Addressing the history and impact of violence in Colombia, Juan Manuel Echavarría’s work does not represent violence as an abstraction but rather registers a tangible reality with a name and a face. In an accumulated conflict like this one, victims can come to act on “inherited hatred,” blurring the distinction between victim and perpetrator.

The relationship between art and conflict is not only narrow but also unrelenting throughout Colombian history. From the mid-twentieth century, with the partisan war between the Liberal and Conservative parties, through the guerrilla insurgency in the sixties, to the drug-trafficking violence and the emergence and consolidation of paramilitary groups in the eighties and beyond, Colombia has not experienced a period of relative peace. It must be added that this violent history is superlative. From the period known as La Violencia (1948–58),1Between 1948 and 1958, an undeclared civil war broke out between Liberals and Conservatives, leaving about 300,000 dead, mainly in rural areas. At this time, peasants across the nation were expelled from their lands by prominent landowners due to the lack of effective agrarian reform, and several guerrilla groups were formed and consolidated. With the seizure of power by General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in 1953, tension in the country decreased a bit, until 1957, when a truce was declared between the Liberal and Conservative party leaders. This would lead to the implementation of the National Front in which power was alternated between the two parties for 16 years. the following methods of dismemberment and theatricalization of murder have been described: corte de franela (T-shirt cut), a cut in the base of the neck; corte de corbata (Colombian necktie), a slash under the lower jawbone through which the tongue is pulled out; and corte de florero (flower vase cut), in which the arms and legs are put in place of the head, in a sort of sinister “flower arrangement.”2Germán Guzmán, Orlando Fals-Borda, and Eduardo Umaña Luna, La violencia en Colombia: Estudio de un proceso social (Violence in Colombia: Study of a Social Process; Bogotá: Punta de Lanza, 1977), 1.

In fact, one of the first works by Juan Manuel Echavarría (born 1947, Medellín) refers to the extreme cruelty of the violence in Colombian history. Corte de florero (Flower Cut Vase, 1997) is a series of thirty-two photographs evoking a repertoire of atrocious practices. Nevertheless, a kind of detour opens up through these images, which are not illustrations of cruelty, but rather metaphors built on cross-referenced historical accounts of the national narrative. These references include Mutis’ botanical expedition,3The Royal Botanical Expedition of the New Kingdom of New Granada (1783–1816) was undertaken by the naturalist José Celestino Mutis. Approved during the reign of Carlos III of Spain, the expedition led to the inventory and classification of 20,000 plant species and 7,000 animals. Mutis’ disciples, supporters of Colombian independence, were military and civilian heroes, as well as martyrs of the Colombian independence war. The members of the Botanical Expedition formed an influential Grenadian core, which irradiated revolutionary ideas throughout the country. which constitutes the “propitiatory” object that made the planning of the Cry of Independence (Llorente’s vase)4Llorente’s flower vase symbolizes an episode in Colombian history that occurred in the Main Square of Santa Fe (Colonial name for Bogotá) on the morning of July 20, 1810. When the Spanish merchant José González Llorente refused to lend a vase to the Creole Luis de Rubio, the Creoles responded by accusing Llorente of insulting them, which incited a popular revolt against the Spaniards that caused the fall of the viceroy of New Granada and the formation of a local government. These events mark the beginning of Columbia’s struggle for independence. possible—as well as national pride in the country’s floral diversity—and, of course, the despicable practice of dismemberment known as corte de florero. However, in Echavarría’s photographs, flowers are not flowers, but instead arrangements of human bones that resemble botanical classifications of floral species, each of which has been given a Latin name. What the artist suggests with this series is that the national flower is not the Cattleya Trianae (lirio de mayo, or May lily), but rather the Cattleya Cruenta or Anthurium Mutilatum—the harvest of death blending in a sinister way with the landscape.5This statement is specifically linked to Violencia (Violence, 1962) by Alejandro Obregón, an emblematic modernist work referenced later in this text. Obregón’s painting suggests the figure of a pregnant woman who, lying wounded on her back, blends with the landscape. The author’s statement is a metaphor in relation to the practice of death, normalized by violence, and its later embellishment in modern art.

