Jane Farver, curator and former Director of Exhibitions at the Queens Museum, was invited to MoMA to speak about the exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s, which she co-organized in 1999 with Rachel Weiss (who also came to present on the subject), Luis Camnitzer, and an international team of curators: Okwei Enwezor, Reiko Tomii & Chiba Shigeo, Claude Gintz, László Beke, Mari Carmen Ramírez, Peter Wollen, Terry Smith, Margarita Tupitsyn, Wan-Kyung Sung, Gao Minglu and Apinan Poshyananda. Farver and Weiss (whose talk can be accessed here) were invited to reflect on the exhibition—its challenges, failures and successes—fifteen years after it was seen at the Queens Museum in New York.

This text was part of the theme “Global Conceptualism Reconsidered” developed in 2015. The original content items are listed here.

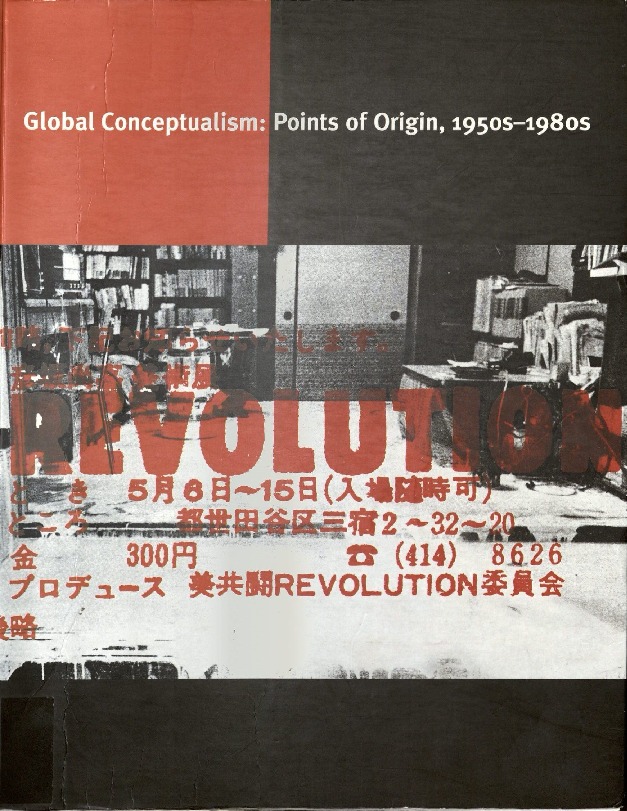

Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950s-1980s was an exhibition that originated at the Queens Museum of Art, New York in 1999, when I was the Director of Exhibitions there. It was on view there from April 28–August 29 and then traveled to the Walker Art Center (December 19, 1999–March 5, 2000), the Miami Art Museum (June 23–August 27, 2000), and the List Visual Arts Center at MIT (October 24–December 31, 2000). As project leaders for the exhibition, Luis Camnitzer, Rachel Weiss, and I worked with a team of 12 international curators representing 11 geographic areas.

Global Conceptualism happened 14 years ago, but it continues to elicit strong opinions. However, I hope we are not here to retry this exhibition but to think about how curators and museums might go about creating exhibitions on a so-called global scale today. For this reason, perhaps some background information about the show might be helpful.

As I remember it, the project began sometime in 1994, when Rachel Weiss and Luis Camnitzer invited me to lunch to ask about the possibility of the Queens Museum organizing an exhibition of Latin American conceptualist art. As discussions ensued, it became clear that each of us knew of conceptualist practices that had emerged and flourished in other parts of the world and that were generally unknown or unacknowledged by the New York art world. These movements of course were connected by a complex system of global linkages, but the important fact was that they clearly had been spurred by urgent local conditions and histories.

Although an exhibition of Latin American conceptualism was badly needed in New York, we decided instead to organize a broader show that would include conceptualist art from around the world, including North America and Europe. From the beginning we understood the territory of “globalism” as having multiple centers in which local events were crucial determinants.

