Art historian Inesa Brašiškė highlights the ideas behind the work of Lithuanian-American artist and architect Aleksandra Kasuba (1923–2019), most notably her countering of the rigid geometry of architecture through the use of soft materials and curved shapes, and her emphasis on the fundamental connection between the built environment and the formation of subject. Kasuba’s work has been a major inspiration to Lithuanian artist and filmmaker Emilija Škarnulytė (1987), most recently in an exhibition project Circular Time. For Aleksandra Kasuba, which accompanied an exhibition of Kasuba’s work at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius, and is discussed in a recent conversation with Škarnulytė published by post.

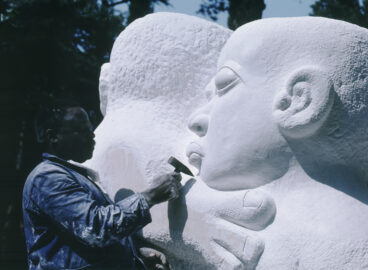

The work of Lithuanian-born artist and architect Aleksandra Kasuba (1923–2019) merges architecture, sculpture, and craft, rotating around a central concern with space. Developed over several decades in Kasuba’s adopted home of New York City, and culminating in a last major endeavor in New Mexico, much of this artistic output was recently highlighted in a retrospective exhibition curated by Lithuanian art historian Elona Lubytė at the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius. Kasuba’s artistic and archival legacy, which consists of monumental decorative works for public spaces, fabric environments, and models, drawings, and collages of never-realized projects for dwellings, reveals a persistent artistic vision. The conviction at the core of Kasuba’s space-making endeavors—that there is a fundamental correlation between the subject’s formation and the built environment—opens up multiple avenues worth revisiting.