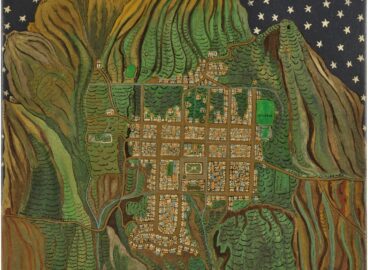

This relationship between landscape and violence is persistent in Colombian art—in works such as La cosecha de los violentos (The Harvest of the Violent Ones, 1968) by Alfonso Quijano; Piel al sol (Skin to the Sun, 1963) by Luis Angel Rengifo; and Violencia (Violence, 1962) by Alejandro Obregón. The scenes depicted in these works, which seem distant and allegorical, are in truth close and real; in fact, they could represent more contemporary massacres, such as the one that occurred in El Salado (2000): “Ropes were used for strangling, a woman was impaled… ears were cut . . . a pregnant woman was murdered and victims were slaughtered.”6“The Report of the El Salado Massacre,”El Espectador, September 14, 2009. In Colombia, entire territories have been named for the violence that occurred within them: the Mapiripán Massacre (1997), Ciénaga Massacre (1998), Curamaní Massacre (1999), Tibú Massacre (1999), Yolombó Massacre (1999), El Salado Massacre (2000), El Chengue Massacre (2001), El Naya Massacre (2001), and Corinto Massacre (2001). There have been 1,982 massacres between 1958 and 2012, with 11,751 victims. Although evil practices persist in the same ways, the artistic treatment of them has been transformed. One of the changes is visible in the relationship that artists have begun to build with the victims of armed conflict. When violence is an abstraction, artists have license to describe its victims with formal preciosity, or to attack and transgress a figure through to disfigurement. When horror remains distant, and the victim has no name or face, experimenting with the representation of a tortured body becomes possible. If in past decades this kind of representation seemed effective (since the aim was to move society by representing the suffering of victims), today such formulas have been exhausted. As an example, Echavarría metaphorizes the corte de florero by diverting its direct reference to mutilation. But, in addition, in Echavarría’s work, there is a significant turn, a shift from the metaphorical to the real, as happens in the video Bocas de Ceniza (Mouths of Ash, 2003–2004).

