mathematical system of perspective, was only a brief interruption in the primacy of that anonymous intuitive rule. It was this rule, belonging to no one in particular, that had allowed for the creation of the array of symbolic and artistic forms known up to that moment.

Without declaring itself as such, Vouloir construire was a participant in a trend toward the recovery of memory. It was a spiritual contemporary of the period’s complex projects of Mnemosyne, from Franz Boas to Aby Warburg, from Carl Einstein to Carl Jung, from Walter Benjamin to Ernst Cassirer, all working under the sign of a heterogeneous archaeology of historical forms and of their anachronistic recurrence. This was a quiet movement, running against the grain of a certain messianic modern devotion to progress—that is, against the grain of the avant-gardes. To understand the legacy of Torres-García—“that right-minded and highly skilled artist who, like [Paul] Klee . . . was always untimely, whether behind the times or ahead of his time”9Fló, J. Torres-García: New York, pp. 37–38.

—we must look at the question at the end of his article in Cercle et Carré: “This rule is an anonymous thing; it belongs to no one. Everyone can use it in their own way; it should be the true road of any honest man. But if it has been used throughout the ages, how might it be used in a modern way?”10Torres-García, “Vouloir construiré,” p. 3.

As Torres reclaimed an age-old anonymous rule, then—a universal rule, since everyone could use it in their own way—he also interrogated its modern form, its contemporary texture, its place in the present. Unlike other modern Latin American artists, such as Armando Reverón, he made clear his will to be modern. Yet he worked against the grain of modernity, always looking for schematic, primal images. That paradox is the subject of this essay, but for now, Torres’s question about the modern use of the anonymous rule will suffice to inscribe his name in the vast archives of the will to be modern and of the modern will.

Born in 1874 in Montevideo, Uruguay, Torres-García was five years younger than Henri Matisse, two years younger than Piet Mondrian. He was seven years older than Pablo Picasso, five years older than both Klee and Kazimir Malevich, seven years older than Theo van Doesburg, a decade older than Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. He was almost a contemporary of his fellow Uruguayan José Enrique Rodó (born in 1871), whose anti-utilitarian Pan-American ideals may be located in relation to his.11See the letters from Torres-García to José Enrique Rodó published in “De Maestro a maestro: las cartas de Torres a Rodó,” El País (Montevideo), August 26, 1974, p. 5. Torres-García’s thinking on the visual made as large a contribution to shaping the cultural thought of Latin America as did the writings of the Nicaraguan Rubén Darío (born 1867), the Mexicans José Vasconcelos (born 1882) and Alfonso Reyes (born 1889), and the Peruvian José Carlos Mariátegui (born 1894), all of them younger than he.

The son of a Catalan immigrant father and a Uruguayan mother, Torres was European in America and South American in Europe, participating simultaneously in two modernities that stopped communicating at the start of the twentieth century, owing perhaps to the same unease, the same tragedies, evoked at the beginning of this essay. One of these modernities was that of the great urban metropolis of the early century—cities like Barcelona, New York, and Paris, to name only those where Torres lived. The second arose out of an impulse to be modern in the societies of Hispanic America, societies lucky enough to be spared the carnage of World War I but for that reason marked by a double temporality, combining a will to be modern with foundational feudal anachronisms that in some Latin American nations persist to this day. And although the Eastern Republic of Uruguay is one of the smallest countries in South America, it produced great protagonists of that will to be modern, figures of continent-wide impact. In the visual arts alone, in addition to Rodó, three of South America’s most notable early-modern artists were born in Uruguay in more or less the same period as Torres: Pedro Figari (1861), Carlos Federico Sáez (1878), and Rafael Barradas (1890), whose friendship with Torres was central to what Juan Fló has called the latter artist’s “first conversion” to the modern, around 1917.12Fló, J. Torres-García: New York, p. 23.