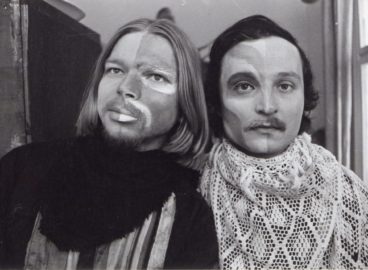

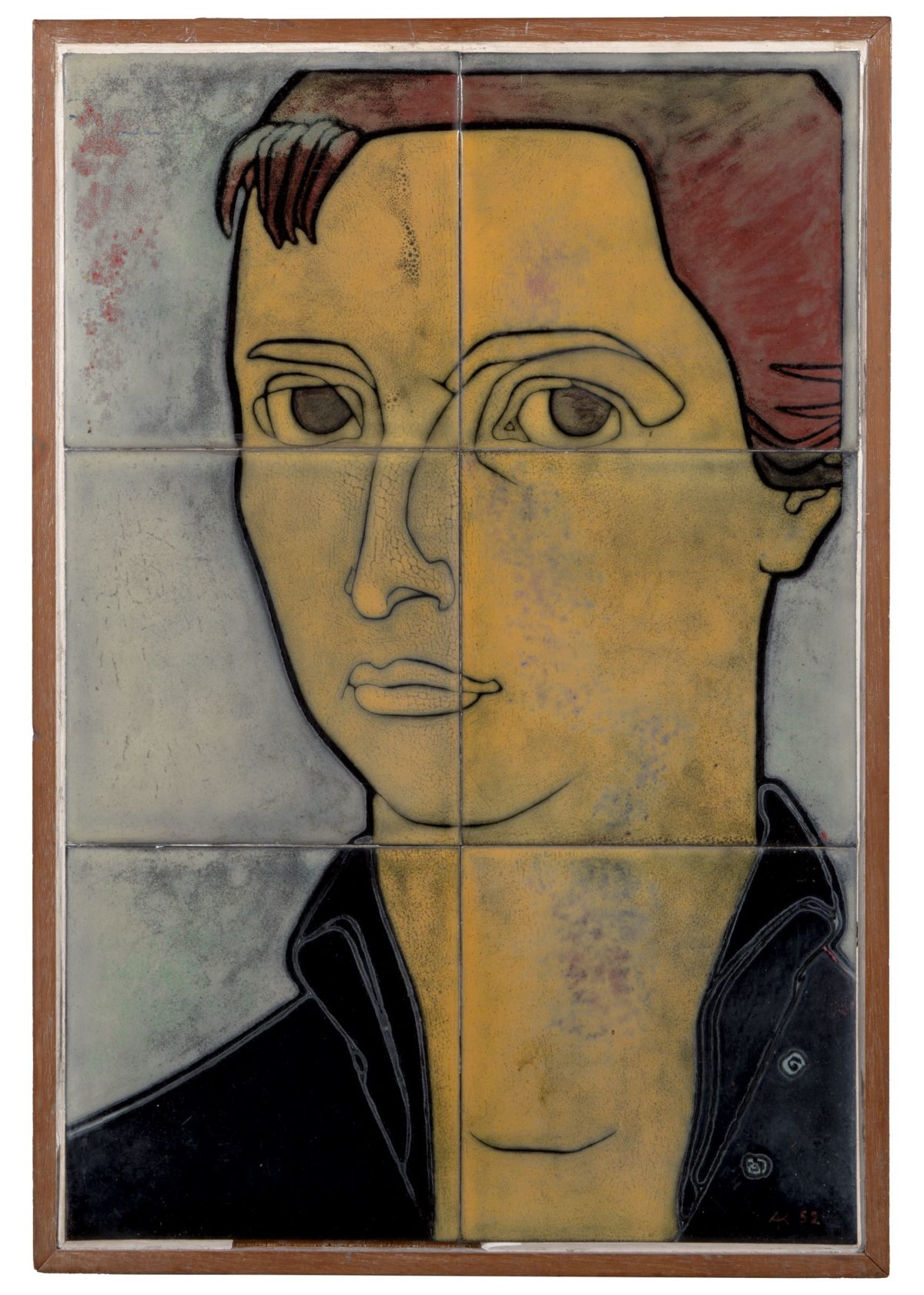

Born into an aristocratic family with progressive leanings, Aleksandra Kasuba (née Fledžinskaitė) attended the gymnasium in Šiauliai, Lithuania, where one of her teachers was the semiotician Algirdas Julius Greimas.1Kasuba resumed an intellectual dialogue with Algirdas Julius Greimas late in her life. Correspondence between Greimas and Kasuba is published in Algirdo Juliaus Greimo ir Aleksandros Kašubienės Laiškai, 1988–1992 (Vilnius: Baltų lankų leidyba, 2008). Her brief studies in sculpture in Kaunas and Vilnius, respectively, were interrupted by the Nazi and Soviet occupations that ultimately forced many Lithuanians, including Kasuba and her husband, Lithuanian sculptor Vytautas Kasuba (1915–1997), to flee to the West.

