Wartime espionage, and a search for “Latin Americanness” in artistic practices, was the dual mission that sent Lincoln Kirstein to Latin America in the 1940s. This essay charts these travels in relation to shifting currents in artistic languages and geopolitics—and their part in shaping MoMA’s early collection of art from Latin America.

This text is drawn from the catalogue for the exhibition Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern.

In the 1940s Lincoln Kirstein, through his affiliation with The Museum of Modern Art, became one of the most important authorities on Latin American art in the United States. Although he was associated with MoMA in the 1930s, it was not until anxieties about fascist incursion into the Americas escalated with the onset of World War II that Kirstein’s work for the Museum began to focus on Latin American art. He was directly involved in the institution’s first forays into the exhibition and collection of works from this region, and played a major role in shaping the Museum’s initial conception of art from Latin America as an aesthetic category in itself. In 1941 and 1942 Kirstein made two lengthy trips to South America, taking extensive notes on works, artists, and collections, and he published essays and articles about his observations upon his return; his research ultimately resulted in the exhibition The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art in 1943. He also drafted a detailed three-year plan for the establishment of a Department of Latin American Art at MoMA. Although it was never realized, Kirstein outlined the steps, resources, and standards such a department would require.1“Preliminary Plan for the Formation of a Department of Latin American Art in the Museum of Modern Art.” Lincoln Kirstein Correspondence and Miscellany, folder 7-H, in The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York (hereafter cited as “MoMA Archives”).

Yet because of the Museum’s shifts in focus after the war, Kirstein’s contributions to the field of Latin American art history have, until now, been largely overlooked. While multiple factors shaped his collecting decisions—including personal preferences and cultural diplomacy—essentially Kirstein sought art that could be identified as “Latin American” through its expression of local character and traditions.

Nelson A. Rockefeller—an avid collector of modern art and an influential businessman who had lucrative investments in Latin America—resigned as president of MoMA’s Board of Directors in 1940 to become the Coordinator of Commercial and Cultural Relations for Latin America at the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) in Washington, D.C.2Through the 1940s Rockefeller was deeply involved in Latin American affairs. In addition to his post as Coordinator of the Office of Inter-American Affairs (1940–44), between 1940 and 1953 he held numerous administrative and directorial positions related to the region. He also had a special interest in collecting Latin American art. See Eva Cockcroft, “The United States and Socially Concerned Latin American Art: 1920–1970,” in The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970, (New York: Bronx Museum of the Arts/Abrams, 1989), pp. 184–221. Established in 1938 by the U.S. State Department, the Cultural Relations division encouraged business investments in Latin America in part by promoting cultural interchange, which included sponsoring art exhibitions. By 1941 there were coordination committees in most Latin American republics whose goal was to block Axis influence in the Western Hemisphere by exerting control over media and cultural production.3See Gisela Cramer, “The Office of Inter-American Affairs and the Latin American Mass Media, 1940–1946,” Research Reports from the Rockefeller Archive Center (Fall/Winter 2001): 15. This paragraph is adapted from a passage in Michele Greet, Beyond National Identity: Pictorial Indigenism as a Modernist Strategy in Andean Art, 1920–1960 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), pp. 165–66. The Museum of Modern Art was an important partner in this process, organizing nineteen exhibitions of contemporary painting from the United States, which the OIAA circulated throughout Latin America.

In 1941 Rockefeller, in his new role as Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, awarded a federal contract to Kirstein to organize the American Ballet Caravan’s six-month tour of South America.4See Olga U. Herrera, American Intervention and Modern Art in South America (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017), p. 172. For an in-depth discussion of Kirstein’s collecting practice in relation to cultural policy and national defense, see Herrera’s chapter “The Art of Defense/The Defense of Art: Lincoln Kirstein and the Modern Art Acquisition Trip to South America, 1942,” pp. 168–206. She cites the “General Report to the Coordinator of Commercial and Cultural Relations between the American Republics,” NAR Personal Papers, RG 4, Series III4L, box 101, folder 966, Rockefeller Archive Center (hereafter “RAC”). Memo, Margaret Goodrich to Mrs. Brennan, May 3, 1950, NAR Personal Papers, RG4, Projects, Kirstein, Lincoln 1932–1966, box 100, folder 965, RAC. This appointment also allowed Kirstein to make connections with numerous visual artists, recording his observations in letters to MoMA’s director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr.5See Lincoln Kirstein, letter to Alfred H. Barr, July 20 (no year listed, presumably 1941). Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Papers (hereafter “AHB”) I.A.102, MoMA Archives. Because of the experience and contacts Kirstein had gained during his first venture, Rockefeller turned to him again in 1942 when seeking an envoy to South America for the OIAA. In the same year, Rockefeller made a significant monetary donation to the Museum, establishing what became known as the Inter-American Fund, to initiate planned collecting of Latin American art, with the stipulation that funds be spent on “works of interest or quality.”6Alfred H. Barr, Jr., draft of foreword to The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943). AHB I.A.106, MoMA Archives, p. 3. See also Cockcroft, “The United States and Socially Concerned Latin American Art.” Partly as a cover for the trip’s political purposes, Kirstein was engaged to undertake a collecting mission for the Museum and, upon his return, received a memo from Stephen C. Clark (a member of MoMA’s acquisitions committee) naming Kirstein “Consultant on Latin-American Art” to The Museum of Modern Art.7Stephen C. Clark, memo to Lincoln Kirstein, October 26, 1942, Kirstein, I.A., MoMA Archives. The position was a title only, and was uncompensated. In the summer of 1942 Barr traveled to Mexico and Cuba, while Kirstein returned to South America (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Uruguay) to make purchases for the collection using resources from the Inter-American Fund.8Barr was not an official envoy of the OIAA, but rather conceived of his participation as “a voluntary contribution made to the defense effort over and above the Museum’s normal activity.” Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Report of the Director: What Good Is Art in a Time of War? What Good Are Art Museums?,” in The Year’s Work, MoMA annual report (July 1, 1940–June 30, 1941), p. 6. Quoted in Herrera, American Intervention and Modern Art in South America, p. 170.

