Reflecting on the problematic term “Latin American Conceptualism,” Harper Montgomery’s text stems from a workshop at MoMA in which she and the C-MAP Latin America research group debated some of the issues surrounding the historicization of experimental art in Latin America. The workshop raised a number of questions that are broached below.

This text was part of the theme “Conceiving a Theory for Latin America: Juan Acha’s Criticism.” developed in 2016 by Zanna Gilbert. The original content items are listed here.

We all know that language is enormously important. For art historians, the terms we choose to describe art can significantly affect how it is interpreted and valued. When artworks are deemed “conceptual,” they are inserted into an international field, and comparisons between peripheries and centers become unavoidable. While these comparisons may not always be justified, they are often useful because they help us parse how similar artistic concerns—such as the desire to abandon painting and sculpture and to intervene in social contexts outside art galleries—took different forms in different places. Whether or not we intend to, when we employ the terms “conceptualism,” “dematerialization,” “arte no-objetual,” etc., comparisons are implicitly drawn.

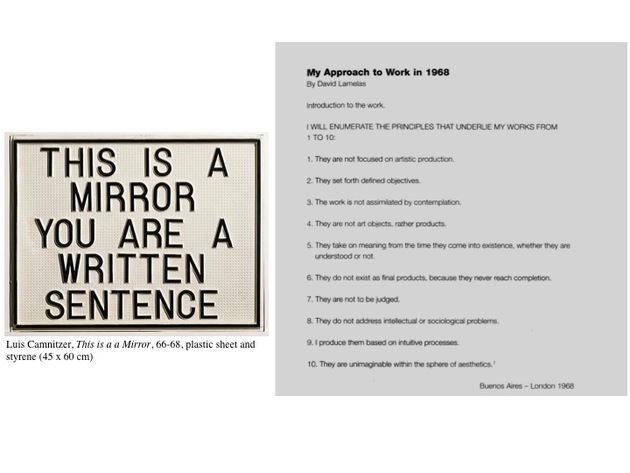

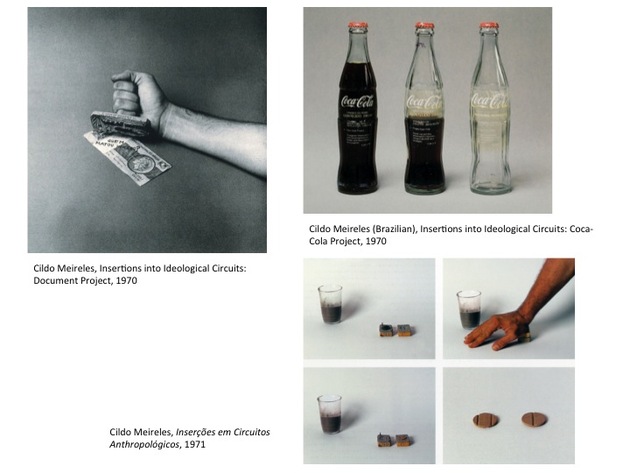

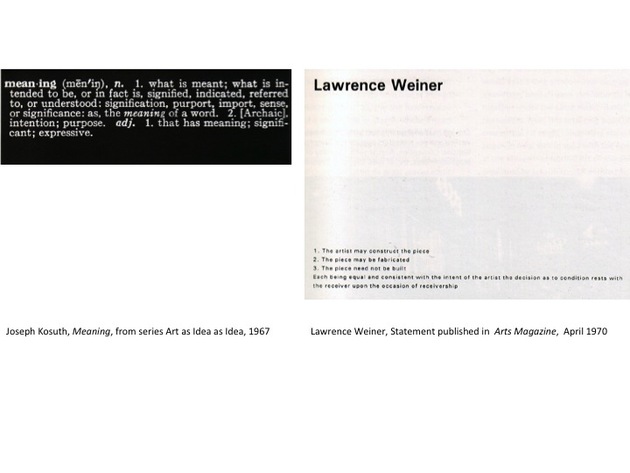

Comparison is the basis of the widely held and often stated view that conceptualism adopted a more political posture in Latin America than it did in the United States. The argument claims that while Latin American artists responded directly to the sociopolitical events of the late 1960s and early 1970s, in New York, artists’ critiques were more circuitous because they were often inscribed within the institutions of the museum and gallery. For instance, the art market was the target of projects by Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, and others at Seth Siegelaub’s gallery in New York during the late 1960s, whereas Cildo Meireles intervened directly in the economic and political systems that control people’s lives during Brazil’s military dictatorship in his series Insertions into Ideological Circuits.1Insertions into Ideological Circuits included the Coca-Cola and Banknote projects (1970). For the former, he printed Coca-Cola bottles with an explanation of the project, with texts such as “Yankees Go Home.” For the latter, he stamped paper currency with messages including “Quem Matou Herzog (Who killed Herzog)?” After being marked by Meireles, objects were returned to circulation. When Mari Carmen Ramírez began using the term “Ideological Conceptualism”2Ramírez cites Simón Marchán Fiz’s use, in 1972, of the term “ideological conceptualism” to describe a tendency he was seeing in Argentina and Spain: “For Marchán Fiz, the distinguishing feature of the Spanish and Argentine forms of Conceptualism was extending the North American critique of the institutions and practices of art to an analysis of political and social issues.” Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds., Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1999), pp. 550–551. in the early 1990s in her landmark essay on Latin American conceptualism, she delineated these differences.3Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds., Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1999), pp. 550–551. And although we need to be able to analyze how Latin American artists can be understood within a global field of conceptualisms, we must also account for how their work developed in contexts entirely separate from centers, which can involve resisting the temptation to compare with what was occurring, for