In this essay, Andra Silapētere introduces two key figures of the Hell’s Kitchen group of Latvian exile artists in New York. The work of the group will be featured in an exhibition this November at James Gallery of the CUNY Graduate Center as part of a series of exhibitions on Latvian emigrant artistic communities, Portable Landscapes, organized by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art.

The history of Baltic art during the Soviet era (1944–1991) has been reconsidered by re-evaluating the socialist legacy and its multifaceted art scene via local and regional studies, exhibitions, and conferences. But looking more closely at the period reveals a much more complex landscape, where alongside the art processes taking place in the Soviet Union, a parallel history of Baltic art and culture was being formed on the other side of the Iron Curtain. The Soviet occupation drove many artists into exile,

1In 1944, fearing continued Soviet repression, hundreds of thousands of people left the Baltic states. They travelled to Western Europe, and most people ended up in Germany, where they spent years in Displaced Person Camps (1945–1949) established primarily for refugees from Eastern Europe after World War II by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The camps were divided into Allied occupation zones: French, American, British, and Soviet. To deal with the post-war refugee crises, a number of countries signed draft laws that allowed the refugees to start new lives via further emigration. Beginning in 1948, Baltic refugees emigrated to Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and South America, among other places. but the resulting exile and diaspora art has been little discussed over the years. Exiled artists are still passed over, and their work not adequately considered in the development of interpretations of Eastern European art history. To highlight this overlooked legacy, the research project “Portable Landscapes,” initiated by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art, examines the histories within Latvian exile and emigrant artist communities from the beginning of the twentieth century to the present. The project aims to reintroduce exile art to local and regional art history writing as well as to contribute to the understanding of border art events of the twentieth century.

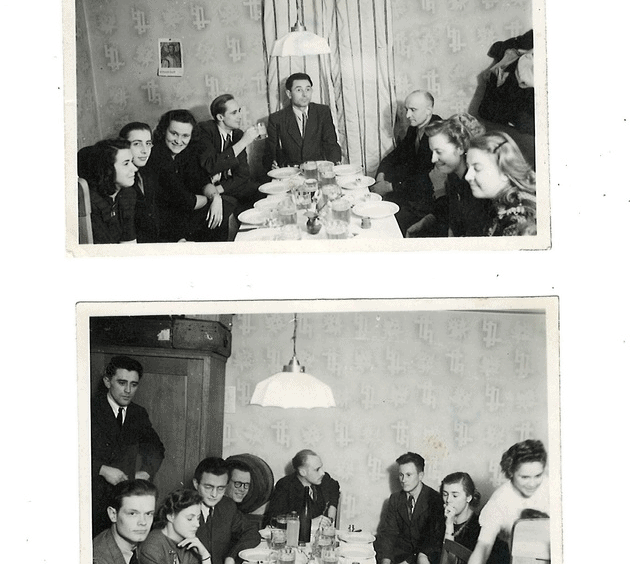

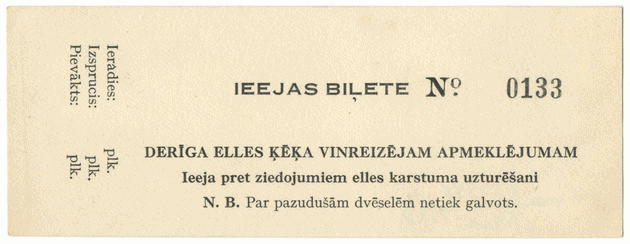

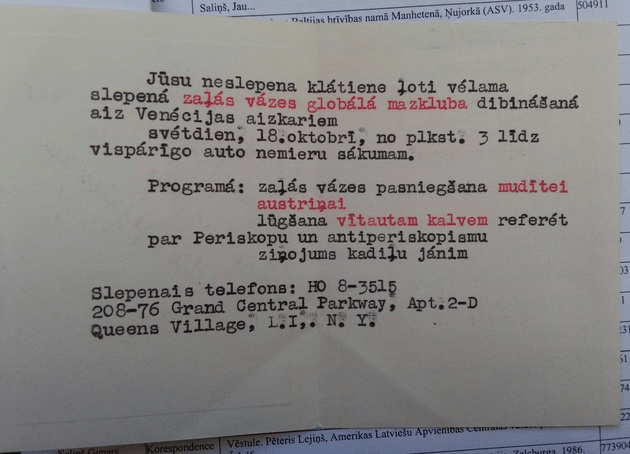

One of the histories reconsidered in this research is the artist and literary collective Hell’s Kitchen, which was active in New York from the 1950s through the 1970s. The group combined visual art and text-based practices, bringing together more than fifteen artists, writers, and literary scholars on an on-again, off-again basis.2Poets Gunars Saliņš, Linards Tauns, Jānis Krēsliņš, Teodors Zeltiņš, Roberts Mūks, Aina Kraujiete, Rita Gāle, and Baiba Bičole; writer Mudīte Austriņa; literary scholar Jautrīte Saliņa; writer and parapsychologist Kārlis Osītis; literary critic Vitauts Kalve; and artists Frīdrihs Milts, Sigurds Vīdzirkste, Ronalds Kaņeps, Daina Dagnija, Ilmārs Rumpēters, Voldemārs Avens, and Klāra Zāle. They associated themselves with Hell’s Kitchen, a neighbourhood on Manhattan’s West Side, where they most often met to organize poetry readings and performance events that brought identity issues into high relief within the contexts of exile and migration as the two related to the group members’ own experiences. Unfortunately, their collective activities were never systematically documented, but tracing the individual archives of group members in Latvia and the United States allowed to reconstruct the group’s history and to map the questions important to their creative expression. The group adopted exile and displacement as their main focus as a collective—and in their work as individuals. Activating their historical and cultural knowledge, and in that way distancing themselves from their new environment and the art scene undertaken there, they constructed new meanings and alternative forms of expression. To shed light on what was, from the perspective of the exiled artist, essentially a parallel infrastructure within the New York art scene, I will discuss two group members, in particular: the writer Mudīte Austriņa (1924–1991) and the painter Sigurds Vīdzikste (1928–1974).

