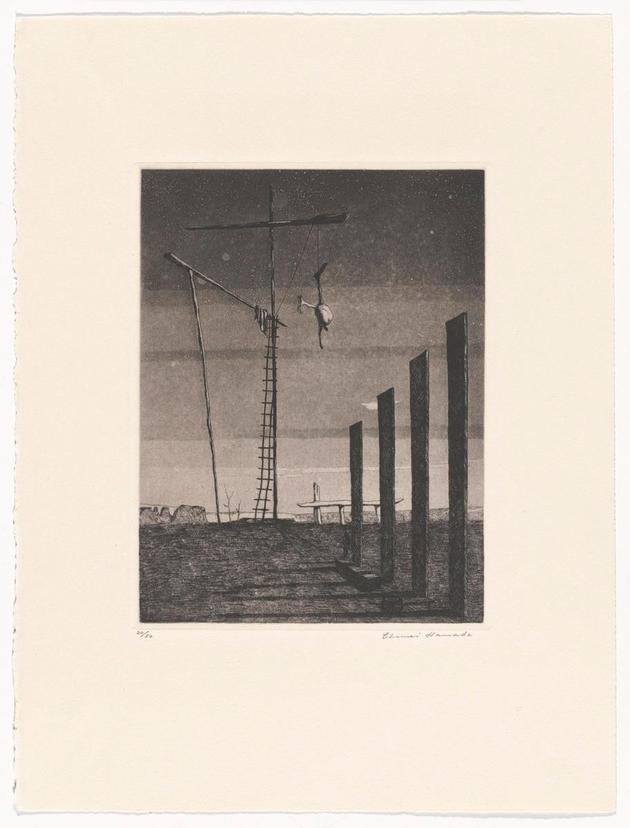

On one of my first trips to Japan in 2008, I visited the Hyogo Prefectural Museum, which has a stellar collection of Gutai work housed in a big Tadao Ando building. Its collection galleries are dominated by painting and sculpture, but hidden among these was a tremendously powerful small etching – a dark scene, surreal and melancholy – by Chimei Hamada, now 96 years old. Widely considered one of the most important artists of his generation in Japan, he is represented in many public collections there, but only rarely in international ones. In subsequent trips over the last several years, I’ve seen and considered, and compared as many impressions of Hamada’s etchings as I could, and that research culminated in the acquisition of a group of five works for MoMA’s collection in 2012.

