Writer and curator Miguel A. López offers an overview of Juan Acha’s early articles of the 1960s. Acha established himself as a vigorous critical voice in Peru at a time when Conceptualist artistic approaches and political events such as the riots and military coup of 1968 strongly inflected the local art scene.

Read the essay in Spanish here.

This text was part of the theme “Conceiving a Theory for Latin America: Juan Acha’s Criticism.” developed in 2016 by Zanna Gilbert. The original content items are listed here.

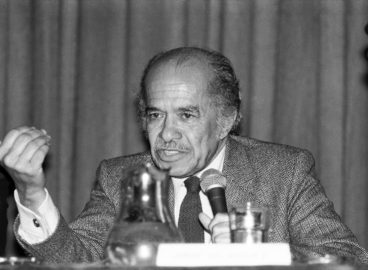

Juan Acha’s critical work is one of the most lucid testimonies of the evolution of aesthetic thought in Latin America between the sixties and the eighties. The shifts and turns in Acha’s discourse during this time are also signs of a series of changes that transformed culture and society in Latin America, which was quickly affected by the international tensions arising from the Cold War and by the emergence of repressive military regimes in many countries in the Southern Cone. Acha was part of a generation of historians and critics including figures such as Aracy Amaral and Mário Pedrosa in Brazil, Damián Bayón and Jorge Romero Brest in Argentina, and Marta Traba in Colombia that engaged in one of the first sustained debates about the state of what came to be known as “Latin American art.” These critics and theorists worked toward generating an interpretive framework through which to think about the arts in their own local contexts, and at the same time tried to formulate alternative responses to the hegemony of artistic discourses from the Northern hemisphere. This led to the creation, in the seventies, of a Latin Americanist discourse that Acha, by urging his contemporaries to produce “independent visual thinking” and to “generate theories of their own,” decisively contributed to.1Juan Acha, “La necesidad latinoamericana de un pensamiento visual independiente,” in Ensayos y Ponencias Latinoamericanistas (Caracas: Galeria de Arte Nacional, 1984), 57–73.

This essay is a preliminary overview of Acha’s early critical work, specifically the articles published in the press from the sixties to the early seventies. Acha was a vigorous critical voice in Peru until 1970, when he decided to leave the country after being unjustly imprisoned and humiliated during the authoritarian nationalist military regime of General Velasco, who seized power in a coup in October 1968. After his release, Acha traveled to the United States, where he stayed for some months before going into exile in Mexico in 1971. The period analyzed here covers the six turbulent years from 1964 to 1970, during which Acha revised his positions regarding abstract and Pop art; encouraged and accompanied the emergence and development of avant-garde aesthetics; and ultimately, in response to the riots of 1968 and the military coup that changed Peru’s social and cultural prospects, redefined his own role as a critic. These were also the years in which Acha started to actively participate in the international art scene through trips and lectures that connected him to the debates taking place in metropolitan hubs around Europe and the United States. Acha was thus an active promoter of new ideas without ever ceasing to insist on the need to rethink and reframe foreign ideas through the filter of one’s own local concerns.

The Early Years

Juan Acha was born in 1916 in the province of Piura in northern Peru. As a young man he traveled to Germany to study at the University of Munich, where he earned a degree in chemical engineering in 1940. On his return to Peru, Acha worked for various branches of Standard Brands Incorporated, and it was not until 1958 that he published his first articles in the newspaper El Comercio under the pseudonym J. Nahuaca—a play on the letters in his real name. Being self-taught did not stop Acha from enthusiastically contributing to the debates about the existence of a supposed Peruvian style of painting that faced the dilemma of identifying its local roots while, at the same time, responding to international aesthetics. In his early writings, Acha questioned the idea of Modernism as a universal paradigm, and inquired into the possibility of local forms of modernity in dialogue with pre-Hispanic aesthetics. At this first stage, Acha took a skeptical, dismissive stance when tidings of Pop art reached Lima around 1962 and 1963 through newspaper articles and columns, although he quickly and drastically changed his views.2One of the first people to introduce the discussion about Pop art into the public sphere was the abstract painter Fernando de Szyszlo on his return to Lima after spending time as visiting professor at Cornell University in the United States. When an interviewer asked, “What did you find most striking about North American painting?,” Szyszlo replied: “People no longer talk much about ‘action painting,’ and young painters and commercial galleries only appear to be interested in a new trend they call Pop-Art. . . . Its symbol may be a huge and disturbingly realistic papier-mâché hamburger by [Claes] Oldenburg, which has been acquired by The Museum of Modern Art in New York. . . . It is neo-Dada without the rebelliousness and the novelty of the original.” Fernando de Szyszlo, “Identidad, problema de la pintura peruana: Szyszlo,” El Comercio, Lima, June 17, 1963, 10. At around the same time, Juan Acha participated in a public debate on Pop art at Art Center Gallery, with the director of the National School of Fine Arts in Peru, Juan Manuel Ugarte Eléspuru, and Szyszlo. At this event, Acha argued vehemently against Pop art. See “¿Será el ‘Pop Art’ una moda transitoria?: un producto del snobismo es ‘el arte de las cosas.’ Así opina Fernando de Szyszlo,” La Prensa, Lima, August 25, 1963, 6.