Each of us had our own reasons for wanting to do such an exhibition. When I recently asked Luis to tell me his reasons, he wrote to me that he wanted “to decenter art history into local histories and put the center in its right place as one more provincial province” so that other areas, and particularly Latin America, could, as he says, “do local analysis to help assume local identities that were unmolested by the hegemonic watchtower.” Rachel had a strong desire to demonstrate conceptualism’s political capabilities.

Luis wanted “to decenter art history into local histories and put the center in its right place as one more provincial province”

I had been frustrated by the repeated presumptions by New York art critics and curators that conceptually based, or experimental, if you will, works by international contemporary artists were simply derivative of Western art. There seemed to be a lack of interest or a disregard for the fact that these artists could well have inherited and were responding to their own important local histories.

While New York in the 1990s had seen an influx of contemporary artists from around the world, many of whom were engaged with conceptualist practices, exhibitions of modernism or earlier conceptualism from other parts of the world were still uncommon. Alexandra Monroe’s remarkable 1994 exhibition Scream Against the Sky: Japanese Art after 1945 had sketched out Japanese modern and contemporary art history for audiences in Yokohama, New York, and San Francisco, and there had been a number of exhibitions about Soviet art, including Between Spring and Summer: Soviet Conceptual Art in the Era of Late Communism at Boston’s ICA and The Green Show at Exit Art in 1990, and, in 1991, Perspectives of Conceptualism at the Clock Tower. However, New York had yet to see a museum survey exhibition of conceptualist art from Latin America, Eastern Europe, and many other parts of the world. Information about such work was difficult to obtain, particularly in English, and this void made it easy for New York critics and curators to assume that little that was innovative in conceptualist art was being produced outside of the so-called center.

Until then, the most international museum exhibition of Conceptual art ever staged in New York had been Kynaston McShine’s Information, held at MoMA in 1970. The show included works by more than 150 artists from 15 countries, including Argentina, Brazil, and Yugoslavia. I hoped to expand the dialogue around conceptualism, including North American and Western European conceptualism, and to build on what had been presented elsewhere in several earlier exhibitions.

When we began to work on Global Conceptualism, the movement already possessed an almost 30-year history. One large survey exhibition of Conceptual art: L’art conceptuel, une perspective had taken place at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris in 1989; and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles would mount Reconsidering the Object 1965-1975 in 1996. However, neither of these shows included many works by non-Western artists. There was a third important exhibition, Paul Schimmel’s Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 1998. I will return to this exhibition later.

Rachel, Luis, and I well understood that organizing an exhibition about how conceptualism had developed world-wide would be fraught with problems, not the least of which were the prevailing views. In addition, the physical size and awkward shapes of the Queens Museum’s galleries, the likelihood and eventual reality of a tight budget—although it was larger than those for most Queens Museum exhibitions—and the museum’s small staff were other problems.1On the plus side were some unsung heroes who played a very large role in this project: the Queens Museum’s intrepid director, Carma Fauntleroy, and the staff of the curatorial department, particularly Hitomi Iwasaki, now Director of Exhibitions at the QMA, and Christina Yang, now Director of Education and Public Programs at the Guggenheim Museum.

The thought of how to begin to organize all of the material we potentially wanted to include was a daunting one. One strong influence that soon emerged was the work of historian Eric Hobsbawm. His book about the 20th century, Age of Extremes, offered us a way to think about and sort out how conceptualism had developed in different areas according to what Luis called “local clocks.” The last two chapters of Age of Extremes describes two periods of what Hobsbawm called the “Short Century.” He stated that the “Golden Age” of 1947 to 1973 was a period of both political standoff in the Cold War and unprecedented economic growth; whereas he called the years 1973 to 1991 the “Landslide” period, a time when “the world had lost its bearings and slid into instability and crisis.”2Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1999 (New York: Vintage Books, 1996). These time periods and events seemed to correspond to when and why artists turned to conceptualist strategies in various places, and we decided to use these demarcations as a loose framework for the exhibition.