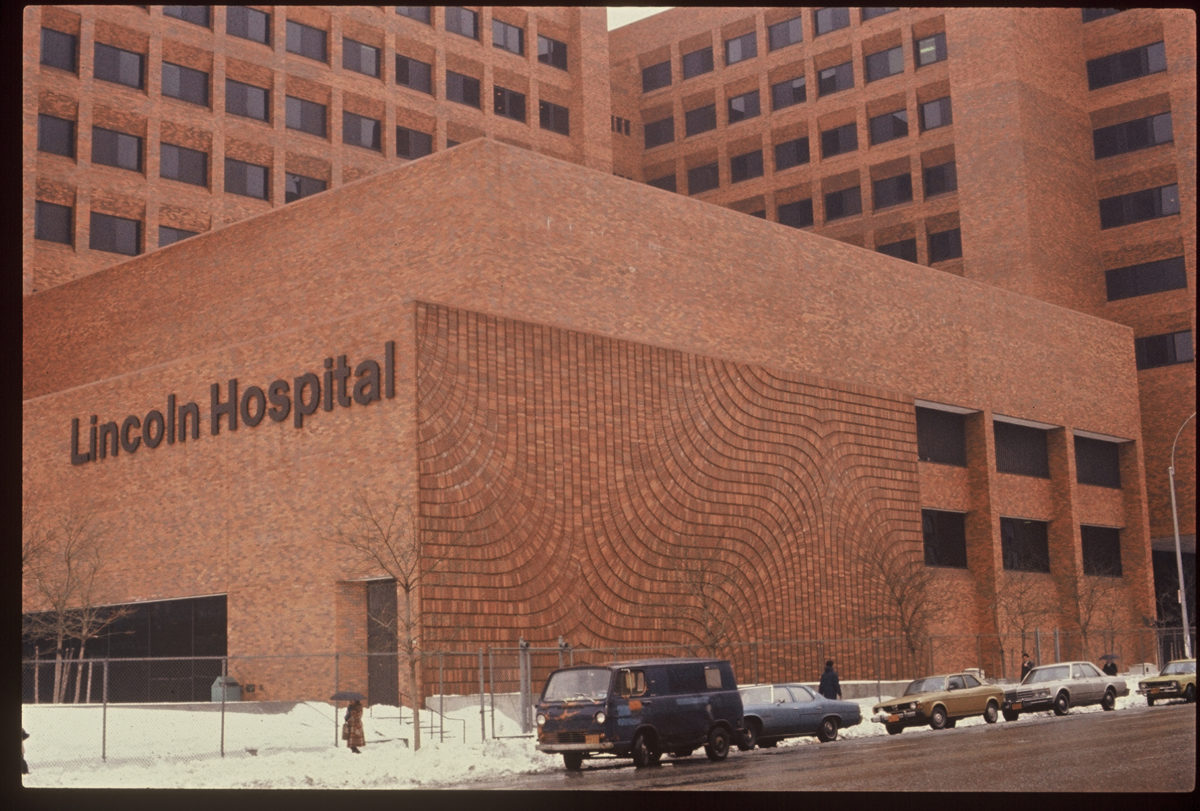

After settling in the United States in 1947, Kasuba entered the American art world by presenting her painted ceramic tiles and mosaics in exhibitions organized within the craft community. This early work led to what constituted the great portion of her artistic activities, namely, monumental decorative commissions for public squares and the interiors and exteriors of buildings across the United States. The undulating lines of her signature brick reliefs—for example, the brick relief she made for the Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx (1973)—invoke movement and suggest an optical activation of a flat surface as her primary concern. Through the late eighties, as she was fulfilling commissions that, among other things, provided a stable means of supporting her family, Kasuba simultaneously engaged in what might be called her studio work. Driven by the desire to reimagine what she regarded as alienating architectural and urban structures, Kasuba created alternative sheltering technologies, disrupting the very architectural order with which she was literally engaged in her decorative work.