Kirstein’s trip thus had a dual purpose. Outwardly, it was staged as a voyage to assess the state of contemporary art in Latin American cities, to purchase works for the Museum, and to establish contacts for future cultural exchange. Covertly, Kirstein would gather information on the degree to which Axis agents had penetrated Brazil, Argentina, and Chile, and would report to the OIAA on the effectiveness of the U.S. diplomatic corps in managing these advances.9A letter from Nelson Rockefeller to General Hershey notes that Kirstein “has been selected by this Office [OIAA] to make a trip of a confidential nature to certain sections of Central and South America.” Nelson A. Rockefeller, letter to General Hershey, III4L, box 101, folder 966, RAC. I am grateful to Olga Herrera for retrieving this document. For more on Kirstein’s work for the OIAA, see Herrera, American Intervention and Modern Art in South America, p. 170. Because the trip was organized in part as a front for wartime espionage, Kirstein’s purchases have often been dismissed as unduly driven by expediency. Although a number of his acquisitions were out of keeping with what would prove to be the dominant trends in modernism, he obtained many important works in a range of styles, by artists both established and unknown, and his vision helped form the basis of MoMA’s subsequent engagements with Latin American art.10Kirstein also helped several young artists whom he met during his travels to organize exhibitions in New York, such as Luis Herrera Guevara and Demetrio Urruchúa, who exhibited at the Durlacher Brothers gallery in 1943. Note from Kirk Askew, December 9, 1942. Kirstein 7-A, MoMA Archives.

Kirstein’s tastes at the time of his trip tended toward modes of art making that were losing their cutting edge. In the 1930s, with the advent of the Great Depression, many artists in the Americas felt that the formalist experiments of the European avant-gardes were devoid of human sentiment and lacked social purpose. Social realism and indigenism—approaches that exposed harsh social realities and critiqued the exploitation of the working class and native peoples—therefore emerged as means to address problems specific to the Americas. With the onset of World War II, however, national governments began to co-opt images of Native Americans and “typical” nonpolitical American scenes in an effort to promote hemispheric solidarity and the broader agenda of “Pan-Americanism”—that is, the belief in shared cultural, economic, and historical bonds between North and South America. Paintings such as Cocoanut Palms (1939) by Jordão de Oliveira of Brazil and Zambiza Song (1938) by Atahualpa Villacrés of Ecuador served this purpose, for example, when they were featured at the Latin American Exhibition of Fine and Applied Art held in conjunction with the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Appropriated to these ends, such images were deprived of much of their ability to spark social reform.11To justify its actions, including economic and military intervention in the countries to its south, the U.S. aggressively promoted the concept of Pan-Americanism. See Greet, Beyond National Identity, 13.

While Pan-Americanism as a political and economic strategy had existed since the nineteenth century, it played a major role in foreign policy during World War II as a means to unite the American Republics against totalitarianism. Thus, the frequent association of artists who had worked in social realist modes in the 1930s with communism and socialism made their work a political liability during wartime. As a result, by 1939 artists began to turn away from both indigenism and social realism, and critics no longer viewed these as progressive artistic strategies, causing their impact as a form of social activism to wane. Artists who continued to paint national and regional subjects during the war years were therefore often criticized for catering to popular demand for the “typical” and the picturesque.

Writing in 1942, the year of Kirstein’s collecting trip, Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García, a key advocate for abstract modes of expression, asserted: “Falling into the archaeological; making South American pastiches. This should be avoided at all costs. And that is where all those who have wished to create autonomous art have fallen: Chileans, Mexicans, Peruvians, etc., without excluding personalities such as Diego Rivera. . . . Falling into the typical is another obstacle, no less dangerous.”12Joaquín Torres-García, “El nuevo arte de América” (1942), in Universalismo constructivo: Contribución a la unificación del arte y de la cultura de América (Buenos Aires: Poseidón, 1944); cited in Georges Roque, “Imágenes e indentidades: Europa y América,” Arte, historia e identidad en América (Mexico: UNAM, 1994), p. 1025. (Passage translated by the author.) Kirstein arrived in South America at a moment when the future direction of art was yet to be determined, and while the pendulum had not swung toward abstraction and more formalist explorations (as it would throughout the Americas by the 1950s), his predilection for the “typical” and the figurative aligned with exactly the sort of painting Torres-García disparaged. Kirstein tended to spurn abstract compositions and avoided politically volatile themes, instead selecting works that perpetuated a depoliticized, didactic version of indigenism, serving a Pan-Americanist agenda.

While Kirstein maintained specific criteria for the selection of the works he purchased for MoMA, following the Museum’s objectives, his own penchants, and inevitable diplomatic exigencies,13Prior to Kirstein’s collecting mission, MoMA had already received works by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros as gifts from trustees and donors. Gifts of work by Brazilian Candido Portinari in 1939 and donations of works by Bolivian and Cuban artists followed. By 1941 MoMA had 110 works by Latin American artists—but representing only eleven artists from four countries. Although the Mexican collection was strong, there were major gaps in the Museum’s holdings from Latin America overall. Kirstein’s collecting mission was meant to address this disparity. Barr, draft of foreword to The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. he was constrained by the brevity of his stay, the availability of procurable works, and budgetary concerns. As Barr himself would observe of MoMA’s Latin American collection in 1943: “The fact that some artists are represented with minor works is due partly to the lack of funds and partly because in some cases better pictures were not available.”14Alfred H. Barr, Jr., letter to Emilio Pettoruti (cc. Grace McCann Morley), October 13, 1943. AHB I.A.104, MoMA Archives. Kirstein’s guides from country to country also influenced his acquisitions, sometimes leading to omissions or excessive focus on figures of national renown. The contrast was particularly acute between Kirstein’s experiences in Brazil and Argentina (where independent agents accompanied him to artists’ studios) and in Peru (where his guide was a public-relations specialist who steered him to the studios of officially sanctioned artists teaching at the national art school).15See Da Veija [sic] Guignard notes; Urteaga, Mario notes; Berni, Antonio notes; and Sabogal, José notes. All Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives. These circumstances surely had an effect on his purchases.