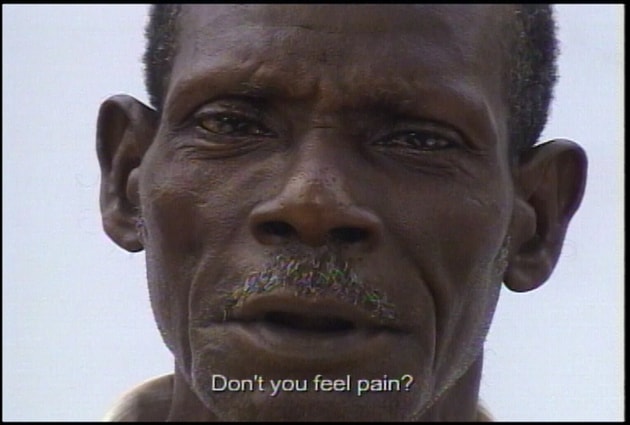

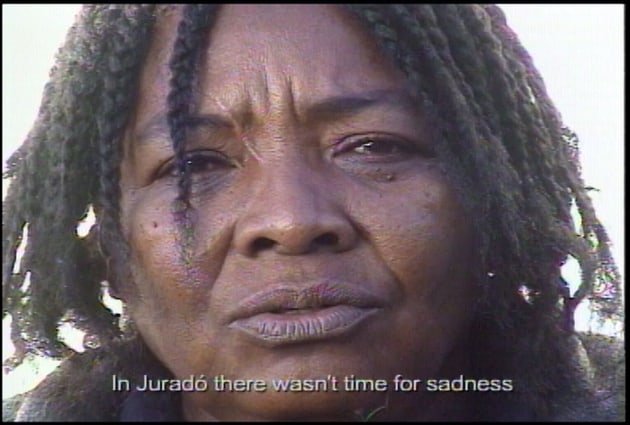

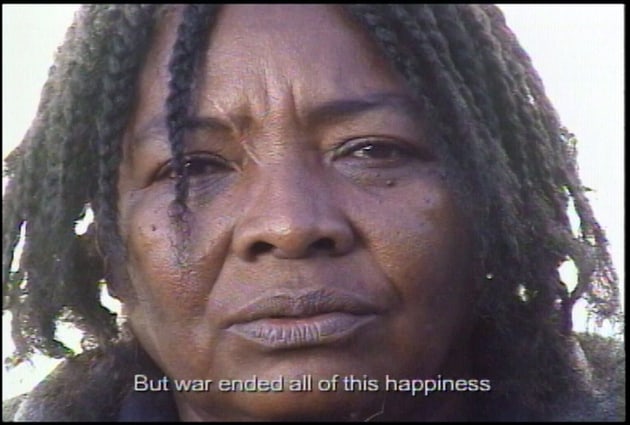

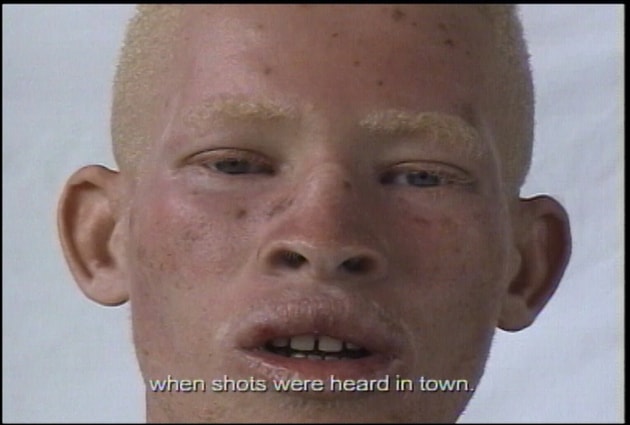

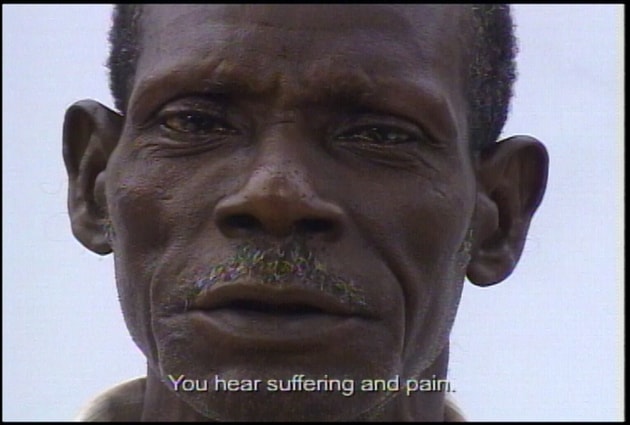

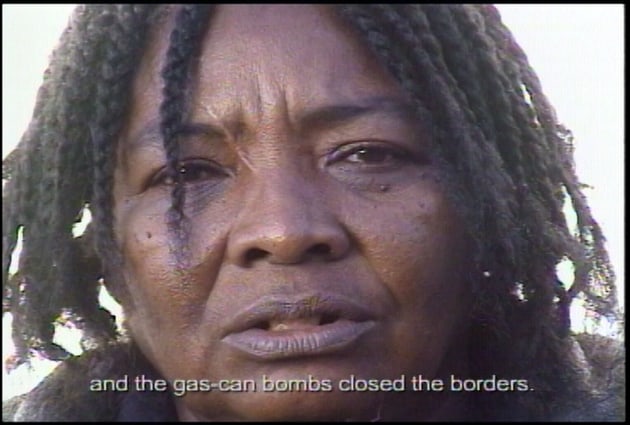

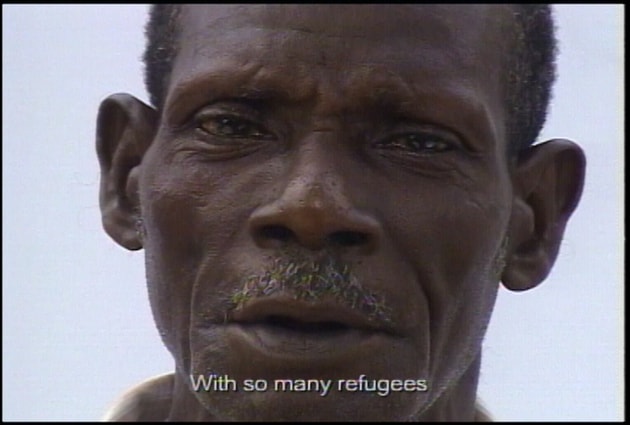

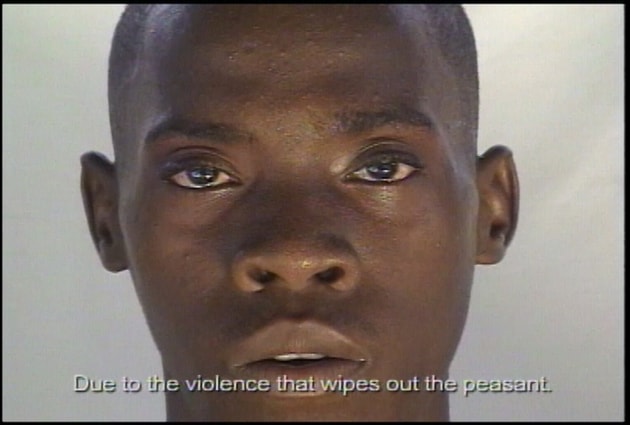

First, it should be pointed out that “Bocas de Ceniza” is a geographical reference. It marks the location where the Magdalena River meets the Caribbean Sea, bodies of water that when encountering each other, leave an extensive ash trail. The river has been central to the economic and political history of the country; sadly, it has also been central to the expansion of the armed conflict, serving as a strategic space that armed groups came to control until they turned its currents into a mass grave, in which the bodies of murdered people are thrown. This practice is documented by Echavarría in the work Requiem NN (2006–15).7The rescued corpses of people killed and thrown into the Magdalena River are deposited in the cemetery of Puerto Berrío, Antioquia. For years, the inhabitants of Puerto Berrío have “adopted” and named the bodies of these unidentified victims, known as NNs (No Names). When choosing an NN, the adopter commits to care for him/her and to pray for his/her soul. In exchange for such care, he/she asks the victim’s soul for protection and favors. Requiem NN is made up of three works: a photographic series (2006–15), a series of 12 videos titled Novenarios en espera (Nine-Day Period on Hold, 2012), and a 70-minute documentary (2013). See Elkin Rubiano, “Réquiem NN de Juan Manuel Echavarría: Entre lo evidente, lo sugestivo y lo reprimido” (“Requiem NN by Juan Manuel Echavarría: In Between the Obvious, the Suggestive and the Repressed”), Cuadernos de Música, Artes Visuales y Artes Escénicas 12, no. 1 (January–June 2017), https://www.academia.edu/31970243/R%C3%A9qu In Bocas de Ceniza, territory is expressed in the voices of the singers: Bella Vista, Bojayá, Juradó, Atrato. The accounts given in their songs were written down and shared by witnesses to and survivors of specific massacres, as the one that occurred in Trojas de Cataca in 2000 or in Bojayá in 2002. In addition to the encounter of dissimilar logics―such as listening to painful testimonies in rhythms more associated with party and joy, or meeting the penetrating gazes of the close-up faces whose strength and fragility demand shock and attention, while affecting us—it is necessary to highlight the process Echavarría undertook in order to make this video (as well as the other works that will be mentioned later).