example, in New York. Art historians must enrich the narratives of what Luis Camnitzer calls Latin American conceptualisms’ “local clocks.”4Luis Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007). As scholarship on Latin American art expands and diversifies, we must also ask if conceptualism remains a useful descriptor. Can it account for our growing understanding of artistic experimentation during this exuberant and expansive period? On February 20, 2013, the C-MAP workshop considered the uses and abuses of the term “conceptualism” and its variants.

Conceptualism or Conceptual Art?

“Conceptualism or Conceptual art?” was one of the questions brought up in the workshop. I prefer conceptualism with a small “c,” because it is unimposing yet still claims a place for Latin American artists within the global field of the 1960s and 1970s. Advocates for small-c conceptualism include Luis Camnitzer, who prefers it because it does not wield the authority of a movement as the term “Conceptual art” does. Nor does conceptualism require artists to make art objects.5Camnitzer makes this point with his description of the “aesthetic political” practices of the Uruguayan guerilla group The Tupamaros. Ibid., pp. 44–59. By refusing to quantify art’s development, it also avoids the avant-garde rhetoric of rupture and progress. Conceptual art’s broad historical application has also been questioned by other historians. And a rough consensus has formed that, because it is a historical concept theorized by Joseph Kosuth and the Art & Language group, it is only really relevant to New York and London of the late 1960s.6Alex Alberro, Blake Stimson, and Benjamin Buchloh all draw this distinction. See Alberro, “Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977,” xvi–xxxvii; Stimson, “The Promise of Conceptual Art,” xxxviii–Iii; and Buchloh, “Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,” pp. 514–537, in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology.

Follow-up questions by C-MAP participants asked what should and should not be encompassed within histories of conceptualism in Latin America. They included:

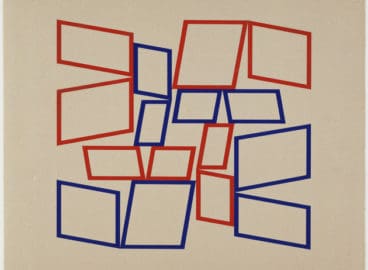

What is the archaeology of conceptual practices in Latin American countries? Can the term “Latin American conceptualism” account for the complexity of genealogies of conceptual and experimental practices that have roots in kineticism, informalism, concrete art and poetry, neo-dada, and auto-destructive practice, to name but a few? The short answer is “probably not.”

“To what extent do neo-dada and neo-surrealist practices between the late 1950s and 1960s belong to a genealogy of conceptual practices? Are we are trying today to recuperate those practices as proto-conceptual when they were not?”

While conceptualism can help define the limits of a period and its concerns, employing it as the starting point for a historiographical process raises doubts about the art historian’s task. Should it be that of tracing origins and genealogies? The term “conceptualism” can reproduce and perpetuate the prejudices of art history. Its failure to account for kineticism, informalism, concrete art and poetry, as well as other key tendencies proves that, instead of encompassing the histories of other experimental practices in Latin America, conceptualism represses them.

Another question from C-MAP participants raised doubts about the capacity of conceptualism as a term to map an adequate art history of experimental practices in Latin America:

What methodologies of research might allow specific histories to emerge while not losing the international, transnational, and networked dimensions of artistic communications from the 1960s to the1980s?