1964 was a watershed year for the Peruvian avant-garde. Two major shows at the Instituto de Arte Contemporáneo (IAC) in Lima broke the hegemony of expressionist and lyrical abstraction in the local art scene: a striking showcase of Op art by Argentinean painter Rogelio Polesello, and an exhibition of geometric abstract painting by the German artist and co-founder of the Bauhaus school, Josef Albers. Acha responded to both exhibitions with passionate reviews, which quickly became key texts for younger generations. Similarly, Acha’s extensive articles on the 32nd Venice Biennale and Documenta 3 in Kassel, published in El Comercio, made him the best-informed local critic at the time.3See the following texts by Acha: “El ‘Homenaje al Cuadrado’ de Josef Albers,” Cultura Peruana 195–96, Lima, October–December 1964, n.p.; “Rogelio Polesello en el IAC,” El Comercio, Lima, December 6, 1965, sec. 2, p. 7; “La Bienal XXXII—Venecia,” Cultura Peruana 193–94, Lima, July–September 1964, n.p.; “La Documenta III,” ibid.; and “¿Qué es la Documenta III?,” El Comercio, El Dominical supplement, Lima, September 6, 1964, 9. In all of these texts, Acha made no secret of his desire for a renewal of artistic languages, drawing attention to the possibilities that young artists were opening up by experimenting with forms and materials.

The following year, in August 1965, Jorge Romero Brest—then director of the Instituto Di Tella in Buenos Aires and one of the most important figures in Latin American art criticism—visited Peru. During his stay, he gave six lectures in which he expounded on experimental artistic forms, establishing a climate of controversy and praising the incipient shift from painting and sculpture to ambientes (environments) and “situations” that expand the field of experience.4Jorge Romero Brest presented several activities. The main one was of a series of four lessons entitled “Novísimas formas del arte visual contemporáneo” (Newest forms of contemporary visual art), consisting of a first lecture entitled “‘Imágenes’ y ‘Objetos’” (“Images” and “Objects”) at the Museo de Arte de Lima on August 20; a second entitled “Luz y geometría” (Light and geometry) at the same venue on August 23; a third, “Reivindicación del color” (A Defense of colour) at Universidad de San Marcos; and a fourth, given at the Museo de Arte de Lima on August 27, entitled “De los ‘objetos’ a los ‘ambientes’” (From “objects” to “environments”). He also gave a lecture at the National School of Fine Arts, entitled “Arte argentino 1965” (Argentinean art 1965) on August 21. And lastly, he gave a talk entitled “El problema de la integración de las artes” (The problem of the integration of the arts) at the Society of Architects on August 24. In his lectures, Romero Brest showed color slides of the work of European and North American artists (including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, David Hockney, George Segal, Arman, and Claes Oldenburg), but also of Latin American and Argentinean artists such as Luis Felipe Noé, Rómulo Macció, Eduardo Mac Entyre, Julio Le Parc, and the more radical “creators of objects”: Rubén Santantonín, Marta Minujín, Delia Puzzovio, Juan Stoppani, Delia Cancela, and Pablo Mesejean, among others. See Jorge Romero Brest, “Imágenes y objetos,” ms., August 1965, 23 pp. Jorge Romero Brest Archive, Julio E. Payró Art Theory and History Institute at the Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Box 3-Envelope1-Folio L. For a personal account of his public presentations in Lima, see Jorge Romero Brest, “Vine a Lima para decir,” El Comercio, Lima, August 26, 1965, 2. Acha’s affinity with the winds of change that Romero Brest enticingly brought in through new concepts and images could clearly be seen in an article in which he backed the Argentinean critic’s ideas, and in his increasingly emphatic demands for new risks in the art of young artists.5Juan Acha, “Romero Brest: eco de su tesis,” El Comercio, _El Dominical _supplement, Lima, September 19, 1965, 6. See also Luis Miró Quesada, “Soliloquio con Romero Brest,” ibid., September 5, 1966, 7. The response was not long in coming. A few months before Romero Brest’s visit, a new development heralded new forms of collective organization: the artists’ group Señal (Signal)—which would later become the seed of Arte Nuevo—emerged in March 1965 with a belligerent attitude, exalting the markers of technology and speed, and confronting certain ancestralist abstraction trends. However, the first three ambientaciones (environments), which were presented consecutively on November 3, 4, and 5, were the clearest evidence of the excitement and vehemence of the rising avant-garde. The first was Mimuy, an exhibition of works made by Mario Acha, Miguel Malatesta, and Efraín Montero with recycled waste; the second was a group of “environments,” participatory objects, paintings, and a frustrated happening by Luis Arias Vera; and the third was a bold presentation of assemblages and muñecones (big dolls) made out of plaster, wire, and fabric by Gloria Gómez-Sánchez. All three offered experiences that resisted understanding and provoked uneasy responses, particularly from members of older generations who were incapable of perceiving the profound changes looming beneath the apparently rough and deliberately crude, ephemeral forms.6For a specific analysis of these three “ambientaciones,” see Miguel A. López and Emilio Tarazona, “Erosion and Dissolution of the Object in the Peruvian Art of the 1960s. A First Barely Perceptible Tracking Coordinate,” Papers d’Art, no. 93 (Girona: Fundació Espais d’Art Contemporani, 2007), 189–92. See also the four articles by Juan Acha on these exhibitions: “Próximas exposiciones: Ambientaciones y muñecones,” El Comercio, Lima, November 2, 1965, 3; “La ‘ambientación’ del IAC,” ibid., Lima, November 8, 1965, 18; “Exagerado sentido realista: Exposición de Luis Arias Vera,” ibid., November 9, 1965, 3; and “Actitud legítimamente artística: Gloria Gómez-Sánchez en Solisol,” ibid., November 15, 1965. Going against the flow, Acha published a series of critical reviews but also argued in favor of the need for change in the traditional system of artistic representation.