When artists walk through territories marked by the armed conflict and establish relationships with the communities within them, the victims cease to be a distant notion. This proximity fosters an understanding through political activation and the building of solidarity. In Mouths of Ash, the witnesses and survivors have active voices that narrate barbarism: from their mouths, the ashes spout. When walking through conflict zones, Echavarría finds songs that are testimonies of the massacres that occurred there. In this sense, the artist’s centrality has shifted to the victims—towards the search of their voices, in order to listen to them and to confer legitimacy to their statements in a context in which murders and massacres have long been denied by their perpetrators. Moreover, the compilation of songs in this video offers an account of the oral and musical traditions of two specific regions: the juglares vallenatos (vallenato troubadours) of the Atlantic coast (the songs of Nacer and Dorismel, two brothers) and the music of African origin in the Pacific (the songs of Rafael, Luzmila and Domingo).

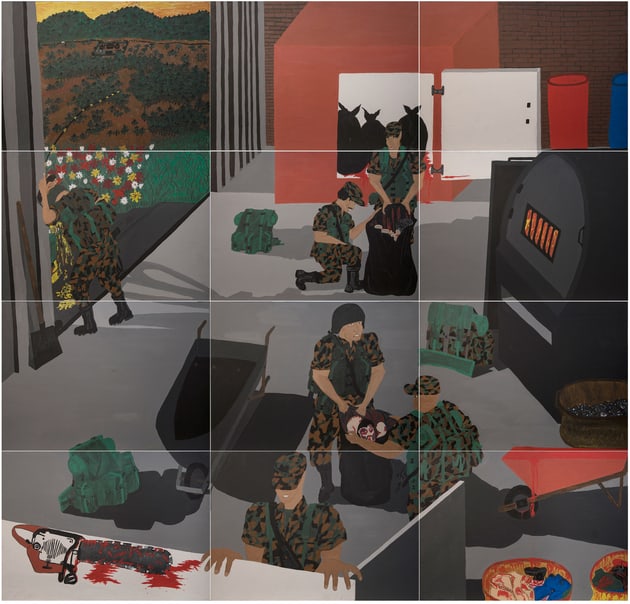

To walk the territories of the armed conflict is “to know with your own feet,” says Echavarría, who learns while walking.8Juan Manuel Echavarría, interview by Elkin Rubiano (phonographic record), Bogotá, October 20, 2015. One of the things he has come to realize is the importance of looking beyond the victim/victimizer or friend/enemy relationship. In a prolonged war of several decades, the boundaries have blurred, and it is not uncommon for the victim to become the victimizer, to act on “inherited hatred.”9In Colombian history, inherited hatreds have long served to promote the political violence embodied in the figure of the avenger: “It’s not easy to quantify hate. It’s not easy to know how many are those who hate, to measure the intensity of their hatred, or to establish how hate and war feed each other. I assume, however, and in general, that the greater the number of victims left by the war, and the greater the injustice associated with the victimization processes, the greater the accumulation of hatred in society as well. I also assume that unregulated wars . . . produce more hatred and increase the conditions for the proliferation of avengers and retaliations, than regulated wars. In that sense, Colombian war, especially in terms of unregulated and highly degraded confrontation between guerrillas and paramilitaries, constitutes a widely inhabited space, if not governed, by vindictive hatred and retarding rage.” Iván Orozco, “La postguerra Colombiana: Divagaciones sobre la venganza, la justicia y la reconciliación” (“The Colombian Postwar Period: Ramblings about Revenge, Justice and Reconciliation”), Working Paper #306, May 2003 (Indiana: Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame Press, 2003), 9. One way to overcome this hatred is by understanding the gray areas of the conflict, that is to give place to the “inherited pains” residing in both victims and perpetrators of atrocious acts, something that Echavarría has explored in such works as La guerra que no hemos visto: un proyecto de memoria histórica (The War We Have Not Seen: A Project of Historical Memory, 2007–2009)10The War We Have Not Seen was made through painting workshops involving 17 former members of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia [AUC]), 44 former members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia [FARC]), one former member of The National Liberation Army (Ejercito de Liberación Nacional [ELN]), and 18 former National Army soldiers wounded in combat. Together these ex-combatants produced more than 400 paintings, 90 of which were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá (MAMBO) in 2009. Each workshop consisted of approximately 25 participants, who had swelled the ranks of guerilla and paramilitary organizations, or the National Army, for periods of 3, 5, 10, and even 16 years. See Elkin Rubiano, “‘La guerra que no hemos visto’ y la activación del habla” (“‘La guerra que no hemos visto’ and the Activation of Speech,” Estudios de filosofía, no. 58 (2018): 65–98, https://www.academia.edu/37192241/Laguerraquen or De qué sirve una taza (What Is the Use of a Cup?, 2014– ),11For this photographic series Echavarría and Grisalez walked a territory that was once the domain of the FARC, whose camps were bombed and taken by the National Army in August, 2007. Almost a decade later, between land and litter, the artists found traces of the bombed camps and vestiges of the assault, such as bullet casings; but they also found boots, a pot, a cup, a cassette, a bra, etc., that is, the tools essential to everyday life. See Elkin Rubiano, “Rios y silencios by Juan Manuel Echavarría,” H-ART. Magazine of History, Theory and Art Criticism, no. 3 (2018): 315–23, https://www.academia.edu/37136012/R%C3%ADosy which he made in collaboration with Fernando Grisalez. In both works, the testimonies of the perpetrators are displayed, since, as the victims, they too are memory holders, and their speech must be activated in order to fully reconstruct the recent history of violence in Colombia. Walking through conflict territories allows the artist to establish close and lasting relationships with the communities within them. Through this practice of listening to the testimonies of victims, a transition occurs. The victims are no longer simply represented, but rather an active presence, as is the case in Mouths of Ash. Works such as this serve to build a speech activation device. The artist does not express himself in the name of the victims, nor does he represent them; rather, he constructs a place where their testimonies can be seen and heard. In this way, his process becomes inseparable from the construction of memory of the armed conflict, and also from the emergence of empathy in the public toward the faces that look straight at us while singing of barbarism. To mourn these losses as if they were our own is the historical debt of a nation that has been unable to elaborate a collective grief. Works such as Mouths of Ash express the possibilities of art in contexts of extreme violence: the activation of the victims’ speech and a settling of the symbolic debts owed to the dead.

