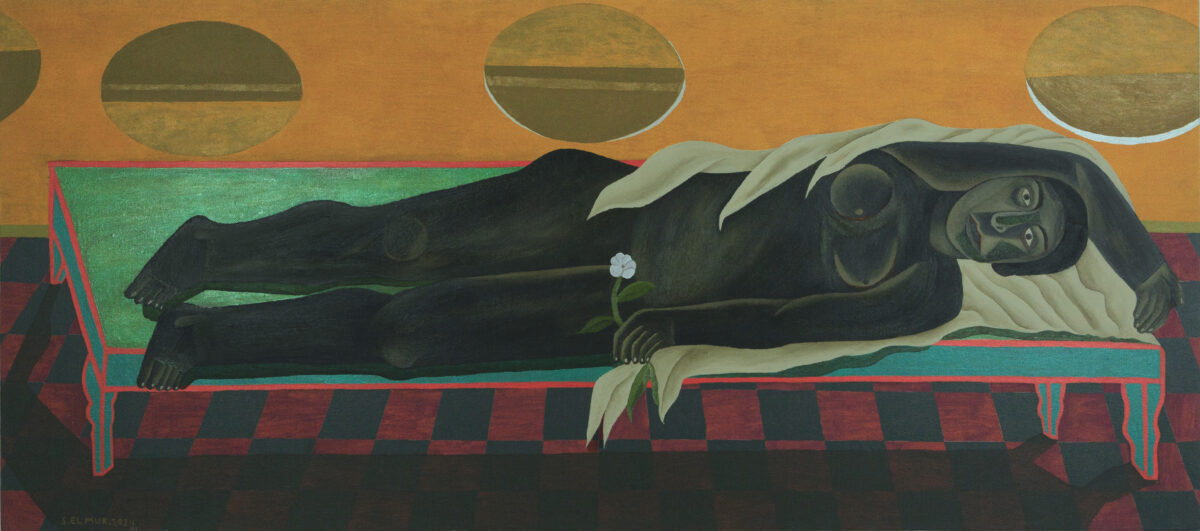

A work of openness and inscrutability, Salah Elmur’s Missing and Lost People’s Day (2021) commemorates a terrible moment in Sudan’s recent history: the massacre on June 3, 2019, when security forces opened fire on a peaceful protest in Khartoum. Hundreds were killed, injured, or arrested. In this painting, which Elmur made during a residency in Accra, Ghana, he pays homage to the family members who continue to look for those who are missing—and to demand accountability from the government. Moreover, he reminds us of the gulf in possibilities between 2019 and 2024; the starting point of a demand for progress is itself now out of reach, as the country suffers through the hunger, internal displacement, and horrific daily violence caused by ongoing civil war.

Missing and Lost People’s Day also points toward the complex and empathetic politics of an artist who has reflected on his homeland for four decades. The painting shows seven protestors—three men, three women, and a child—each dressed in monochrome Sudanese attire. They appear emblematic, though Elmur’s subjects always look half realistic and half like characters in a story. Six of them hold white pieces of paper, each of which contains the image of a missing person. Several cover their own faces with the depicted face, as if it were their own. The effect is evidentiary and stirring, as if each protestor were two people at once—the living and the dead.

It is also a remarkably self-reflexive painting, because photography is at the very heart of Elmur’s practice and, specifically, the inspiration for the works he has been making since his mid-30s, of which Missing and Lost People’s Day is exemplary. Its profound political commitment also reflects the inextricability of art and politics, for better and for worse, in the Sudanese context. Sudan’s modern art history typically begins with the Khartoum School1See Anneka Lenssen, “We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal”—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context,” post: notes on art in a global context, April 4, 2018, https://post.moma.org/we-painted-the-crystal-we-thought-about-the-crystal-the-crystalist-manifesto-khartoum-1976-in-context., which in the postcolonial excitement of the 1960s sought to find and represent a specifically Sudanese identity. When Elmur, who was born in 1966, studied at the College of Fine Art and Applied Art in Khartoum, the lead tutor was Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, cofounder of the Crystalist movement that challenged the foundations of the Khartoum School.(Elmur, under pressure from his family to earn a living, studied graphic design, but he painted in his free time and sought advice from Ishaq and other lecturers.) The Crystalists aimed to break free from art’s ties to nationalism and class and move toward Conceptualist underpinnings, particularly as elaborated through a study of the intrinsic properties of materials. However, as the country’s political situation worsened in the 1980s, many artists fled to Europe or neighboring countries. When Omar al-Bashir seized power in 1989, his repressive regime began instrumentalizing art, pushing artists to produce pastiches of Islamic designs or Sudanese identity. Elmur was targeted by the conservative government. Soon after the coup, the authorities deemed one of his cartoons inflammatory—an image he had drawn for the newspaper and magazine where he worked after university—and he was fired from his job and then arrested. Afterward, he fled to Nairobi, where many Sudanese artists were already living.

