Raised during the socialist period of the former Yugoslavia, Irena Lagator Pejović examines two case studies of Yugoslav art and architecture that provide insights into Montenegro’s transition to neoliberalism. From a contemporary post-transitional perspective, the author explores changes in public space and the public sphere through a combined analysis of the history of the SDK building designed by the architect Petar Vulović and a performance by the artist Ilija Šoškić pertaining to institutional critique. This essay emphasizes a relevant issue pertinent to most ex-Yugoslav countries, that is, the particular stage at which a society is when it allows the ethical action of its own cultural heritage to vanish in an attempt to achieve maximum profit in minimum time.

I was born in the 1970s and grew up in Yugoslavia. The socialist education I received there, and the country’s decentralized socialist culture and system were highly formative and influenced in my decision to devote myself to the field of culture. As an art student in the 1990s and during the start of my professional artistic practice in the first decade of the 2000s, I closely followed my country’s transition from socialism to neoliberalism and noticed nuances in the differences between the old and new systems. From the present post-transitional perspective, now that we can observe how the public sphere has changed during times of transition, certain cases of Yugoslav art and architecture deserve a closer analysis. Looking to past examples helps to activate a critical understanding of the present in relation to cultural heritage.

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, which developed as a social project, underwent rapid modernization during the middle of the twentieth century. In this period, architecture was seen as having a relevant social function, as an important common denominator in what was a multiethnic, multicultural, industrialized society, i.e., in a mix of ideological systems. By the mid-1980s, architecture was providing a distinct framework for the functioning of state institutions in every sector of society, including the economy, education, art, and healthcare. Even though the intensive construction being undertaken at this time was funded through foreign loans, Yugoslavia continued to foster concepts of socialist space, utopian idealism, and hybridity that had driven its formation. It seemed that the country was progressing even as evidence of crisis was visible.1Tvrtko Jakovina, Socialism and Modernity: Arts, Culture, Politics, 1950–1974, exh. cat. (Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2012).

Those born between the 1950s and 1980s in Yugoslavia were taught, from elementary school onwards, that their country was a “bridge” between East and West and that Yugoslav culture extended beyond its own borders. During the early 1960s, Yugoslavia had contracted state cultural agreements with nineteen countries, and these were intended as mutual exchanges of art exhibitions, film, concerts, and sport events.2Branka Doknić, Kulturna politika Jugoslavije 1946-1963 (Beograd: Službeni glasnik, 2013), 243. However, with the dissolution of “brotherhood and unity,” a guiding post–World War II concept for the country’s multiethnic society, with the evaporation of so-called communism for the people, or socialism with a human face, and with the parceling of the country in the 1990s, the idea of one bridge has been refracted into that of many smaller ones.

This text draws on two works of art: one architectural and the other performative, i.e. one permanent, that might be described as alternative modernism and the other ephemeral, relating to institutional critique. Both reflect Yugoslav intercultural thought and can be understood as bridges across different disciplines and societies. The utopian Yugoslav experience allowed their creators to think openly and to retain a critical distance from dominant flows. Moreover, their practices show us that words such as “profit” and “time” may have had far more ethical overtones than they do in today’s neoliberal context, in which the concept of social responsibility has the tendency to mutate toward exploitation and exclusion. The first is a building by Petar Vulović (born 1931, Ivanjica),3Petar Vulović was a student of the great mathematician and geometrician Milan Zloković, and also highly esteemed by the Slovenian architect Edvard Ravnikar. He was employed at the National Bank Architectural Bureau (1959–1965). Petar Vulović, interview by Borisav Vukićević, July 10, 2012, copyright © Borislav Vukićević personal archive. an educator and architect who designed and constructed for the future while at once learning from the past, and who made visible the economy as responsibility through architecture. The second is an action by Ilija Šoškič (born 1935, Dečani), an artist and rebel who searched for everyday artistic ethics and the valuation of emotive processes in mundane life, learning from reality and celebrating mental functions and thought processes in his pieces.

