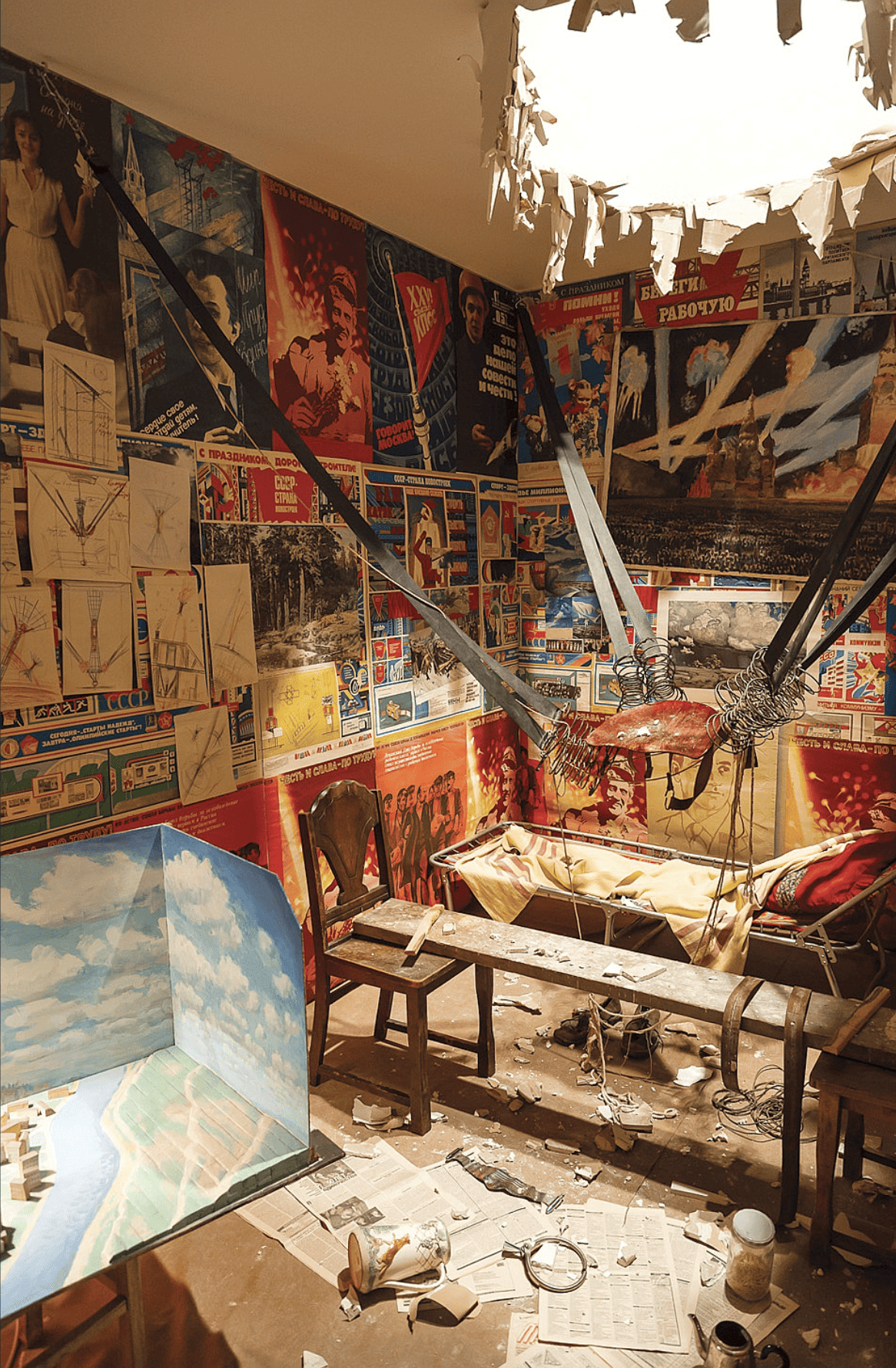

Like the subject of his world-renowned installation The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment (1981–88), artist Ilya Kabakov is no longer with us. While this reality was inevitable, pronouncing it still remains difficult. The giant hole in the ceiling of this installation—left by its protagonist, who abandoned his isolated Soviet existence by catapulting into the cosmos—mirrors that left by Kabakov in the art world, in society, and in our hearts in the wake of his death.