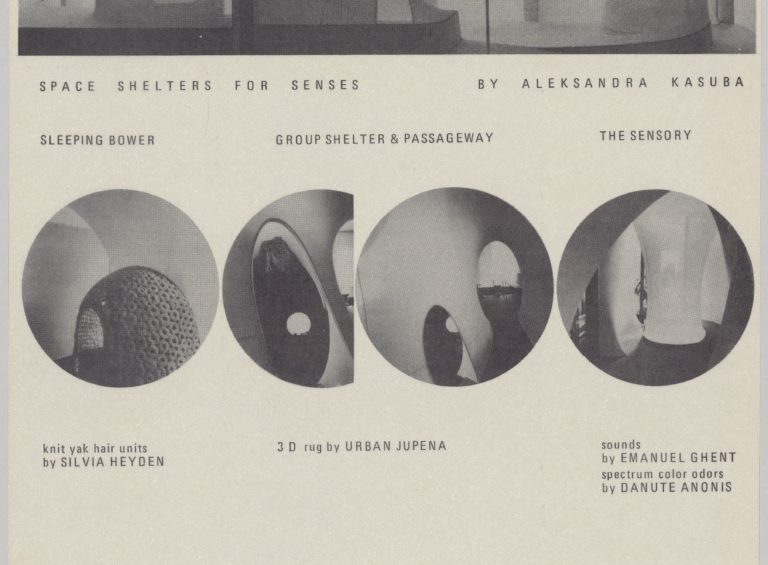

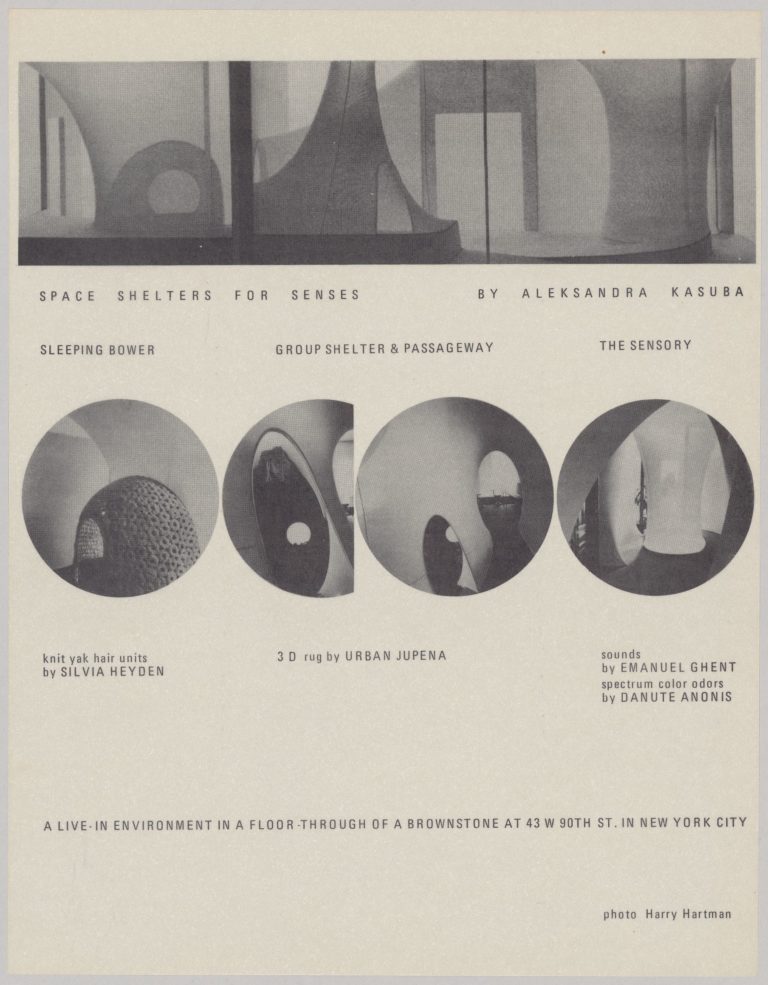

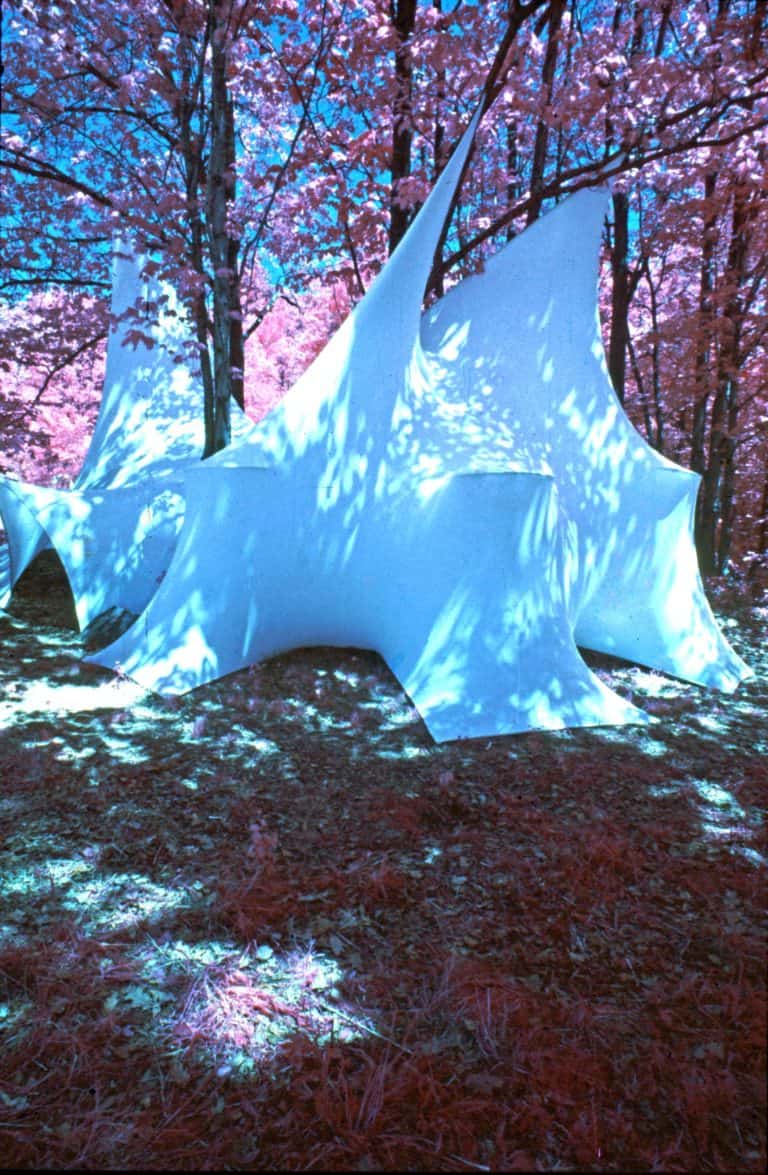

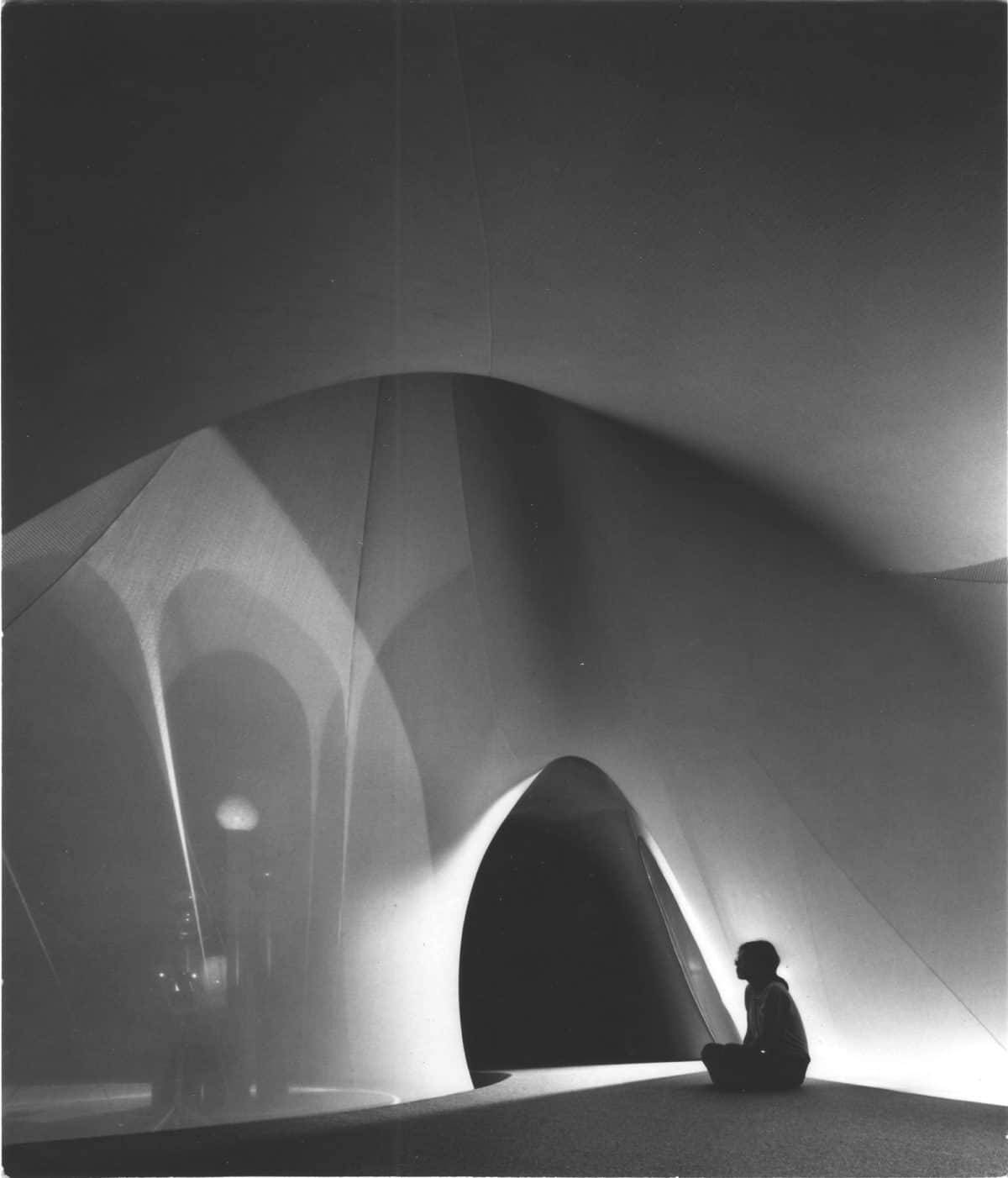

One of the conventions of architecture that the artist aimed to counter in her own space-making practice was the rigid geometry she believed to be oppressive and unnatural to human nature. She questioned whether “the undoing of the rectangle—a fixture so familiar that we no longer question its presence—[would] undo something essential”2Artist’s description of the Live-in Environment, Aleksandra Kasuba papers, c. 1960–2019, bulk 1960–2010. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. via her breakthrough project Live-in Environment (also known as Space Shelters for Senses), which she erected in her family’s brownstone in Upper Manhattan in 1971. Occupying a whole floor, this structure consisted of several interconnected bulbous compartments shaped by stretched milk-white synthetic fabric attached to the ceiling and ground. This cloth, which was originally designed for thermal garments, became her primary medium in conceiving unconventional built environments. Its tensile properties allowed her to sculpturally mold space directly and to defy such architectural staples as a preconceived plan and