Kirstein’s acquisitions, when assessed together, reveal much about his personal preferences and collecting philosophy. He had a fondness for intricate detail and craftsmanship and tended to focus on figurative works that demonstrate a connection to classicism (as seen in selections such as Antonio Berni’s New Chicago Athletic Club [Club atlético Nueva Chicago, 1937, discussed below). Despite his tendency to avoid abstraction and avant-garde experimentation, his choices reflect a decidedly modernist sensibility, albeit one aligned with social and magic realism in the United States. According to Kirstein, he selected works by artists who “have tried to assert their feeling for their time and place; artists who in fact attempted to declare independence from traditional European expression—or who . . . express what they have known best by virtue of their birth or bringing-up.”16Lincoln Kirstein, “Latin-American Painting: A Comparative Sketch,” 1943, p. 3. “Latin American Art Notes,” Kirstein, II.1, MoMA Archives. In other words, he sought art that evidenced local character and downplayed European influence.17Kirstein describes Latin America’s “semi-colonial” status and its need to be “weaned away from European sources” to assert a “national consciousness.” Lincoln Kirstein, “South American Painting,” Studio 128, no. 619 (October 1944): 106.

By the early 1940s, in cultural circles in Europe and the Americas, “Latin American art” was an established (and already contested) aesthetic category that had emerged outside Latin America, and was often defined according to the desires, tastes, and agendas of critics in Europe or the United States.18In 1924 the first survey exhibition of Latin American art was held at the Musée Galliéra in Paris. After that presentation, the survey show became an accepted format for the display of Latin American art on the world stage—although almost never in Latin American cities. Kirstein’s emphasis on local character led him to look beyond the artistic establishment for works by self-taught, popular, or what today might be deemed “outsider” artists. Indeed, a great many of his acquisitions were by artists who did not participate in “official” artistic circuits and whose reputations had not reached beyond regional spheres. The juxtaposition of modern and popular and/or ancient art in exhibitions and publications—as seen in the Mexican journal Forma or in Surrealist exhibitions in Paris—had long served the modernist objective of challenging traditional aesthetic hierarchies and associations.19On Forma, see Harper Montgomery, “Revolutionary Modernism: A ‘Museo de Arte Moderno’ Rehearsed in Print in Mexico City, 1926–1928,” in Michele Greet and Gina McDaniel Tarver, eds., Art Museums of Latin America: Structuring Representation, Research in Art Museums and Exhibitions series (New York: Routledge, 2018), 221–35. On Surrealist exhibition practices, see Louise Tythacott, Surrealism and the Exotic (London: Routledge, 2003). For example, in 1927 an exhibition of paintings by Yves Tanguy included ancient objects from Peru, Mexico, Columbia, and the northwest coast of the United States. When implemented by a U.S. collector, however, this practice presented a false equivalency between the trained and the untrained in the eyes of uninitiated foreign viewers, and tended to efface distinctions between deliberately naïve appropriations and actual popular traditions, and to foreground spontaneous expression as a marker of Latin American artistic identity. Moreover, Kirstein’s quest to unearth raw or “authentic” local talent echoed colonial voyages of discovery in centuries past. Indeed, Kirstein himself commented in a letter to Barr on the “intellectual imperialism” of visiting Northerners.20Kirstein, letter to Barr, June 19, 1942. AHB, I.A.51, MoMA Archives. While his approach led to some very interesting acquisitions, it also revealed ingrained prejudices and primitivist expectations in the United States and Europe.

Kirstein’s first stop, in May 1942, was Brazil (Rio de Janeiro and then São Paulo), where he acquired works by thirteen artists. Here he focused on collecting work by figures who were currently active in the country’s art scene, which led to the omission of pieces by some of the most important artists associated with the avant-gardes of the 1920s and 1930s. Conspicuously absent from his purchases were works by Tarsila do Amaral, Anita Malfatti, Vicente do Rego Monteiro, Emilio di Cavalcanti, and Ismael Nery. Some of these artists were no longer participating in Brazil’s artistic milieu, and it is possible that their work may not have been readily obtainable—still, their absence from his collecting purview indicates Kirstein’s prioritizing of emerging or underrecognized talent, and perhaps a desire to position himself as a pioneer of sorts. He refused to visit Maria Martins’s studio because critics had communicated to him that her work was seen as a “colossal joke” in Rio,21Ibid. and he angered the prominent artist Candido Portinari when he acquired works by (in Kirstein’s words) “a gang who had never even been his one-time pupils.”22Ibid. Since MoMA had recently held the exhibition Portinari of Brazil (October 9–November 17, 1940), from which they had acquired works by the artist, Kirstein did not pursue additional purchases. His experience in Brazil was tainted by the oppressive atmosphere of the increasingly authoritarian regime of dictator Getúlio Vargas. As Kirstein wrote to Barr: “The intellectual and creative life of Brazil is suffocated under the Benevolent Despotism of Vargas—a more crippling one than Hitler’s since its enervating bribery arouses no protest but only the slow extinction of talent by the systematic sapping of morale.”23Kirstein, letter to Barr, June 19, 1942. AHB, I.A.51, MoMA Archives. The challenging cultural climate during his visit significantly shaped Kirstein’s selections.

The key Brazilian modernist whose works Kirstein purchased was Alberto da Veiga Guignard. Like many of the artists mentioned above, Guignard had spent considerable time in Europe, but in his notes Kirstein portrays him as a decidedly provincial figure, remarking on the fact that Guignard taught children at a local school and gave most of his paintings away to friends.24Da Veija [sic] Guignard notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives. Kirstein makes no mention of his European training nor of his connections to important modernists such Anita Malfatti and Emilio Pettoruti, of whom Guignard painted striking portraits.25Kirstein did later mention Guignard’s European training in his 1944 article “South American Painting,” p. 110.

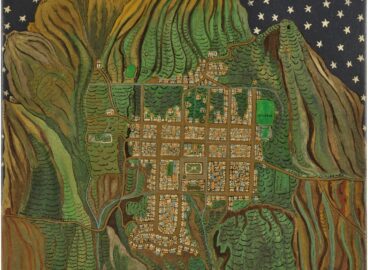

The painting by Guignard that Kirstein acquired for MoMA was created after a preliminary drawing had been submitted to Kirstein for approval. It depicts the town of Ouro Preto during a Saint John’s Eve celebration—an occasion also featured in two other Kirstein purchases: a painting by Heitor dos Prazeres and a tile work by Paulo Rossi Osir.26Da Veija [sic] Guignard notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives. Saint John’s Day is one of Brazil’s most important festivals; it takes place every June 24 to mark the winter solstice and the end of the rainy season. Guignard rendered the picturesque central plaza of Ouro Preto from above, as if seen from the perspective of one of the colored lanterns floating in the night sky. The church of Saint Francis of Assisi is clearly recognizable on the main plaza, but Guignard has compressed and embellished the town’s colonial architecture with additional churches and ornate details. For Kirstein, this type of painting provided a glimpse into an unknown world and captured the defining elements of the nation.