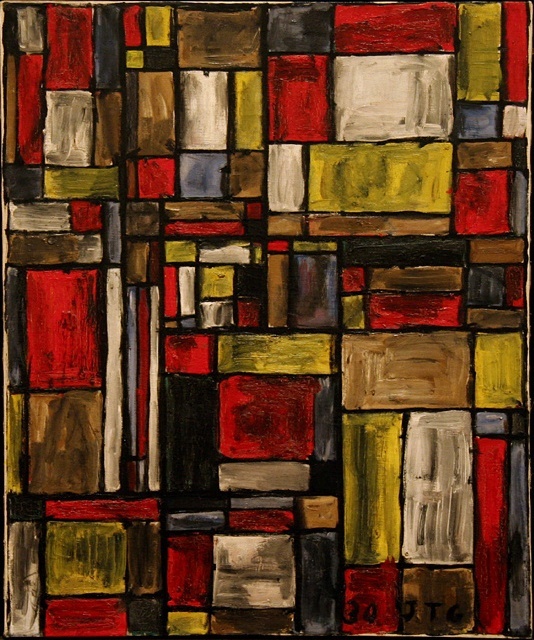

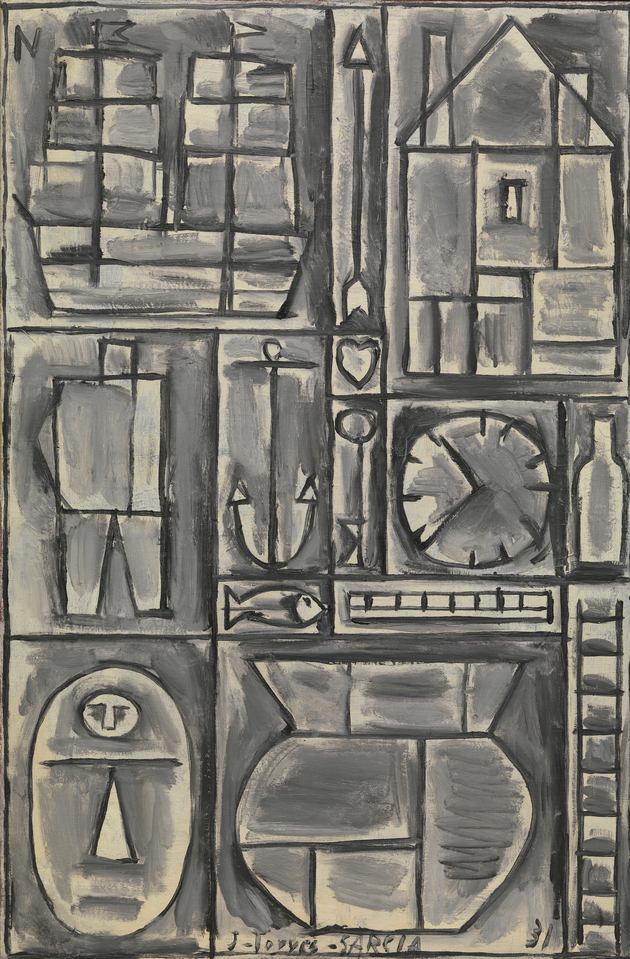

Perhaps Torres’s work as a painter was a response to the question posed by Torres the theorist in the 1930 article that initiated his brief tour through the modernity of Paris. By then, he had already produced a significant body of work showing signs of a schematic impulse—an impulse toward turning a given form into a primal representational matrix, a matrix conceived purely in the imagination rather than in the form’s iconographic history, yet implying a primeval version of it. A concern for the synthetic—for adhering to the essential, unenhanced elements of a concrete form—generated a taste for coarse, even crude resolutions: a rough texture, a dark palette, a sprezzatura informed by the spirit of geometry but not of refinement. Among these works, a few paintings and the highly plastic works in wood, often rustic in construction, foreshadowed what would come to be Torres’s definitive language, the “primitive” pictographic signature that would become a highlight of his work after the immensely productive year of 1931.

The Torres who staked a claim on a universal intuition—who believed in an “anonymous rule,” a spirit of synthesis that he saw behind the symbolic creations of tribal peoples—was both Arcadian and modern, a modern artist who saw, or aspired to, a “primitive” modernity. To get there, and to reconcile that modern teleology with his personal archaeology of forms, Torres had to leave behind his academic baggage, the intricate symbolism that he had drawn on to emerge as an artist—and a central one—in early-twentieth-century Catalonia. He had to delve into and dismantle his own subject matter, finding beneath its more easily available representations a basso continuo simultaneously ancient and modern, Arcadian and futurist. This subject matter had nothing to do with narrative or with psychological characters; it related simply to the visual structures on which it was based and that it simultaneously highlighted.

