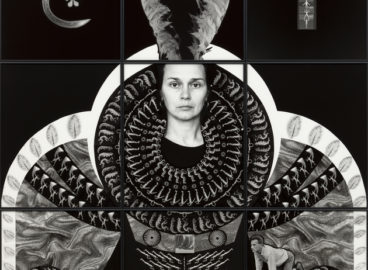

A major new publication, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology, presents key voices of this period that have been reevaluating the significance of the socialist legacy, making it an indispensable read on modern and contemporary art and theory. The publication offers a rich collection of texts and an additional, reexamining perspective to its 2002 sister publication, A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s, part of MoMA Primary Documents publications. For this new book, a series of conversations were commissioned with artists in the region and members of the C-MAP research group for Central and Eastern Europe at MoMA. The following is one of those dialogues, between one of the book’s editors, Ana Janevski, and the artist Sanja Iveković.

Read a review of the publication at Hyperallergic.

Ana Janevski: How do you understand the term and notion of “Eastern Europe” from the perspective of today, almost thirty years after the end of socialism?

Sanja Iveković: To give a definition of Eastern Europe is a difficult or almost impossible task because it’s about a social and cultural construct. I looked at the English-language Wikipedia and found the following sentence: “There are almost as many definitions of Eastern Europe as there are scholars of the region.” What we all know is that at the beginning of the ’90s, the term “Eastern Europe” encompassed all the European communist countries. Although Yugoslavia was not officially part of that bloc, my definition (based on my own experience) includes Yugoslavia as well. After the collapse of the communist regimes, the picture of Eastern Europe completely changed. It became a phantom both for those in the East as well as in the West or, perhaps more apt, a phantom limb. As in the case of that fascinating medical phenomenon when people feel pain in limbs that are not there anymore, today many suffer from nostalgia. [Slavoj] Žižek has the best answer to that: “One should not consider what current time has to say about communism but what the communist idea has to say about current times.”

AJ: You have considered yourself a feminist artist since the ’70s, and the first feminist conference held at Belgrade’s Student Cultural Center in 1978, under the title “Comrade Woman: The Women’s Question – A New Approach?” [“Drug-ca Žena. Žensko Pitanje – Novi Pristup?”], was very important to you. It was the first autonomous second-wave feminist event in Eastern Europe, specifically Southeastern Europe, and it is considered a turning point in Yugoslav history. It paved the way for feminist theory to begin to inform the social and cultural discourse of Yugoslavia, but the new research did not include the visual arts. The feminist reflection of your work came only later. When and how did that happen?

SI: Generationally I am part of the group of Croatian artists that was formed in the ’70s and made a radical break with the local artistic tradition, yet it was still a “male scene.” I encountered feminist art for the first time at the first exhibition of European video art, Trigon ’73 in Graz, which included works by VALIE EXPORT as well as by American artists such as Lynda Benglis, Joan Jonas, Trisha Brown, and Hermine Freed. The following year in Lausanne at the second international exhibition Impact Art – Video Art, I saw works by Eleanor Antin, Martha Rosler, and Yvonne Rainer. And in international art magazine such as Flash Art, Artforum, and Avalanche, I had the opportunity to read about feminist art. I found it all very inspiring, so at my first solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb, in 1976, I showed works that problematized the position of women in society, representations of women in the media, and my own position as a woman artist within the art system. This was two years before the well-known international conference in Belgrade. I started with the practice; the theory came later. I started to educate myself in feminist and gender theory at the “Woman and Society” meetings, which were organized within the Association of Sociologists by a group of feminists who, at the time, were producing a great number of theoretical texts and magazine articles, but who did not recognize visual art as a part of that discourse. Feminist art critique and critical texts from feminist art theory appeared only in the ’90s. The Center for Women’s Studies [Zagreb] had an important role in promoting feminist theory and practice on the local scene. It was founded in 1995, and it is led by feminists, scientists, artists, and women with experience in women’s and civil activism. I was one of the founders, so I taught for several years on the subject of feminist artistic practice. The center has launched a magazine, Third, which also deals with feminist art. The first feminist text about my work was written by Bojana Pejić under the title “Methonimical Moves,” and it appeared in the catalogue for Manifesta 2 published by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb. Yet even today there is no systematic research of the feminist artistic scene, and still some of the women artists don’t want to be called feminist artists, mostly it seems because they think that this “label” would narrow the perception of their work and the meaning of their practice. We should not forget that the myth of art with no gender is still present, and that the [postcommunist] transition brought a remasculinization of society.

AJ: Your socially critical practice has continued until today, and in the last twenty years you have often worked collaboratively with activist groups and civil society initiatives, in Croatia as well as around the world. Why do you find such collaboration important in your practice? And how does the collaborative practice translate into exhibition practice?

SI: I consider the work I do with women’s NGOs an important part of my education. Women’s groups have had a crucial role in the process of building a civil society in Croatia, because they have promoted new organizational models and different ways of articulating their own interests from those in the mainstream or as defined by traditional social rules. I would agree with the argument that women’s groups were fundamental to the process of democratization in the region. Namely, women’s groups were the first autonomous initiatives to organize themselves outside of the existing institutions, like the socialist groups or the unions. My own collaboration with women’s groups was a very precious experience as I started to change the methods and content of my work. The biggest value of the collaborative projects is that the work with other women makes me feel that I am participating in something that is bigger than I am, that has not only a personal but a larger political importance. I was not so familiar with the issue of violence towards women when I started the project Women’s House in 1998; this subject was not so present in the art world. My work has changed since then, everything around us has changed, the borders are fluid, the enemies are more and more invisible, and since I don’t belong to the generation that formed itself in the society of spectacle, I still stubbornly believe that resistance is possible. What concerns me is that today art functions as a place for the discussion of all burning political questions, but this reflection remains within the art system; it doesn’t reach the streets or parliaments.

AJ: You are one of the pioneers of new media, performance, and video art. What are the strategies for effective feminist work today?

SI: I don’t have a prescription for an effective feminist work today. I think that it’s important to abandon the idea that feminism has to deal only with women. In my work, I have always wanted to deal with real problems in society, no matter whether they are about the position of women or the Roma people, marginalized workers and all the other “others.” I always try to critically reflect my own position, my role in the art system as well as what happens to me as a citizen. I think that the strength of the artistic act is not only to reflect social reality but to actively participate in the creation of the collective and social imaginary. It is the role of the artist to find each time a new model to deal with the difficult issues, one which enables the viewer to reflect upon contemporary society and to rethink his or her place in it.