Around the “Places of Consignation”: The Archive and Yokoo Tadanori

1. Posters and Events

“Dear Kara Juro, please forgive me for being late with this design.” —Yokoo Tadanori (1967)

“It has, in appearance, primarily to do with a private inscription. This is the title of a first problem concerning the question of its belonging to an archive: which archive?” —Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression” (1995)

The poster for the Jokyo Gekijo’s (Situation Theater) 9th Apology Event (Kara Juro’s John Silver—Shinjuku Longing and Crying in the Night Edition; former Sogetsu Hall, May 22–25, 1967) is inscribed with a written apology in the lower right corner of the picture plane—a private message—from the designer to the client. Yokoo Tadanori later described the work as “deviating completely from the function of a poster in that it was completed on the morning of the day of the performance.”1Yokoo Tadanori, “Sakka to boku to design to” (The artist, me, and design), Tokyo Shimbun, Nov. 10, 1978. Quotations by Yokoo cited in the present text are from the following: Senda Akihito, “Yokoo Tadanori to poster no atsui jidai” (The passionate age of Yokoo Tadanori and Posters) in Takahashi Naohiro, Tsukada Miki, Okamoto Hiroki, Dehara Hitoshi, eds., Tadanori Yokoo Be Adventurous! (Tokyo: Kokusho Kankokai, 2008), pp. 82–83. The picture is surrounded by a black border, and its center is also framed by images of countless life-size hanafuda playing cards, each of which is similarly bordered in black.2Hanafuda are traditional Japanese playing cards dating to the Ando-Momoyama era (1573–1603). Initially a two-person game for the elite, the cards are often decorated elaborately, with twelve suites (each with a flower that corresponds to a month of the year) and four cards in each suite. [Editor’s note] Some of the cards—such as the pair of paulownia flower cards at the top and bottom centers—also include inscriptions, apparently copied from existing logos: “‘Fuku’ trademark, all rights reserved,” “Nintendo,” and “Specially manufactured papier maché”). A white moon rising in the background emits light, and there is a dark gray silhouette of a naked woman with her head drooping under the weight of a Shimada-style coiffure. This B1-format (39 3/8″ x 27 7/8″) poster conceived by Yokoo was at that time exceptionally large for an announcement of a performance by a small theater company. Regardless of when it was submitted and displayed in relation to the four-day performance, it did not, as previously noted, arrive in time for the occasion or event. Yokoo has no shortage of similar anecdotes.

Examining the discursive space that is woven from countless historical descriptions of the artist by scholars and curators, we find an outpouring of unstinting praise. After recounting anecdotes about his genius, the majority of the descriptions turn to praising and commending him. Many of Yokoo’s contemporaries weave in personal stories about him, and after praising and commending him, they recount anew the ways in which others have commended him. This discursive space of theories about Yokoo is analogous to the nested aspect of the pictures in his posters.

Yokoo mentions his work’s “deviation” from the “function of the poster” in the above example (the place where his apology is printed). First, let us establish a point here in this text from which to examine the “place of consignation” (that is, the place of exposed private inscription). It would be desirable for the observation point known as an “archive” to simultaneously allow us to survey the place of consignation and the area “outside” of it (even if it is not possible to look at the delicate grain of the silkscreened poster from this point).3Throughout the essay, the author uses the word “grain” in its multiple meanings to refer to the coarseness of the texture of paper, as well as the parallel lines in a cut of wood. The “archival grain” is a term that Ann Stoler elaborates on in her 2009 book Along the Archival Grain. Sen Uesaki’s use of the term is also in conversation with the use the “grain” in writings by Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes, and Millie Taylor, among others. [Editor’s note] “Yet, when it comes right down to it, it doesn’t make much difference to the viewer whether these are posters or not.”4Sawaragi Noi, “Nigiyaka de kurai basho” (A lively, dark place) in Yokoo Tadanori, Recent Works of Poster Art by Yokoo Tadanori (Tokyo: Jitsugyo no Nihonsha, Ltd, 2000), pp. 4–7. This may indeed be true. But Yokoo’s posters are greatly admired in part because they are thought not to fulfill the poster’s fundamental function and original purpose, nor to relate to such criteria. By entrusting our ideas to this view, which anyone might easily subscribe to, we necessarily neglect to address questions related to the poster medium on which Yokoo’s status as a genius rests. When a poster is seen to depart from the fundamental function and original purpose of its medium, it is invariably regarded as the object it used to be in its pre-printed state. But once a poster is a poster, that is to say printed matter, it is impossible for it to deviate from its “function.” The “advantage” of ignoring the fact that these works by Yokoo are posters that announced specific events in the past and yet are still posters (they carry an announcement) is not evident from our archival observation point. The sense of vivacity in Yokoo’s posters (akin to the lucky rakes lined up in the street stalls at the Torinoichi Festival) and what Mishima Yukio identified as their “unbearable darkness cloaked in bright colors”5Mishima Yukio, “Bureina geijutsu” (Rude art) in Yokoo Tadanori no isakushu (Posthumous works of Yokoo Tadanori), ed. Awazu Kiyoshi (Tokyo: Gakugei Shorin, 1968).; the phony threshold that unjustly separates the expressions of a designer and those of an artist; and Kamekura Yusaku’s reason for calling Yokoo “a genius in his own mold,” are all parts of the question of the poster as a form of printed matter.6Kamekura Yusaku quoted in Marta Sylvestrova, “Jidai no nami o tayutau mono” (People who made waves in an era), YokooTadanori, Recent Works of Poster Art, pp. 10–19. “Hatenko no tensai. Soko ga omoshiroi. (Jishin no igata no naka no tensai)” (Unprecedented genius: that’s interesting—a genius in his own mold.) Originally quoted in Yokoo Tadanori (Tokyo: Ginza Graphic Gallery, ggg Books 28, 1997), pp. 4–7. So what exactly is a poster?