This question cautions us to carefully judge how we use conceptualism to historicize Latin American art. But it also suggests that conceptualism as well as other global rubrics should not be abandoned entirely. What we need are methodologies that can simultaneously analyze episodes from vertical and horizontal vantage points—verticality being the hunt for origins, the archaeological task of setting art history to local clocks; and horizontality the comparative task of identifying transnational points of contact and shared concerns. Alas, the most pressing preoccupation voiced in all of these questions may be summed up with the question: how can we employ methods that locate artists and their work within a time and place that is both specific and transnational? In this scenario, the globalization that imposes terms like “conceptualism” would need to be unpacked and understood as what John Tomlinson has called “complex connectivity.”7John Tomlinson, Globalization and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

Dematerialization

C-MAP workshop participant Luis Enrique Pérez-Oramas questioned the overreliance on the idea of the dematerialization of art. Pérez-Oramas argued that the notion was based on illegitimate claims from the beginning, because dematerialization denies the fundamental materiality of language. “I think we urgently need to deconstruct the idea of dematerialization,” he contended. Language-based art “…doesn’t mean that art is dematerialized. The entire constellation of thinking that built modern and contemporary linguistics stresses the materiality of language as a way to dismantle the humanist ideology of the purity of ideas.” The deployment of language in works by Clemente Padín, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Carl Andre, and Lawrence Weiner supports Pérez-Oramas’s concern.

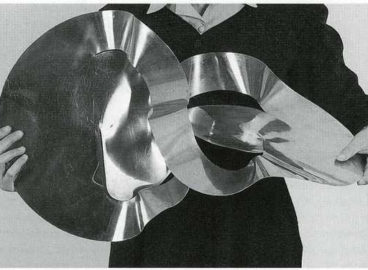

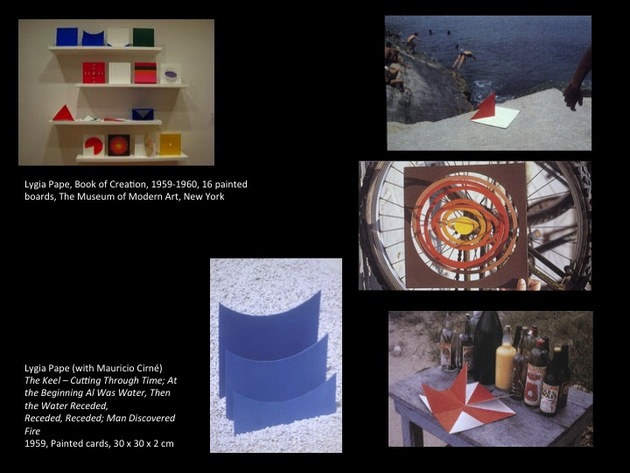

Dematerialization—no doubt linked to the urgency of Lucy R. Lippard’s political stance when she coined it with John Chandler in 1968Lucy R. Lippard and John Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,” in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology, pp. 46–50.—is undergoing a reevaluation. Even the recent retrospective of conceptualism based on Lippard’s book Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object framed its task as “materializing.”9 One reason Brazilian Neo-Concrete artists have been absorbed under the rubric of conceptualism is that they make it impossible to deny the materiality of experimental art during the 1960s and 1970s.

“What are the problematics of interpreting Neo-Concretism as proto-conceptualist because of a desire to assimilate Brazilian artists into a global art history?”

The Brazilians also show that dematerialization has been traded for participation. Seeing participation as a central concern is so useful because through its active engagement of the viewer-participant it reinserts subjectivity into the audience’s experience of conceptual art. Its historical importance, even in New York, can be seen in the pages of the book Kynaston McShine published to accompany his show Information in 1970. McShine emphasized the participatory more than anything else in his essay for the book, describing the “attitude” of the artists as “friendly” and their work as facilitating “experiences which are refreshing” and “therapeutic.”8Kynaston McShine, “Essay,” in Information (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1970), pp. 138–141.