One strong influence that soon emerged was the work of historian Eric Hobsbawm. His book about the 20th century, Age of Extremes, offered us a way to think about and sort out how conceptualism had developed in different areas.

As we began to think about doing such a show, another reason became increasingly compelling for me. The events that Hobsbawm outlined in his “Golden Age” and “Landslide” periods were echoed in the history of the Queens Museum’s building, which had served as a pavilion in two world’s fairs and from 1946 to 1950 had been the home of the General Assembly of the United Nations, where the independence of a number of emerging nations had been recognized.

The Queens Museum and other New York City borough museums were created in the early 1970s, when activists advocated for the creation of cultural institutions outside Manhattan. This happened while staggering changes were taking place in many parts of the world. The rise of urbanization, the abandonment of an agricultural way of life, and the proliferation of repressive governments, and radical changes in US immigration laws, attracted millions, to the US and to the Borough of Queens. The histories that were outlined in Global Conceptualism were not abstract to our Queens constituents; they were their histories, and it seemed important to present at least a portion of these histories through art, to the best of our ability.

Because we did not want one grand narrative for the show, we wanted to invite a team of international curators to work with us. Since information about artistic production in many parts of the world was hard to access—the Internet and JStor were in their infancies, and Google would not even be incorporated for another three years—we relied on exhibitions we had seen, what we had read, and recommendations from colleagues to put together our team. The geographical demarcations now may seem haphazard, but at the time we were interested in putting forth information about the conceptualist activities of which we were aware, and in inviting curators we knew were working with this subject.

The curatorial team would choose 240 works by more than 130 artists to trace three decades of the history of conceptualist art through two relatively distinct waves of activity. The first, from the late 1950s to about 1973, included works from Japan, which were selected by Reiko Tomii and Chiba Shigeo; from Western Europe, selected by Claude Gintz; from Eastern Europe, selected by Lásló Beke; from Latin America, chosen by Mari Carmen Ramírez; from North America, selected by Peter Wollen; and from Australia and New Zealand, chosen by Terry Smith. The second part examined the emergence of conceptualism from the mid-1970s to the end of the ’80s. Margarita Tupitsyn chose artists from the Soviet Union; Okwui Enwezor made the selections from Africa; Wan Kyung Sung from South Korea, and Gao Minglu from China. Stephen Bann wrote the introduction to the catalogue and Apinan Poshyananda contributed an essay on conceptualist activity in Southeast Asia, much of which fell outside the show’s timeline and was not included in the exhibition.

Most of our invited curators were obvious choices because of their previous work on the subject. Finding a curator for the Eastern European section proved to be the most difficult. The very term “Eastern Europe” was highly contested, and while a number of curators we talked with were familiar with conceptualist activities not only in their own areas but also in the US and Europe, most could not speak about what had taken place in regions neighboring theirs. Fortunately, the Hungarian curator Lásló Beke agreed to take on this task. Probably the most controversial invitation was the one extended to the organizer of the North American section. It was offered to Peter Wollen because of a mutual interest in exploring North American Conceptual art in relation to Situationism and activism. I will always be grateful to this remarkable group of curators, and I continue to be amazed by how prescient their work was for the time.

The budget for the project was, as we had imagined, very modest, but the Andy Warhol Foundation gave its first-ever planning grant to the Queens Museum to get the project started, and the Rockefeller Foundation provided funds for a meeting of the curators, which took place midway through the project at the Bard Center. It is unfortunate that there were no funds for multiple meetings, or that something like Skype did not exist then, as additional contact would have helped to tease out links and networks among artists in various areas. As it was, the meeting at Bard was fairly successful. It has often been my experience that when curators are exposed to new artists and works, they begin to incorporate them into their own practices, and so we went into the meetings with eleven wildly different shows, and emerged with eleven mildly different shows, but we never really expected all of this to gel into one harmonious vision.