One of the most striking acquisitions from Kirstein’s Brazil trip—for which he paid only thirty dollars—was Still Life with View of the Bay of Guanabara (1937), by the eighty-two-year-old retired schoolteacher José Bernardo Cardoso, Jr. The painting shows a meticulously drawn, symmetrically arranged bouquet in the center of a table; next to it is a Tetrio Sphinx caterpillar, a species native to Brazil. On each corner of the table are different types of moths, rendered with such scientific precision as to suggest the artist was working from Lepidoptera specimens. This emphasis on taxonomic accuracy hearkens back to nineteenth-century scientific illustrations, but the shifting perspective flattens the image with modernist perspectival disruptions. Throughout the composition there is an emphasis on pattern and geometry—the checkered tabletop, the grid pattern on the floor, the mosaic tiles—and each hue is circumscribed within a corresponding shape. The fastidious accuracy of the specimens and the flat decorative space they occupy bring together artistic license and scientific precision.

Kirstein’s purchases of works by Guignard and Cardoso reveal his taste for compositions rendered in painstakingly minute detail, a predilection expressed in the text he wrote for MoMA’s Americans 1943: Realists and Magic Realistscatalogue.27Dorothy C. Miller and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., eds., American Realists and Magic Realists (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943). Describing the works in that exhibition, Kirstein praised the “crisp hard edges, tightly indicated forms,” and the way the artists “completely achieved visual fact.”28Lincoln Kirstein, introduction to American Realists and Magic Realists, ed. Dorothy C. Miller and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943), p. 7. Both the Guignard and the Cardoso offer creative reimaginings of identifiable places, portrayed from their unique points of view—adding and rearranging elements and manipulating scale and perspective. For Kirstein, these images offered the perfect combination of “local character” and invention. Such visual affinities thread through the works that he promoted across the Americas. Whether consciously or not, by highlighting aesthetic similarities rather than differences, Kirstein’s selections emphasize cultural bonds and Pan-American unity at a moment when the rhetoric of Pan-Americanism dominated U.S. cultural policy.

By the time Kirstein arrived in Argentina, where he spent six weeks in the summer of 1942, he had hit his stride. In Buenos Aires, he visited at least thirty artists’ studios and saw the work of more than a hundred artists, spending far more money than he had in any other country and acquiring his most expensive pictures there.29Kirstein, 11.2 travel notebook, pp. 27–29, MoMA Archives. His notes on this visit indicate a strong affinity for Argentine art and his pleasure at finding a well-developed art scene, which he saw as comparable to that in the United States.

One artist who was notably absent from his purchases in Argentina was the pioneering modernist Emilio Pettoruti. Kirstein’s reasons for rejecting Pettoruti were ostensibly political; in a letter to Barr, he wrote that the Argentine artist was an “avant-fascist” and that purchasing his paintings would be a “slap in the face to decent artists here.”30See Gustavo Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido: Avatares del Club Atlético Nueva Chicago,” in Berni y sus contemporáneos (Buenos Aires: MALBA—Colección Costantini, 2005), p. 66. Buntinx cites Kirstein, letter to Barr, July 8, 1942, Kirstein, I.A., MoMA Archives. Pettoruti adamantly denied these accusations, and wrote to Barr saying he believed that his competitors had passed this misinformation to Kirstein.31Pettoruti, letter to Barr, September 3, 1943. AHB I.A.104, MoMA Archives. The rumor may have provided Kirstein a convenient excuse not to acquire work that did not especially appeal to him.

Kirstein identified two camps in Argentine art in the early 1940s: Pettoruti’s hard-edge post-Cubism and Antonio Berni’s Nuevo Realismo (or New Realism, an approach akin to social realism in the United States), pitting the two sides against each other.32See Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 72. See also Pettoruti, letter to Barr, September 3, 1943. AHB, I.A.104, MoMA Archives. See also Miriam Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting and Exhibiting Work by Artists from Latin America,” in Latin American and Caribbean Art: MoMA at El Museo, El Museo del Barrio and The Museum of Modern Art (Madrid: Turner, 2004), pp. 98–100. Because of his preference for figurative modes, Kirstein sided with Berni.33Later, MoMA did acquire a small Pettoruti. See Barr, letter to Pettoruti, February 23, 1943. AHB I.A.104, MoMA Archives. His acquisition of Berni’s New Chicago Athletic Club was something of a coup. The piece, for which Kirstein paid one thousand dollars—half the artist’s asking price—was, at nearly six by ten feet, by far the largest painting he acquired during his travels, as well as the most expensive. In the manner of Gustave Courbet’s Burial at Ornans (1849–50), Berni clearly meant to challenge the conventions of academic history painting in rendering this ragtag soccer team from the outskirts of Buenos Aires at such a grand scale and in such acute detail. The image recalls the artist’s brief Surrealist interlude in the early 1930s: the deteriorating arcade of the Mercado de Hacienda de Mataderos (an important neighborhood landmark that had closed in 1931),34Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 69. the oddly tilting space, extreme perspective and contrast, and low clouds all bring to mind works by Giorgio de Chirico. Posed in this incongruous setting are sixteen boys of various racial mixes. Argentine art historian Gustavo Buntinx, who has written extensively about this painting, points out that the image corresponds to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” rhetoric, positioning Pan-American unity against totalitarianism: Berni’s mestizos—figures of mixed racial heritage—offer a clear challenge to the Nazis’ promotion of racial purity.35In an attempt to improve relations with Latin America, Franklin D. Roosevelt established the “Good Neighbor” policy in 1933, which affirmed that no nation could interfere in the affairs of another nation. Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 67. Buntinx has identified the precise history of this soccer team, even noting that they had qualified for a championship match in 1936 in a victory against another local athletic club, with a score of 5 to 0.36Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 69. Berni’s subjects were real contemporary urban youths, a sector of society overlooked by both politicians and contemporary artists.37Ibid., p. 67.

