HISTORICAL DOCUMENT: Originally published in 20-seiki Buyo 5 (20th-century dance), September 1960. Translated into English by Colin Smith

In May of 1960, our group chanced upon an absolutely new experiment in music. It was an improvisational piece of musique concrète, executed collectively.

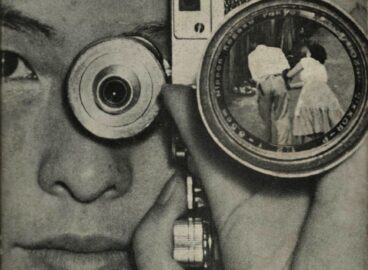

Just before discovering this approach, we had been preparing materials for a tape recording of musique concrète. A variety of sound sources stood before us, including oil drums, washtubs, water pitchers, brooms, plates, coat hangers, metal and wooden dolls, a vacuum cleaner, stones from the game of Go, cups, a radio, an illustrated guide to plants, a wall clock, cello, rubber ball, an alto saxophone, a prepared piano, etc. Once we started the tape rolling, the smorgasbord of sound-producing objects struck us with a bizarre and vivid sonic image. We then began improvising with absolute spontaneity. What followed was a profusion of sounds which usually go unnoticed or are produced only out of necessity during day-to-day life. We lost ourselves in the movements and collisions of the objects, and suddenly we felt as if we had a grasp on the life force of the unconscious, materialized.

After performing this first musical experiment, we immediately noticed that our working method was analogous to the famous definition of Surrealism found in the first Surrealist manifesto: “Pure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.”

Energized by this discovery, we decided to continue experimenting. This led to our second piece, Automatisme No. 1.

I believe our work with musical automatism represented an important departure from previous works of musique concrète for two reasons. First, six of us produced it collectively; and second, we adopted improvisation within the framework of musique concrète, recording the actual sound without any mechanical manipulation so as to maintain the purity of the spontaneous method.

The collective nature of our music was a means of circumventing subjectivity, personal idiosyncrasies, conventional thought patterns, and other residues of humanism that can plague solo attempts at automatism. Like the first work of automatism, Philippe Soupault and Andre Breton’s book Les Champs Magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields), ours was a collaborative effort that sought to draw forth our respective unconscious minds in order to attain a universal automatism, to reach the collective unconscious that, according to Jung, underlies each personal unconscious.

As for our process of pure automatism, it was not merely an improvised musical performance, but rather a spontaneous performance based on a wide range of concrete sounds. It served as a rebuttal of Tono Yoshiaki’s critique of pure automatism as seen in the work of Joan Miró: “A sort of spineless subjectivity seems to pervade his pure automatist works. The weak point of pure automatism is that it is short on rapport with the properties of materials, frequently descending into mere decoration.”

Having arrived at this method of making music, we aspire to show you the objet sonore (sound object) in its true form, in which degrees of transparency and opacity, dampness and hardness reverberate within a storm of immediacy, charged with raw power, and make the concrete music works of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry sound, by comparison, like the pallid song of a nightingale.