Among various institutions that disintegrated after the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s was the SDK, or Služba društvenog knjigovodstva (Social Accounting Service). This independent state institution responsible for the state’s bookkeeping and payment transactions was established in 1962. Among other things, it protected the state and its workers from unexpected debts for which institutions serving the common good (such as health-care or pension funds) might be liable, and that might result in a company’s inability to pay taxes or employee benefits. This kind of inter-institutional control and overarching social responsibility strengthened social well-being and enabled the development of civic institutions of general importance, such as schools, the army, and the police. In many ways, it appeared to be a utopia in operation. Until the 1990s, the SDK functioned in each of the Yugoslav republics. When, in 2002, it was finally closed after several transformations of its original role, the responsibility for handling payment transactions was transferred to the new countries’ commercial banks. With this shift, state tax payments began to lag, an irregularity the tax administration failed to notice until it was too late: The state eventually became unable to properly service pensions, health care, education, and social benefits, and nowadays this is largely financed through the state budget. This problem opened the door to the grey economy and corruption.

Authenticity and Transition

While searching for its own identity between Western modern functionalism and Soviet heterogeneous influences, Yugoslav architecture both countered and shared in politics and ideology. Petar Vulović designed several national banks and SDK buildings.4The urban locations of these buildings all had strategic importance, because they were built in the central parts of cities. Vulović constructed bank buildings in Makarska, Croatia, in 1960–62; in Cetinje, Montenegro, in 1960–1964 at an ex-market on Balšića Pazar; in Koper, Slovenia, in 1965–67; and his key achievements include the SDK in Belgrade in 1969, the filial SDK in Kraljevo in 1973, and the SDK in New Belgrade in 1987. When he was invited to design the national bank in the heart of Cetinje, Montenegro, later transformed into the SDK, he wondered how he could possibly design something to “fit” the town of the writer and philosopher Petar II Petrović Njegoš.5Petar II Petrović Njegoš (1813–1851), was prince-bishop of Montenegro from 1830 to 1851. He was a renowned poet and philosopher whose works are considered to be among the most important in Serbian and Montenegrin literature. He first studied Montenegrin history and literary heritage through Njegoš’s work and also the work of the writer-politician Stefan Mitrov Ljubiša, especially famed for his short stories. In this way—only after he had understood more about the heritage of Montenegro—did he gain the necessary confidence to build there. Ljubiša and Njegoš played vital roles as political, spiritual, and cultural leaders of a society whose complex history and community they interpreted through prose and poetry, and through realism and romanticism based in folk tradition. Another reason to accept the opportunity was the fact that the town’s main urbanist was Bogdan Bogdanović (born 1922, Serbia)6It was an honor for Vulović to be able to work closely with Bogdanović, who was by this time a well-known Yugoslav architect, writer, and professor, whose monuments to the victims and heroes of World War II across Yugoslavia, constructed between the 1950s and the 1980s, represent a hybridization of sculpture, architecture, and landscape. who, in the late 1950s, worked on the first postwar urban plan for Cetinje.