Berni hoped MoMA’s acquisition of his painting would foreground the connection between his work and that of the U.S. social realists, writing in a letter to Kirstein: “It gives me great satisfaction that one of my paintings figures in a U.S. museum. I hope that this first contact with the American public—contact that you have facilitated—is a truly spiritual communication, affirmation of a New Realism, that is the focus of so many American artists and the path towards a continental artistic unity”.38Antonio Berni, letter to Kirstein, August 13, 1942. The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 224.3, MoMA Archives. Interestingly, Berni, too, adopted the language of Pan-Americanism, stressing hemispheric rather than transatlantic links between artists, perhaps as a tactic to ingratiate himself with his North American patron. The painting’s large size, technique, and groundbreaking content make it one of Kirstein’s most important acquisitions and an archetypal example of the kind of work he felt should represent MoMA’s Latin American collection. Unfortunately, MoMA exhibited the painting only three times, all in 1943, limiting opportunities to develop a cross-cultural understanding of the work.39Berni’s painting was included in MoMA’s 1943 exhibition of Latin American Art, and was displayed again in galleries twice later that year. Until now, the painting had not been shown again at The Museum of Modern Art, although it was included in the exhibition of MoMA’s collection at El Museo del Barrio in 2004. It was, however, borrowed by the Bronx Museum of the Arts in 1988–89 for inclusion in the traveling exhibition The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970 and was loaned to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, in 2012. See Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting,” p. 100.

While in Argentina, Kirstein also purchased works by several eminent women artists, including Raquel Forner, whom he praised as “one of the most important contemporary Argentine painters.”40Forner, Raquel notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives. In his notes on Forner’s Desolation (Desolación, 1942), Kirstein describes the subject as “root forms and twisted tree trunks from the natural elements of the country of Nahuel Huapi around the lake country of Argentina.”41Ibid. While this sort of tree formation is typical of that region, Kirstein’s desire to connect the image to an indigenous Argentine environment points again to his tendency to highlight local rather than European sources, emphasizing the “Latin Americanness” of his purchases. Interestingly, he makes no mention of the bombed planes and four tiny white parachutes in the ominous sky—clear references to the horrors of war—rather, he envisions the scene as a “characteristic” landscape. Like many Argentine artists, Forner spent time in Paris (1929–31), where she became acquainted with Surrealism and incorporated some of the movement’s nightmarish interpretation of the natural world into her work as a form of political commentary. Kirstein declined to acknowledge this European-inflected aspect of Forner’s work.

From Argentina, Kirstein took a ferry to Uruguay. In Montevideo he acquired a painting by the most important Latin American avant-garde artist of the time, Joaquín Torres-García, as well as two works by his sons, Augusto and Horacio.42Kirstein also attempted to procure a painting by another key modernist, Pedro Figari, but was unable to do so because the estate was in dispute after the artist’s death in 1938. MoMA acquired a Figari in 1943 as a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Robert Wood Bliss. The painting Kirstein selected by Torres-García, The Port (1942), says a great deal about the collector’s aesthetic preferences and distaste for abstraction. Torres-García had made a name for himself as a progressive artist in Europe and the Americas with his development of “constructive universalism”—a method of structuring his compositions based on an asymmetrical grid interspersed with graphic symbols. He developed this signature style while living in Paris in 1930 and continued employing it after he returned to Uruguay in 1934. By the time of Kirstein’s visit in 1942, Torres-García was working in several styles at once: he was still producing grid paintings, but also more naturalistic compositions, including images of cities and ports in a style he had honed in Paris around 1928.43See online catalogue raisonné for works Torres-García painted in 1942: http://torresgarcia.com/catalogue/index.php. The Port,while composed of flat geometric structures, hearkens back to this earlier era in his career: it is eminently legible, with recognizable buildings, restaurants, a train, a horse-drawn cart, large and small ships in the harbor, and figures going about their daily routines; hovering in the sky is a large fish—a symbol Torres-García frequently incorporated in his grid paintings. Kirstein selected this relatively figurative work over one of the artist’s more abstract grid paintings, calling the forms “more recognizable than the purely decorative or abstracter epochs.”44Torres-García, Joaquín notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives. Kirstein articulated his distaste for abstraction and paintings that are not “fully realized” in “The State of Modern Painting,” Harper’s Magazine 197, no. 1181 (October 1948): 47–53.

After Uruguay, Kirstein traveled to Chile, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, where he selected works that depicted local indigenous subjects, while avoiding politically charged imagery. MoMA had recently acquired a number of Chilean works: a drawing and an oil painting, Listen to Living (Escuchar vivir, 1941), by Roberto Matta, as well as several works featured in the Toledo Museum of Art’s 1941 Chilean Contemporary Art Exhibition. Kirstein purposefully chose not to purchase works by any of the artists that had been part of that wave, focusing on lesser-known figures in Chile.45See Herrera, American Intervention, p. 185. She cites Kirstein, letter to William L. Clark, March 26, 1942, NAR Personal Papers, RG 4, Series III4L, folder 966, box 101, RAC. It would seem that his goal in building MoMA’s Latin American holdings was to represent a wide selection of practitioners, rather than to intensify the focus on artists already in the Museum’s collection. His acquisition process was more about breadth than depth.

In Peru, Kirstein encountered a sharply divided artistic environment, leading him to make several purchases out of apparent diplomatic obligation. The artist José Sabogal was the director of the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Lima—a powerful position indeed. Sabogal hired his loyal followers to teach at the school and discouraged deviations from his aesthetic program, ensuring that his version of indigenism became a kind of national institution. By 1937 exasperated artists and critics in Peru were calling for reforms to the school’s curriculum.46“Debe ser suprimida o reformada la Escuela nacional de Bellas Artes,” La prensa (February 1937); cited in Luís Fernández Prada, La pintura en el Perú (5 años de ambiente artístico) (Lima: Sociedad de Bellas Artes del Perú and Imp. gráfica Stylo., 1942), p. 6. In the year of Kirstein’s visit, animosity toward Sabogal and his paintings had intensified, resulting in a scathing critique in the Peruvian press.47Prada, La pintura en el Perú. Kirstein admitted to abhorring the work of Sabogal and his followers, and to making a number of purchases only out of obligation. “The dealings with Sabogal,” he wrote, “must be written off at least three-quarters to good will . . . and good neighbor policy in general.”48Kirstein’s notes on purchases for the Inter-American Fund. Early Museum History II.15.a, MoMA Archives. Kirstein did, however, also obtain Mario Urteaga’s Burial of an Illustrious Man (Entierro del patriota, 1936). Urteaga was a self-trained artist, unaffiliated with Sabogal, whom Kirstein described in his notes as the “finest painter in Peru.”49Urteaga, Mario notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives.