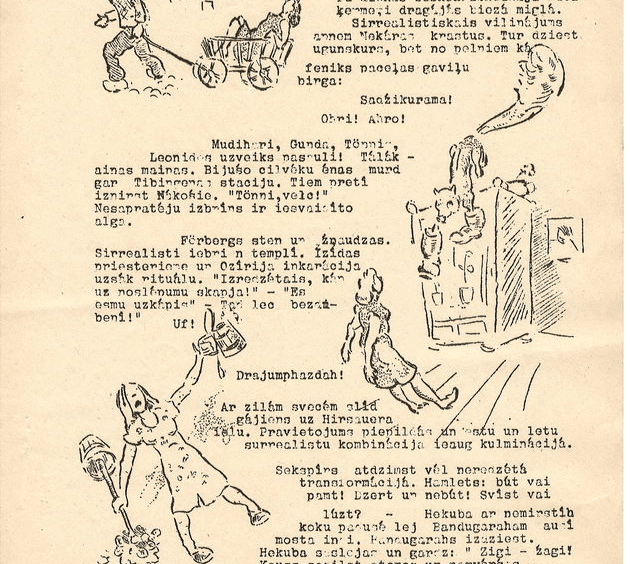

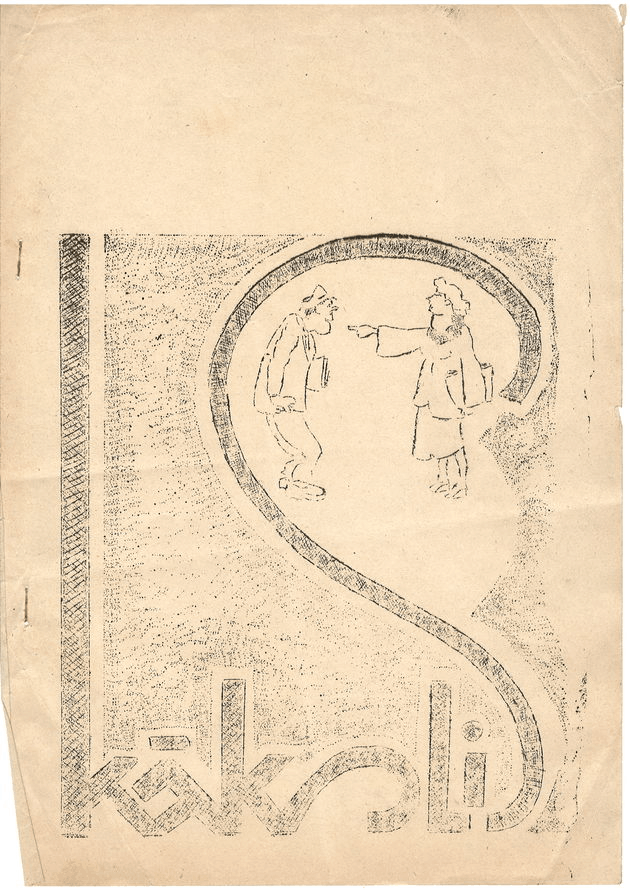

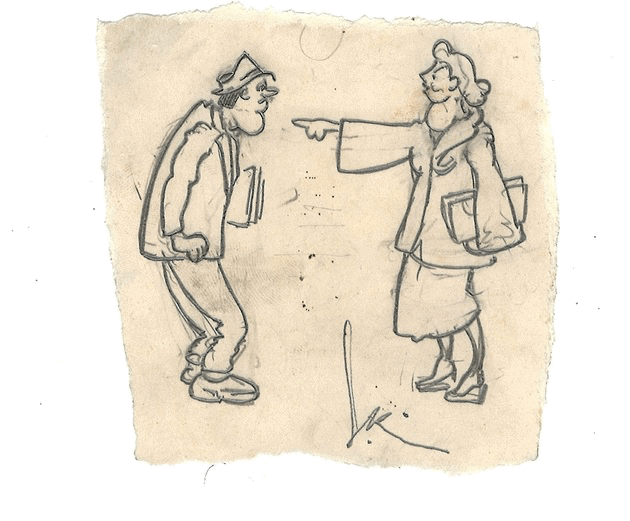

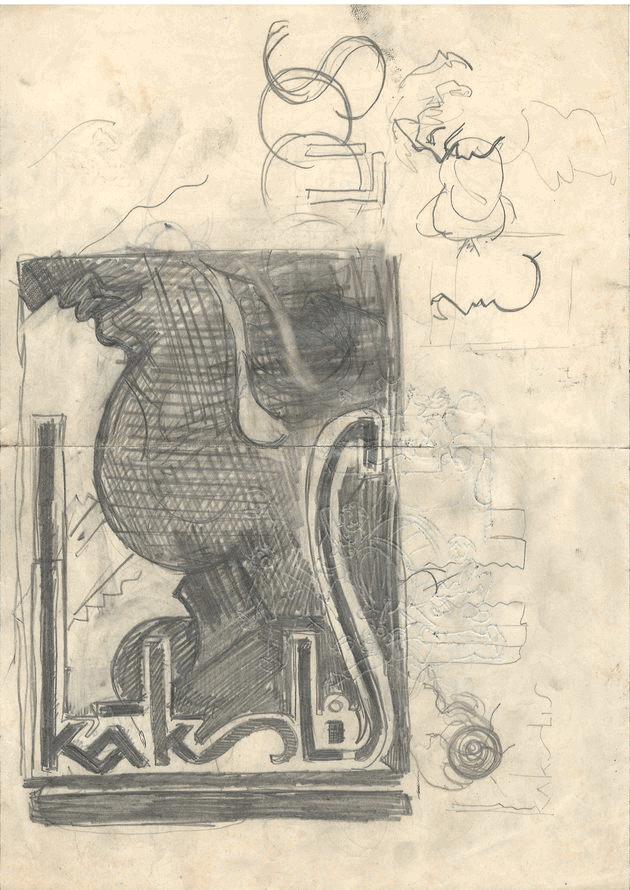

Information about the formation of the Hell’s Kitchen collective is limited, leaving much room for speculation, but the origins of the collective are linked to Tübingen, a university town in southern Germany, where around 1946, a group of Latvians began their studies after being forced to leave their own country. Rare evidence of their shared interest includes the two samizdat magazines Mīstiklas (1946) and Kākslis(1948), where with irony and humor, young writers and artists commented on the harsh realities of migrant and student life in Germany.3The titles of the magazines use old forms of Latvian words as metaphors for the messages delivered by the magazines. The “Mīstiklas” is an instrument used for linen and hemp cultivation, and in the context of the magazine title, suggests the harsh reality of student life, “Kākslis” translates as Adam’s apple and can be interpreted as a loudspeaker. Despite the serious nature of the subject, both publications reveal creativity and humor as important tools in overcoming the trauma associated with forced emigration. These tools were also vital components to the group in New York City, where the formation of the collective, as it is considered today, took place sometime after 1948, when the Displaced Persons Act was signed into law, and refugees from Europe were admitted into the United States.4On June 25, 1948, US president Harry Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act, which allowed political refugees from Europe to immigrate to the United States, and many Baltic refugees subsequently chose the economically thriving United States as their new homeland. The group in New York developed as a dynamic unit in their stance against rigid social norms and rationalism. This self-declared opposition was a reaction to the exile situation they were facing and was at odds with the ideas prevailing in the Latvian diaspora, which was generally more prone to conservatism.5An evident part of the Latvian diaspora in the United States was culturally conservative and nationally oriented, stimulated by a belief during the 1950s that there was a possibility of return in the not-too-distant future, a sense of duty toward occupied Latvia and the people who remained there, and a sense of obligation to nurture Latvia outside Latvia.