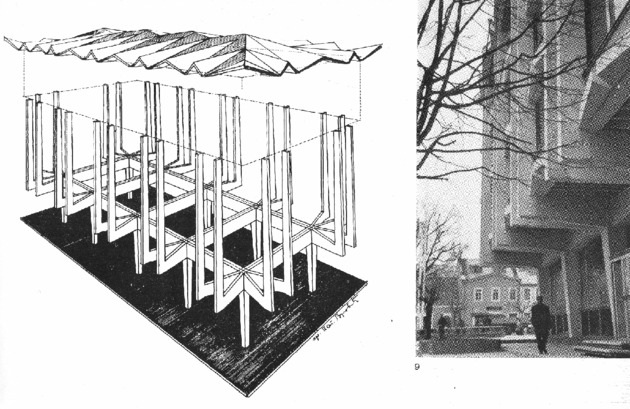

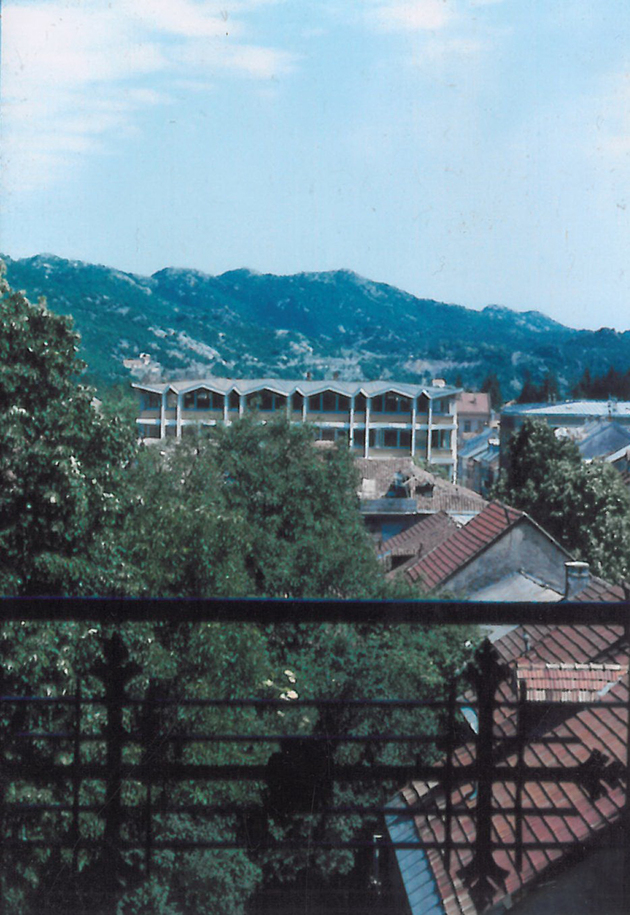

Vulović’s unconventional concept of the bank took into account the urban and historical specificities of the town and natural features of the environment that would surround it. He observed the geometry of the Cetinje valley situated within amorphous hills and reflected that in his plan. The resulting building, in its new, modernistic tone, was also “in dialogue” with existing embassies and palaces in Cetinje. Though mainly designed to serve an economic purpose, Vulović’s building ended up reflecting the larger culture of its time because education, science and culture were understood as interconnected processes necessary for the development of society, which Vulović tried to make visible in his projects. It began with a visually subordinated ground floor7Bogdan Bogdanović envisioned a covered walkway for the town and suggested an arcade to Vulović, but Vulović’s response was a free, cantilevered space. and surrounding colonnade.8The colonnade consisted of multiple series of twin pillars that formed a skeleton-like support for the three upper floors, allowing them to be wider than the ground floor. The architect sees his pillars as his homage to Njegoš’s poetry. Petar Vulović, interview by Borisav Vukićević, July 10, 2012, copyright © Borislav Vukićević personal archive. Together with the rhythmic play of materials and openings along the facade, this composition resulted in extreme clarity of conception: The impression was of a floating but nonetheless monumental object of light and elegant weight despite its concreteness. For Vulović, harmony and proportions were important in their capacity to instil a sense of calmness in the observer. When Bogdanović saw the drawing of the future project, he responded: “That’s it! It grows up! It gives a feeling of large monumentality, lyricism and stability that are difficult to connect.”9Petar Vulović, interview by Borislav Vukićević, July 10, 2012, copyright © Private archive of Borislav Vukićević.