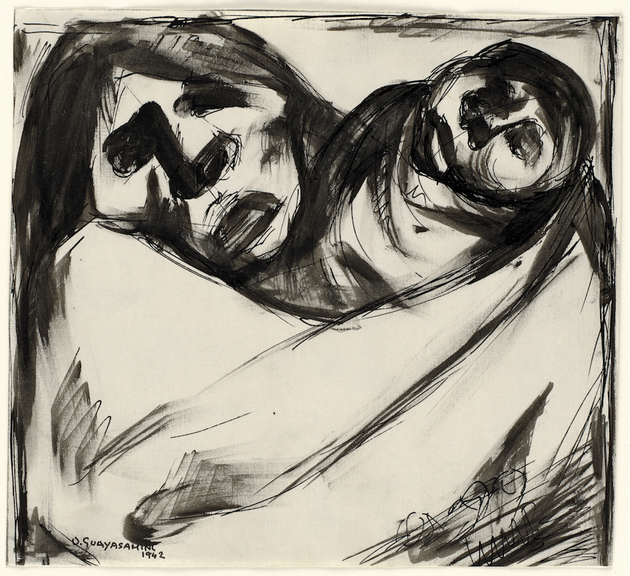

Finally, in Ecuador and Colombia, Kirstein maintained his focus on emerging talent, purchasing works by Gonzalo Ariza, Oswaldo Guayasamín, and Diógenes Paredes—all featuring local scenes without explicit social or political commentary50See Greet, Beyond National Identity, pp. 162–84.—always managing to provide the Museum with examples of local trends.

Kirstein’s 1942 trip resulted in the acquisition of 141 works altogether, making up a substantial portion of MoMA’s Latin American holdings for years to come.51This number reflects works that actually arrived in New York, but not necessarily every intended acquisition. His purchases, with the addition of the pieces Barr acquired in Mexico and Cuba and twenty-nine donated works, formed the basis of MoMA’s first survey exhibition of Latin American art in 1943.52The stimulating effect of the Inter-American fund prompted other gifts, including works by Uruguayan, Cuban, and Mexican artists. Barr noted, however, that the collection was still incomplete in 1943 because it represented only ten of the twenty-one American republics and included very few sculptures and photographs. Barr, draft of foreword to The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. See also Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting,” p. 54; and Cathleen M. Paquette, “Public Duties, Private Interests: Mexican Art at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, 1929–1954” (Ph.D diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2002), pp. 216–18. Kirstein wrote the essay for the catalogue, which, along with his 1944 article in the Studio, was among the first in the United States to bring a rigorous critical sensibility to the field of contemporary Latin American art. Unfortunately, Kirstein was not able to determine the final shape of the exhibition: he was drafted into the army three weeks prior to its installation (Dorothy C. Miller, MoMA’s Associate Curator of Painting, took over the project). While Kirstein’s catalogue essay was organized by country, the exhibition did not follow this configuration; instead, it opened with work by the “modern primitives”—described by Barr as “artists of the people, unsophisticated and without academic training”—in the first gallery, and saved the work of those with European connections or who had attended art school for the later galleries.53“Latin American Art in the Museum’s Collection,” AHB, I.A.106, MoMA Archives. Barr would also employ this organizational strategy for MoMA’s 1954–55 XXVth Anniversary Exhibition: Paintings from the Museum Collection, which included a section featuring the “Modern Primitives.” https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2800. This foregrounding of untrained artists shed light on Kirstein’s collecting preferences and introduced some extremely innovative work to U.S. audiences—but also served to reinforce the notion that art from south of the border was naïve and disconnected from North American and European modernist networks. Nonetheless, this exhibition, while biased in some of its assumptions, set an important precedent for the display and assessment of Latin American art in the United States.

Upon his return to New York in 1942, Kirstein wrote a draft proposal for a Department of Latin American Art at MoMA. In correspondence with René d’Harnoncourt, a highly accomplished expert in Mexican art and guest curator at MoMA in 1940–41 (who would become MoMA’s director in 1949), Kirstein hashed out an ambitious plan that would establish, through cultural exchanges, collection building, and exhibitions, “better mutual understanding of contemporary trends and achievements in painting, sculpture, architecture, and the urban industrial arts of the Hemisphere.”54René d’Harnoncourt’s comments, dated October 17, 1942, on “Kirstein’s Preliminary Plan for the Formation of a Department of Latin American Art in the Museum of Modern Art.” Lincoln Kirstein Correspondence and Miscellany, folder 7-H, MoMA Archives. On d’Harnoncourt as curator of Mexican Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1930–31, see Anna Indych-López, Muralism without Walls: Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros in the United States, 1927–1940 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009), pp. 116–28. In November 1942, John E. Abbott, Executive Vice-President of MoMA, wrote to Rockefeller: “We are going ahead with the organization of a skeleton South American department through which we hope to keep alive the various contacts which have been made during the past two years through correspondence, the sending of catalogues and books, and the like.”55John E. Abbott, letter to Nelson Rockefeller, November 24, 1942. Kirstein, I.D., MoMA Archives. Kirstein laid out a detailed plan for the department over the course of 1943 and 1944, but his deployment curtailed its implementation, and MoMA’s department of Latin American art was never realized as such.

With the end of World War II, the U.S. government dismantled the OIAA Art Section and discontinued its cultural projects in Latin America. MoMA, too, turned its attentions away from art of this region, rarely displaying any of the works Kirstein had acquired.56See Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 74. When Kirstein returned from the war, he became deeply engaged in a new project that shifted his focus away from Latin American art: building what would become the New York City Ballet. His distance from MoMA in the years following his trip drew energy away from his vision for the Museum’s collection of Latin American art. Moreover, with Kirstein’s preference for figuration and “typical” scenes, the works he collected in 1942 often did not concur with Barr’s more formalist perspective, which took clear precedence after the war. MoMA’s increased focus on Latin American art in recent years, however, has led to an important re-examination of Kirstein as a pioneering voice in shaping ideas about Latin American art in the United States.