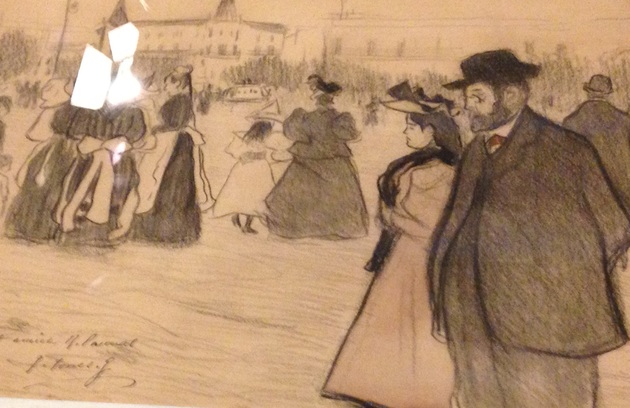

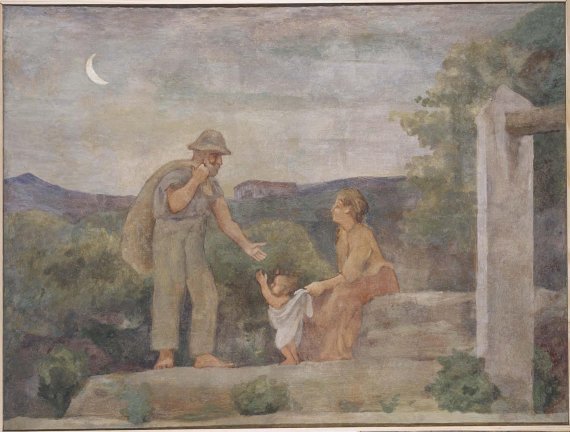

The first test Torres faced, in Barcelona at the dawn of the twentieth century, entailed a choice between modernism and the wild, edenic Noucentisme, an early-twentieth-century Catalan art movement that opposed the then fashionable trend of Art Nouveau with a call for Arcadian simplicity, expressed through visions of a rustic Mediterranean Golden Age. It should be said that “modernism” is understood here not only as it manifested in Catalonia but in the Latin American sense that embraced the neo-Parnassian poetry of Darío or of the Uruguayan Julio Herrera y Reissig. In the visual arts, “modernism” also entailed a decadent fin de siècle aesthetic in which various figures stand out: the Baudelairean “man of the crowd” or flaneur, devoted to “the outward show of life as it appears in the capitals of the civilized world”;13“La pompe de la vie, telle qu’elle s’offre dans les grandes capitales du monde civilisé.” Charles Baudelaire, “Le Peintre de la vie moderne,” 1863, in Ecrits esthétiques (Paris: Union Générale d’Editions, 1986), p. 385. Constantin Guys, subject of Baudelaire’s essay “The Painter of Modern Life”; Théophile Steinlen, an acknowledged influence on Torres; even the young Pablo Picasso—not to mention Edouard Manet or Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.14See Torres-García, Historia de mi vida (Montevideo: Asociación de Arte Constructivo, 1939), p. 108. In Barcelona at the turn of the century, the young Torres was certainly a painter of modern life. He equally certainly abandoned this commitment to the comedy of the world quite early on, anticlimactically changing direction in favor of a Noucentista siren song and working for a time on visualizing the Mediterranean Arcadia imagined by the political and cultural leaders of Catalonia’s nascent nationalism. His pictures became scenes of maternity, an eternal nature, the landscape of the Levante—the morning of a serene ideal world of fruits, fountains, and luminous calm, accompanied by the ages of man.15See Narcís Comadira, “Torres-García en la configuración del Noucentisme,” in Emmanuel Guigon et al., Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949) (Barcelona: Museu Picasso, Institut de Cultura de Barcelona, 2003), p. 35, and Tomás Llorens, “Torres-García: a les seves cruïlles,” in Torres-García: a les seves cruïlles (Barcelona: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2011), p. 12.