…we went into the meetings with eleven wildly different shows, and emerged with eleven mildly different shows

Other funds for the exhibition came from numerous smaller grants: AT&T provided one, as did Shisheido, but contrary to what has been written, there were no huge multinational corporate donations.3James Meyer, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s,” Artforum 38, no. 1 (Sept. 1999).

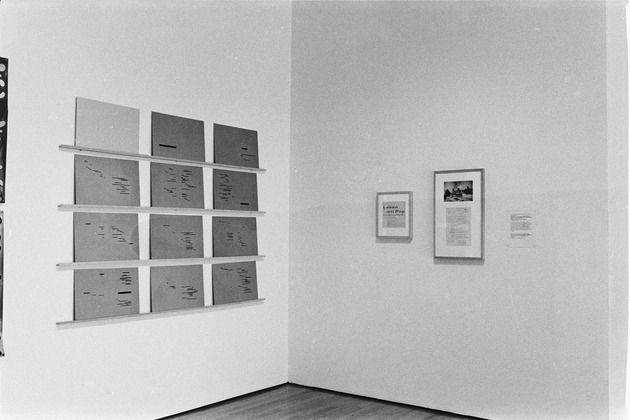

The project was plagued by a customs strike that delayed the arrival of works from Latin America until the very day of the opening. Our book editor left us mid-project. Exhibition designer Michael Langley generously helped us determine where to build walls, but we did not have the budget for a full exhibition design, so each curator decided on the placement of works within the spaces they were allotted. I was taken aback recently when I was contacted by a young art historian intending to write a thesis on the exhibition’s layout and design.

The show opened to mixed reviews, mostly negative if they were by US critics and better if the critics resided elsewhere. James Meyer criticized us in Artforum for “jumping on the global bandwagon” and for “funding the show through the support of multinational corporations,”4James Meyer, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s,” Artforum 38, no. 1 (Sept. 1999): 182. although, as I mentioned earlier, this was hardly the case. I wish he had simply asked about the budget; I probably would have told him, as there was nothing to hide.

Many critics longed for a thematic rather than geographical and chronological organization of the show. Art in America critic Marcia Vetroq thought that concentrating on grouping similar themes and strategies would have animated the show, and she also called the North American section “intellectually dishonest.”5Marcia E. Vetroq, “Conceptualism: An Expanded View,” Art in America, 87, no. 7 (July 1999): pp.71—77. In his New York Times review, critic Ken Johnson also wanted to group similar types of work together, enabling the viewer to more easily compare works from widely separated places.6Ken Johnson, “Conceptual But Verbal, Very Verbal,” The New York Times, May 7, 1999. Joan Kee, writing in Parachute, thought it might have made more sense to group works according to formal similarities and wanted to see Algerian Rachid Koraichi’s work next to text-based works from Europe and Japan, in order to, as she put it, “suss out the issues of using text in art.”7Joan Kee, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950-1980 (exhibition),” Parachute: Contemporary Art Magazine (Jan.1, 2000). However, Ana Tiscornia, writing in Art Nexus, seemed to understand the value of providing histories, “regardless of the degree of thoroughness,” and applauded the show for making works known “beyond the sphere in which they were created.”8Ana Tiscornia, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950’s-1980’s,” Art Nexus (Bogota, Colombia) 34 (Nov.-Jan. 2000): pp. 92-95.