- 1“Preliminary Plan for the Formation of a Department of Latin American Art in the Museum of Modern Art.” Lincoln Kirstein Correspondence and Miscellany, folder 7-H, in The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York (hereafter cited as “MoMA Archives”).

- 2Through the 1940s Rockefeller was deeply involved in Latin American affairs. In addition to his post as Coordinator of the Office of Inter-American Affairs (1940–44), between 1940 and 1953 he held numerous administrative and directorial positions related to the region. He also had a special interest in collecting Latin American art. See Eva Cockcroft, “The United States and Socially Concerned Latin American Art: 1920–1970,” in The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970, (New York: Bronx Museum of the Arts/Abrams, 1989), pp. 184–221.

- 3See Gisela Cramer, “The Office of Inter-American Affairs and the Latin American Mass Media, 1940–1946,” Research Reports from the Rockefeller Archive Center (Fall/Winter 2001): 15. This paragraph is adapted from a passage in Michele Greet, Beyond National Identity: Pictorial Indigenism as a Modernist Strategy in Andean Art, 1920–1960 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), pp. 165–66.

- 4See Olga U. Herrera, American Intervention and Modern Art in South America (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2017), p. 172. For an in-depth discussion of Kirstein’s collecting practice in relation to cultural policy and national defense, see Herrera’s chapter “The Art of Defense/The Defense of Art: Lincoln Kirstein and the Modern Art Acquisition Trip to South America, 1942,” pp. 168–206. She cites the “General Report to the Coordinator of Commercial and Cultural Relations between the American Republics,” NAR Personal Papers, RG 4, Series III4L, box 101, folder 966, Rockefeller Archive Center (hereafter “RAC”). Memo, Margaret Goodrich to Mrs. Brennan, May 3, 1950, NAR Personal Papers, RG4, Projects, Kirstein, Lincoln 1932–1966, box 100, folder 965, RAC.

- 5See Lincoln Kirstein, letter to Alfred H. Barr, July 20 (no year listed, presumably 1941). Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Papers (hereafter “AHB”) I.A.102, MoMA Archives.

- 6Alfred H. Barr, Jr., draft of foreword to The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943). AHB I.A.106, MoMA Archives, p. 3. See also Cockcroft, “The United States and Socially Concerned Latin American Art.”

- 7Stephen C. Clark, memo to Lincoln Kirstein, October 26, 1942, Kirstein, I.A., MoMA Archives. The position was a title only, and was uncompensated.

- 8Barr was not an official envoy of the OIAA, but rather conceived of his participation as “a voluntary contribution made to the defense effort over and above the Museum’s normal activity.” Alfred H. Barr, Jr., “Report of the Director: What Good Is Art in a Time of War? What Good Are Art Museums?,” in The Year’s Work, MoMA annual report (July 1, 1940–June 30, 1941), p. 6. Quoted in Herrera, American Intervention and Modern Art in South America, p. 170.

- 9A letter from Nelson Rockefeller to General Hershey notes that Kirstein “has been selected by this Office [OIAA] to make a trip of a confidential nature to certain sections of Central and South America.” Nelson A. Rockefeller, letter to General Hershey, III4L, box 101, folder 966, RAC. I am grateful to Olga Herrera for retrieving this document. For more on Kirstein’s work for the OIAA, see Herrera, American Intervention and Modern Art in South America, p. 170.

- 10Kirstein also helped several young artists whom he met during his travels to organize exhibitions in New York, such as Luis Herrera Guevara and Demetrio Urruchúa, who exhibited at the Durlacher Brothers gallery in 1943. Note from Kirk Askew, December 9, 1942. Kirstein 7-A, MoMA Archives.

- 11To justify its actions, including economic and military intervention in the countries to its south, the U.S. aggressively promoted the concept of Pan-Americanism. See Greet, Beyond National Identity, 13.

- 12Joaquín Torres-García, “El nuevo arte de América” (1942), in Universalismo constructivo: Contribución a la unificación del arte y de la cultura de América (Buenos Aires: Poseidón, 1944); cited in Georges Roque, “Imágenes e indentidades: Europa y América,” Arte, historia e identidad en América (Mexico: UNAM, 1994), p. 1025. (Passage translated by the author.)

- 13Prior to Kirstein’s collecting mission, MoMA had already received works by Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros as gifts from trustees and donors. Gifts of work by Brazilian Candido Portinari in 1939 and donations of works by Bolivian and Cuban artists followed. By 1941 MoMA had 110 works by Latin American artists—but representing only eleven artists from four countries. Although the Mexican collection was strong, there were major gaps in the Museum’s holdings from Latin America overall. Kirstein’s collecting mission was meant to address this disparity. Barr, draft of foreword to The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

- 14Alfred H. Barr, Jr., letter to Emilio Pettoruti (cc. Grace McCann Morley), October 13, 1943. AHB I.A.104, MoMA Archives.

- 15See Da Veija [sic] Guignard notes; Urteaga, Mario notes; Berni, Antonio notes; and Sabogal, José notes. All Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives.

- 16Lincoln Kirstein, “Latin-American Painting: A Comparative Sketch,” 1943, p. 3. “Latin American Art Notes,” Kirstein, II.1, MoMA Archives.

- 17Kirstein describes Latin America’s “semi-colonial” status and its need to be “weaned away from European sources” to assert a “national consciousness.” Lincoln Kirstein, “South American Painting,” Studio 128, no. 619 (October 1944): 106.

- 18In 1924 the first survey exhibition of Latin American art was held at the Musée Galliéra in Paris. After that presentation, the survey show became an accepted format for the display of Latin American art on the world stage—although almost never in Latin American cities.