The most remarkable and unique element of this building was its roof, which both evoked traditional Cetinje roof design, steep with two-sided mansards, and echoed the dynamic natural landscape beyond. It consisted of twenty-four small, continual mansards that formed twenty-eight coves. This composition created a linear rhythm of aesthetics that organically and with panoramic clarity communicated with the environment—and furthermore reflected the author’s broad education, which was rooted in Pythagoras, Plato and Euclid, whose theories of symmetry and proportions he integrated.10Petar Vulović’s originality was also reflected in his technical solution within the roof for rainwater drainage. In this aspect, the roof was a distinct polemic between Vulović and the architects Petar Vukotić, Vukota Tupa Vukotić, and Spasoje Krunić. Borislav Vukićević,,,Razgovor sa profesorom Vulovićem. Kako je ljepota zgrade pretvorena u ništavilo,” Vijesti, Art, August 4, 2012, 9. The roof was covered in copper, used at the time only for something intended to last forever, and which the architect knew would oxidize and thus attain a wonderful turquoise green color over time.

It can be argued that Vulović’s national bank building in Cetinje was an unconventional and site-specific piece of modernist architecture, one that managed to achieve originality while at the same time remaining modern. Moreover, Vulović’s historical, spatial, and social concerns, allow the building to be read as a progressive and critical resistance to the dominant tastes of the 1960s.

Understood from an interdisciplinary perspective, the building may also be acknowledged as a distinct work of art in architecture, and symbolic cultural capital for two reasons: it visualized Yugoslav aesthetics and it showed how the local corresponds with the regional—just as the efficiency of the SDK can be seen as utopic within the building’s concreteness, and within a state that was pretending toward utopian goals.

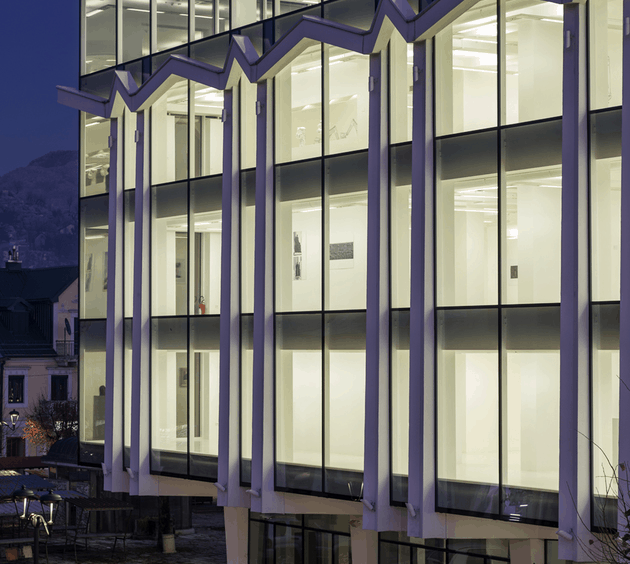

In the transition period in the early twenty-first century, during which time the building was privatized and then sold back to the state, it was reconstructed without the architect’s permission or input, and then inaugurated in 2012 as the Montenegrin Art Gallery of the National Museum. As part of this project, the original roof was removed to add a new floor, and subsequently memorialised by a “line” “attached” to the façade to quote the original roof’s line. The façade, now a glass one, thus generated an interesting paradox: Vulović, in the 1960s, was successfully avoiding the strict modernist aspects of the International Style, rationalization, and glass technology for the sake of creative invention. However, the transitional and postindustrial society11Industrialization in Yugoslavia was based on socialist ideology and the economy and led to a proletariat that was conscious of its class status. In the late 1950s, the industrial giant Obod Cetinje Electrical Industry was launched, and until the late 1980s, it sold high-quality refrigerators, washing machines, and freezers throughout Yugoslavia, becoming a symbol of Yugoslav industrial success. With the breakup of the state during the 1990s and the initiation of the transition from socialism to capitalism, economic ideology and the factory quickly failed, causing a chain reaction that led other Montenegrin factories, including the Košuta shoe factory, the Radoje Dakić tractor factory, and many other factories in each of the Yugoslav republics, to fail. facilitated precisely what the architect had wanted to avoid—the globalized architecture of industrial society—and transmuted Vulović’s aesthetics, structure, and scientific approach into what in essence would be a glass box. When informed about the reconstruction, Vulović commented: “This has nothing to do with my building . . . and has transformed one essential thing into the banal . . . If architecture is an art, and for me it is the number one art, and if this is a gallery of contemporary art, then architecture should have been involved in it, and in its entirety, as it is given.”12Borislav Vukićević,,,Razgovor sa profesorom Vulovićem. Kako je ljepota zgrade pretvorena u ništavilo,” Vijesti, Art, August 4, 2012, 9.