There is still some confusion about Torres’s influences and affinities at this early moment. As he adopted Arcadian imagery, he cast off the baggage of Symbolism. His ideal gardens do not belong to the pompier repertoire in the style of Thomas Couture, nor can they be entirely attributed to the influence of Puvis de Chavannes, despite resemblances in iconography and Torres’s own recognition that Puvis had nourished him for a time. But the artist himself could not have been clearer in his autobiography: “Leaving behind more superficial ideas, after basing my work on Puvis de Chavannes, I had finally taken Greek art as my model,” a model coinciding with the anti-Castilian political ideals of Catalan thinkers such as Eugeni d’Ors, Enric Prat de la Riba, and Josep Torras i Bagès.16Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 135. This may have been the only time in Torres’s life when his aesthetic ideas corresponded to a political context, an accord that translated into the first and largest public commission of his career: frescoes for the Saló de Sant Jordi, the chapel in Barcelona’s Palau de la Generalitat de Catalunya, the seat of Catalan political power since the Middle Ages.

The story of this commission, told in part by Torres himself in his autobiography, would become the story of his first disappointment in Europe, certainly a factor in his later move to New York.17Ibid., p. 173 ff. The frescoes demonstrate his interest in Mediterranean and Arcadian iconography. Before painting them he traveled to Italy to see Roman and Renaissance murals, identifying with those artists and particularly with Giotto. He spent six years planning the works, developing allegories on the themes of La Catalunya eterna (The eternal Catalonia, 1912), L’edat d’or de la humanitat (Humanity’s golden age, 1915), Les Arts (The arts, 1916), Lo temporal no és més que símbol (The temporal is no more than symbol, 1916), and La Catalunya industrial (The industrial Catalonia; unfinished). The sketch for this last fresco suggests that Torres intended to establish an opposition between antiquity and the present, between an ideal and a modern imaginary, though it is impossible to confirm this without further evidence.18A sketch suggests that Torres may have initially planned to show three levels of content in each fresco: symbolic in the foreground, allegorical in the framing figures, and historical in the central scene. Yet given the differences between this plan and the completed frescoes, he clearly made substantial modifications. See Torres-García, Mapa iconográfico Sant Jordí, unpublished, accession no. 960087, box 1, folder 1, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. What is clear is that the unveiling of the first fresco was accompanied by scandal: an important sector of the Catalan cultural world denounced its “overly systematic” composition—a charge made even by d’Ors, though he supported Torres anyway—and even a quality that “we would almost call infantile.”19See Joan Sureda, Torres-García. Pasión clásica (Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 1998), p. 168. Through the support of Prat de la Riba, first president of the Mancomunitat de Catalunya (Commonwealth of Catalonia), Torres was able to complete three more frescoes, but after that political leader’s death, in 1917, the contract was canceled. Even then, opposition to the murals continued, and in 1926—with the artist out of the country and the dictator Miguel Primo de Ribera ruling Spain—his “Greek” images were censured and eventually covered over with other canvases. It remains surprising that the initial pretext for their rejection was their stripped-down appearance—their antisensuality, as Fló puts it; their flatness, their “muted tonality.”20See Fló, “Los frescos del Salón de San Jordí,” in Exposición de los Bocetos y Dibujos de los Frescos del Salón de San Jorge en la Diputación de Barcelona (Montevideo: Fundación Torres-García, 1974), p. 4.

Torres’s interest in a Noucentista Arcadia—his first move against the grain of his times—can be seen as a first sign of an antimodern spirit. Tomás Llorens, for example, has argued that it marked the emergence of the Torres who understood “modernity as archaism.”21Llorens, “Torres-García: a les seves cruïlles,” p. 22. But a judgment based on the works’ iconography may mislead: a fin de siècle (modernist) appearance and an Arcadian (Noucentista) scene are not necessarily opposed. Nor do Torres’s iconographic choices settle the question of his approach to the art of his time. In fact his schematic, near-monumental treatment of some of the classical figures in the Sant Jordi frescoes, particularly in the last one he completed, Lo temporal no és més que símbol—a work to which we will return—is absolutely modern and can be linked to a number of artists involved in classical impulses at the time, from Picasso to Mario Sironi and Giorgio de Chirico, from Carlo Carrà to Georges Braque. Perhaps Torres’s Noucentista foray signaled only that he was, from the start, an antimodern modernist—a scholastic modernist, as James Joyce was in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), from the same period, and as T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Jean Cocteau, Max Jacob, Igor Stravinsky, Jacques Maritain, and Benedetto Croce would at some points be as well.