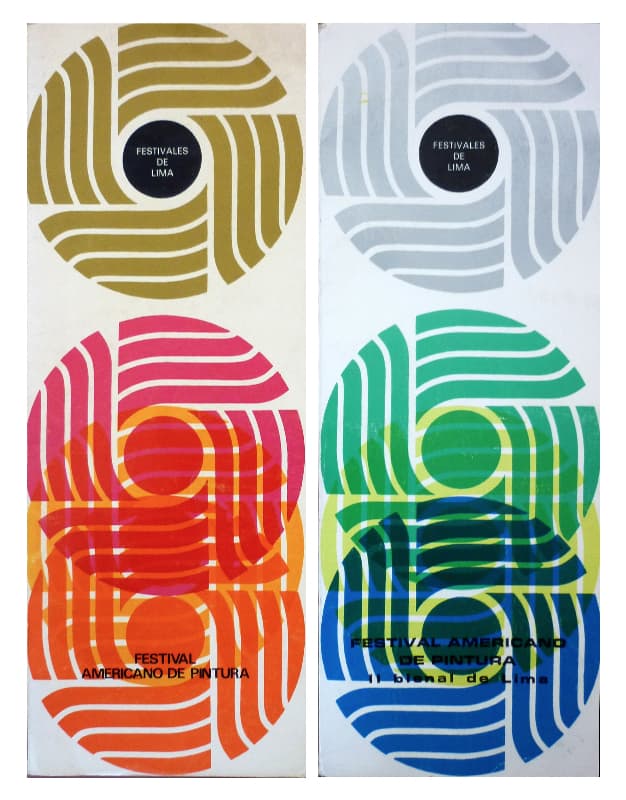

During this same period, new institutions, new sponsors, and new public and private competitions began to boost the presence of Peruvian art on the international scene. One of these milestones was the first Festival Americano de Pintura, also known as the 1st Lima Biennial, organized by the IAC and Asociación Jueves, in October 1966. The biennial was part of the network of American biennials held in several cities in the Latin American continent—starting with Córdoba, Argentina, in 1962—in an attempt to set up a circulatory system for art that would complement the Pan-American “progress and development” program implemented by the United States in partnership with Latin America against the backdrop of the Cold War.7For more on this, see Andrea Giunta, “Bienales americanas de arte. Una alianza entre arte e industria,” in Diana Beatriz Wechsler, ed., Desde la otra vereda. Momentos en el debate por un arte moderno en la Argentina (1880–1960) (Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Jilguero, 1998), [215]–46.

Acha also accompanied the emergence of the group Arte Nuevo (1966–1968), which quickly took a position against the 1st Lima Biennial, accusing it of glaring irregularities in terms of organizational process: a hasty call for entries, a sloppy selection of participants, and the suspicion that the major prize had been adjudicated in advance. Arte Nuevo released a statement urging guest artists to refuse to participate. In a borrowed space in a former shoe store beside Government Palace, the group organized a parallel exhibition, which was enthusiastically reviewed by Acha and by Romero Brest—who had been invited to head the jury of the Biennial.8Once again, Argentinean art critic Jorge Romero Brest was a member of the jury, along with local figures including fellow critic Juan Acha, collector Mario Piacenza, artist Sabino Springett, and Hans van WeerenGriek. See E. M., “Beca de pintura para tres sobres aéreos,” Oiga, Lima, December 2, 1966, 24, 26. Another important event was the series of exhibitions that each Arte Nuevo member presented at Cultura y Libertad gallery in 1967. At the same time, the group held an exhibition at Galería Lirolay (March 27–April 8), which was one of the main promoters of experimentalism in Buenos Aires. So while the Biennial sought to enshrine traditional aesthetics, Arte Nuevo tried to incorporate a new, challenging language, one that would disrupt the traditional criteria for evaluating art.9For a detailed analysis of the events and controversies around the emergence of the group Arte Nuevo in October 1966, see Miguel A. López, “Cosmopolitan F(r)ictions. Aesthetic and Political Redefinitions of a Concept of Avant-garde in the 1960s,” in Arte Contemporáneo. Colección Museo de Arte de Lima, ed. Sharon Lerner (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2013), 16–45.

This explosion of the Peruvian avant-garde in 1965 and 1966 led Acha to write a series of articles criticizing mystifying ideas of art and applauding the way in which some young artists were moving away from the model of the self-absorbed artist and instead embracing technology and the media.10See Juan Acha, “Primer Festival Americano de Pintura,” El Comercio, Lima, November 5, 1966; Juan Acha, “Espíritu renovador: Exposición del Grupo Arte Nuevo,” ibid., November 9, 1966; and Juan Acha, “Las artes visuales,” ibid., January 1, 1967, 8. This shift could also be seen in their use of methods and materials—including stencils and spray and powder paint—which gave their work an industrial look corresponding to the transnational-consumption model to which the middle and upper classes aspired. So from 1966 to 1970, this prolific avant-garde euphorically passed through Op and Kinetic art, through geometric and hard-edge abstraction, and through an upbeat Pop art and flashes of psychedelia, before moving on to ephemeral actions, happenings, environments, and other kinds of work along the lines of Conceptual art. Moreover, the manner in which these artists transitioned through the different languages reflected the diverse ways in which all things new were being assimilated: in a kind of negotiation between the naive glorification of aesthetic cosmopolitism and the symbolic appropriation of dominant languages in order to rearticulate powerful political and critical aesthetic projects based on the pressing needs of the local context.