Art and Protection

A similar indifference to cultural politics is taking place in the arts of our small country of Montenegro in coping with the globalized world. In 2018, two glass panels on the reconstructed building’s facade broke into tiny pieces but, magnificently still holding together, they have not been replaced. For anyone familiar with the history of this building, with institutional critique and the neo-avant-garde, this situation brings to mind a work by the Montenegrin artist Ilija Šoškić. Šoškić came of age artistically and intellectually in the 1960s.13Ilija Šoškić’s influences include Jerzy Grotowsky’s poor theater, action painting, French existentialism, Russian experimental theater, and the international leftist student uprisings of 1968, as well as Italian arte povera. See Nebojša Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić—An Artist of Living Images,“ in Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, exh.cat. (Belgrade and Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Arts, Belgrade, and Museum of Contemporary Arts, Novi Sad, 2018), 123. Through his actions and gestures, he critiqued the institutionalized art system and ideology of the time, as well as his own existence. He considers the artistic process in and of itself to be an object and in doing so affirms life beyond profit and greed, just as Vulović’s building was not created to consume the space for the sake of profit but rather for the sake of social responsibility.

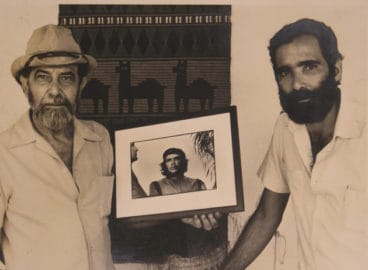

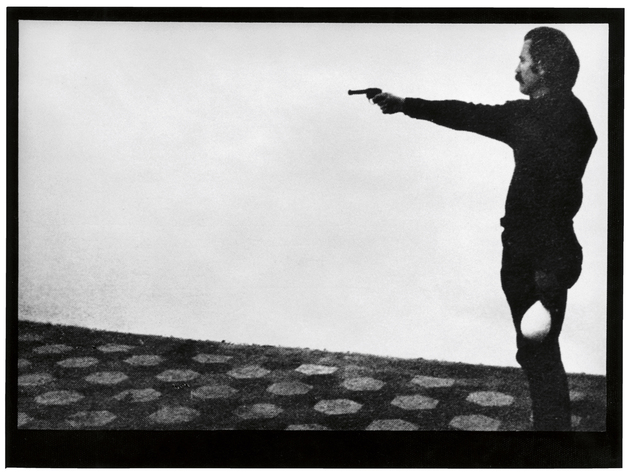

Šoškić fired six shots from a revolver into the wall of the Galleria L´Aticco in Rome in 1975, while dressed in a Red Army uniform and holding milk in his left hand. He called this act Maximum Energy—Minimum Time. As the fourth and final part of a larger action entitled Milk and Silk,14In the first action, Conversation, the artist, while seated on a red cushion, performed a “verbal sculpture” by polemizing with the audience. In the minimalist second action, Controversy, he first determined the central point of a wall using an imaginary crossing of diagonals and then he stuck a knife into the center of their imagined intersection. In the third action, Armwrestling, he sat at a black table and played chess with the American artist John Ratner. Petar Ćuković, “Zygote,” in Pavilion of Montenegro Presents “The Fridge Factory and Clear Waters,” exh. cat. (Podgorica, Montenegro: Contemporary Art Centre, 2011), 83. this work was dedicated to the poet Vladimir Mayakovski, who decided to commit suicide. A poet devoted to social poetry and the avant-garde, Mayakovski (1893–1930) placed his work in the service of the October Revolution of 1917.15According to the Croatian literary theorist and essayist Aleksandar Flaker, Mayakovski was a revolutionary poet—a poet of movement, action, catastrophes and convulsions, a propagandist, and an apologist for the October Revolution—who believed in the power of collective work. See also Vladimir Mayakovski, Poeme i stihovi(Sarajevo: Veselin Maselša, 1983). Šoškić decided to celebrate life16The reason for this act, as Šoškić explained to the art historian Petar Ćuković, could also be traced to a 1970s street fight in Rome between left- and right-wing sympathizers, which occurred daily, when one of them pointed a gun at Šoškić and he experienced a moment of potential maximum energy in minimal time. Petar Ćuković, oral communication with the author, October 16, 2018. through the evocation of death, to glorify the force of the mind and thinking through the notion of speed and the creation of the zygote,17Ćuković, “Zygote,” 78. with which he alludes to a new kind of being or organism. Could Vulović’s building have become a space for this new synthesis of ethics, education, and critique if its values had been used within the cultural sector as opposed to their distinct separation in neoliberal times?