Born in 1933 in what is today Dnipro, Ukraine, Kabakov spent his formative years in the Soviet Union, immigrating via Western Europe to the United States in the late 1980s, when he was well into his fifties. He claimed, “I consider myself a Soviet artist. . . . I am a Soviet person. . . . My texts are Soviet texts”1Renee Baigell and Matthew Baigell, Soviet Dissident Artists: Interviews after Perestroika (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 147. In an interview with David A. Ross, Kabakov repeated, “My mentality is Soviet. . . . I did feel I was Soviet.” Kabakov and Ross, “Interview with Ilya Kabakov,” in Ilya Kabakov, ed. David Ross et al. (London: Phaidon, 1998), 8. In contrast, Emilia prefers the identification “American artists born in the Soviet Union.” Emilia Kabakov, email to author, December 25, 2017. In a 2015 conversation with the author, when asked how the couple identifies, Emilia claimed, “We have a very ambivalent position, in respect to ourselves as well as the international art world.”

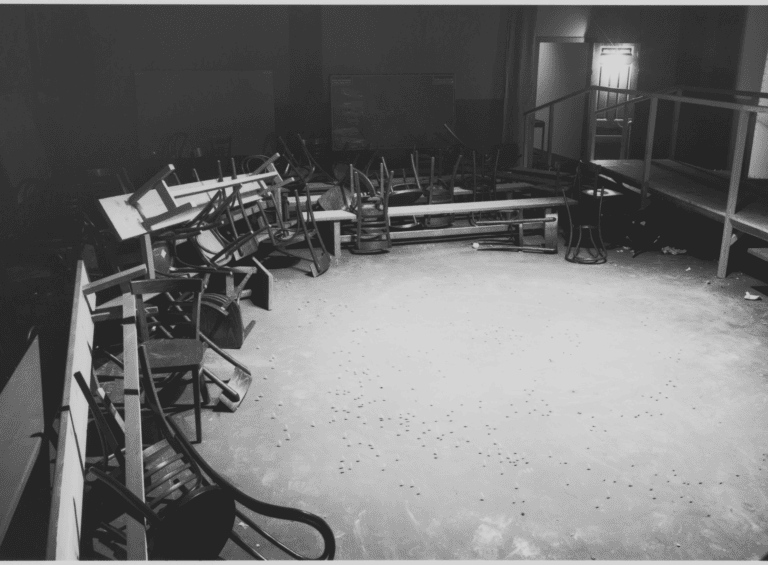

Much of the artist’s work, which he produced over the course of his more than seventy-year career, mirrors his own life. In addition to The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, his characters, namely those from his Albums or portfolios of sequential art, including Flying Komarov (1970–74), Looking-out-the-Window Arkhipov (1970–74), and Sitting-in-the-Closet Primakov (1970–74), are all dedicated to distinct but fictional subjects experiencing existential crises in the face of the Soviet regime. Kabakov devised them on paper throughout the 1970s and early 1980s and eventually mounted some of them as installations—as was his original intention—in the 1988 exhibition Ten Characters at Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York. What followed were numerous international engagements, including his participation in Robert Storr’s group exhibition Dislocations at The Museum of Modern Art in 1991–92 and his commission for documenta IX in 1992. Storr, then a curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture, brought Kabakov into conversation with six large-scale installation artists from the proverbial “West”—Louise Bourgeois (American, born France, 1911–2010), Chris Burden (American, 1946–2015), Sophie Calle (French, born 1953), David Hammons (American, born 1943), Bruce Nauman (American, born 1941), and Adrian Piper (American, born 1948)—in a show exploring the impacts of space and place on our thinking.