ninety-degree corners in favor of context-responsive, easily demountable, organically shaped structures formed by hand in situ. Not only did the artist do away with right angles, impenetrable walls, and flat planes in her environment in favor of curves and translucency, she also incorporated additional stimulants, such as lights, mirrors, odors, textures, and sounds, to further alter how the space was perceived and navigated. The altered environment demonstrated her desire to variously enhance the sensations affecting the physical and mental states of its occupants.3The artist described her take on the environment as follows: “I feel an environment is more or less a physical place outside of you which generates certain energies. So now the energies are generated by the objects within it. Therefore some environments are stronger, some are less strong, some impose behaviors, some impose moods, some impose themselves upon the individual so you either don’t want to be in it or you are drawn to it because you respond to it then—to the energies present in it, to that particular circumstantial situation.” Aleksandra Kasuba, interview by Jerilyn Berland, 1976. Aleksandra Kasuba papers, c. 1900–2019, bulk 1960–2010. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Determined to go against the grain of established architectural conventions, she found inspiration and references in multiple areas, from preindustrial architecture, art, and technology programs (in which she aspired to partake4In 1968, Kasuba took part in the exhibition Some More Beginnings: Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) at the Brooklyn Museum,and in 1971, two of her project proposals were included in Maurice Tuchman, A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971 (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1971), 144–45.) to the countercultural ethos advancing the spatial practices and alternative social formations of the time.5In the summer of 1972, Kasuba took part in Whiz Bang Quick City 2, a pop-up city erected in Woodstock, New York. The countercultural event celebrated DIY, cooperation, and alternative community formation. Together with fourteen of her students from the School of Visual Arts, where she briefly taught, Kasuba erected an improvised shelter, forming it in situ by fixing a large piece of tensile fabric to the surrounding trees. On Whiz Bang Quick City 2, see Felicity D. Scott, “Global Village Media: Coming Together in the Early 1970s at Whiz Bang Quick City,” Architectural Design 85, no. 3 (May 1, 2015): 78–85.