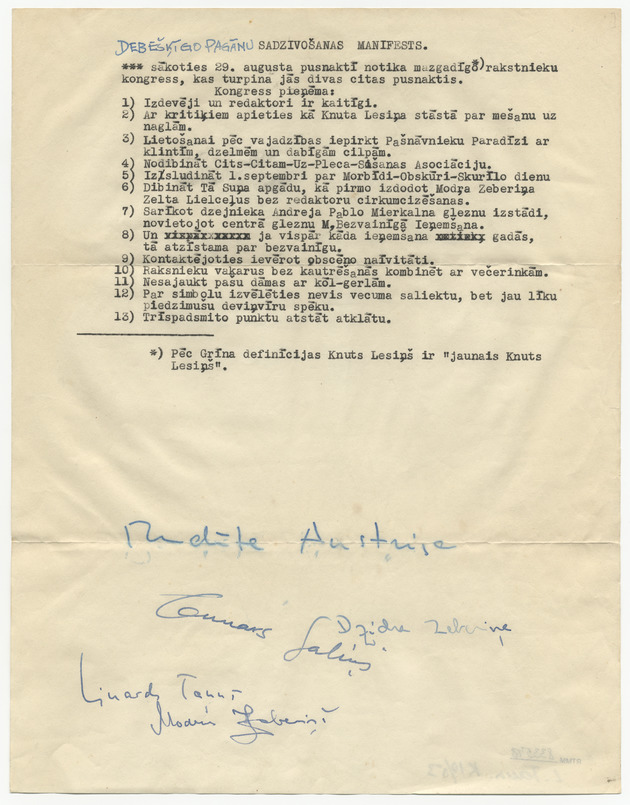

For “Heavenly Pagans,” as group members called themselves, the collective served as a laboratory that stimulated their individual work, creating a platform for collaborations and a context in which they were able to strengthen their positions in the art world and put forward their ideas in their new environment.6The group’s activities reached a peak in the end of the 1950s, but slowed down after 1963, when the poet Linards Tauns, one of its core members, unexpectedly died. The intellectual climate grew quieter, and yet an intense exchange of ideas still continued through organized gatherings and events. A statement of their philosophy, their “Heavenly Pagan Cohabitation Manifesto” (1956) contains thirteen points that, written with a great deal of absurdity and humor, demonstrate the group’s creative approaches to the realities they were facing as young artists in exile: the complexity of getting their work published in the United States and the need for support from colleagues. In this context, their Latvian language and national identity were important points of reference in their creative production—despite their willingness to be integrated into the local art world and culture. Most of their writings and organized events were in Latvian, which could be interpreted as a rejection of their new context and obstinacy in terms of needing to prove their existence as a distinct community within the multicultural New York City environment. But within the context of their displacement, it can also be interpreted as a hybrid form of self-historicizing in the international art system of which they were part. Pushed to search for their own historical, social, and cultural context within a new country, they found identity and language to be important tools in developing their collective history and establishing their own autonomous territory, one in which they could document and interpret their experiences. In this way, language, historical experience, and identity served not only as identifying, but also as historicizing elements.