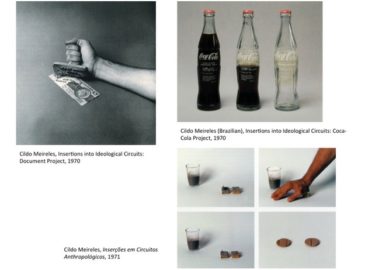

A number of critics quibbled with the geographic delineations, which would not have been so apparent in a thematic hanging. And there were many instances in the exhibition where works could have been grouped thematically. Gerhard Richter and Konrad Lueg’s Life with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism (1963) might have hung next to Oscar Bony’s 1968 work, La familia obrera (Proletarian Family),9Richter and Lueg’s Life with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism (1963)documented the artists’ sitting as commodities in a department store; Bony’s La familia obrera (Proletarian Family) was a living tableau in which the members of a family earned twice their normal wage posing as art in 1968 at Experiencias 68 Institute Torcuto di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina; in Vivo dito works (from 1962) Greco drew circles around people and animals and declared them to be living works of art; and in 1965, Happsoc declared that the inhabitants and buildings of Bratislava were an artwork. and been joined by Alberto Greco’s Vivo dito (1962) and Happsoc’s declaration that the inhabitants and buildings of Bratislava were an artwork (1965). Perhaps Akasegawa Genpei’s elaborate 1963-66 Model 1,000-Yen Note Incident and Cildo Meireles’s 1975 rubber-stamped Brazilian currency Who Killed Herzog? might have been placed near Yves Klein’s Sale of a Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility: Sale to M. Blankfort and Miklos Erdély’s Unguarded Money. These could have been seen as works dealing with money, currency, and value, or artists’ insertions into existing methods of distribution, in which case they could have been joined by works by Eduardo Costa, Antonio Manuel, and Yoko Ono and John Lennon. Tamás Szentjóby and Kendall Geers both employed bricks in their works to very different ends. One could have brought together written paintings by Ono, Leon Ferrari, Willem Boshoff, and Rachid Karaichi. However, it would have been doubly important to provide context for these works, since, for instance, artists working under so many different systems, both socialist and capitalist, may have created works with formal resemblances but with unrelated sources of inspiration, or which considered the public and the private in vastly dissimilar ways. Dematerialization can be inspired by many disparate sources: Buddhism influenced the works of Matsuzawa Yutaka (Independent ’64 Exhibition in the Wilderness, 1964) and Song Dong (Water Diary, 1995, evaporated calligraphy made with brush and water), while North American Conceptual art drew upon the ideas of Duchamp and various Western philosophers.

Originally, I had wanted to organize the show thematically and had asked each curator to choose 10 representative objects, hoping for a show that was manageable in size and budget. However, the curators rebelled, feeling it was important to try to present short histories of each region, however imperfectly. Some felt that taking a thematic approach and comparing a few lesser-known, so-called peripheral artists and works with much better-known examples would again privilege the mainstream and fail to provide necessary context. In the end I agreed, and we organized the show geographically and chronologically.

Even so, Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight complained that American and European Conceptual art had been born in reaction to very specific artistic traditions unique to Western culture, and that bringing together under the umbrella of global conceptualism Xu Bing’s nonsensical Chinese calligraphy (the pseudo-calligraphy he referred to was in fact the work of Gu Wenda, pseudo characters of “still” written by three men and three women, 1986), Antonio Caro’s Colombia Coca-Cola, and Joseph Kosuth’s dictionary definition of Meaning tended to homogenize them.10Christopher Knight, “Reading ‘Global Conceptualism’ Catalog Is almost better than Seeing the Show,” Los Angeles Times, June 23, 1999.

Many critics complained about the disparate texts and labels in each section, which was a consequence of the many voices participating in this conversation. Writing them in one soothing museum voice would probably have made it much easier for the viewer but may have taken away the voice of the individual curators. In hindsight, I think it would have been better to have more comprehensive and uniform labels. This is one of my regrets about the show.

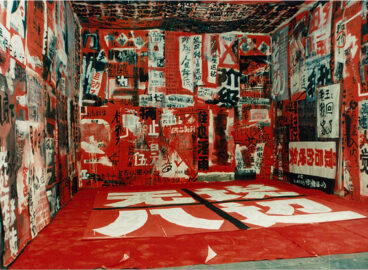

A problem that was pointed out by a number of critics is one that is inherent in presenting historical Conceptual art. Unavoidably, one makes sacred icons out of art and ephemera that were made for the street. Joan Kee regretted our inability to reproduce the freshness of the immediate gesture through photography, and others thought the show seemed gray, but many of these works had been made under difficult circumstances by artists who had very limited means. We were working with what our curators could find.