Thus, as the Soviet Union was crumbling in the late 1980s, Kabakov was being propelled into fame. In the book Exhibit Russia: The New International Decade, 1986–1990, curator Kate Fowle easily gets caught up in the numbers: between 1988 and 1999, Kabakov participated in an average of thirteen shows per year—twenty-three in 1993 alone—on five out of the seven continents.2Kate Fowle, “The New International Decade, 1986–1996,” in Exhibit Russia: The New International Decade, 1986–1996, ed. Ruth Addison and Kate Fowle (Moscow: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2016), 17. Emilia Kabakov cites that by 2008, they had made more than four hundred installations and participated in more than six hundred exhibitions. Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Enter Here, directed by Amei Wallach (New York: First Run Features, 2013), DVD. Nine years later, in 2008, the artist’s Beetle (1985) became the most expensive painting by a living “Russian” artist when it realized £2.9 million at auction.3The use of “Russian” in this context is a misnomer, per the discussion of Kabakov’s identity herein. Phillips, Important Contemporary Russian Art—Property from a Foundation, sale cat., London, February 28, 2008, lot 14, Ilya Kabakov, Beetle,” https://www.phillips.com/detail/ILYA-KABAKOV/UK010008/14. In 2013, Roman Abramovich and Dasha Zhukova, founders of Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, spent an estimated $60 million on one of the largest private collections of Kabakov’s early works, including his series Holiday (1987).4This was the collection of John L. Stewart. Katya Kazkina, “Billionaire Abramovich Buys Historic Kabakov Collection,” Bloomberg.com, January 28, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-01-29/billionaire-abramovich-buys-major-collection-by-russian-kabakov. This group of twelve paintings, which he made immediately before his immigration, features saccharine Socialist Realist scenes overlaid with crinkled candy wrappers that have been tacked onto the surface of the canvases.