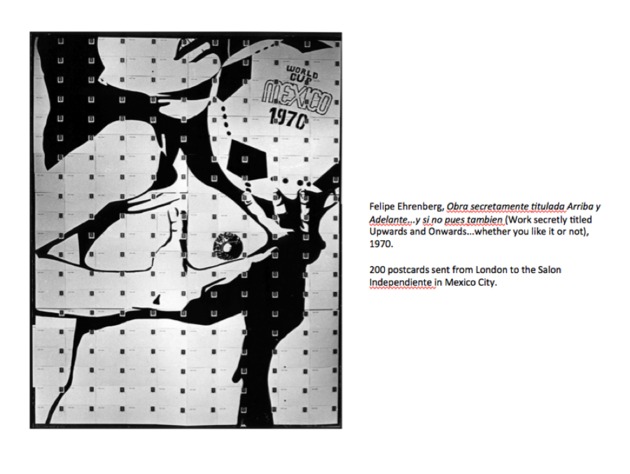

One of the most fascinating proposals of conceptualism—especially conceptualism conceived far from New York—was its incorporation of the methods of global communication into its constitutive fabric. Artists working outside of geographic art centers were necessarily more adept at using systems of distribution than their peers. This sense of the globe as artistic context is expressed by the work of artists associated with the Centro de Arte y Communicación (CAyC) in Buenos Aires, with Clemente Padín and Felipe Ehrenberg’s mail art and magazine projects, among others.9The CAyC, founded in 1968 by Jorge Glusberg, was a center for experimentation in art and new media. Glusberg’s complicity with government abuses under the dictatorship is the subject of important research by Carmen Ferreyra. Looking at the books, journals, and postcards that record these projects—many of which are housed in The Museum of Modern Art’s Library—also reminds us that materiality was central to the meaning of even the most ephemeral of media-based proposals.

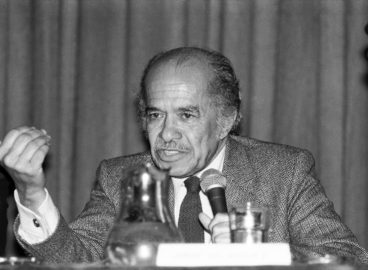

Arte No-objetual

In the end, when they are not digging for archaeological evidence, art historians should be tracking terms back to their historical origins. “Arte no-objetual,” coined by Juan Acha in the 1970s to account for experimental practices then developing in Latin America, is a perfect case in point. The Peruvian-born Acha theorized the concept while he was in Mexico City working with Los Grupos on experimental practices that incorporated performance, media art, and other ephemeral and interventionist tactics. When Acha convened a conference of scholars from Latin American countries in 1981 to debate the question of how to define Arte No-objetual, the answers encompassed new media, performance, and traditional craft and artesania. Arte No-objetual’s antagonism against internationalism and its markets was key. Even now, it is striking that when scholars invoke it to describe experimental practices of the 1960s,’70s, and ’80s, Arte no-objetual still conveys this antagonistic posture.

Miguel López, who has so productively interrogated the terms we use to describe experimental practices in Latin America, has urged us to revisit Acha’s Arte no-objetual. He has also reminded us that subject formation and identity politics are what are ultimately at stake in these debates. Questioning the comparative methods that have forced Latin American conceptualists into the role of authentically political artists, López has argued that these methods have imposed essentialism in merely another form. Looking to compensate for conceptualism’s failure to intervene in life, critics in the United States turn to Latin America. López urges us instead to observe what artists already know: subjects must constantly reinvent and transform themselves in response to fields that change and morph. Thus the art historian should stop trying to nail down the subject and instead begin to study the complexity and dynamism of the field.

- 1Insertions into Ideological Circuits included the Coca-Cola and Banknote projects (1970). For the former, he printed Coca-Cola bottles with an explanation of the project, with texts such as “Yankees Go Home.” For the latter, he stamped paper currency with messages including “Quem Matou Herzog (Who killed Herzog)?” After being marked by Meireles, objects were returned to circulation.

- 2Ramírez cites Simón Marchán Fiz’s use, in 1972, of the term “ideological conceptualism” to describe a tendency he was seeing in Argentina and Spain: “For Marchán Fiz, the distinguishing feature of the Spanish and Argentine forms of Conceptualism was extending the North American critique of the institutions and practices of art to an analysis of political and social issues.” Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds., Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1999), pp. 550–551.

- 3Mari Carmen Ramírez, “Blueprint Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, eds., Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1999), pp. 550–551.

- 4Luis Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

- 5Camnitzer makes this point with his description of the “aesthetic political” practices of the Uruguayan guerilla group The Tupamaros. Ibid., pp. 44–59.

- 6Alex Alberro, Blake Stimson, and Benjamin Buchloh all draw this distinction. See Alberro, “Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977,” xvi–xxxvii; Stimson, “The Promise of Conceptual Art,” xxxviii–Iii; and Buchloh, “Conceptual Art 1962–1969: From the Aesthetic of Administration to the Critique of Institutions,” pp. 514–537, in Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology.

- 7John Tomlinson, Globalization and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- 8Kynaston McShine, “Essay,” in Information (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1970), pp. 138–141.

- 9The CAyC, founded in 1968 by Jorge Glusberg, was a center for experimentation in art and new media. Glusberg’s complicity with government abuses under the dictatorship is the subject of important research by Carmen Ferreyra.