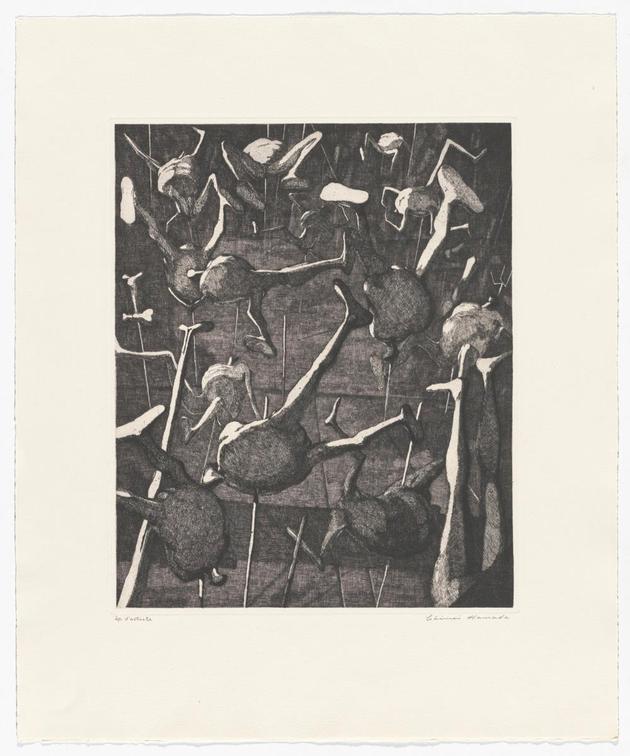

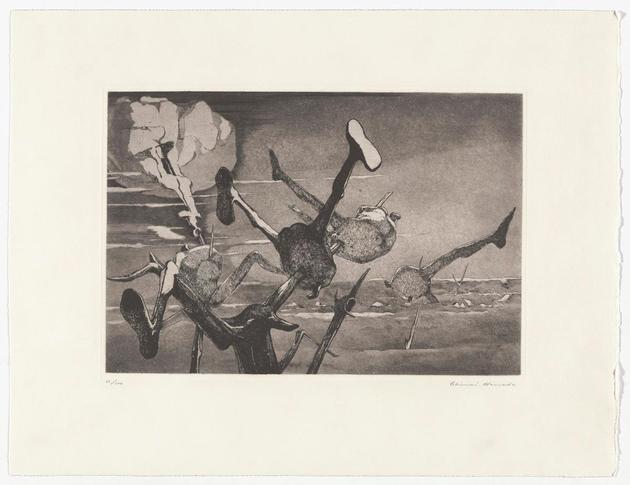

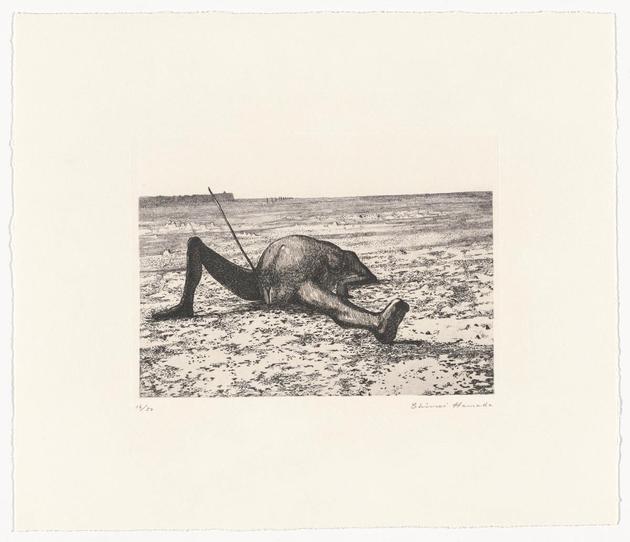

Born in 1919, Hamada studied oil painting at Tokyo Fine Arts School. Upon graduating in 1939, he was immediately drafted into the army and was sent to combat in China. There, he saw firsthand the horrors of the battlefield, the mindless hierarchy of the military, the irrationality of wartime decision-making, the humiliation of powerlessness and inability to think freely. Despondent, but sustained by his artist’s eye, he recorded what he saw, often sketching on tissues as other materials were scarce.