Every page of bulky catalogues like Yokoo Tadanori Gurafikku Daizenshu (The complete Tadanori Yokoo graphic works, Kodansha, 1989), Yokoo Tadanori no zen posta (Yokoo Tadanori’s complete posters, Seibundo Shinkosha, 1995), and Yokoo Tadanori zen posta (The Complete Posters of Yokoo Tadanori, Kokushokankokai, 2010), which announce their comprehensiveness with the word “complete” (zen) in their original Japanese titles, plays a part in enumerating the artist’s work. The covers of many of these books were created by Yokoo himself, and the catalogues also often assume a nested form. They provide a chronological listing of Yokoo’s work, and images of his posters are printed on the surface of each page. The posters are reduced to function as the content (plate) on each page, and after being laid out (planned, prepared, arranged, and placed) are embedded as separate entities in the surface of a distinct skin. The paper of the book is a new and uniform skin that by implication mimics the printed grain of the posters, but relies on the use of offset printing, characterized by the absence of direct contact between the skin of the printing plate and the skin of the paper. Moreover, the places that are not occupied by the (images of the) posters—that is, the blank spaces that are visible in the margins on every page of the catalogue—function as the “outside” of the (image of the) poster. It is also here that we find a description explaining each poster. Notes on the printing technique, such as “silkscreen on paper” or “offset on paper,” and the dimensions typically accompany such entries. This blank space that remains on each page is neither part of the actual assemblage of content on the page nor the subject of interest. Yet, despite its position on the perimeter or outside, it shares the same continuous skin as the content. Naturally, the blank space remains as it is. The perimeter of the plate of the small, reprinted poster is not cut off. From our [archival] observation point in this text, the blank space is the second “place of consignation.” And it is the grain of this blank space, which has passed through the printing press several times along with the content on the page, that is the grain of the archive.

This blank space, this outside, could be explained by the joy that André Malraux emanated when he spread his study floor full of his catch (in this case, the photographic prints). The photographs, which are the subject of the Malraux photograph, are supported from beneath by the photographs themselves.7In the famous photograph of Malraux by Maurice Jarnoux, the French author and critic stands gazing over a sea of photographs spread across his study floor in the process of choosing photographs for the book Le Musée imaginaire. [Editor’s note] In the process of preparing the artwork for Kara Juro’s John Silver, Yokoo “said he took some real hanafuda cards, made the text, and affixed them to a piece of plywood, and carried it to the print shop.”8Hirano Koga and Oyobe Katsuhiko, “Dialogue: Underground Graphics,” in Gendai engeki no art work 60’s–80’s: Poster / Butai bijutsu ni mire shogekijo undo no kiseki (Art work of contemporary theatre 60’s-80’s: the trajectory of the little theatre movement as seen in posters and stage design) (Tokyo: Seibu Bijutsukan, 1988). The comment is Oyobe’s. Not only did Yokoo deal with the hanafuda cards as printed matter, he took the actual cards to be printed. After understanding this, we once again return to the question of what constitutes a poster.

To come right to the point, a poster is a sign—it serves as a harbinger and conveys a promise. In the present, according to the grain of the archive, the poster recalls the occasion or event that it announced many years ago (and continues to announce today). But the fact is that as this piece of printed matter announced an anticipated event, we must not forget that every poster is printed prior to the occasion that is its subject. As a herald of the event, it most closely resembles a witness in the archive, but without ever touching on what actually happened. It merely testifies to what was proposed; some posters announce events that were canceled, but obviously this does not mean that they give false testimony. The witnesses are verbose, and they still continue to reminisce about the immediate future without knowing anything about how the events of the past that they anticipated actually transpired. Such witnesses, as preliminary announcements or messengers, probably have a more direct connection to the overall event than other witnesses, such as documentary photographs or audio or video recordings that have captured the outcomes of the event. This is due not only to the fact that the reality of a past event lies in the amplitude between the proposed and the actual, but also to the fact that, insofar as it recollects the future and predicts the past, a poster has a dual purpose. “When Yokoo arrived on the scene, everybody became very upset. They said things like it was meaningless [to make a poster] unless you used B-zen size [728mm × 1,030mm] paper… During that period, it was completely viable for a poster to influence the play. For example, they changed the play that they did after John Silver due to the impact of the poster for the previous play.”9Koga’s comment from “Dialogue: Underground Graphics.” The quote comes from Senda Akihito’s “The Passionate Age of Yokoo Tadanori and Posters” (see footnote 1).

