The 2022 C-MAP seminar series, Transversal Orientations Part II, was held on Zoom across four panels on May 25 and 26, 2022. This text by writer, curator and art historian Sarah Lookofsky is the first in a series of written responses. The seminar series was organized by Nancy Dantas, C-MAP Africa Fellow, Inga Lāce, C-MAP Central and Eastern Europe Fellow, Madeline Murphy Turner, Former Cisneros Institute Research Fellow for Latin America, and Wong Binghao, C-MAP Asia Fellow.

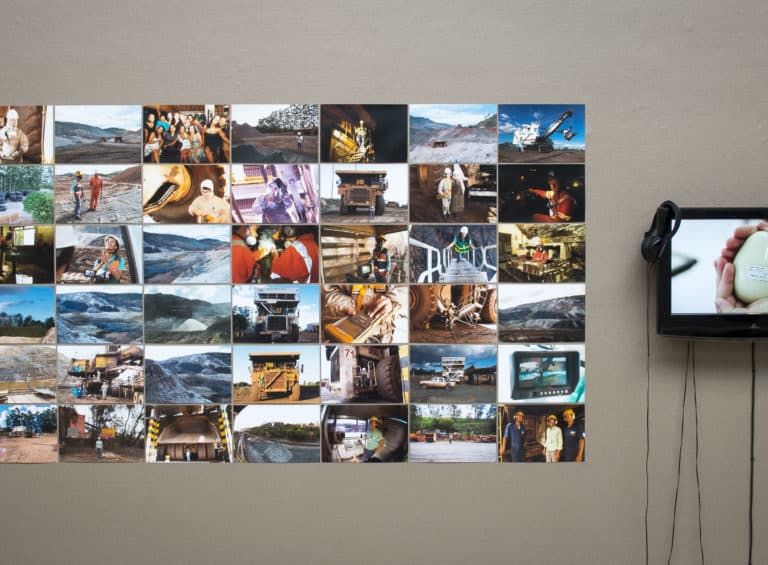

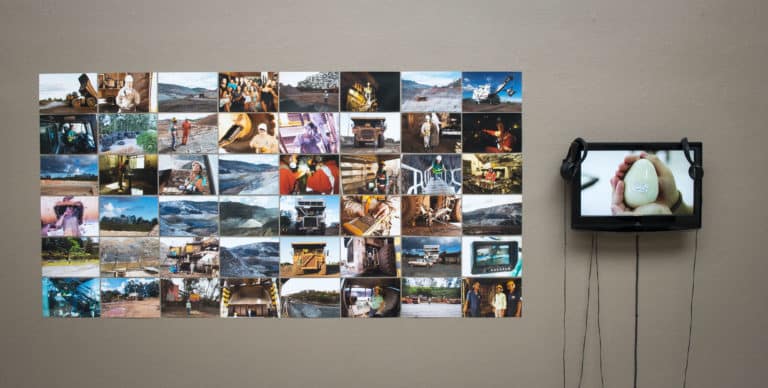

Juno Salazar Parreñas and Daniel Lie, Daiara Tukano and Nnenna Okore, in their practices and in the conversations that unfolded between them during the C-MAP seminar, engage more-than-human worlds, closely attuned to the relationships within them, and reaching across differences and disciplinary divides. Through specific in-depth emphases, they all carry memories and knowledge of historical damage and toxicities toward futurities, divergently imagined. These conversations made me think through, again but differently with the distance and learning that has transpired since a 2015 exhibition I co-organized at Aarhus Kunsthal with Elaine Gan and Steven Lam entitled DUMP! Multispecies Making and Unmaking“ (figs. 1-3, as above).1DUMP! Multispecies Making and Unmaking, 26.06.–20.09.2015, Kunsthal Aarhus website, https://www.kunsthalaarhus.dk/en/Exhibitions/Dump-Multispecies-Making-And-Unmaking-2015. DUMP! sought to think away from the primacy of making and production in the field of art, evoking the heap of decomposition and unruly combinations of Donna Haraway, but also the place where production becomes detritus: the trash heap of our contemporary anthropocenic present.2See Donna Jeanne Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). Alongside artworks, we included organisms and dumped a pile of wood chips (fig. 4, below) that was watered frequently (the Kunsthal graciously welcomed activities not normally allowed in a museum space) to invite fungal decomposition. A symposium that took place during the exhibition featured, among other things, culminations of collaborations between artists and scientists; a resumption of Cecilia Vicuña’s Semiya (fig. 5), a call for seeds originally proposed to Salvador Allende in 1971; a potato harvest (fig. 6, further down); a forage followed by a meal; a talk between anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing and biologist Jens Christian Svenning; and a reading group focused on The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K. Le Guin.3“DUMP! Workshop: Multispecies Making and Unmaking, September 5–6, 2015,” AURA: Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene, Aarhus University website, https://anthropocene.au.dk/conferences/dump-workshop-multispecies-making-and-unmaking-september-5-6-2015. The project sought to actively break down dichotomies and binaries—nature and culture, science and the humanities, wonder and comprehension, humans and more-than-humans—at the heart of historical hierarchies that have justified subordinations like white supremacy, man over matter, man over woman, and destructions wrought by colonialism and imperialism.