Translated by Victoria Lucena Góez

- 1Between 1948 and 1958, an undeclared civil war broke out between Liberals and Conservatives, leaving about 300,000 dead, mainly in rural areas. At this time, peasants across the nation were expelled from their lands by prominent landowners due to the lack of effective agrarian reform, and several guerrilla groups were formed and consolidated. With the seizure of power by General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in 1953, tension in the country decreased a bit, until 1957, when a truce was declared between the Liberal and Conservative party leaders. This would lead to the implementation of the National Front in which power was alternated between the two parties for 16 years.

- 2Germán Guzmán, Orlando Fals-Borda, and Eduardo Umaña Luna, La violencia en Colombia: Estudio de un proceso social (Violence in Colombia: Study of a Social Process; Bogotá: Punta de Lanza, 1977), 1.

- 3The Royal Botanical Expedition of the New Kingdom of New Granada (1783–1816) was undertaken by the naturalist José Celestino Mutis. Approved during the reign of Carlos III of Spain, the expedition led to the inventory and classification of 20,000 plant species and 7,000 animals. Mutis’ disciples, supporters of Colombian independence, were military and civilian heroes, as well as martyrs of the Colombian independence war. The members of the Botanical Expedition formed an influential Grenadian core, which irradiated revolutionary ideas throughout the country.

- 4Llorente’s flower vase symbolizes an episode in Colombian history that occurred in the Main Square of Santa Fe (Colonial name for Bogotá) on the morning of July 20, 1810. When the Spanish merchant José González Llorente refused to lend a vase to the Creole Luis de Rubio, the Creoles responded by accusing Llorente of insulting them, which incited a popular revolt against the Spaniards that caused the fall of the viceroy of New Granada and the formation of a local government. These events mark the beginning of Columbia’s struggle for independence.

- 5This statement is specifically linked to Violencia (Violence, 1962) by Alejandro Obregón, an emblematic modernist work referenced later in this text. Obregón’s painting suggests the figure of a pregnant woman who, lying wounded on her back, blends with the landscape. The author’s statement is a metaphor in relation to the practice of death, normalized by violence, and its later embellishment in modern art.