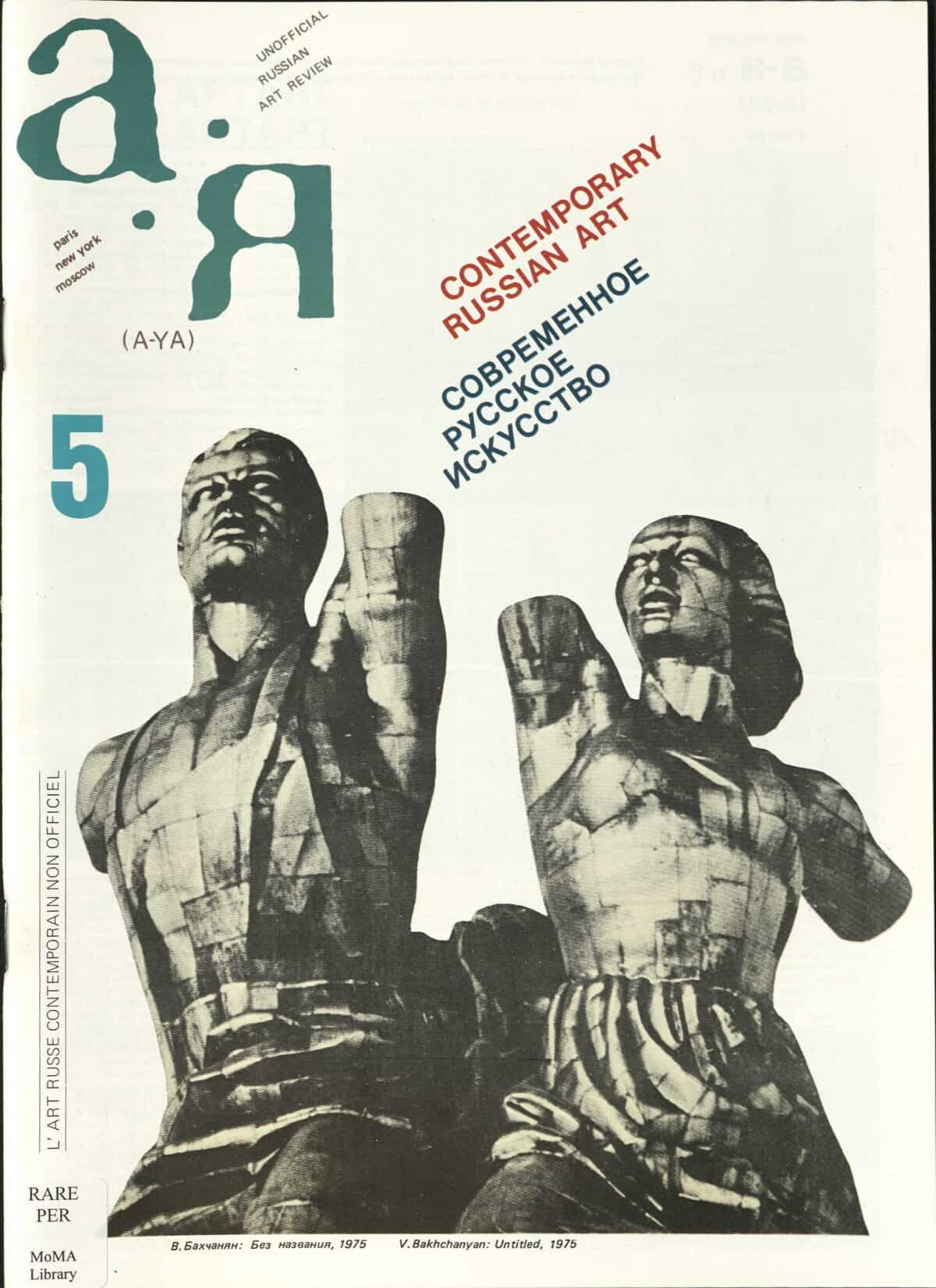

Whether it was his innate nature or his humble Soviet roots, Kabakov was always ready to admit fallibility. “Not everyone will be taken into the future,” he declared in a text first published in 1983 in A-Ya, an art magazine written and produced by Soviet émigrés in Paris and New York.5Ilya Kabakov, “Not Everyone Will Be Taken into the Future” / “V budyshchee vos’mut ne vsekh,” trans. K. G. Hammond, A-Ya 5 (1983): 34–35. For a complete history of the magazine, see Elizaveta Butakova, “A-Ya Magazine: Soviet Unofficial Art Between Moscow, Paris and New York, 1976–1986” (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2015).

In this short allegorical text, he explains that based on the fortitude of their character, people fall into one of three groups: those who take, those who are taken, and those who are left behind. Whether among the living or the dead, the haves are always separated from the have-nots. Those who make the cut end up in the future by way of history books while the remainder fall by the wayside, omitted even from the footnotes of history.

Kabakov’s vision and, subsequently, his works of art have secured him a place well beyond the footnotes. Shortly after his immigration, he began working with Emilia Kanevsky (American, born Dnipro, Ukraine, 1945), a distant cousin who had established herself as a curator, art advisor, and overall savvy businesswoman. Their marriage in 1992 formalized their artistic collaboration, which included countless global public projects, museum commissions, print editions, and charitable works produced up until his death.