Despite the dissolution of boundaries that is so important to thinking through our present and to imagining a better future, I still find myself grappling with some key contradictions at the heart of ecological and environmental thought and the ways they are bound up with culture and art. These contradictions do not easily decompose in my mind, leaving me to alternate from one perspective to another in a movement that doesn’t seem conducive to reconciliation. The proposed methodology of transversalism of the C-MAP seminar does not deny differences but rather is preoccupied with weaving through them, and the sessions’ speakers demonstrated an investment in breaking down divisions while grappling with problems head on. With this background, I thought it would be a good exercise to focus on some of these contradictions as a way to reflect upon current practices and to acknowledge that when binaries are dissolved, the trajectory is not necessarily clear.4It is also a way, as Donna Haraway writes, of “staying with the trouble.” See Donna Jeanne Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

What follows is a calling out of three key contradictions that I find particularly pertinent to art’s embeddedness with various ecologies. In compiling this list, which is by no means all-encompassing or conclusive, I am indebted to many collaborators over the years and to the conversations between Salazar Parreñas, Lie, Tukano, and Okore in the C-MAP seminar.5In addition to the day’s panelists, this essay is informed by the work of contributors to a panel I organized as part of a prior C-MAP seminar “The Multiplication of Perspectives.” See Sarah Lookofsky et al., “The Planetary: The Globes of Globalization and Global Warming,” post: notes on art in a global context, May 6, 2020, https://post.moma.org/the-planetary-the-globes-of-globalization-and-global-warming/). It is also informed by a reading group organized under the auspices of the Cisneros Institute with Inés Katzenstein, Madeline Murphy Turner, and María del Carmen Carrión in the spring and summer of 2020 and by my own reading of many texts, but especially, Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 2 (2009): 197–222, https://doi.org/10.1086/596640, Most importantly, I want to acknowledge my continued and profound learning from Elaine Gan and Cecilia Vicuña. My thinking on this subject is in progress, and what follows will likely read as the exercise of writing-thinking that produced it: a dumpy dialectic.

The Damaged and the Pristine

DUMP! dwelled in the trash heap, thereby unwinding the logic of nature as pristine. A parallel site to that of the Kunsthal was Søby Brunkulslejerne, a deeply contaminated brown-coal mining site some 50 miles from the exhibition venue. Despite the focus on ecosystems affected by industrialization and colonialism, I still ponder how images conjuring landscapes without traces of modernity and colonialism at the same time can elicit fabulation and the imagination of better futures. Chief among the contradictions and contrasts that I find particularly sticky is that the capacity to think hope and healing on a damaged planet hinges on the ideas and imaginaries of precolonial, pre-destroyed landscapes. This amounts to so many national romantic imaginaries across the world, images that often accompanied colonial expansion and the destruction by industrialization of those landscapes, but also the sweeping vistas of screen savers and so many vacation photos that I too am guilty of perpetrating.

It is important to recognize the stronghold of the pre-destroyed or repaired landscape in the field of art. Art that deals with landscape inevitably comes to jostle with the histories of these imaginaries and the ways in which such images have been and continue to be conducive to a denial of the past and present damages and destructions induced by colonialism, imperialism, and modernity. Images of nature untouched also contribute to the marketing of landscapes, which have been completely altered by colonialism and conquest, for ecotourism that in turn further displaces the very populations who have historically inhabited the land.6For a useful analysis, including effects on cultural production, I have found the following especially useful: Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013). Ignoring histories of destruction and subordination, notions of the pristinely natural also belie the fact that every corner of the earth is affected by human intervention, whether visibly or not: microplastics are distributed everywhere, fusing with all bodies as well as geological material, just as the particles from prior nuclear detonations continue to circumnavigate the globe.7See Masco’s contribution to Lookofsky et al., “The Planetary.” These imaginaries also contribute to greenwashing and recycling that obfuscate the reality that nothing ever actually goes away; it just ends up broken down, redistributed, and somewhere else.