Mudīte Austriņa: Surrealism as a Catalyst for Exile Experience

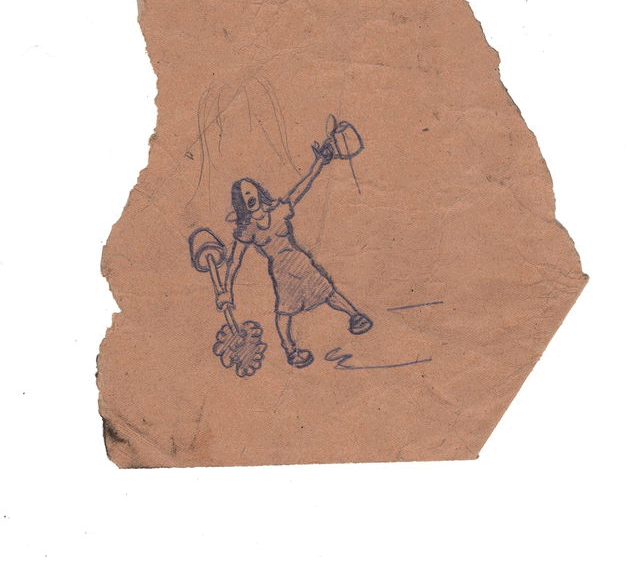

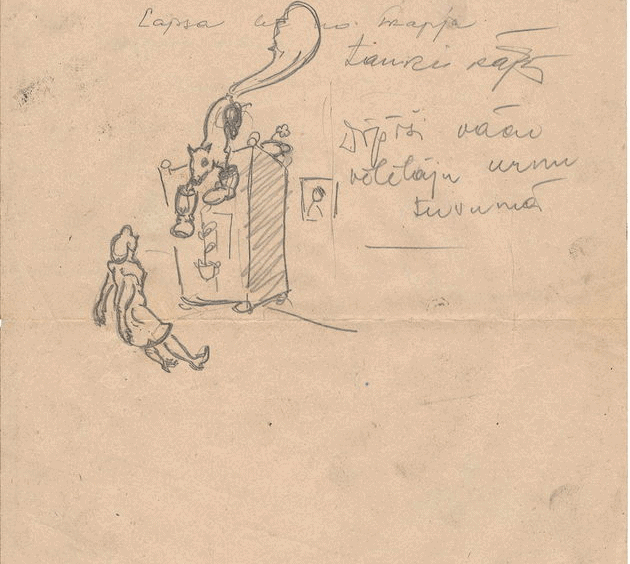

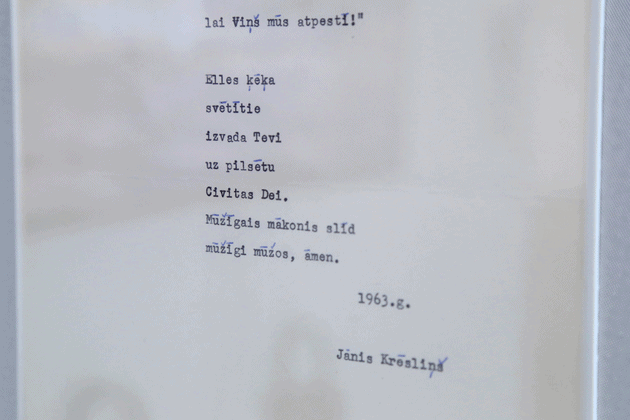

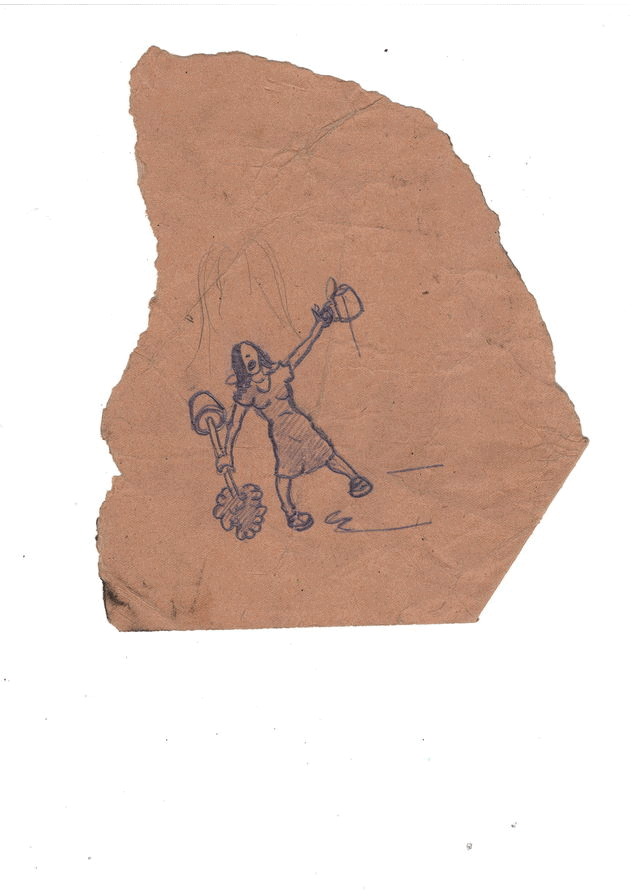

The work of the writer Mudīte Austriņa, one of the main initiators of the group’s activities, illustrates such self-historicizing. Her creative interests were broad, but surrealist art and literature were especially important to her, both aesthetically and conceptually. Austriņas’s interest in surrealism began while she was studying art history at the University of Tübingen, but the city’s cultural environment contributed to its development. Tübingen was part of the French occupation zone, and so French culture was very strong: bookshops sold French literature, the cinemas showed French movies, and visiting theater troupes from Paris regularly performed. The cultural atmosphere as well as her knowledge of the French language stimulated in her a deeper study of French literature, especially with regards to the work of André Breton. In the magazine Kākslis (1948), one of her first surrealist expressions, describes a poem written by long-term group member Jānis Krēsliņš (born 1924) entitled “Surrealist Movement in Tübingen.”7The poem was written by Jānis Krēsliņš under the pseudonym Zans Mijkrēslis. It mentions the following people as actively participating in the walks: Mudihari (Mudīte Austriņa), Gunda (Renāte Grāve, Austriņas’s roommate), Tonis (a friend of the group and a student from Estonia), and Leonidas (an unknown person). It describes “Two violet hat days,” performances in which participants wearing violet accessories strolled through the city and then engaged in poetry readings. Unfortunately, not much more is known about this event as it wasn’t documented. The quintessence of Austriņas’s surrealist expressions are her “baletiņi” (small ballets), or her short absurd scripts that she wrote in New York starting the 1950s as theatre plays or scenarios for short films. She built the main characters from the Hell’s Kitchen collectives’ personalities, looking at culture and identity in the context of exile—at its traumas and challenges—and documenting her own and her companions’ experiences in New York. These surrealist pieces can be interpreted as a means of escaping the traumas of exile and of dealing with displacement by irrationalizing it. Yet they also evoke the ambience of the group’s context of New York, an environment they saw as irrational—and their lack of a suitable social, political, and historical background within it, or a specificity that would have strengthened their position.