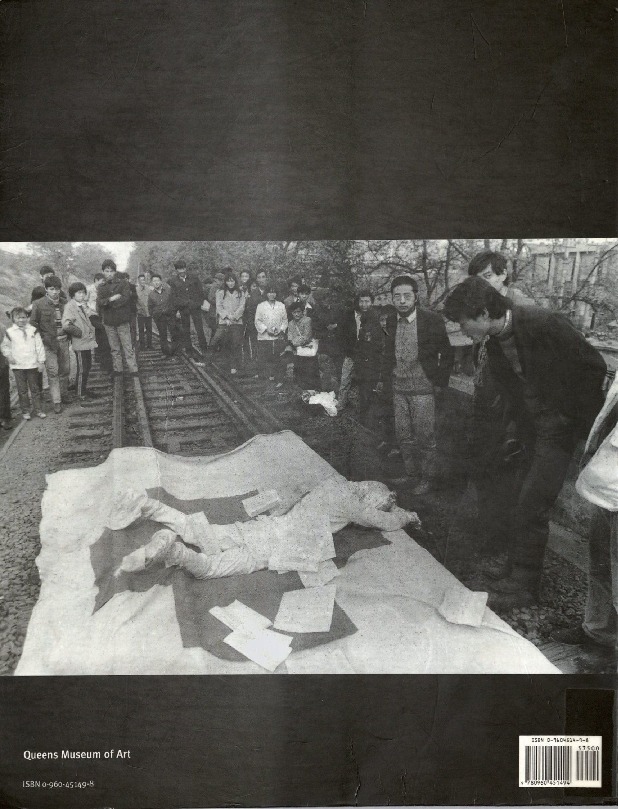

Katherine Hixson, writing in the New Art Examiner, took the show to task for not making more apparent the fact that conceptualism was, in her opinion, but another futile avant-garde utopian effort.11Hixson, Kathryn, “All Together Now! Art and Politics in ‘Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s,'” New Art Examiner, 27, no.3: pp. 32-35. However, I think that claim is contradicted even by our choice of images for the catalogue covers. The front cover featured Japanese artist Hikosaka Naoyoshi’s Floor Event of 1970, an optimistic invitation to the Revolution, while depicted on the back was an image from Wei Guangqing’s Suicide Series, which was shown in the China Avant-Garde exhibition in Beijing in February 1989, an event that many now see as anticipating the tragic events that occurred in Tiananmen Square in June of that year.

In spite of the scathing reviews the show received when it was on view, it soon began to appear on “best show” lists, beginning with the best shows of 1999 and moving on to the best of the previous five and even 10 years. Such citations appeared in Flash Art (Michael Cohen); Bijutsu Techo; Artforum (Dan Cameron); Time Out New York (Tim Griffin); the New York Observer (Marjorie Welish), and others. The exhibition will be included in Jens Hoffman’s soon-to-be-published book Show Time: The 50 Most Influential Exhibitions of Contemporary Art.12Show Time: The 50 Most Influential Exhibitions of Contemporary Art (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2014) Global Conceptualism has taken on a life of its own. Frankly, I am pleased but puzzled by the attention the show itself continues to receive. My fear is that attention that should be focused on the many remarkable artists and works in the exhibition is being directed to the show itself. However, it is exciting to see that this research has begun to happen at MoMA and beyond.

We were asked to address how we would go about creating a show like Global Conceptualism today. If we can assume that there already will have been historical surveys—even abbreviated ones like those in Global Conceptualism—then I would imagine a thematic rather than a geographic hanging. I would still opt out of a grand overall narrative and choose to work with a team to attempt to explicate differences. It would be important to pay keen attention to the artists’ biographies, to where they lived or studied and who they knew, and trace links and networks in a way that we were not able to do in Global Conceptualism.