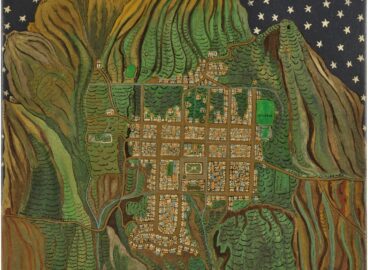

Colonial histories in relation to what came before them also resonates with the representation and inclusion of indigenous cultures in Western institutions. Activist and artist Daiara Tukano powerfully confronted the contemporary artworld’s gradual coming to terms with the historical exclusion of indigenous perspectives, including the fact that Western aesthetic categories have been intricately bound up with the construction of indigenous peoples as racialized and inferior. Such inclusions in Western presentational frames, as Tukano has called out, risk confining indigenous peoples and cultures to a historical past, banished from the present, and absorbed into the very systems of presentation and oppression that served colonialism and imperialism. Conversely, an approach that denies precolonial perspectives and notions of origin, integral to many indigenous cosmologies, risks occluding the valuable insights that these alternate ontologies hold for a future that is not dominated by extractivist, capitalist logics.8As Tukano seems to have inferred, it is important to stress how “decolonial” discourses within Western institutions diverge from practices of decolonization. See for example Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40, https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630. With the future of the Tukano people as stated objective, employing a counter-colonial methodology, Tukano articulated Western institutions as her first interlocutor, thereby flipping the script: rather than framing indigenous cultures in the manner of Western institutions, Tukano insisted on the West’s desperate need for a radically different framework, with coexistence at its heart, a prerequisite for more-than-human survival.

Omnipotence and Impotence

Another key contradiction that I find inextricably intertwined with questions of the environment and how it is perceived concerns the concept of human agency. Humans can be construed as piles of bacteria, and yet they can also be characterized as authors of nuclear detonations, oil spills, and carbon emissions. Despite some humans’ role in setting off chain reactions of environmental destruction, the processes in motion are beyond human control. Global warming, though propelled by industrial processes, has created a multitude of effects that humans do not steer, just as the coronavirus, likely caused by the human-driven destruction of habitats, has killed millions of people on the planet.9See https://covid19.who.int./ An important political problem at the crux of these contradictions has to do with the potential for humans to change the course of this chain of events—logics that typically rely on flawed characterizations of human agency and omnipotence by ignoring that we are inseparably linked to other species and our surrounding environment.

Along this jagged contradictory line, it was perhaps at the moment when the climate crisis was presented as “fixable”—a hole in the ozone layer to be patched—that the environmental movement in the West was born. Scientific approaches to encountering the world tend to double down on human-centric views—the very conceptions that must be overturned in order to address the crisis that the planet’s beings are currently facing. Inversely, conceptions that present all beings as equals (both between species and among humans) risk disavowing the hierarchies that have served to fix some species and human beings as subservient and inferior, and the fact that only some have done the most harm.

In art, the logics of individual agency and autonomy have been central to artistic practice and they have engendered ideological constructions of individuals as separate from one another and the world, mischaracterizing the complex webs from which humans cannot be torn. Nevertheless, artists have produced work that effectively decenters humankind, opening up production and reception to other makers and species communities. Such is the case of Åsa Sonjasdotter and her contribution to DUMP! (fig. 6), which featured photographs from the Groß Lüsewitz Breeding Institute in East Germany, an entity initiated by the Soviet Union in 1948, and renamed the Institute for Potato Research in 1968, where the Adretta potato variety was first developed. In the 1990s, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, former employees of the Institute established a company, utilizing research gained and patenting the potato, which continues to be planted by small farms. For the show, the potato grew, with watering support, in the Kunsthal courtyard. Pawel Wojtasik’s film Naked (2006) (fig. 7) shows a colony of mole rats living in a laboratory at a major American university. Due to human meddling, the mole rat is the most inbred species on the planet and has the longest lifespan of any laboratory animal of its size. The film gets up close, following the animals’ lives in detail and their otherwise overlooked socialities in—and in spite of—their captivity.

While creation and production is increasingly acknowledged as being the work of many actors, including the more-than-human collaboration, the aesthetic experience and perception nevertheless often seem to default to the individual realm, of one aesthetic experience isolated and against the next. To my mind, it is important for art to think through whether perception and experience can be conceived beyond solipsism.

Sense and Nonsense

Representation and signification are pivotal to art, and yet it is important to recognize that they are also distancing mechanisms, pulling us away from matter. Central to the question of expanding our frame beyond the human is to reckon with the fact that the privileged modes of human perception and communication, sight and language, cannot be relied upon for properly experiencing, accounting for, and relating to the world. There is great risk when human perception and modes of understanding come to guide environmental action, and thus when human cognition and prioritizations are projected onto other species and ecosystems. In crossing barriers of intelligibility and communication, there is always a real threat of domination and violence, of giving what is not desired or needed—a gift that might be tantamount to harm.10The violence often lodged within interspecies care relationships is beautifully unpacked in the work of Juno Salazar Parreñas. Sight is a notoriously flawed mode for producing understanding and signification can obstruct more-than-human perspectives and material ways of knowing. Indeed, so much of the world cannot be grasped by vision and language alone. All the senses must be taken into account in order to fully perceive the world we inhabit, and nonverbal communications needs to be appreciated as equally relational. It is also crucial to acknowledge that multitudes are unknown or not yet known as a step toward countering human delusions of omnipotence. Moreover, vision has been historically bound up with distance and separation and is intrinsically linked to Western epistemologies’ privileging of surface and appearance. The conception of appearance as a depth relation has importantly been instrumental in the logics of racism, white supremacist hierarchies and extractivism.