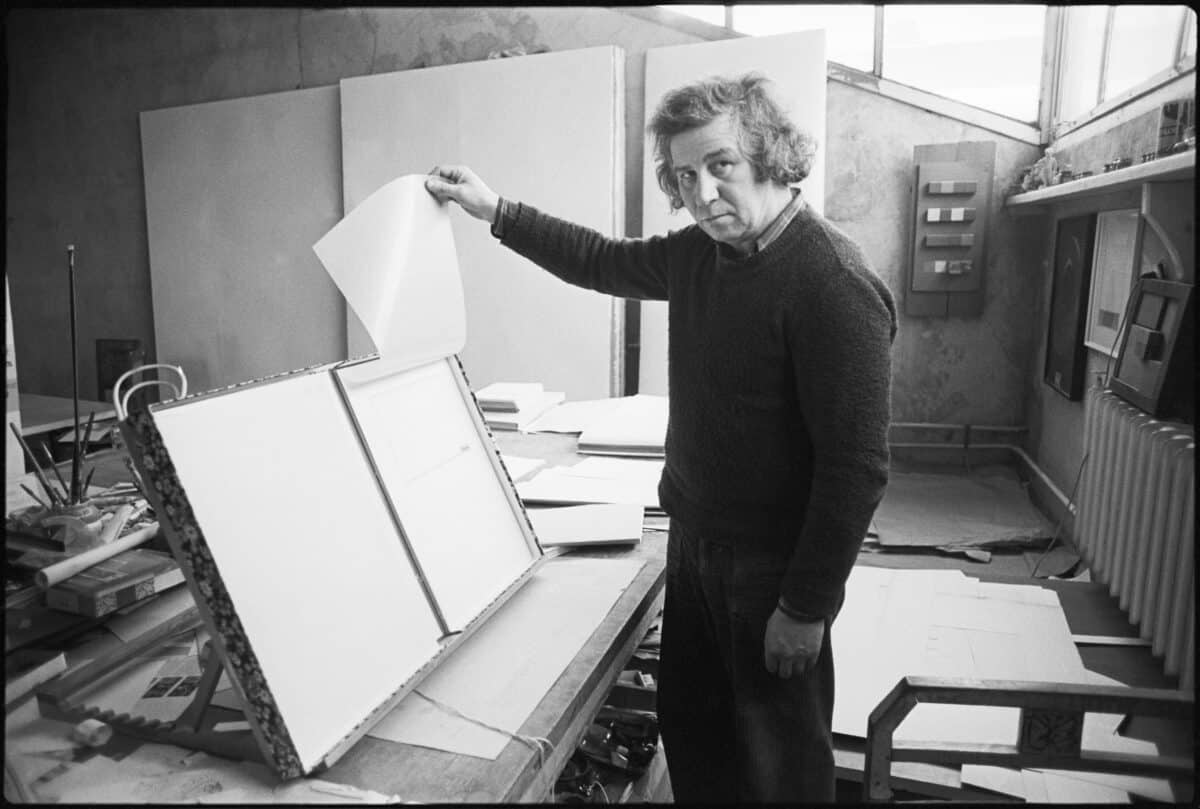

While today many works by Ilya Kabakov can be seen in the collections of museums worldwide, including a number of works on paper at MoMA, the best place to view them remains—as it was during Soviet times—in the artist’s home-studio, which has been on Long Island for almost thirty years. When I was the C-MAP Central and Eastern European Fellow, I organized a visit in July 2016 for group members.

It was sweltering outside, but inside the studio, it was cool and calm. Everything was methodically organized and tidy—from palette knives to boxes of ephemera. We spent hours touring the compound in awe of its mini-museum of maquettes and its viewing room, which is akin to a cathedral. It was clear that, much like in his works, Kabakov created alternative worlds in his life. Grateful to have been immersed in them, we will cherish these memories well into the future.

- 1Renee Baigell and Matthew Baigell, Soviet Dissident Artists: Interviews after Perestroika (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1995), 147. In an interview with David A. Ross, Kabakov repeated, “My mentality is Soviet. . . . I did feel I was Soviet.” Kabakov and Ross, “Interview with Ilya Kabakov,” in Ilya Kabakov, ed. David Ross et al. (London: Phaidon, 1998), 8. In contrast, Emilia prefers the identification “American artists born in the Soviet Union.” Emilia Kabakov, email to author, December 25, 2017. In a 2015 conversation with the author, when asked how the couple identifies, Emilia claimed, “We have a very ambivalent position, in respect to ourselves as well as the international art world.”

- 2Kate Fowle, “The New International Decade, 1986–1996,” in Exhibit Russia: The New International Decade, 1986–1996, ed. Ruth Addison and Kate Fowle (Moscow: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2016), 17. Emilia Kabakov cites that by 2008, they had made more than four hundred installations and participated in more than six hundred exhibitions. Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: Enter Here, directed by Amei Wallach (New York: First Run Features, 2013), DVD.

- 3The use of “Russian” in this context is a misnomer, per the discussion of Kabakov’s identity herein. Phillips, Important Contemporary Russian Art—Property from a Foundation, sale cat., London, February 28, 2008, lot 14, Ilya Kabakov, Beetle,” https://www.phillips.com/detail/ILYA-KABAKOV/UK010008/14.

- 4This was the collection of John L. Stewart. Katya Kazkina, “Billionaire Abramovich Buys Historic Kabakov Collection,” Bloomberg.com, January 28, 2013, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-01-29/billionaire-abramovich-buys-major-collection-by-russian-kabakov.

- 5Ilya Kabakov, “Not Everyone Will Be Taken into the Future” / “V budyshchee vos’mut ne vsekh,” trans. K. G. Hammond, A-Ya 5 (1983): 34–35. For a complete history of the magazine, see Elizaveta Butakova, “A-Ya Magazine: Soviet Unofficial Art Between Moscow, Paris and New York, 1976–1986” (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2015).