Reform and Revolution

In early 1968 Acha was still optimistic about the role of the avant-garde in Lima. In the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Nuevas tendencias en la plástica peruana (New Trends in Peruvian Plastic Art), organized to coincide with a visit by delegates from The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Acha wrote a kind of manifesto: “These young artists . . . renounce the idea of art as a work of genius or a charismatic product, and adopt an attitude that is not only rational and volitional but also driven by a desire to grasp reality; in other words, a desire to explore the artistic possibilities of the industrial world that we yearn for and that will—sooner or later—fulfill everyday life for Latin Americans.”11Juan Acha, “La Vanguardia Pictórica en el Perú,” Nuevas tendencias en la plásticas peruana (Lima: Fundación para las Artes, 1968), n.p. The exhibition was held from May 3 to May 20, 1968. At this point, Acha’s arguments were still bound up with an idea of cultural modernity stemming from a transnational-industrial model that was seen as desirable. But this position soon crumbled as a result of the sudden changes in the country’s political and economic directions following the military coup in October, which brought the developmentalist project to an abrupt end.12The developmentalism program was the product of the Cold War as a US defense strategy against socialist and communist ideas and the emergence of national liberation movements throughout Latin America, Asia, and Africa. This economic theory positioned economic development at the center of the political agenda of the so-called third world countries, attempting to implement Northern and Western modernity models of the local industrial bourgeoisie in those countries. Among others, three important elements of developmentalism are “(1) import-substituting industrialization focused on expansion of the capital goods sector, (2) capital accumulation dependent on foreign capital, and (3) broad state intervention in the economy.” Makoto Noguchi, “Introduction: Globalism and Developmentalism,” in Beyond Market-Driven Development. Drawing on the Experience of Asia and Latin America, eds. Costas Lapavitsas and Makoto Noguchi (Oxon: Routledge, 2005), 3.

Soon after this exhibition, Acha embarked on a long journey around Europe. He visited Documenta 4 in Kassel and the 34th Venice Biennale, but he was also directly exposed to the May 1968 riots in France, the echoes of civil rights movements of Black communities, anti-colonial ideas, and the emergence of new political and philosophical positions. His critical discourse was radicalized during this time, and once back in Peru, in 1969, he quickly began to publish articles that spread these progressive ideas and demanded a new place for art within the social and political processes in motion. Acha even gave a series of lectures on “New Sociological References in the Visual Arts” to a small group of local artists and critics with whom he tried to set up a space for discussing the political and social roles of art. These sessions allowed Acha to test the ideas he had absorbed on his travels against the new situation in Peru, which was under the self-proclaimed Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces, led by General Velasco. Acha expounded on the alienating consumption of technology as per theorists from the Frankfurt School (Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse); on the new ideas stemming from French structuralism, psychoanalysis, sociology, and critical re-readings of Marx (Claude Lévi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, Louis Althusser); on mass media, information, and language theories (Marshall McLuhan, Harold Innis, Umberto Eco); and on the aesthetic reception theory developed in the field of literary studies by Hans Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser, since 1967.13All his lectures in this series are included in Temas de arte peruano 3. Nuevas referencias sociológicas de las artes visuales: Mass media, lenguajes, represiones y grupos, Juan Acha, 1969 (Lima: IIMA, Universidad Ricardo Palma, 2008), 19–53.

Like other critics of his generation, including Romero Brest and Marta Traba, Acha sought to create tools for understanding the process of radical transformation of the work of art, as it slowly veered toward increasingly elusive and immaterial processes, actions, and forms of intervention. In his lectures in Lima, Acha compared these new artistic forms with the agitation strategies used by students in the May 1968 riots, which he interpreted as a “cultural act of freedom.” In an open gesture of provocation, he stated: “The streets of some Paris neighborhoods become a medium of information: posters on facades and sentences written on walls and sidewalks proclaim the intentions of the movement and spread a new way of protesting. . . The vocabulary employed in these events quickly spreads throughout the world; or at least to all places in which there are awake, non-conformist young people.”14Ibid.

The increasingly restrictive and repressive atmosphere under the military regime also demanded new kinds of responses from the cultural sector and art world. While a significant number of artists yielded to the reformist processes backed by the regime—including major agrarian reform—others stepped back and criticized the government’s “revolutionary” rhetoric. Acha, who had been an enthusiastic supporter of early Pop art and of the environments and happenings that he had, between 1966 and 1968, interpreted as critical exaltations of reality, now started to question his former position. In this new phase, he called for a renewed, active role for avant-garde art in exposing the ideological underpinnings of the system of art and culture, and argued that cultural production should openly reveal the tensions in its relationship with Peru’s military regime.

This readjustment process led Acha to redefine and test the limits of his role as art critic, at a time when all limits were breaking down. In June 1969 Acha organized a show entitled Papel y más papel: 14 manipulaciones con papel periódico (Paper and More Paper: 14 Manipulations with Newsprint), inviting artists from the avant-garde scene to create a joint “environment” in which he also participated as co-creator.15Presented from June 9 to 21, the project included interventions by Mario Acha, Regina Aprijaskis, Jorge Bernuy, Jaime Dávila, Rubela Dávila, Jesús Ruiz Durand, Queta Gaillour, Gloria Gómez-Sánchez, Emilio Hernández Saavedra, Cristina Portocarrero, José Tang, Gilberto Urday, and Luis Zevallos Hetzel, as well as by Juan Acha himself. For the show, he collected large amounts of old newspapers, which the artists then used to plaster the walls of the room and to build fragile objects, piles, and playful, sensory environments that belied individual authorship. Acha’s participation would have been a way of proclaiming his desire to re-signify his role as cultural operator in Lima by calling into question his privileged role as a legitimator of aesthetic taste in favor of generating spaces for complicity and horizontal creation with his colleagues. Another premise of the show was to renounce the label “artists” and instead use the word “manipuladores” (manipulators) as a direct reference to the craftsmanship involved in working with paper, but also indirectly to the processes of production of social meaning in the public sphere through the mass media. These gestures strengthened the social perspective that Acha brought to the field of aesthetics, highlighting the relations between production of art and the modes of its distribution and consumption at a time when these ideas were not part of local cultural debate.