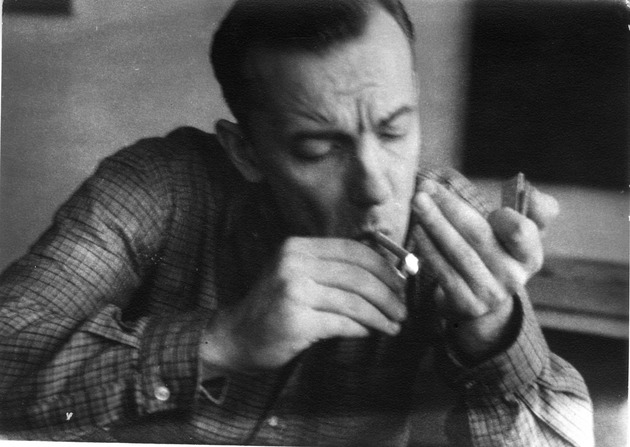

Sigurds Vīdzirkste: A Little-Known Contributor to Cybernetics in New York

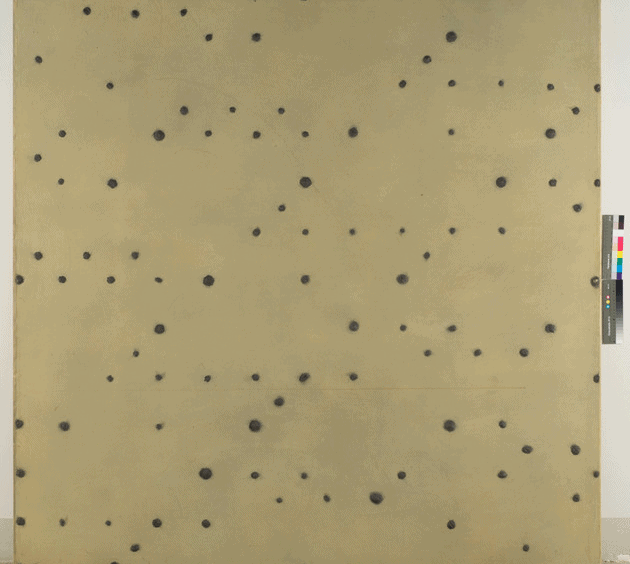

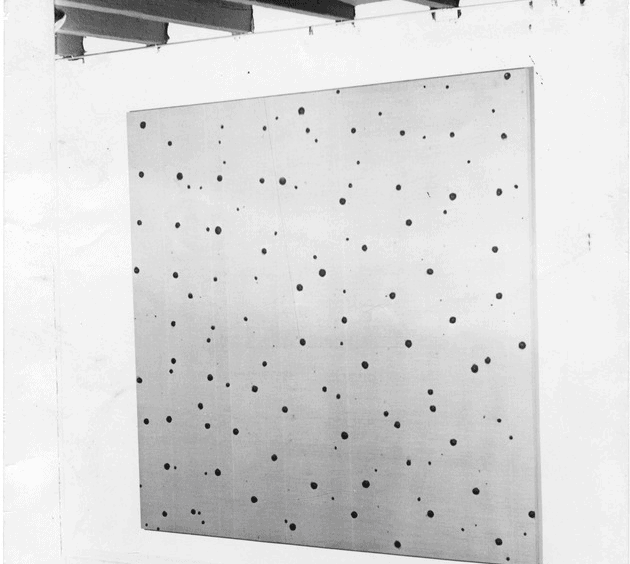

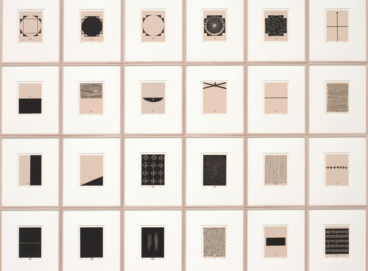

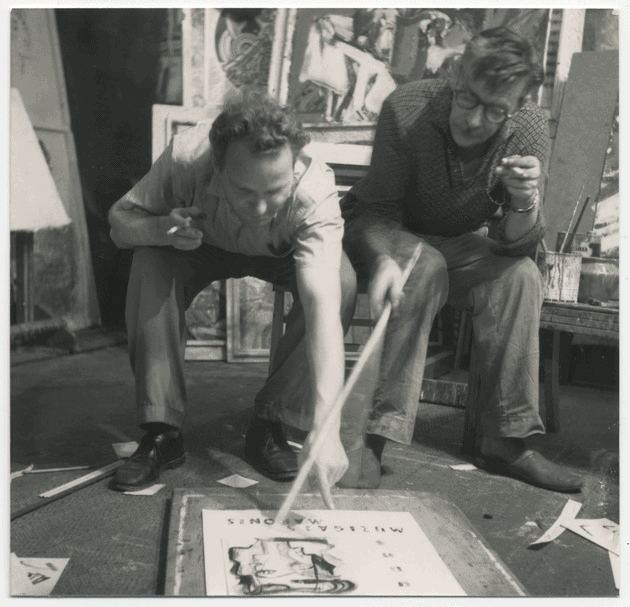

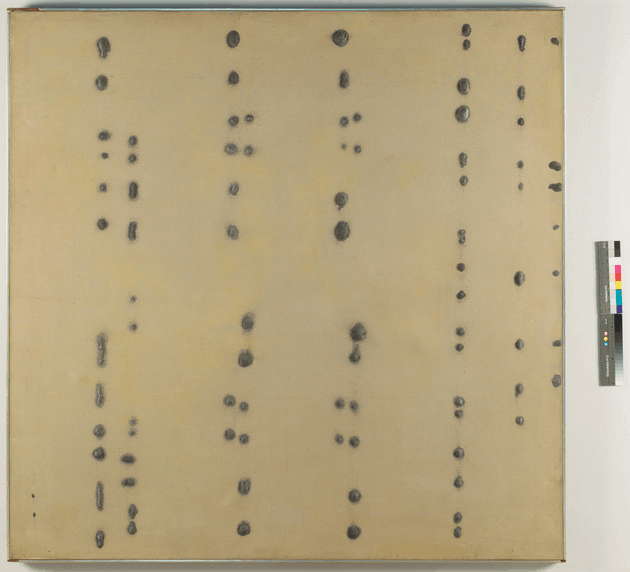

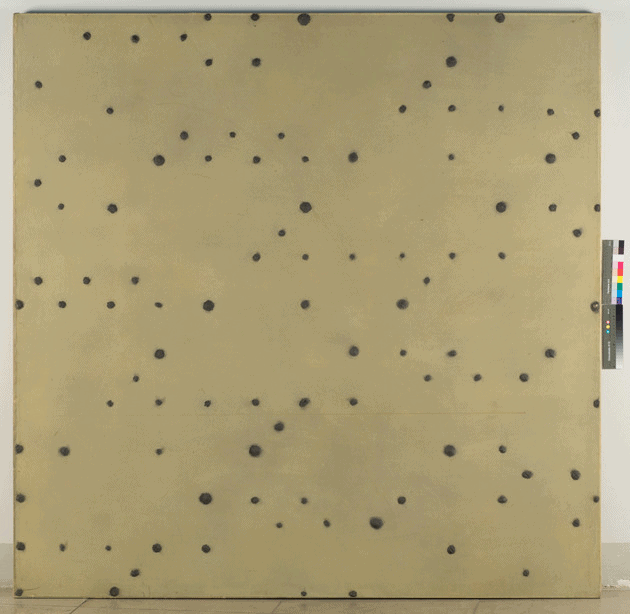

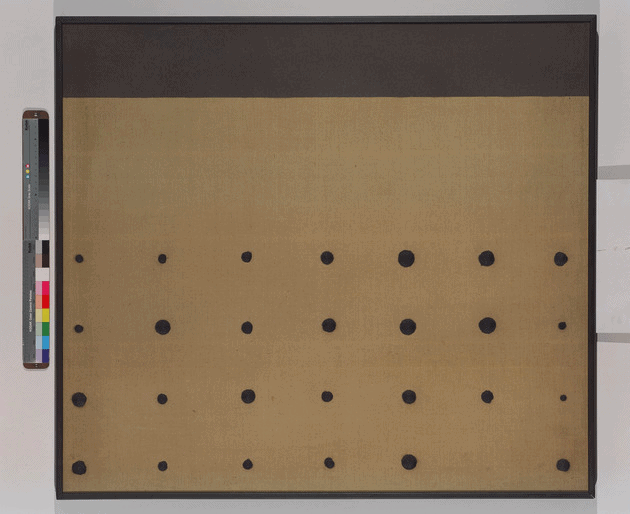

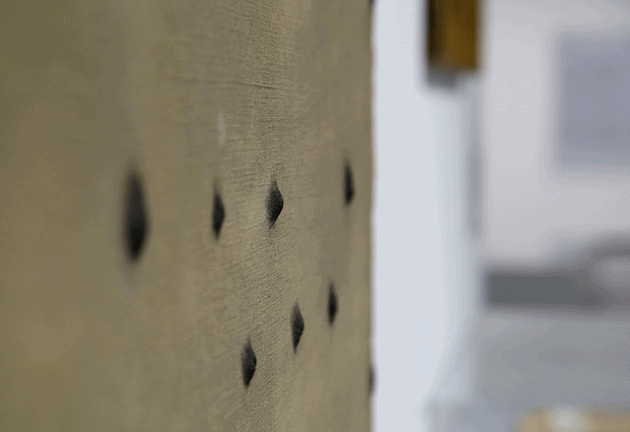

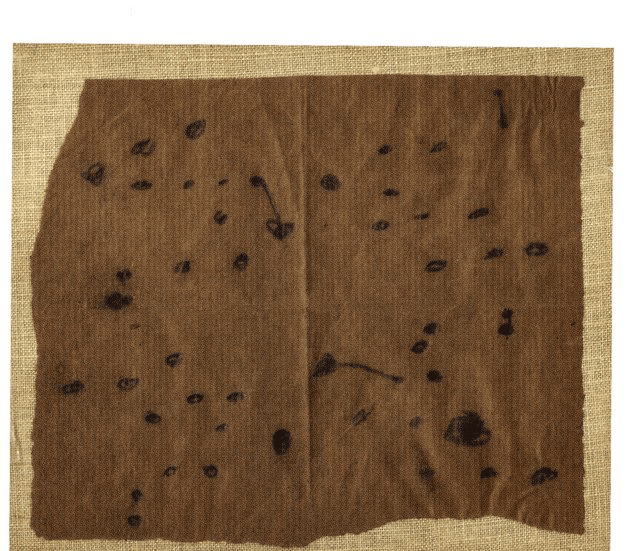

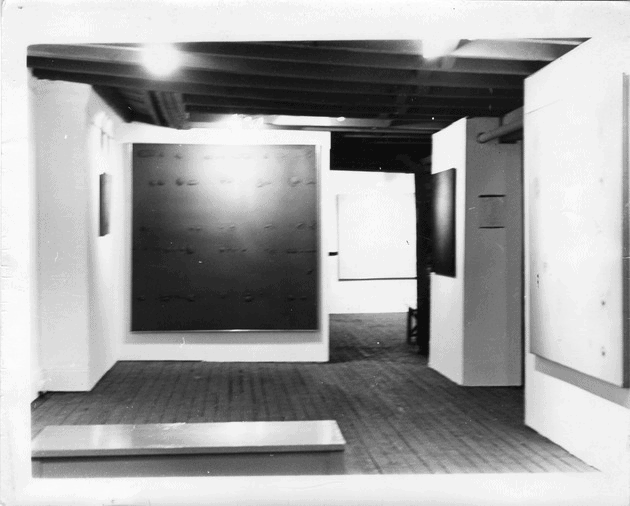

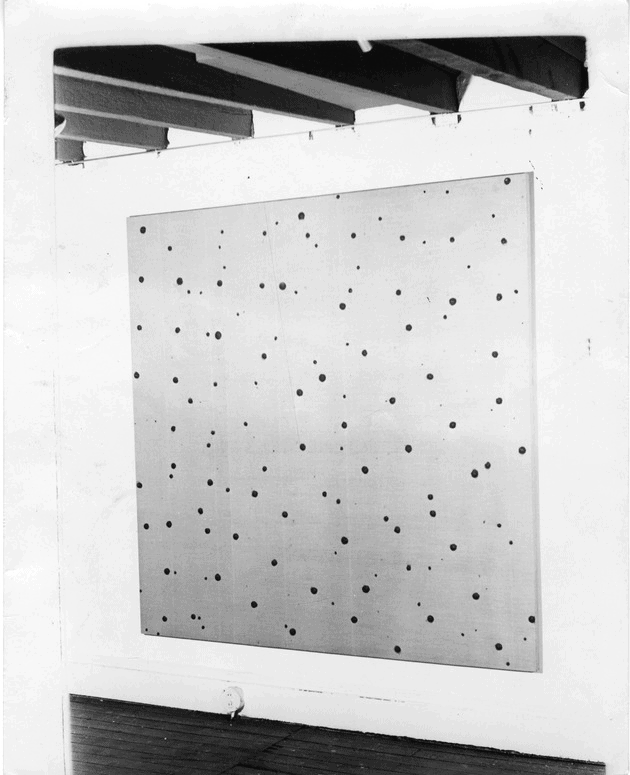

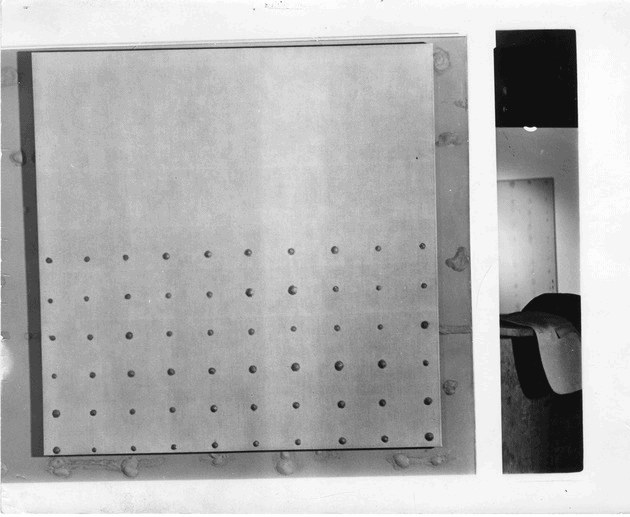

The painter Sigurds Vīdzirkste is another example of an artist in exile responding to the environment of the New York City art world by developing ideas outside of it, while nonetheless participating within it. Vīdzirkste constructed his artistic language by reacting to the rising interest in technology at that time, and through that, bringing artistic production to a new level. After his studies at the Art Students League, he developed a unique style of painting that he called “cyber-painting,” in which he synthesized his interests in mathematics, chemistry, and music. He first exhibited this work in 1964, in a solo show in his studio at 148 Liberty Street, where, next to abstract compositions of circles and stripes, he displayed canvas with dot-like reliefs, callous clots, and metallic-powder compressions organized in different rhythms.8Šturma, Elionora. (1964, 11 January) Divas