I said that I would return to Out of Actions, the 1998 exhibition organized by Paul Schimmel for LA MOCA in consultation with an international advisory team that included Guy Brett, Hubert Klocker, Shinichiro Osaki, and Kristine Stiles. It included nearly 150 artists and collaboratives from approximately 20 countries in Eastern and Western Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Japan, and North and South America. I regret that I did not actually see this exhibition, because it, like the others mentioned earlier, did not come to New York, and I had no real travel budget at the Queens Museum. Out of Actions was organized primarily in chronological order, placing artists associated with different movements and countries in proximity to one another and thus allowing connections to be drawn among works that in many cases have not previously been viewed as related. I think this might work, although, as I mentioned above, care must be taken not to iron out the differences too smoothly. Educational programs and information would also be of great importance. It is unfortunate that we did not have the means to conduct video interviews with the artists in Global Conceptualism or to do extensive public programs beyond a symposium that we held in conjunction with the New School.

In her introduction to Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966-1972, Lucy Lippard wrote:

There has been a lot of bickering about what Conceptual Art is/was: who began it; who did what when with it; what its goals, philosophy, and politics were and might have been. I was there, but I don’t trust my memory. I don’t trust anyone else’s either. And I trust even less the authoritarian overviews of those who were not there.13Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966—1972, 2nd ed. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1997), vii.

Although I am of nearly the same generation as Lucy, I was not there either, but these words seem an apt description of the discourse around this exhibition. In the end, I think it was accomplished by sheer good will on the part of hundreds of artists and a team of 15 curators, project directors, catalogue essayists, and one adventurous museum director, all of whom were not only willing but eager to take part in this important conversation.

- 1On the plus side were some unsung heroes who played a very large role in this project: the Queens Museum’s intrepid director, Carma Fauntleroy, and the staff of the curatorial department, particularly Hitomi Iwasaki, now Director of Exhibitions at the QMA, and Christina Yang, now Director of Education and Public Programs at the Guggenheim Museum.

- 2Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914-1999 (New York: Vintage Books, 1996).

- 3James Meyer, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s,” Artforum 38, no. 1 (Sept. 1999).

- 4James Meyer, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s,” Artforum 38, no. 1 (Sept. 1999): 182.

- 5Marcia E. Vetroq, “Conceptualism: An Expanded View,” Art in America, 87, no. 7 (July 1999): pp.71—77.

- 6Ken Johnson, “Conceptual But Verbal, Very Verbal,” The New York Times, May 7, 1999.

- 7Joan Kee, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin 1950-1980 (exhibition),” Parachute: Contemporary Art Magazine (Jan.1, 2000).

- 8Ana Tiscornia, “Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950’s-1980’s,” Art Nexus (Bogota, Colombia) 34 (Nov.-Jan. 2000): pp. 92-95.

- 9Richter and Lueg’s Life with Pop: A Demonstration for Capitalist Realism (1963)documented the artists’ sitting as commodities in a department store; Bony’s La familia obrera (Proletarian Family) was a living tableau in which the members of a family earned twice their normal wage posing as art in 1968 at Experiencias 68 Institute Torcuto di Tella, Buenos Aires, Argentina; in Vivo dito works (from 1962) Greco drew circles around people and animals and declared them to be living works of art; and in 1965, Happsoc declared that the inhabitants and buildings of Bratislava were an artwork.

- 10Christopher Knight, “Reading ‘Global Conceptualism’ Catalog Is almost better than Seeing the Show,” Los Angeles Times, June 23, 1999.

- 11Hixson, Kathryn, “All Together Now! Art and Politics in ‘Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s-1980s,'” New Art Examiner, 27, no.3: pp. 32-35.

- 12Show Time: The 50 Most Influential Exhibitions of Contemporary Art (London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 2014)

- 13Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966—1972, 2nd ed. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1997), vii.