While language is exclusionary and denies other species the right to speak, one cannot deny that it is the default means of communication among humans, who hold the capacity to both produce and prevent destruction at great scales. And despite the powerful role scientific practices have played in colonial invasion, conquest, and extermination, methods of empirical observation, classification, and analyses still hold important possibilities for gaining knowledge and understanding of other species, across lines of difference. Mycology, the study of fungi, for instance, has opened up so many ways of breaking down habitual binary understandings (life and death, creation and destruction, gendered constructions, and more). Furthermore, scientific discoveries are, as artist and poet Cecilia Vicuña calls attention to, often in alignment with indigenous cosmologies and material knowledges.11Cecilia Vicuña and Sarah Lookofsky, Multispecies Worldbuilding Lab (blog), Episode 9, June 23, 2021, https://multispeciesworldbuilding.com/vicunia-lookofsky/.

Art sits fitfully within this space, between histories of depiction and signification and what cannot be codified, represented, communicated. All of the speakers provided openings into this field: Daniel Lie spoke about situating their practice within “the other-than-you-other-than-me”; Daiara Tukano addressed the nonhuman as a key interlocutor and the centrality of cosmovisions to her practice; Nnenna Okore invoked Ibo call-and-response and speaking beyond the human as a background for her work; Salazar Parreñas addressed the unknowability of orangutan desires as a framework that acknowledges incommensurability as well as codependence. As I listened, binaries were dismantled but contradictions sprouted and blossomed; questions led to more wonder.

DUMP! sought to decenter representation and signification as the primary modes of exhibition-making. It aimed to bring in materialities that could be experienced through different sensorial means. To this effect, Vicuña’s Semiya (figs. 8-9) included seeds collected by the artist in Chile as well as seeds brought to the exhibition by visitors. These were studied carefully through magnifying glasses, their minute scale enlarged and reminiscent of constellations holding the enormity of galaxies. The transversal proposes for us a perspective that allows us to think across distance, through the near and the far, perhaps even allowing us to connect the minute with the majestic. Nestled within this methodology, and pertaining to perception and communication, too, is the conundrum of solidarity on a planetary scale. Broaching vast distances clashes with the learned experience that knowing and communication, despite technological advancements, still relies on sensing, nonverbal communication and listening in the near. To address these planetary crises necessitates encounter and meeting, best up close, which paradoxically accelerates the crisis on our hands.

- 1DUMP! Multispecies Making and Unmaking, 26.06.–20.09.2015, Kunsthal Aarhus website, https://www.kunsthalaarhus.dk/en/Exhibitions/Dump-Multispecies-Making-And-Unmaking-2015.

- 2See Donna Jeanne Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

- 3“DUMP! Workshop: Multispecies Making and Unmaking, September 5–6, 2015,” AURA: Aarhus University Research on the Anthropocene, Aarhus University website, https://anthropocene.au.dk/conferences/dump-workshop-multispecies-making-and-unmaking-september-5-6-2015.

- 4

- 5In addition to the day’s panelists, this essay is informed by the work of contributors to a panel I organized as part of a prior C-MAP seminar “The Multiplication of Perspectives.” See Sarah Lookofsky et al., “The Planetary: The Globes of Globalization and Global Warming,” post: notes on art in a global context, May 6, 2020, https://post.moma.org/the-planetary-the-globes-of-globalization-and-global-warming/). It is also informed by a reading group organized under the auspices of the Cisneros Institute with Inés Katzenstein, Madeline Murphy Turner, and María del Carmen Carrión in the spring and summer of 2020 and by my own reading of many texts, but especially, Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 2 (2009): 197–222, https://doi.org/10.1086/596640, Most importantly, I want to acknowledge my continued and profound learning from Elaine Gan and Cecilia Vicuña.

- 6

- 7See Masco’s contribution to Lookofsky et al., “The Planetary.”

- 8As Tukano seems to have inferred, it is important to stress how “decolonial” discourses within Western institutions diverge from practices of decolonization. See for example Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–40, https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

- 9See https://covid19.who.int./

- 10The violence often lodged within interspecies care relationships is beautifully unpacked in the work of Juno Salazar Parreñas.

- 11Cecilia Vicuña and Sarah Lookofsky, Multispecies Worldbuilding Lab (blog), Episode 9, June 23, 2021, https://multispeciesworldbuilding.com/vicunia-lookofsky/.