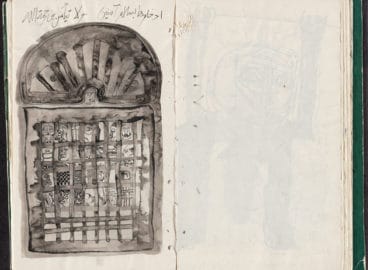

The presence of a bottle of milk in the artist’s left hand can be looked upon as a celebration of life, because mother’s milk is the first substance we are fed after being born, and also the semantic potential of the whole act, including the bullet planned for a gallery wall. While the celebration of life had already been seen in concrete form in Vulović’s references to the variety in the Cetinje rooftops and to the landscape beyond, it is demonstrated in a more ephemeral form in Šoškić’s work. Šoškić understood that capitalist financial mechanisms are capable of transforming socialist values—and that even art won’t be bypassed by the shift—and he chose two essential elements for his reflection: a wall as concrete and static element and the speed of a bullet as ephemerality. Vulović’s touted modernist walls became during the period of transition merely industrial relics with two glass panels broken. Šoškić, then, was obviously prescient in symbolically piercing a wall to point at art’s transformative potential and energy, at the protective, educational, and emancipatory role of art back in the 1970s, before the consumeristic logic of capitalism would start to exploit it. Related to this idea, another of his works becomes relevant—one of his verbal paintings18Ćuković, “Zygote,” 82. from 1974, on which he wrote and counted down all the elements needed for the castration of a bull and that he hung at the entrance of the Porta Portese in Rome. He shows us literally how to strip the bull (or capitalism) of the ability to reproduce, and he does so in a public space.

Šoškić’s tactical approach of continual shifting in relation to one’s surroundings teaches us about the necessity for permanent critical distance. And that same critical distance is what urged Vulović to incorporate the surroundings, history, and poetics of Cetinje into the literal concreteness of his distance from dominant flows. Within the context of contemporary global vocabularies, that critical distance has become necessary in the visibility and understanding of hyper-local contexts. Then art becomes a “bridge” between distant times, or, in the case of this analysis, between modernism and post-transition in states that were once thought to bridge the unbridgeable, like the East and West in the case of Yugoslav self-perception, and in states that allowed transition to erase its legacies.

Now that the bank has become a space for exhibiting art, what is inevitable is to question culture as a construct in small states competing with big ones in global times when art has become a new currency. What was once a symbol of economic stability is, today, an art space. In this shift, the building has forfeited the role of the “new organism,” or the celebration of life to which Šoškić tried to direct us, even if all the predispositions to such a role were already incorporated by Vulović.

From a post-transitional perspective, it becomes obvious from the discursive chain of events, that Vulović’s building has become an object of neoliberal consumption—even if presently it is part of a museum cluster. Such loss in terms of spatiotemporal reciprocity, memory, knowledge, and aesthetics is, therefore, today more costly than the expensive conversion of the building. If art and architecture intervene anthropologically in the everyday life of humans, without being denied the capability to remain open to new users in new times, I wonder what an aesthetic symbol Vulović’s building would have become had its authenticity been preserved—and what Šoškić’s tactics might teach us if integrated within the local artistic context. Around 2010, the building was slated to become a space for exhibiting art, though without any regard for Vulović’s initial artistic intentions for the building. But exhibiting art requires art’s constant and careful archeology, including architecture as art and as space.