This antimodern modernity—this reserve of antimodernism that runs deep in some of the period’s best-known art and literature—was a crucial part of the modern project itself. Maturing within Torres in the early twentieth century were some of the same classical images, the same “Saturnian motifs,” that would emerge in the interwar period’s return to classicism, where they were charged with a “disturbing strangeness.”22See Jean Clair, Malinconia. Motifs saturniens dans l’art de l’entre-deux-guerres (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), p. 59 ff. Perhaps Torres’s modernity was based on a concern with primary sources—sources of culture, certainly (hence his affiliation with Catalan Arcadianism), but also of creative intuition passed through his philosophical, classical, and scholastic education. But “classical” is too narrow a term: the coexistence of these sources, simultaneously spiritual and material, in Torres is what makes him a protean modern artist, a modern figure who was practicing the lessons of Baudelaire perhaps without having read them. I am thinking of the Baudelaire who wanted a beauty combined both of the unchanging and eternal—whose depths are hardly visible—and of the circumstantial and relative, a beauty embracing “period, style, spirit, passion”23Baudelaire, “Le Peintre de la vie moderne,” p. 362. without forgetting Thomas Aquinas’s idea that art imitates nature in its manner of operation, not in its appearance.24“Ars imitatur naturam in sua operatione.” See Umberto Eco, The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1988), p. 165.

The “Greek” chapter of early modernity, of which Torres’s version of Noucentisme was a part, may not have received the attention it deserves. The Torres who, in 1907, joined the faculty of Mont d’Or, a school, inspired by the ideas of John Dewey, that practiced the Montessori method of “teaching through delight”; the Torres who took on the key public commission given to any Noucentista artist, for the frescoes in the Saló de Sant Jordi; the Torres who, in 1914, conceived and built Mon Repòs, his house outside Barcelona—“half classical temple, half Catalan cottage,”25Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 163. as he described it—this Torres shared an aesthetic spirit that was visible, with local accents, from Moscow to Venice, from Berlin to London: a construction of community around a shared fascination for “Greekness.” As Guillermo de Osma writes:

“The nineteenth-century sense of morality was ebbing and Greekness went beyond the fields of painting and art into social practices. Members of society threw Greek parties and dressed in Greek style, and not only was Greek love accepted—after the cruel punishment inflicted on [Oscar] Wilde—it was practiced by many intellectuals, artists, and patrons and leaders of fashion, both men and women. . . . Greece was an obligatory pilgrimage for artists and poets. [Léon] Bakst was profoundly impressed when he toured there around 1905, and his designs for the Greek ballets he produced for the Ballets Russes are permeated with those memories. Isadora Duncan’s new dance revived the emotional and Dionysian meaning of classical dance.”26Guillermo de Osma, Fortuny, proust y los Ballets Rusos (Barcelona: Elba, 2010), pp. 47–48.

Catalan Noucentisme was one manifestation of this passion for “Greek style” in the modern century. To suggest the extent of that passion, not to mention its quite innovative modernity, we might cite figures ranging from Mariano Fortuny—whose “Knossos” veil and “Delphos” gown, which revealed the natural form of the female body, were probably worn by Torres’s wife, Manolita, during what may have been her husband’s single moment of public success—to the Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie, and Picasso of Parade.27Torres attended the production of Parade at the Liceu de Barcelona in 1917, and published an article defending it in November of that year. See Torres-García, “Un ballet rus de picasso: Parade,” La Revista (Barcelona) no. 53 (December 1, 1917):428. Warburg’s essays “Dürer and Italian Antiquity” (1905), “The Gods of Antiquity and the Early Renaissance in Southern and Northern Europe” (1908), and “The Emergence of the Antique as a Stylistic Ideal in Early Renaissance Painting” (1914) are further, radical iterations of this impulse toward antiquity in modern thinking. Torres-García followed the same impulse during these years, in serene, sunny images that left the nineteenth century behind and began the laborious process of entering twentieth-century modernity.

This is the first section of the text, excerpted from Luis Pérez-Oramas’s essay, “The Anonymous Rule: Joaquín Torres-García, the Schematic Impulse, and Arcadian Modernity,” in the exhibition catalog Joaquín Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern available in the MoMA Design Store and online. Read the remaining two sections here: Part 2 and Part 3.