- 19On Forma, see Harper Montgomery, “Revolutionary Modernism: A ‘Museo de Arte Moderno’ Rehearsed in Print in Mexico City, 1926–1928,” in Michele Greet and Gina McDaniel Tarver, eds., Art Museums of Latin America: Structuring Representation, Research in Art Museums and Exhibitions series (New York: Routledge, 2018), 221–35. On Surrealist exhibition practices, see Louise Tythacott, Surrealism and the Exotic (London: Routledge, 2003). For example, in 1927 an exhibition of paintings by Yves Tanguy included ancient objects from Peru, Mexico, Columbia, and the northwest coast of the United States.

- 20Kirstein, letter to Barr, June 19, 1942. AHB, I.A.51, MoMA Archives.

- 21Ibid.

- 22Ibid. Since MoMA had recently held the exhibition Portinari of Brazil (October 9–November 17, 1940), from which they had acquired works by the artist, Kirstein did not pursue additional purchases.

- 23Kirstein, letter to Barr, June 19, 1942. AHB, I.A.51, MoMA Archives.

- 24Da Veija [sic] Guignard notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives.

- 25Kirstein did later mention Guignard’s European training in his 1944 article “South American Painting,” p. 110.

- 26Da Veija [sic] Guignard notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives.

- 27Dorothy C. Miller and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., eds., American Realists and Magic Realists (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943).

- 28Lincoln Kirstein, introduction to American Realists and Magic Realists, ed. Dorothy C. Miller and Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1943), p. 7.

- 29Kirstein, 11.2 travel notebook, pp. 27–29, MoMA Archives.

- 30See Gustavo Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido: Avatares del Club Atlético Nueva Chicago,” in Berni y sus contemporáneos (Buenos Aires: MALBA—Colección Costantini, 2005), p. 66. Buntinx cites Kirstein, letter to Barr, July 8, 1942, Kirstein, I.A., MoMA Archives.

- 31Pettoruti, letter to Barr, September 3, 1943. AHB I.A.104, MoMA Archives.

- 32See Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 72. See also Pettoruti, letter to Barr, September 3, 1943. AHB, I.A.104, MoMA Archives. See also Miriam Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting and Exhibiting Work by Artists from Latin America,” in Latin American and Caribbean Art: MoMA at El Museo, El Museo del Barrio and The Museum of Modern Art (Madrid: Turner, 2004), pp. 98–100.

- 33Later, MoMA did acquire a small Pettoruti. See Barr, letter to Pettoruti, February 23, 1943. AHB I.A.104, MoMA Archives.

- 34Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 69.

- 35In an attempt to improve relations with Latin America, Franklin D. Roosevelt established the “Good Neighbor” policy in 1933, which affirmed that no nation could interfere in the affairs of another nation. Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 67.

- 36Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 69.

- 37Ibid., p. 67.

- 38Antonio Berni, letter to Kirstein, August 13, 1942. The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition Records, 224.3, MoMA Archives.

- 39Berni’s painting was included in MoMA’s 1943 exhibition of Latin American Art, and was displayed again in galleries twice later that year. Until now, the painting had not been shown again at The Museum of Modern Art, although it was included in the exhibition of MoMA’s collection at El Museo del Barrio in 2004. It was, however, borrowed by the Bronx Museum of the Arts in 1988–89 for inclusion in the traveling exhibition The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970 and was loaned to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, in 2012. See Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting,” p. 100.

- 40Forner, Raquel notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives.

- 41Ibid.

- 42Kirstein also attempted to procure a painting by another key modernist, Pedro Figari, but was unable to do so because the estate was in dispute after the artist’s death in 1938. MoMA acquired a Figari in 1943 as a gift from Mr. and Mrs. Robert Wood Bliss.

- 43See online catalogue raisonné for works Torres-García painted in 1942: http://torresgarcia.com/catalogue/index.php.

- 44Torres-García, Joaquín notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives. Kirstein articulated his distaste for abstraction and paintings that are not “fully realized” in “The State of Modern Painting,” Harper’s Magazine 197, no. 1181 (October 1948): 47–53.

- 45See Herrera, American Intervention, p. 185. She cites Kirstein, letter to William L. Clark, March 26, 1942, NAR Personal Papers, RG 4, Series III4L, folder 966, box 101, RAC.

- 46“Debe ser suprimida o reformada la Escuela nacional de Bellas Artes,” La prensa (February 1937); cited in Luís Fernández Prada, La pintura en el Perú (5 años de ambiente artístico) (Lima: Sociedad de Bellas Artes del Perú and Imp. gráfica Stylo., 1942), p. 6.

- 47Prada, La pintura en el Perú.

- 48Kirstein’s notes on purchases for the Inter-American Fund. Early Museum History II.15.a, MoMA Archives.

- 49Urteaga, Mario notes. Kirstein, I.G., MoMA Archives.

- 50See Greet, Beyond National Identity, pp. 162–84.

- 51This number reflects works that actually arrived in New York, but not necessarily every intended acquisition.

- 52The stimulating effect of the Inter-American fund prompted other gifts, including works by Uruguayan, Cuban, and Mexican artists. Barr noted, however, that the collection was still incomplete in 1943 because it represented only ten of the twenty-one American republics and included very few sculptures and photographs. Barr, draft of foreword to The Latin-American Collection of the Museum of Modern Art. See also Basilio, “Reflecting on a History of Collecting,” p. 54; and Cathleen M. Paquette, “Public Duties, Private Interests: Mexican Art at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, 1929–1954” (Ph.D diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2002), pp. 216–18.

- 53“Latin American Art in the Museum’s Collection,” AHB, I.A.106, MoMA Archives. Barr would also employ this organizational strategy for MoMA’s 1954–55 XXVth Anniversary Exhibition: Paintings from the Museum Collection, which included a section featuring the “Modern Primitives.” https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2800.

- 54René d’Harnoncourt’s comments, dated October 17, 1942, on “Kirstein’s Preliminary Plan for the Formation of a Department of Latin American Art in the Museum of Modern Art.” Lincoln Kirstein Correspondence and Miscellany, folder 7-H, MoMA Archives. On d’Harnoncourt as curator of Mexican Arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1930–31, see Anna Indych-López, Muralism without Walls: Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros in the United States, 1927–1940 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009), pp. 116–28.

- 55John E. Abbott, letter to Nelson Rockefeller, November 24, 1942. Kirstein, I.D., MoMA Archives.

- 56See Buntinx, “El eslabón perdido,” p. 74.