The issue of profit then becomes visible, because profit gained in transition seems to differ from profit gained over the long term, especially where art is concerned. Though the majority of the global experience economy is based on cultural tourism, in small transitional states, the evaporation of cultural heritage is pervasive. Vulović’s building was not the only building to vanish permanently from the Montenegrin modernist map. If once we were proud of our self-managing socialism, during which time this postwar architecture was produced, today we are helpless in our vanishing modernism.19Up to now, we can identify the following disappeared, modified, or displaced modernist buildings or institutions: the National Bank by Petar Vulović in Cetinje; Hotel Crna Gora by Dragiša Brašovan but attributed (wrongly according to Borisav Vukićević) to Vujadin Popović in Podgorica; Kino kultura in Podgorica; Moderna galerija in Podgorica (renamed, removed); Hotel Podgorca by Svetlana Kana Radević, and the Public Library by Milan Popović in Budva (Zeta film), to mention but a few. And last but not least, currently, students of architecture are writing a petition against demolition of the Beko building by Božidar Milić in the heart of Podgorica.

We can ask what stage a society is at when it allows the ethical action of its own cultural heritage to vanish in its attempt to achieve maximum profit in minimum time. That is why this essay brings critical attention to the intersection between the economy and art, to provide a more relevant understanding of the present and teach us not to continue the politics of indifference at a time when the size of countries is made irrelevant. It shows how one small state in periods of transition has tried to cope with large currents in the globalized biopolitical world and how, had the educational, scientific, and cultural aspects of their achievements and time been highlighted, things could have been different.

- 1Tvrtko Jakovina, Socialism and Modernity: Arts, Culture, Politics, 1950–1974, exh. cat. (Zagreb: Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, 2012).

- 2Branka Doknić, Kulturna politika Jugoslavije 1946-1963 (Beograd: Službeni glasnik, 2013), 243.

- 3Petar Vulović was a student of the great mathematician and geometrician Milan Zloković, and also highly esteemed by the Slovenian architect Edvard Ravnikar. He was employed at the National Bank Architectural Bureau (1959–1965). Petar Vulović, interview by Borisav Vukićević, July 10, 2012, copyright © Borislav Vukićević personal archive.

- 4The urban locations of these buildings all had strategic importance, because they were built in the central parts of cities. Vulović constructed bank buildings in Makarska, Croatia, in 1960–62; in Cetinje, Montenegro, in 1960–1964 at an ex-market on Balšića Pazar; in Koper, Slovenia, in 1965–67; and his key achievements include the SDK in Belgrade in 1969, the filial SDK in Kraljevo in 1973, and the SDK in New Belgrade in 1987.

- 5Petar II Petrović Njegoš (1813–1851), was prince-bishop of Montenegro from 1830 to 1851. He was a renowned poet and philosopher whose works are considered to be among the most important in Serbian and Montenegrin literature.

- 6It was an honor for Vulović to be able to work closely with Bogdanović, who was by this time a well-known Yugoslav architect, writer, and professor, whose monuments to the victims and heroes of World War II across Yugoslavia, constructed between the 1950s and the 1980s, represent a hybridization of sculpture, architecture, and landscape.

- 7Bogdan Bogdanović envisioned a covered walkway for the town and suggested an arcade to Vulović, but Vulović’s response was a free, cantilevered space.

- 8The colonnade consisted of multiple series of twin pillars that formed a skeleton-like support for the three upper floors, allowing them to be wider than the ground floor. The architect sees his pillars as his homage to Njegoš’s poetry. Petar Vulović, interview by Borisav Vukićević, July 10, 2012, copyright © Borislav Vukićević personal archive.