When he returned to Khartoum, he painted furiously, developing the style that he is now best known for, with photography at its center. As he often tells the story, after Sudan achieved independence in 1956, the state mandated that each citizen carry an identity card.2Information from a conversation with the artist, June 10, 2024. Suddenly, all of Sudan needed to have their picture taken, and so Elmur’s enterprising father opened a photography studio—the Studio Kamal, which was adjacent to his own father’s barbershop—to meet this demand. As a child, Elmur was fascinated by the rejected photos that were kept in a tin box: double exposures or photographs in which a subject turned a head or arm, leaving a scar of a blur across the picture. These images, as well as others from his archival collection, became the basis for his new paintings. The technological misfires account for some of the glimpses of oddness in his portraiture: the wonky cheeks of one subject’s face, or the second chin that unexpectedly protrudes from another’s. Sometimes the double exposures are easier to spot because a subject appears to have two or three faces, with the extras hiding behind the original like discarded personalities—or, as in Missing and Lost People’s Day, take the form of an image of a face that is held in front of an actual face. These glitches are commensurate with the overall strangeness of Elmur’s work. His figures’ blocklike bodies seem at once too bulbous in their shape and too linear. Subjects are often shown in head-on formality—like they are posing for a studio photographer—or holding animals or plants as if to record their own role as caretakers, occupying the frame with impenetrable or perhaps simply worried facial expressions.

Elmur’s decision to put photography at the core of his work is a loaded one. The photograph played an important role in colonialism, where it reinforced the racist views of the European administrators. Popular images of the time showed “newly discovered” people in tribal dress, submitting them to the taxonomies and hierarchies laid out by colonial authorities. Others showed crowds arrayed as passive subjects around a central European administrator, clearly visible by his white skin and, more often than not, his obstinately white linen attire. (Elmur has also collected examples of these colonial images.) This legacy persists in Elmur’s work, though he also brings out other, less theoretical and arguably more powerful uses of photography: its dual role as a mechanism of state and economic state control (as, for example, in ID cards) and, on the flip side, as a means of accountability or way to contest state control by evidentiary testimony.

His Innocent Prisoners series (2019) refers to those who were disappeared under Omar al-Bashir’s regime. His subjects mostly appear in white, each holding or identified by a number, recalling another genre of photography: the mug shot, examples of which also appear in Elmur’s collection. He has acquired numerous archival photographs of apparent criminals from the United States, with their name, age, alleged crime, and other particulars handwritten underneath profile and frontal views. He also collects mug shots from 19th-century Egypt as well as Egyptian and Sudanese identity cards—much like those produced by the Studio Kamal.3For examples of these images, see Mary Aravanis and Michael Obert, eds., Salah Elmur: Memories from a Tin Box, exh. cat. (Cairo: Concord Press in association with Gallery 1957 and Vigo Gallery), 2023. Other elements of his collection are less typical, such as water and electricity invoices and notices informing recipients that their service will be cut off after 24 hours if the bill is not paid immediately. These latter administrative papers were the inspiration for the Central Electricity and Water Administration series (2022), which shows the artist’s trademark characters standing next to water tanks and towers whose contents they have been denied. Water supply in Sudan is a serious issue, with most in the arid country hugging the contours of the three major rivers. For Elmur, who was raised on the banks of the Blue Nile, the idea of legislating access to water through extortive corporations is no mere infraction but a major example of the injustices of Sudanese corruption.

These notices, much like the images held by the figures in Missing and Lost People’s Day, point to the outsized importance of paperwork (passports, contracts, leases, birth certificates, images) among the migratory and dispossessed. If a house or a life is destroyed, these documents can be key to establishing lines of credit, gaining permission to travel or remain, or securing government benefits, new legal standing, and other fundamental rights. (Or to alerting you that you will have no water or that you must leave the country.) Elmur’s artwork not only acknowledges the power of these papers—the proof of life that the relatives of the June 3 massacre brandish in front of them—but also recognizes the absurdity of this power, couching this proof within a world of surreal and made-up figuration. These documents are both more and less than mere pieces of paper, depending on the authority behind them. But such testimony is sometimes all that people have: fragile leaves of paper that Elmur elevates on his stretched and confrontational canvases.

All personal accounts from Salah Elmur, unless indicated otherwise, were gathered by the author during discussions with the artist in the spring and summer of 2024.

- 1See Anneka Lenssen, “We Painted the Crystal, We Thought About the Crystal”—The Crystalist Manifesto (Khartoum, 1976) in Context,” post: notes on art in a global context, April 4, 2018, https://post.moma.org/we-painted-the-crystal-we-thought-about-the-crystal-the-crystalist-manifesto-khartoum-1976-in-context.

- 2Information from a conversation with the artist, June 10, 2024.

- 3For examples of these images, see Mary Aravanis and Michael Obert, eds., Salah Elmur: Memories from a Tin Box, exh. cat. (Cairo: Concord Press in association with Gallery 1957 and Vigo Gallery), 2023.