skates. Laiks: 3. This show was followed in 1968 by a solo show entitled Cybernetic Canvases, which, held at the Kips Bay gallery at 613 Second Avenue, was the first time Vīdzirkste publicly used the term “cybernetics” in relation to his work.9Cybernetics is a transdisciplinary approach to exploring regulatory systems—their structures, constraints, and possibilities. American mathematician Norbert Wiener (1894–1964) defined the term in 1948, explaining it as a science of control and communication in the animal and the machine. All of the exhibited canvases were composed of relief dots on monochrome ochre or grey backgrounds, and they were untitled, undated, and unsigned; only a number was assigned to each work.

After Vīdzirkstes’s death in his studio in New York, different pots with metallic powder and toluene were found, and after his paintings were brought to Latvia, a chemical analysis of one of his works revealed a mixture of pigments—metal particles soaked in a chemical substance and mixed with resin and resin lacquer.10Unfortunately, only one painting made at the end of the 1950s was analyzed. To make broader conclusions about the development of Vīdzirkstes’s praxis and his materials would require examination of more of his work. Such combinations and experiments with pigments were most likely stimulated by his chemistry studies at the Riga State Secondary School before his emigration in 1944.

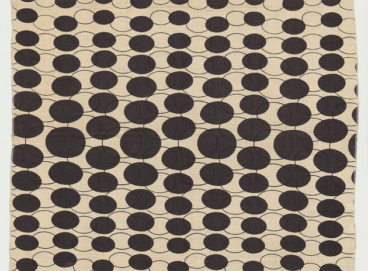