Following this prototype installation, which served as the artist’s living space, Kasuba implemented tensile fabric structures in various other spaces, including educational facilities, offices, and exhibition architectures. Some of this work received critical attention—as was the case with The 20th Century Environment (1973), a display for ceramics that was commissioned by the Carborundum Museum of Ceramics in Niagara Falls, New York. Documentation of this structure, which the artist made by arranging the fabric into a soft, curvilinear sculptural enclosure, was later featured in the exhibition Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective at the Brooklyn Museum in 1977, and in Arthur Drexler’s photographic exhibition Transformations in Modern Architecture at MoMA in 1979.

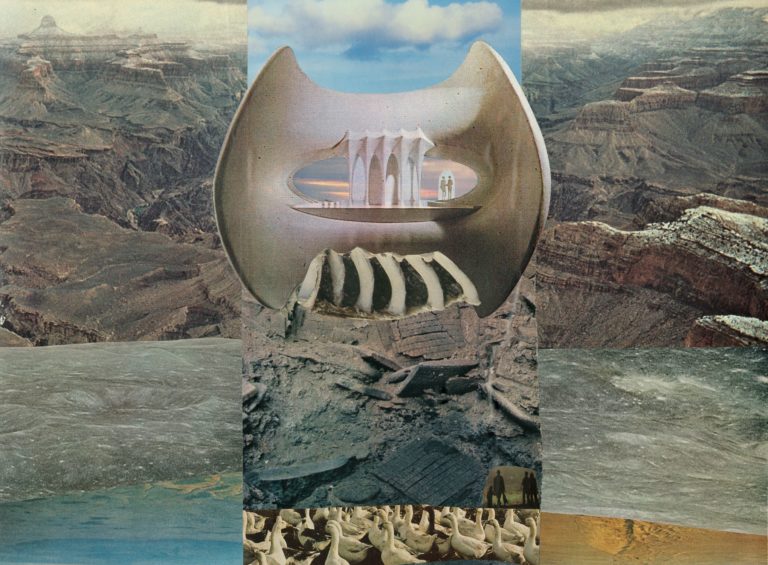

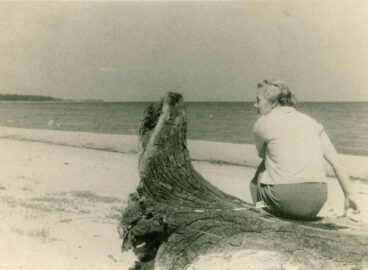

Many of Kasuba’s other projects, such as the stand-alone buildings and habitats that make up a great portion of her legacy, never saw the light of day—beyond drawings, scale models, and collages. One exception is her own house (and two adjacent buildings that served as guesthouses for friends and fellow artists), which she completed in the desert in New Mexico between 2002 and 2005. These constructions manifest the natural world as a source and inspiration of the artist’s formal vocabulary—invoking flower pods, shells, and underwater creatures—and attest to her strong interest in alternative social structures and ways of living.