- 1I refer to the last pages—in fact the last page—of Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception, which includes a description of freedom as the ability to come to terms with the present, and of the need for a certain gift to be able to make something productive out of life’s choices. Merleau-Ponty writes, “It is by being what I am at present, without any restrictions and without holding anything back, that I have a chance at progressing; it is by living my time that I can understand other times; it is by plunging into the present and into the world, by resolutely taking up what I am by chance, . . . that I can go farther.” Italics added. Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 1945 (Eng. trans. New York: Routledge, 2012).

- 2Here I refer to the philological connection in Spanish between the strange (lo extraño) and the foreigner or stranger (lo extranjero), between what comes from outside and what is alien to us. See Pierre Fédida, Le Site de l’étranger (Paris: PUF, 1995), p. 156.

- 3See José Bergamín, El pozo de la angustia. Burla y pasión del hombre invisible (Mexico: Editorial Séneca, 1941), p. 12.

- 4For the Torres scholar Juan Fló, this would not come until around 1929. See Fló, “Torres García—Nueva York,” in J. Torres-García: New York (Montevideo: Fundación Torres-García and Casa Editorial HUM, 2007), p. 23.

- 5In 1893, as a young artist in Barcelona, Torres entered the Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc, an artists’ group led by the Catholic bishop and philosopher Josep Torras i Bages (1846–1916), a founder of modern, Christian-inspired Catalan nationalism.

- 6Michel Seuphor, Le Style et le cri. Quatorze essais sur l’art de ce siècle (Paris: Seuil, 1965), p. 116.

- 7Joaquín Torres-García, “Vouloir construiré,” Cercle et Carré no. 1 (March 15, 1930):2.

- 8Ibid., p. 2.

- 9Fló, J. Torres-García: New York, pp. 37–38.

- 10Torres-García, “Vouloir construiré,” p. 3.

- 11See the letters from Torres-García to José Enrique Rodó published in “De Maestro a maestro: las cartas de Torres a Rodó,” El País (Montevideo), August 26, 1974, p. 5.

- 12Fló, J. Torres-García: New York, p. 23.

- 13“La pompe de la vie, telle qu’elle s’offre dans les grandes capitales du monde civilisé.” Charles Baudelaire, “Le Peintre de la vie moderne,” 1863, in Ecrits esthétiques (Paris: Union Générale d’Editions, 1986), p. 385.

- 14See Torres-García, Historia de mi vida (Montevideo: Asociación de Arte Constructivo, 1939), p. 108.

- 15See Narcís Comadira, “Torres-García en la configuración del Noucentisme,” in Emmanuel Guigon et al., Joaquín Torres-García (1874–1949) (Barcelona: Museu Picasso, Institut de Cultura de Barcelona, 2003), p. 35, and Tomás Llorens, “Torres-García: a les seves cruïlles,” in Torres-García: a les seves cruïlles (Barcelona: Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 2011), p. 12.

- 16Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 135.

- 17Ibid., p. 173 ff.

- 18A sketch suggests that Torres may have initially planned to show three levels of content in each fresco: symbolic in the foreground, allegorical in the framing figures, and historical in the central scene. Yet given the differences between this plan and the completed frescoes, he clearly made substantial modifications. See Torres-García, Mapa iconográfico Sant Jordí, unpublished, accession no. 960087, box 1, folder 1, Research Library, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

- 19See Joan Sureda, Torres-García. Pasión clásica (Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 1998), p. 168.

- 20See Fló, “Los frescos del Salón de San Jordí,” in Exposición de los Bocetos y Dibujos de los Frescos del Salón de San Jorge en la Diputación de Barcelona (Montevideo: Fundación Torres-García, 1974), p. 4.

- 21Llorens, “Torres-García: a les seves cruïlles,” p. 22.

- 22See Jean Clair, Malinconia. Motifs saturniens dans l’art de l’entre-deux-guerres (Paris: Gallimard, 1996), p. 59 ff.

- 23Baudelaire, “Le Peintre de la vie moderne,” p. 362.

- 24“Ars imitatur naturam in sua operatione.” See Umberto Eco, The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1988), p. 165.

- 25Torres-García, Historia de mi vida, p. 163.

- 26Guillermo de Osma, Fortuny, proust y los Ballets Rusos (Barcelona: Elba, 2010), pp. 47–48.

- 27Torres attended the production of Parade at the Liceu de Barcelona in 1917, and published an article defending it in November of that year. See Torres-García, “Un ballet rus de picasso: Parade,” La Revista (Barcelona) no. 53 (December 1, 1917):428.