Utopia and Disillusionment

The process of reform that the military regime embarked on between 1968 and 1970 had raised expectations and garnered the support of some sectors of the left. The expropriation of the International Petroleum Company (IPC) in 1968 and the agrarian reform law in 1969 appeared to meet demands to stop the foreign exploitation of the country’s resources and to defend the interests of disadvantaged social classes. These measures initially brought the government popular support, which nonetheless soon faded as a result of a series of authoritarian gestures, including the expropriation of certain television channels and press outlets and the deportation of intellectuals critical of the regime.

Midway through 1970, Acha had clearly taken a critical stance against the military government, and he wondered how art and culture could turn that reformist process into a truly revolutionary project. In his articles, he reflected on the new confluences of culture and politics at the global level, emphasizing civil protest against the Vietnam War, uprisings against racial segregation, and the beatnik and hippy movements, all of which he considered to be necessary steps toward a cultural revolution with the power to subvert the established values of a society dominated by bourgeois models. Acha was emphatic: “We are witnessing the awakening of a revolutionary spirit; we are headed towards socioeconomic justice, which will supposedly shape a new mind-set. In view of this situation, a group of young artists has started to express—through mimeographed sheets, events, and discussions—the need for a cultural revolution.” He continued: “Cultural revolutionaries or guerrilla do not just want to tear things down. They seek what people fear most: the freedom of individual behavior within the boundaries of human respect.”16Juan Acha, “La Revolución Cultural,” Oiga 386, Lima, August 14, 1970, 31.

Acha never ceased to be a fierce advocate of the experimental spirit, an attitude that made him the target of occasional attacks. For instance, the Colombian-based art critic Marta Traba, who came into contact with the group Arte Nuevo and Acha’s ideas on one of her trips through the countries of the south (Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, and Peru) in 1968, ironically described Acha as somebody “enlightened by MacLuhanism,” whose “passion for technology leads him to harshly stigmatize” the lyrical abstraction of national roots and pictorial idealization of a mythical past that a significant number of Latin American painters were engaged in at the time.17Marta Traba, Dos décadas vulnerables en las artes plásticas latinoamericanas (México D.F.: Siglo XXI, 1973). Traba criticizes the ideas expressed by Acha in his text for the catalogue Nuevas tendencias de la plásticas peruana (1968). Traba argued that the way to set up a “culture of resistance” in Latin America was through a return to abstract painting with ancestral references—as in the work of Fernando de Szyszlo in Peru, José Luis Cuevas in Mexico, and Roberto Matta in Chile, among many others—based on a belief that the avant-garde would be incompatible with underdeveloped contexts. Acha, on the other hand, argued that the avant-garde’s capacity to prevent “the negative effects of the industrialization and the consumer society that we aspire to” made it “essential” for the so-called third world.18Juan Acha, “Risveglio Rivoluzionario,” D’ars 55, Milan, June 1971, 23. I would like to thank Jorge Villacorta for introducing me to this text in 2006. By this time, Acha had already started to incorporate the concept of “revolution” as an objective of artistic praxis, and sought to create the conditions for the radicalization of culture.

New artistic developments in the course of 1970 challenged not only the limits of pictorial language but also its rules and institutional nature, laying the groundwork for ideological and political critiques of the art system (art schools, galleries, art history, museums, the art market, and the notion of cultural prestige) as a whole. In his utopian yearning to imagine possibilities for a cultural revolution, Acha even equated the importance of those attacks against bourgeois culture and traditional art values with the emergence of political insurgency movements: “So, in the event of this true revolution, which is not simply about seizing power or the mere socialist distribution of consumer goods but also a mental revolution, the artist in the advance party would be as essential as the propagator of cutting-edge political ideas, or as important as the armed guerrilla fighter is to supporters of the violent revolution.”19Juan Acha, “Vanguardismo y subdesarrollo,” Mundo Nuevo, Paris, September–October 1970, 75. By 1970 Acha had already begun to call this attitude “cultural guerrilla.”