It is hard to trace a definite theory behind Vīdzirkstes’s dot paintings as he did not expand on his ideas in writing; but from sources available, we know that each work was created as an information system similar to that of punched cards for early digital computers.11The idea of programming was important to him, and since he worked at the Federal Reserve Bank as an audiovisual specialist, he had the opportunity to observe the calculating machines used by the bank. Other material in his archive shows his interest in the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716), who invented the calculating machine. See Vanaga, Anita. “Sigurda Vīdzirkstes kibernētiskā glezniecība. Pazaudētais kods” (“Sigurds Vīdzirkste’s Cybernetic Canvases: The Lost Code”), Mākslas vesture un teorija (Art History and Theory) 9 (2007): 35–44. With each new painting, the artist organized dots in different rhythms and sizes and, as Voldemārs Avens (born 1924), another member of the Hell’s Kitchen group, remembers, he used precise calculations to create each system.12From conversation with Voldemārs Avens, March 11, 2017. As part of his process, he layered dot drawings done on transparent plastic sheets to create variations of patterns that could later be transferred onto canvas. This brings us back to his 1964 show, in which he also exhibited three drawings, which according to Vīdzirkstes’s letter written to his parents, formed the base of his information systems. Unfortunately, only one of them can be found in his archive, making it impossible to break his code.