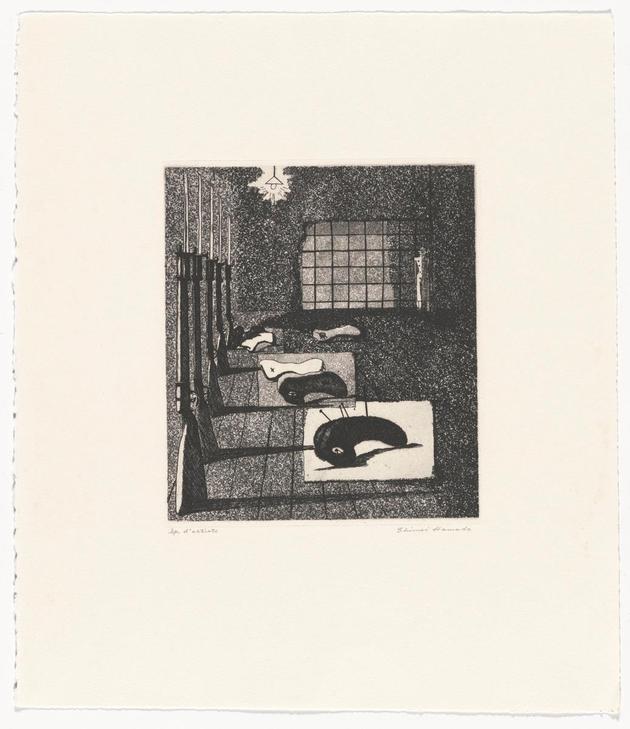

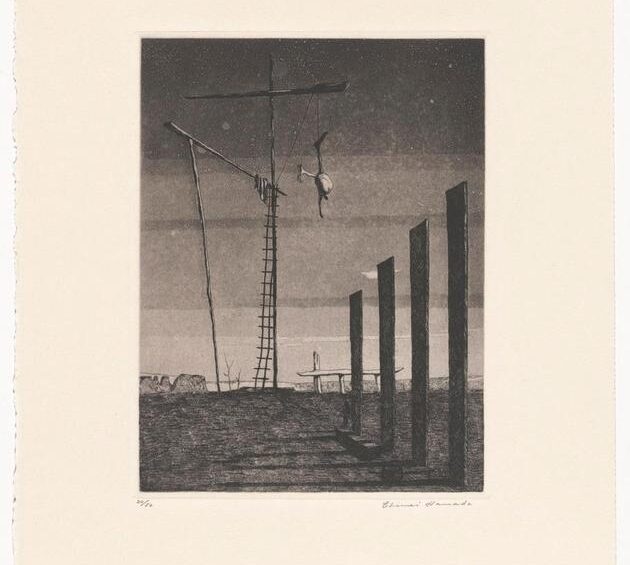

After the war, he settled in Tokyo, and began to process what he had seen during his service, which took the form of small, monochrome etchings of great intensity. The decision to work in this medium was a purposeful one. He describes its metallic sharpness, its cold expression – the way an image emerges from the darkened plate like smoke clearing on the battlefield. He had taken a printmaking class in college, but now devoted himself to the medium, teaching himself aquatint and mezzotint, searching for scarce materials, and even designing and fabricating his own printing press at a machine factory in Nagano.

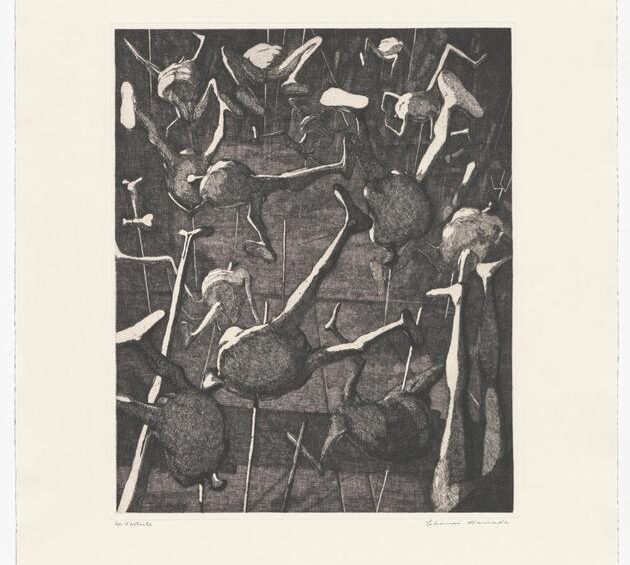

The result was a group of 35 works made during an intense period of creativity between 1950 and 1954, which mark his most compelling artistic achievement, including the five prints that are now in MoMA’s Collection. These are all scenes that depict the tragedy and absurdity of war, but without national, temporal, or geographic identifier, and with an artist’s eye for composition and abstraction of horror. In Under the Shadow, Hamada depicts himself and his fellow conscripts as what he calls caterpillars, regarded by their superiors as no more than insects. The barren landscape of northern China’s Shanxi Province can be seen in several of the plates – a geography that he found both alien and beautiful. The influence of historical precedents and influences is clear. Hamada described what he saw as “The darkness of the Middle Ages transported into the present” presaged in the cruel, anatomical nightmares of Heironymous Bosch, and the war-focused print cycles of Goya and Otto Dix, both of which are already represented in MoMA’s Collection. This selection of works by Hamada offers a fascinating counterpoint to those projects, and a different cultural perspective on an enduring theme.