- 9Petar Vulović, interview by Borislav Vukićević, July 10, 2012, copyright © Private archive of Borislav Vukićević.

- 10Petar Vulović’s originality was also reflected in his technical solution within the roof for rainwater drainage. In this aspect, the roof was a distinct polemic between Vulović and the architects Petar Vukotić, Vukota Tupa Vukotić, and Spasoje Krunić. Borislav Vukićević,,,Razgovor sa profesorom Vulovićem. Kako je ljepota zgrade pretvorena u ništavilo,” Vijesti, Art, August 4, 2012, 9.

- 11Industrialization in Yugoslavia was based on socialist ideology and the economy and led to a proletariat that was conscious of its class status. In the late 1950s, the industrial giant Obod Cetinje Electrical Industry was launched, and until the late 1980s, it sold high-quality refrigerators, washing machines, and freezers throughout Yugoslavia, becoming a symbol of Yugoslav industrial success. With the breakup of the state during the 1990s and the initiation of the transition from socialism to capitalism, economic ideology and the factory quickly failed, causing a chain reaction that led other Montenegrin factories, including the Košuta shoe factory, the Radoje Dakić tractor factory, and many other factories in each of the Yugoslav republics, to fail.

- 12Borislav Vukićević,,,Razgovor sa profesorom Vulovićem. Kako je ljepota zgrade pretvorena u ništavilo,” Vijesti, Art, August 4, 2012, 9.

- 13Ilija Šoškić’s influences include Jerzy Grotowsky’s poor theater, action painting, French existentialism, Russian experimental theater, and the international leftist student uprisings of 1968, as well as Italian arte povera. See Nebojša Milenković, “Ilija Šoškić—An Artist of Living Images,“ in Ilija Šoškić: Action Forms, exh.cat. (Belgrade and Novi Sad: Museum of Contemporary Arts, Belgrade, and Museum of Contemporary Arts, Novi Sad, 2018), 123.

- 14In the first action, Conversation, the artist, while seated on a red cushion, performed a “verbal sculpture” by polemizing with the audience. In the minimalist second action, Controversy, he first determined the central point of a wall using an imaginary crossing of diagonals and then he stuck a knife into the center of their imagined intersection. In the third action, Armwrestling, he sat at a black table and played chess with the American artist John Ratner. Petar Ćuković, “Zygote,” in Pavilion of Montenegro Presents “The Fridge Factory and Clear Waters,” exh. cat. (Podgorica, Montenegro: Contemporary Art Centre, 2011), 83.

- 15According to the Croatian literary theorist and essayist Aleksandar Flaker, Mayakovski was a revolutionary poet—a poet of movement, action, catastrophes and convulsions, a propagandist, and an apologist for the October Revolution—who believed in the power of collective work. See also Vladimir Mayakovski, Poeme i stihovi(Sarajevo: Veselin Maselša, 1983).

- 16The reason for this act, as Šoškić explained to the art historian Petar Ćuković, could also be traced to a 1970s street fight in Rome between left- and right-wing sympathizers, which occurred daily, when one of them pointed a gun at Šoškić and he experienced a moment of potential maximum energy in minimal time. Petar Ćuković, oral communication with the author, October 16, 2018.

- 17Ćuković, “Zygote,” 78.

- 18Ćuković, “Zygote,” 82.

- 19Up to now, we can identify the following disappeared, modified, or displaced modernist buildings or institutions: the National Bank by Petar Vulović in Cetinje; Hotel Crna Gora by Dragiša Brašovan but attributed (wrongly according to Borisav Vukićević) to Vujadin Popović in Podgorica; Kino kultura in Podgorica; Moderna galerija in Podgorica (renamed, removed); Hotel Podgorca by Svetlana Kana Radević, and the Public Library by Milan Popović in Budva (Zeta film), to mention but a few. And last but not least, currently, students of architecture are writing a petition against demolition of the Beko building by Božidar Milić in the heart of Podgorica.