- 6“The Report of the El Salado Massacre,”El Espectador, September 14, 2009. In Colombia, entire territories have been named for the violence that occurred within them: the Mapiripán Massacre (1997), Ciénaga Massacre (1998), Curamaní Massacre (1999), Tibú Massacre (1999), Yolombó Massacre (1999), El Salado Massacre (2000), El Chengue Massacre (2001), El Naya Massacre (2001), and Corinto Massacre (2001). There have been 1,982 massacres between 1958 and 2012, with 11,751 victims.

- 7The rescued corpses of people killed and thrown into the Magdalena River are deposited in the cemetery of Puerto Berrío, Antioquia. For years, the inhabitants of Puerto Berrío have “adopted” and named the bodies of these unidentified victims, known as NNs (No Names). When choosing an NN, the adopter commits to care for him/her and to pray for his/her soul. In exchange for such care, he/she asks the victim’s soul for protection and favors. Requiem NN is made up of three works: a photographic series (2006–15), a series of 12 videos titled Novenarios en espera (Nine-Day Period on Hold, 2012), and a 70-minute documentary (2013). See Elkin Rubiano, “Réquiem NN de Juan Manuel Echavarría: Entre lo evidente, lo sugestivo y lo reprimido” (“Requiem NN by Juan Manuel Echavarría: In Between the Obvious, the Suggestive and the Repressed”), Cuadernos de Música, Artes Visuales y Artes Escénicas 12, no. 1 (January–June 2017), https://www.academia.edu/31970243/R%C3%A9qu

- 8Juan Manuel Echavarría, interview by Elkin Rubiano (phonographic record), Bogotá, October 20, 2015.

- 9In Colombian history, inherited hatreds have long served to promote the political violence embodied in the figure of the avenger: “It’s not easy to quantify hate. It’s not easy to know how many are those who hate, to measure the intensity of their hatred, or to establish how hate and war feed each other. I assume, however, and in general, that the greater the number of victims left by the war, and the greater the injustice associated with the victimization processes, the greater the accumulation of hatred in society as well. I also assume that unregulated wars . . . produce more hatred and increase the conditions for the proliferation of avengers and retaliations, than regulated wars. In that sense, Colombian war, especially in terms of unregulated and highly degraded confrontation between guerrillas and paramilitaries, constitutes a widely inhabited space, if not governed, by vindictive hatred and retarding rage.” Iván Orozco, “La postguerra Colombiana: Divagaciones sobre la venganza, la justicia y la reconciliación” (“The Colombian Postwar Period: Ramblings about Revenge, Justice and Reconciliation”), Working Paper #306, May 2003 (Indiana: Kellogg Institute, University of Notre Dame Press, 2003), 9.

- 10The War We Have Not Seen was made through painting workshops involving 17 former members of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia [AUC]), 44 former members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia [FARC]), one former member of The National Liberation Army (Ejercito de Liberación Nacional [ELN]), and 18 former National Army soldiers wounded in combat. Together these ex-combatants produced more than 400 paintings, 90 of which were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in Bogotá (MAMBO) in 2009. Each workshop consisted of approximately 25 participants, who had swelled the ranks of guerilla and paramilitary organizations, or the National Army, for periods of 3, 5, 10, and even 16 years. See Elkin Rubiano, “‘La guerra que no hemos visto’ y la activación del habla” (“‘La guerra que no hemos visto’ and the Activation of Speech,” Estudios de filosofía, no. 58 (2018): 65–98, https://www.academia.edu/37192241/Laguerraquen

- 11For this photographic series Echavarría and Grisalez walked a territory that was once the domain of the FARC, whose camps were bombed and taken by the National Army in August, 2007. Almost a decade later, between land and litter, the artists found traces of the bombed camps and vestiges of the assault, such as bullet casings; but they also found boots, a pot, a cup, a cassette, a bra, etc., that is, the tools essential to everyday life. See Elkin Rubiano, “Rios y silencios by Juan Manuel Echavarría,” H-ART. Magazine of History, Theory and Art Criticism, no. 3 (2018): 315–23, https://www.academia.edu/37136012/R%C3%ADosy