With the development of technology after World War II, the use of cybernetics in art was prevalent in Europe,13A significant manifestation of cybernetic and related technologies and their use in art was the 1968 exhibition Cybernetics Serendipity, curated by Jasia Reichardt at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. Another was the New Tendencies movement, which started in Zagreb, Croatia (former Yugoslavia) and was active in the 1960s and ’70s. Its proponents experimented with computers in art making and, in that way, anticipated new media and digital art. whereas in the United States, this was not the case. Even though one can map out early experiments linking art and technology, cybernetic and computational thinking in artistic production did not become widespread until the 1970s.14Examples include the series of performances known as 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering (1966), which was initiated by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver. Additionally, in 1968, György Kepes founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT to bring visual artists, including the pioneer of cybernetics sculpture in the United States Wen-Ying Tsai, Jack Burnham, Otto Piene, Takis, Harold Tovish, and Stan VanDerBeek, into contact with scientists and engineers. Also, one of the pioneering pieces using programming includes John Cage and Lejaren Hiller’s computer-generated composition HPSCHD (1969). Given this, Vīdzirkstes’s works developed in the 1960s, which demonstrate a unique and alternative system of visual signs bridging computing technologies and art, can be interpreted as a pioneering praxis that introduced the idea of programming to painting as a way to reconsider artistic production of the time.

~ Rethinking the group’s and its individuals’ history in New York allows us to expand our understanding of the processes that define Baltic art and culture during the Soviet era, and to map a more complete story of its global, regional, and national history. This re-examination reveals a parallel to and alternative facet of Baltic art of the second part of the twentieth century that was not only in dialogue with a global art scene, but was also confronted by an identity crisis that became a catalyst in creative production.

- 1In 1944, fearing continued Soviet repression, hundreds of thousands of people left the Baltic states. They travelled to Western Europe, and most people ended up in Germany, where they spent years in Displaced Person Camps (1945–1949) established primarily for refugees from Eastern Europe after World War II by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The camps were divided into Allied occupation zones: French, American, British, and Soviet. To deal with the post-war refugee crises, a number of countries signed draft laws that allowed the refugees to start new lives via further emigration. Beginning in 1948, Baltic refugees emigrated to Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, and South America, among other places.

- 2Poets Gunars Saliņš, Linards Tauns, Jānis Krēsliņš, Teodors Zeltiņš, Roberts Mūks, Aina Kraujiete, Rita Gāle, and Baiba Bičole; writer Mudīte Austriņa; literary scholar Jautrīte Saliņa; writer and parapsychologist Kārlis Osītis; literary critic Vitauts Kalve; and artists Frīdrihs Milts, Sigurds Vīdzirkste, Ronalds Kaņeps, Daina Dagnija, Ilmārs Rumpēters, Voldemārs Avens, and Klāra Zāle.

- 3The titles of the magazines use old forms of Latvian words as metaphors for the messages delivered by the magazines. The “Mīstiklas” is an instrument used for linen and hemp cultivation, and in the context of the magazine title, suggests the harsh reality of student life, “Kākslis” translates as Adam’s apple and can be interpreted as a loudspeaker.

- 4On June 25, 1948, US president Harry Truman signed the Displaced Persons Act, which allowed political refugees from Europe to immigrate to the United States, and many Baltic refugees subsequently chose the economically thriving United States as their new homeland.

- 5An evident part of the Latvian diaspora in the United States was culturally conservative and nationally oriented, stimulated by a belief during the 1950s that there was a possibility of return in the not-too-distant future, a sense of duty toward occupied Latvia and the people who remained there, and a sense of obligation to nurture Latvia outside Latvia.

- 6The group’s activities reached a peak in the end of the 1950s, but slowed down after 1963, when the poet Linards Tauns, one of its core members, unexpectedly died. The intellectual climate grew quieter, and yet an intense exchange of ideas still continued through organized gatherings and events.

- 7The poem was written by Jānis Krēsliņš under the pseudonym Zans Mijkrēslis. It mentions the following people as actively participating in the walks: Mudihari (Mudīte Austriņa), Gunda (Renāte Grāve, Austriņas’s roommate), Tonis (a friend of the group and a student from Estonia), and Leonidas (an unknown person).

- 8Šturma, Elionora. (1964, 11 January) Divas skates. Laiks: 3.

- 9Cybernetics is a transdisciplinary approach to exploring regulatory systems—their structures, constraints, and possibilities. American mathematician Norbert Wiener (1894–1964) defined the term in 1948, explaining it as a science of control and communication in the animal and the machine.

- 10Unfortunately, only one painting made at the end of the 1950s was analyzed. To make broader conclusions about the development of Vīdzirkstes’s praxis and his materials would require examination of more of his work.

- 11The idea of programming was important to him, and since he worked at the Federal Reserve Bank as an audiovisual specialist, he had the opportunity to observe the calculating machines used by the bank. Other material in his archive shows his interest in the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716), who invented the calculating machine. See Vanaga, Anita. “Sigurda Vīdzirkstes kibernētiskā glezniecība. Pazaudētais kods” (“Sigurds Vīdzirkste’s Cybernetic Canvases: The Lost Code”), Mākslas vesture un teorija (Art History and Theory) 9 (2007): 35–44.

- 12From conversation with Voldemārs Avens, March 11, 2017.

- 13A significant manifestation of cybernetic and related technologies and their use in art was the 1968 exhibition Cybernetics Serendipity, curated by Jasia Reichardt at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. Another was the New Tendencies movement, which started in Zagreb, Croatia (former Yugoslavia) and was active in the 1960s and ’70s. Its proponents experimented with computers in art making and, in that way, anticipated new media and digital art.

- 14Examples include the series of performances known as 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering (1966), which was initiated by Robert Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver. Additionally, in 1968, György Kepes founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies (CAVS) at MIT to bring visual artists, including the pioneer of cybernetics sculpture in the United States Wen-Ying Tsai, Jack Burnham, Otto Piene, Takis, Harold Tovish, and Stan VanDerBeek, into contact with scientists and engineers. Also, one of the pioneering pieces using programming includes John Cage and Lejaren Hiller’s computer-generated composition HPSCHD (1969).