A major new publication, Art and Theory of Post-1989 Central and Eastern Europe: A Critical Anthology, presents key voices of this period that have been reevaluating the significance of the socialist legacy, making it an indispensable read on modern and contemporary art and theory. The publication offers a rich collection of texts and an additional, reexamining perspective to its 2002 sister publication, A Sourcebook for Eastern and Central European Art since the 1950s, part of MoMA Primary Documents publications. For this new book, a series of conversations were commissioned with artists in the region and members of the C-MAP research group for Central and Eastern Europe at MoMA. The following is one of those dialogues, between David Senior and the artist Zofia Kulik.

David Senior: In your studies or in your early practice, were there any models or experiences that shaped your attitude about the possible function of an archive or the importance of the document in the context of changing art practices?

Zofia Kulik: The question about my experience with an archive leads me to my pre- archive practice. Then, I would talk instead about “collecting.” It started when I was around eleven or twelve years old. It was quite popular in the ’50s to collect photos of actresses (not actors) from weekly magazines, and I was very patient and persistent in that. I had a few A3 exercise-books where I pasted pale images (the quality of the prints was not very good). Unfortunately, once they got wet, I had to throw them out. Later, in my sculptural studies, the notion of “preservation” appeared. If you work in clay, a plastic material, then its transformations are natural, and the will or necessity to document changes (a task from the professor) is also natural.

DS: When KwieKulik began organizing an archive for your process-based art practices and also the work of colleagues, was it instigated by a pragmatic need to simply keep order to materials that had accumulated from your practice and your collaborations, or was it more part of the original conceptual framing of the work itself? In other words, was the idea of the archive inseparable, in your conception, from the consideration of the work itself?

ZK: Giving order to materials was never the main aim for us. We used the archive as a “bank” of images, scenarios, quotations, and ideas, and depending on the occasion, we would make a selection—for new arrangements as well as references for new actions. Using old materials in a new way caused new documentation to come into being. That means a new level of complication appeared with many links to past actions. Today, sometimes it is difficult to separate one event from another. It is also difficult to pinpoint which version of public “being” was original. The archive seemed to be for us similar to the clay—plastic structure easily transformed and rearranged. In our theory, we used the term “directed documentation.”

DS: As you developed your own “institution,” the Studio of Activities, Documentation and Propagation [PDDiU], was the founding of an archive in your apartment an effort to fill a void, to correct the neglect of official art institutions in terms of documenting the practices of certain contemporary artists of the time? Was your labor in accumulating materials a response to an understanding that it would not be preserved otherwise in state institutions?

ZK: Exactly, yes. We had a deep conviction that something important would be lost if it was not “captured” by a camera, tape recorder, or at least immediately noted. Poland was a country with little material heritage following various uprisings and wars, especially after World War II. Additionally, after 1945, many names and facts from the past were forbidden to be mentioned in public. So, in our case, documentation was a weapon against permanent “discontinuity” in art history.

DS: As an organization, is it fair to summarize the PDDiU as a method you used to manifest opposition to the existing political and social environment and the institutional bureaucracy of that environment? text

ZK: Yes and no. We did not plan to manifest any opposition. Yet that is what happened. We never wanted to be underground; we wanted the PDDiU to be a public place. As it turned out, our fight for that project produced documentation, which portrayed that moment and our environment very well. The history of PDDiU is now the subject of research and study. But for me it does not cause pleasant memories. You must know that if you fight with bureaucracy, you create your own. When I recollect all those letters, complaints, meetings, expectations, even now I feel exhausted.

DS: During the 1970s, KwieKulik were in a fairly constant dialogue with various state bodies in Poland in regard to potential funding for your activities—though the funding never materialized. Part of your practice involved this kind of attempt to get inside the state apparatus, even after you had been blacklisted by the Party in the late 1970s. In retrospect, could you imagine how the archive would have functioned if somehow it had been included under some state body and supervision?

ZK: I think, and Paweł Kwiek probably would not agree with me, our archive could not be included by any state or institutional body, not only because of the politics of that “body” but also because of our basic concept and practice. What I said before, we treated the archive as a palette for building still new “entities” (compositions, arrangements, presentation sets, and so on). What institution would agree to such creative but unpredictable use of the archival “stock”?

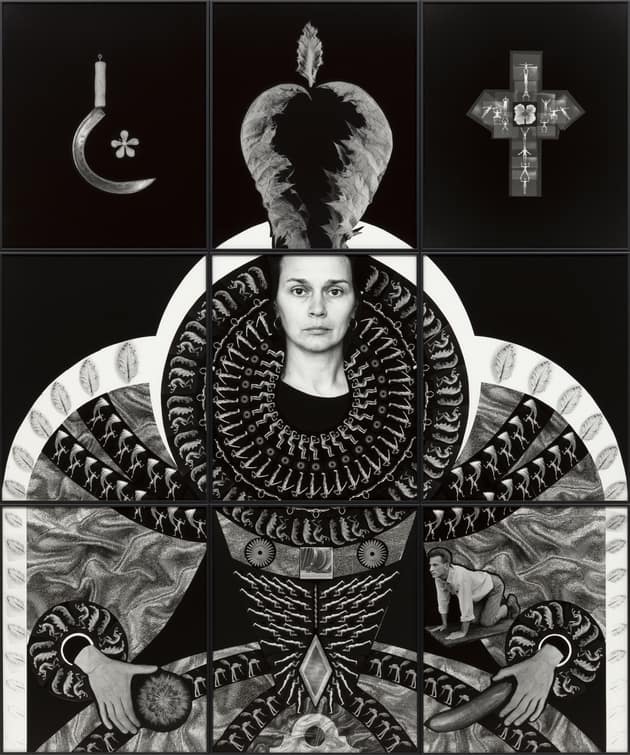

DS: Your practice in the last decades has continued to involve these processes of building and maintaining archives. For example, a work like From Siberia to Cyberia[1999] involved amassing a huge amount of images to create a major composition, and you have maintained the KwieKulik materials for exhibition and reinterpretation. How has this labor of archiving changed for you over time? How have the historical materials from the KwieKulik period shifted in their substance or meaning as you have gone through major projects like the excellent monograph on your archive that was published in 2012?

ZK: In these questions I see also the question about my role in the KwieKulik duo. Other questions arise. Would any archive have existed if it was not Kwiek or not Kulik? Would the archive, as it was left by us around 1987 when we stopped our collaboration, would it be a public fact today if I did not labor on it during the last eight or nine years? Should I be unhappy that when I work on the archive I am not making my individual works? What even does “individual work” mean for me today? Should I sign my “reinterpretations” of KwieKulik materials with my name? Is it possible to “cultivate” two different biographies at the same time? (It is not simply a continuation.) My answers to these questions have not stabilized yet. I feel like a nurse for the KwieKulik achivement, and my later individual work is for me like a partner. Now I spend more time with the “patient” than with my partner.