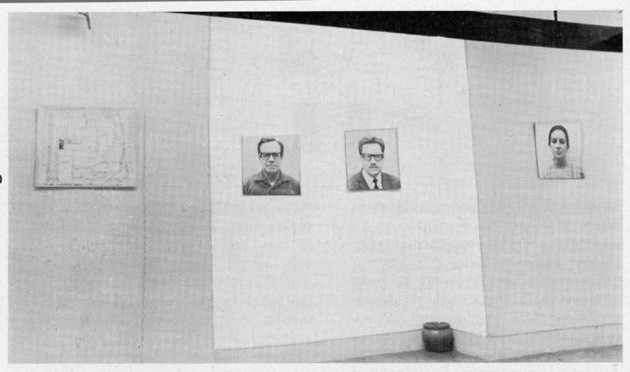

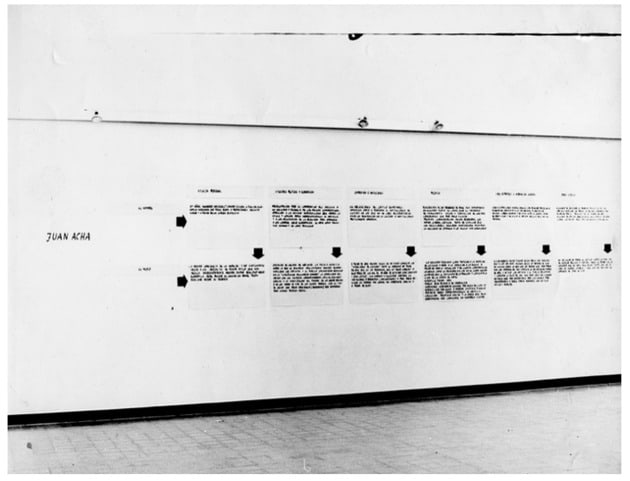

In June 1970 Emilio Hernández (a former member of Arte Nuevo) held an exhibition called Galería de Arte, in which he dismantled the physical and ideological architecture of the gallery Cultura y Libertad through the use of photographs. On the walls of the gallery, he displayed a map of the gallery’s location in the district, its architectural plans, images of an invitation and a newspaper review, and even photographs of the gallery’s staff (the director, the artistic advisor, the secretary, and an employee). Hernández’s exhibition coincided with a show by Rafael Hastings at the Museo de Arte Italiano, which at the time was the temporary headquarters of the IAC in Lima. Hastings produced two works consisting of handwritten texts on large pieces of paper: one set out the development of the history of Peruvian art from 1821 until 1969, and the other charted Acha’s involvement in the art scene (his personal status, his political and economic situation, his institutional commitments, the controversies in which he had been involved during those years, his international travel, and the events he covered as a journalist). The artist critiqued the bourgeois origins of art in Peru and its limited social scope and literally exposed the only art critic at the time who dared to speak out openly against the aesthetic conventionalism of the local scene. Hastings defined this work as an attempt to synthesize “a series of complex critiques around different art-related problems.”20Letter sent by Hastings to the director of the IAC, Alfonso Castrillón, published almost in full in El Comercio. See “Hastings en el IAC,” El Comercio, El Dominical supplement, Lima, June 28, 1970, 39. For a complete photo documentation of this piece, see Miguel A. López, ed., Rafael Hastings. El futuro es nuestro y/o por un pasado mejor. 1983–1967 (Lima: ICPNA, 2014). The show was conceived along similar lines to an action by the artist Ernesto Maguiña, who entered a local art competition with a work consisting of a set of framed photocopies of the terms and conditions, the invitations, the jury statement, and the newspaper reviews of a previous competition.

A later action by Yvonne von Mollendorff further intensified the belligerent mood of the time: in August 1970 the dancer issued an invitation through the press to a dance performance at the IAC. During the show, the artist stood still as a recorded voice describing the apparent movements of a dance performance served as provocation to open what would be a heated debate on the political role of art counter to its mere bourgeois consumption: “All art must be reduced to ashes for it to be reborn pure and real, as it has become a commodity that artists and intellectuals endow with an aura of spirituality, deceiving the masses to the point of cretinization.” The dancer ended the performance by distributing a manifesto that stated, “It is essential to carry out a cultural revolution, for without it there is no social revolution.”21Begoña Ibarra, “Ivonne: El anti-ballet,” La Prensa, 7 Días supplement, no. 634, Lima, August 16, 1970, 20–21. A few months earlier, on February 19, 1970, Yvonne von Mollendorf, together with Jorge Eielson, stormed the Paris metro in an action they called Baller Subterráneo, consisting of a recital of poems by Eielson and drinks served to travelers in the underground carriages. See Emilio Tarazona, Accionismo en el Perú (1965–2000) (Lima: ICPNA, 2006). By then, several of these artists had abandoned the official space of galleries in favor of political agitation and propaganda strategies. Rafael Hastings, for example, performed an action entitled Todo el amor at various parks, where he handed out flyers promoting free love in public spaces. Other examples of cultural activism include an anonymous graffiti series in which the words “Arte = $” were painted on the city’s streets and art gallery facades by a group of students from the National School of Fine Arts with Hastings’s collaboration. However, the most public and passionately discussed renunciation of the art scene was by Gloria Gómez-Sánchez (a former member of Arte Nuevo), in her exhibition at Cultura y Libertad gallery in October 1970. The artist left the gallery empty except for a poster that read: “The space of this exhibition is that of your mind. Make your life the artwork,” which was accompanied by a manifesto stating her decision to switch from aesthetics to ethics.22For a more extensive reflection on the radical experiences of 1970, see Emilio Tarazona and Miguel A. López, “Otra revolución posible. La guerrilla cultural en el Perú de 1970,” in Conceitualismos do Sul / Sur, eds. Cristina Freire and Ana Longoni (Sao Paulo: Annablume, USP-MAC and AECID, 2009), 299–314.

Acha greeted these actions with enthusiasm. He believed that it was necessary to extend the boundaries of art and to modify broader social systems, going as far as to challenge the conservative actions of the military regime: “Even the most radical transformation of socioeconomic structures is not enough to change the basis of human mentality and, as such, of society. Any change must go hand in hand with the cultural and sexual revolution, as young people all over the world have been proclaiming over the past two years.”23Juan Acha, “La revolución cultural,” in ibid. However, these developments were also cut short in an untimely way. The gradual demise of galleries, art centers, and awards as a result of the shrinking of the middle and upper classes, which had sustained the avant-garde, as well as the government’s increasingly repressive measures and the loss of prominent figures who abandoned the art world, lowered the curtain on that period of promising radicalism. The brief imprisonment suffered by Acha in the late 1970s—after he was unjustly and irresponsibly accused of corruption of minors as a result of a police raid on a party where marijuana was supposedly being consumed—was the end of a decade of great expectations. Such humiliation, which did not elicit a action of solidarity from the local art scene, left an indelible mark on Acha’s memory, prompting him to leave Peru and seek exile in Mexico a year later, framing that period within a large halo of profound disenchantment.24Acha’s imprisonment had a profound and irreparable effect on him. Several years later, when asked about his reasons for leaving the country, he recalled with sorrow: “Having been charged [in 1970] and accused of drug trafficking for attending a party of young artists. Then having been stripped of my human condition during ten days in El Sexto [jail] due to the negligence of a judge, before being declared innocent in the corresponding trial. And anybody who has a record of arrest is at the mercy of many types of harassment.” Juan Acha, “¿Por qué no vivo en el Perú?” [reply to a survey of the same name], Hueso Húmero 8, January–February 1981, 108–09.