While preparing for an exhibition in Philadelphia at the Esther M. Klein Gallery at the University City Science Center in 1989, where she had been granted a residency enabling further study of the tensile properties of fabric, Kasuba summed up her visionary explorations: “I am not assessing the results of my work—the world is overloaded with unnecessary things as it is, and I don’t want to increase that pile. Yet the pattern of the development of processes remains sound and strong—I hope . . . I chanced upon some discoveries—or perhaps even transcended certain limits—which, certainly, looks surprising to me too.”6Aleksandra Kasuba to Algirdas Julius Greimas, February 11, 1989, in Algirdo Juliaus Greimo ir Aleksandros Kašubienės laiškai, 52–53. Indeed, what is evident here is that, throughout the years of her experimentations in multiple forms, materials, and scales, the artist sought to understand how the physical environment might contribute to the well-being of its inhabitants.

But also, importantly, through her work, the very fact that the environment is not a neutral container becomes palpable. In an unpublished interview in 1976, the artist recounted her life after dismantling the Live-in Environment, which she had inhabited for more than a year: “I lived in it all that time. I enjoyed it very much. It did not change me. But actually I realized much more fully what it did to me after it was gone. I had to change my hairdo. I didn’t know how to sit. I didn’t know how to talk. I suddenly was completely restricted. And actually I did move out of that place to work somewhere else. But it was quite an experience.”7Kasuba, interview by Berland. As experienced by the artist herself, physical space appears here as an apparatus always actively operating on human bodies and psyches. Not unlike the alternative dwellings of the counterculture of the sixties and seventies, which, as Felicity D. Scott asserts, appeared in their own time as scissions within the system, Kasuba’s experimentations, despite largely remaining in the margins of architectural narrative, might appear as exactly such a case of rendering the techniques of power visible, and opening up horizons for building as an act of refusal.8Felicity D. Scott, Outlaw Territories: Environments of Insecurity/Architectures of Counterinsurgency (New York: Zone Books, 2016). See also Felicity D. Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics after Modernism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).

- 1Kasuba resumed an intellectual dialogue with Algirdas Julius Greimas late in her life. Correspondence between Greimas and Kasuba is published in Algirdo Juliaus Greimo ir Aleksandros Kašubienės Laiškai, 1988–1992 (Vilnius: Baltų lankų leidyba, 2008).

- 2Artist’s description of the Live-in Environment, Aleksandra Kasuba papers, c. 1960–2019, bulk 1960–2010. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

- 3The artist described her take on the environment as follows: “I feel an environment is more or less a physical place outside of you which generates certain energies. So now the energies are generated by the objects within it. Therefore some environments are stronger, some are less strong, some impose behaviors, some impose moods, some impose themselves upon the individual so you either don’t want to be in it or you are drawn to it because you respond to it then—to the energies present in it, to that particular circumstantial situation.” Aleksandra Kasuba, interview by Jerilyn Berland, 1976. Aleksandra Kasuba papers, c. 1900–2019, bulk 1960–2010. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

- 4In 1968, Kasuba took part in the exhibition Some More Beginnings: Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) at the Brooklyn Museum,and in 1971, two of her project proposals were included in Maurice Tuchman, A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967–1971 (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1971), 144–45.

- 5In the summer of 1972, Kasuba took part in Whiz Bang Quick City 2, a pop-up city erected in Woodstock, New York. The countercultural event celebrated DIY, cooperation, and alternative community formation. Together with fourteen of her students from the School of Visual Arts, where she briefly taught, Kasuba erected an improvised shelter, forming it in situ by fixing a large piece of tensile fabric to the surrounding trees. On Whiz Bang Quick City 2, see Felicity D. Scott, “Global Village Media: Coming Together in the Early 1970s at Whiz Bang Quick City,” Architectural Design 85, no. 3 (May 1, 2015): 78–85.

- 6Aleksandra Kasuba to Algirdas Julius Greimas, February 11, 1989, in Algirdo Juliaus Greimo ir Aleksandros Kašubienės laiškai, 52–53.

- 7Kasuba, interview by Berland.

- 8Felicity D. Scott, Outlaw Territories: Environments of Insecurity/Architectures of Counterinsurgency (New York: Zone Books, 2016). See also Felicity D. Scott, Architecture or Techno-Utopia: Politics after Modernism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).