- 1Juan Acha, “La necesidad latinoamericana de un pensamiento visual independiente,” in Ensayos y Ponencias Latinoamericanistas (Caracas: Galeria de Arte Nacional, 1984), 57–73.

- 2One of the first people to introduce the discussion about Pop art into the public sphere was the abstract painter Fernando de Szyszlo on his return to Lima after spending time as visiting professor at Cornell University in the United States. When an interviewer asked, “What did you find most striking about North American painting?,” Szyszlo replied: “People no longer talk much about ‘action painting,’ and young painters and commercial galleries only appear to be interested in a new trend they call Pop-Art. . . . Its symbol may be a huge and disturbingly realistic papier-mâché hamburger by [Claes] Oldenburg, which has been acquired by The Museum of Modern Art in New York. . . . It is neo-Dada without the rebelliousness and the novelty of the original.” Fernando de Szyszlo, “Identidad, problema de la pintura peruana: Szyszlo,” El Comercio, Lima, June 17, 1963, 10. At around the same time, Juan Acha participated in a public debate on Pop art at Art Center Gallery, with the director of the National School of Fine Arts in Peru, Juan Manuel Ugarte Eléspuru, and Szyszlo. At this event, Acha argued vehemently against Pop art. See “¿Será el ‘Pop Art’ una moda transitoria?: un producto del snobismo es ‘el arte de las cosas.’ Así opina Fernando de Szyszlo,” La Prensa, Lima, August 25, 1963, 6.

- 3See the following texts by Acha: “El ‘Homenaje al Cuadrado’ de Josef Albers,” Cultura Peruana 195–96, Lima, October–December 1964, n.p.; “Rogelio Polesello en el IAC,” El Comercio, Lima, December 6, 1965, sec. 2, p. 7; “La Bienal XXXII—Venecia,” Cultura Peruana 193–94, Lima, July–September 1964, n.p.; “La Documenta III,” ibid.; and “¿Qué es la Documenta III?,” El Comercio, El Dominical supplement, Lima, September 6, 1964, 9.

- 4Jorge Romero Brest presented several activities. The main one was of a series of four lessons entitled “Novísimas formas del arte visual contemporáneo” (Newest forms of contemporary visual art), consisting of a first lecture entitled “‘Imágenes’ y ‘Objetos’” (“Images” and “Objects”) at the Museo de Arte de Lima on August 20; a second entitled “Luz y geometría” (Light and geometry) at the same venue on August 23; a third, “Reivindicación del color” (A Defense of colour) at Universidad de San Marcos; and a fourth, given at the Museo de Arte de Lima on August 27, entitled “De los ‘objetos’ a los ‘ambientes’” (From “objects” to “environments”). He also gave a lecture at the National School of Fine Arts, entitled “Arte argentino 1965” (Argentinean art 1965) on August 21. And lastly, he gave a talk entitled “El problema de la integración de las artes” (The problem of the integration of the arts) at the Society of Architects on August 24. In his lectures, Romero Brest showed color slides of the work of European and North American artists (including Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, David Hockney, George Segal, Arman, and Claes Oldenburg), but also of Latin American and Argentinean artists such as Luis Felipe Noé, Rómulo Macció, Eduardo Mac Entyre, Julio Le Parc, and the more radical “creators of objects”: Rubén Santantonín, Marta Minujín, Delia Puzzovio, Juan Stoppani, Delia Cancela, and Pablo Mesejean, among others. See Jorge Romero Brest, “Imágenes y objetos,” ms., August 1965, 23 pp. Jorge Romero Brest Archive, Julio E. Payró Art Theory and History Institute at the Faculty of Philosophy and Humanities, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Box 3-Envelope1-Folio L. For a personal account of his public presentations in Lima, see Jorge Romero Brest, “Vine a Lima para decir,” El Comercio, Lima, August 26, 1965, 2.

- 5Juan Acha, “Romero Brest: eco de su tesis,” El Comercio, _El Dominical _supplement, Lima, September 19, 1965, 6. See also Luis Miró Quesada, “Soliloquio con Romero Brest,” ibid., September 5, 1966, 7.

- 6For a specific analysis of these three “ambientaciones,” see Miguel A. López and Emilio Tarazona, “Erosion and Dissolution of the Object in the Peruvian Art of the 1960s. A First Barely Perceptible Tracking Coordinate,” Papers d’Art, no. 93 (Girona: Fundació Espais d’Art Contemporani, 2007), 189–92. See also the four articles by Juan Acha on these exhibitions: “Próximas exposiciones: Ambientaciones y muñecones,” El Comercio, Lima, November 2, 1965, 3; “La ‘ambientación’ del IAC,” ibid., Lima, November 8, 1965, 18; “Exagerado sentido realista: Exposición de Luis Arias Vera,” ibid., November 9, 1965, 3; and “Actitud legítimamente artística: Gloria Gómez-Sánchez en Solisol,” ibid., November 15, 1965.

- 7For more on this, see Andrea Giunta, “Bienales americanas de arte. Una alianza entre arte e industria,” in Diana Beatriz Wechsler, ed., Desde la otra vereda. Momentos en el debate por un arte moderno en la Argentina (1880–1960) (Buenos Aires: Ediciones del Jilguero, 1998), [215]–46.

- 8Once again, Argentinean art critic Jorge Romero Brest was a member of the jury, along with local figures including fellow critic Juan Acha, collector Mario Piacenza, artist Sabino Springett, and Hans van WeerenGriek. See E. M., “Beca de pintura para tres sobres aéreos,” Oiga, Lima, December 2, 1966, 24, 26. Another important event was the series of exhibitions that each Arte Nuevo member presented at Cultura y Libertad gallery in 1967. At the same time, the group held an exhibition at Galería Lirolay (March 27–April 8), which was one of the main promoters of experimentalism in Buenos Aires.

- 9For a detailed analysis of the events and controversies around the emergence of the group Arte Nuevo in October 1966, see Miguel A. López, “Cosmopolitan F(r)ictions. Aesthetic and Political Redefinitions of a Concept of Avant-garde in the 1960s,” in Arte Contemporáneo. Colección Museo de Arte de Lima, ed. Sharon Lerner (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2013), 16–45.

- 10See Juan Acha, “Primer Festival Americano de Pintura,” El Comercio, Lima, November 5, 1966; Juan Acha, “Espíritu renovador: Exposición del Grupo Arte Nuevo,” ibid., November 9, 1966; and Juan Acha, “Las artes visuales,” ibid., January 1, 1967, 8.

- 11Juan Acha, “La Vanguardia Pictórica en el Perú,” Nuevas tendencias en la plásticas peruana (Lima: Fundación para las Artes, 1968), n.p. The exhibition was held from May 3 to May 20, 1968.

- 12The developmentalism program was the product of the Cold War as a US defense strategy against socialist and communist ideas and the emergence of national liberation movements throughout Latin America, Asia, and Africa. This economic theory positioned economic development at the center of the political agenda of the so-called third world countries, attempting to implement Northern and Western modernity models of the local industrial bourgeoisie in those countries. Among others, three important elements of developmentalism are “(1) import-substituting industrialization focused on expansion of the capital goods sector, (2) capital accumulation dependent on foreign capital, and (3) broad state intervention in the economy.” Makoto Noguchi, “Introduction: Globalism and Developmentalism,” in Beyond Market-Driven Development. Drawing on the Experience of Asia and Latin America, eds. Costas Lapavitsas and Makoto Noguchi (Oxon: Routledge, 2005), 3.

- 13All his lectures in this series are included in Temas de arte peruano 3. Nuevas referencias sociológicas de las artes visuales: Mass media, lenguajes, represiones y grupos, Juan Acha, 1969 (Lima: IIMA, Universidad Ricardo Palma, 2008), 19–53.

- 14Ibid.

- 15Presented from June 9 to 21, the project included interventions by Mario Acha, Regina Aprijaskis, Jorge Bernuy, Jaime Dávila, Rubela Dávila, Jesús Ruiz Durand, Queta Gaillour, Gloria Gómez-Sánchez, Emilio Hernández Saavedra, Cristina Portocarrero, José Tang, Gilberto Urday, and Luis Zevallos Hetzel, as well as by Juan Acha himself.

- 16Juan Acha, “La Revolución Cultural,” Oiga 386, Lima, August 14, 1970, 31.

- 17Marta Traba, Dos décadas vulnerables en las artes plásticas latinoamericanas (México D.F.: Siglo XXI, 1973). Traba criticizes the ideas expressed by Acha in his text for the catalogue Nuevas tendencias de la plásticas peruana (1968).

- 18Juan Acha, “Risveglio Rivoluzionario,” D’ars 55, Milan, June 1971, 23. I would like to thank Jorge Villacorta for introducing me to this text in 2006.

- 19Juan Acha, “Vanguardismo y subdesarrollo,” Mundo Nuevo, Paris, September–October 1970, 75.

- 20Letter sent by Hastings to the director of the IAC, Alfonso Castrillón, published almost in full in El Comercio. See “Hastings en el IAC,” El Comercio, El Dominical supplement, Lima, June 28, 1970, 39. For a complete photo documentation of this piece, see Miguel A. López, ed., Rafael Hastings. El futuro es nuestro y/o por un pasado mejor. 1983–1967 (Lima: ICPNA, 2014).

- 21Begoña Ibarra, “Ivonne: El anti-ballet,” La Prensa, 7 Días supplement, no. 634, Lima, August 16, 1970, 20–21. A few months earlier, on February 19, 1970, Yvonne von Mollendorf, together with Jorge Eielson, stormed the Paris metro in an action they called Baller Subterráneo, consisting of a recital of poems by Eielson and drinks served to travelers in the underground carriages. See Emilio Tarazona, Accionismo en el Perú (1965–2000) (Lima: ICPNA, 2006).

- 22For a more extensive reflection on the radical experiences of 1970, see Emilio Tarazona and Miguel A. López, “Otra revolución posible. La guerrilla cultural en el Perú de 1970,” in Conceitualismos do Sul / Sur, eds. Cristina Freire and Ana Longoni (Sao Paulo: Annablume, USP-MAC and AECID, 2009), 299–314.

- 23Juan Acha, “La revolución cultural,” in ibid.

- 24Acha’s imprisonment had a profound and irreparable effect on him. Several years later, when asked about his reasons for leaving the country, he recalled with sorrow: “Having been charged [in 1970] and accused of drug trafficking for attending a party of young artists. Then having been stripped of my human condition during ten days in El Sexto [jail] due to the negligence of a judge, before being declared innocent in the corresponding trial. And anybody who has a record of arrest is at the mercy of many types of harassment.” Juan Acha, “¿Por qué no vivo en el Perú?” [reply to a survey of the same name], Hueso Húmero 8, January–February 1981, 108–09.