2. Spoilage

“The advent is a promise of events.” —Maurice Merleau-Ponty, “Indirect Language and the Voices of Silence ” (1952)

“It conditions not only the form or the structure which prints, but the printed content of the printing: the pressure of the printing, the impression, before the division between the printed and the printer. This archival technique has commanded that which even in the past instituted and constituted whatever there was as anticipation of the future.” —Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (1995)

Derrida writes: “[psychoanalysis] does not privilege by chance the figure of the imprint and the printer.”10Jacques Derrida, “Prière d’insérer” (Please insert). This is an addendum added to the French version of Derrida’s text Mal d’archive (Paris: Éditions Galilee, 1995). “Elle [la psychanalyse] ne privilégie pas par hasard les figures de l’empreinte et de l’imprimerie.” Translation by Sen Uesaki. The archive of printed matter is constantly related to (an assemblage of) subject matter, but there is no room for growth in the subject itself. An archive remains “outside” the subject of interest. By the time we begin to refine the question, dismiss the false division between, for example, the quantity of art versus the quantity of design, and ask “What is a poster?” we have already redrawn several times the line that indicates the point at which the archive begins. In other words, an archive reestablishes its position on the outside each time the observer bores through a multilayered, stratified group of dividing lines. While on the one hand we might say that the grain of the blank spaces on every page of Yokoo’s catalogues has the grain of an “archive,” this is due to the fact that our observation point in this text, which provides a clear view of this kind of grain, can be seen as that of an “archive.” An archive exists outside a concept that indicates itself and refuses all rules except the one that concerns gathering a number of examples as an assemblage (extension) of concrete subjects. The place from which we ultimately survey these examples is necessarily outside. If we were to create a new observation point (a change of air) by taking one step back, obtaining a new view that includes the one we are afforded from the observation point in this text, that place would, in other words, be called an “archive.” The process of archivization is always conducted from a specific observation point with regard to the (assemblage of) content, but gradually this observation point is objectified as a kind of vessel. Thus, the archive becomes multilayered: /archive/archive/////…

According to one chronology, after graduating from Nishiwaki High School (Hyogo Prefecture) in his hometown in 1955, Yokoo planned to enter the oil painting department at Musashino Art University and moved to Tokyo to take the entrance exam, but out of concern for his “aged parents,” he abandoned the idea and returned to Nishiwaki. A few months later, his poster for the local Textile Festival (May 7 and 8, 1955) was selected, leading him to take a job at a printing company in Kakogawa (he quit six months later). Apparently, the thing that he found most interesting about the printing process was the spoilage (torn paper).11For information on Yokoo’s interest in spoilage, I referred to an explanation in Tadanori Yokoo: All Things in the Universe by Midori Wakakuwa, Yusuke Minami, Hitoshi Dehara (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 2002), p. 61.

In the printing cycle, in processes such as trail printing, some of the paper is inevitably damaged and removed from the printed matter that is set to be delivered to the client. The damaged paper, which has been run through the press several times, is called “spoilage,” and it is accumulated and recycled. This process of printing on waste paper to adjust a new plate and the press itself, and the use of spoilage in the process, is nothing less than the “/” [slash] that is introduced to establish a division between that which is printed and that which prints. The reuse of torn paper as printed matter stems not only from economic reasons. In order to prepare the printed matter to be printed, it is necessary to integrate that which prints into that which is printed in order to achieve the desired grain of the printed matter. Each time the paper passes through the press, an unexpected overprint occurs on the surface of the paper which is unrelated to the layers of print that are a regular part of the printing process.

The complicated tangle that appears on the surface of the spoilage is by no means predetermined. I am not attempting to superimpose an excessive layering of multiple grains that belong to (or are lost in) a multitude of different wholes on the surface of the spoilage, which captured Yokoo’s interest, to arrive at the artist’s specific approach to printed matter. Spoilage cannot be the third “place of consignation” in this text. The complications on the surface of the spoilage have a decidedly different character from a planned overlapping of plates. The multiple layers of grain on the spoilage are overwhelming but at the same time lack both body and coverage. After repeatedly passing through the press, the paper is dedifferentiated. The spoilage leads us to the complicated tangle of discursive space arising out of the critical praise and commendation that turns out to be devoid of an archive (en mal d’archive, in Derrida’s terms). However, from an archival perspective, we do not select (do not establish the outside) a particular picture from Yokoo’s work.

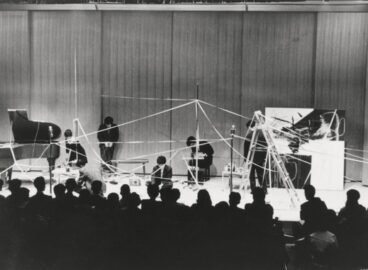

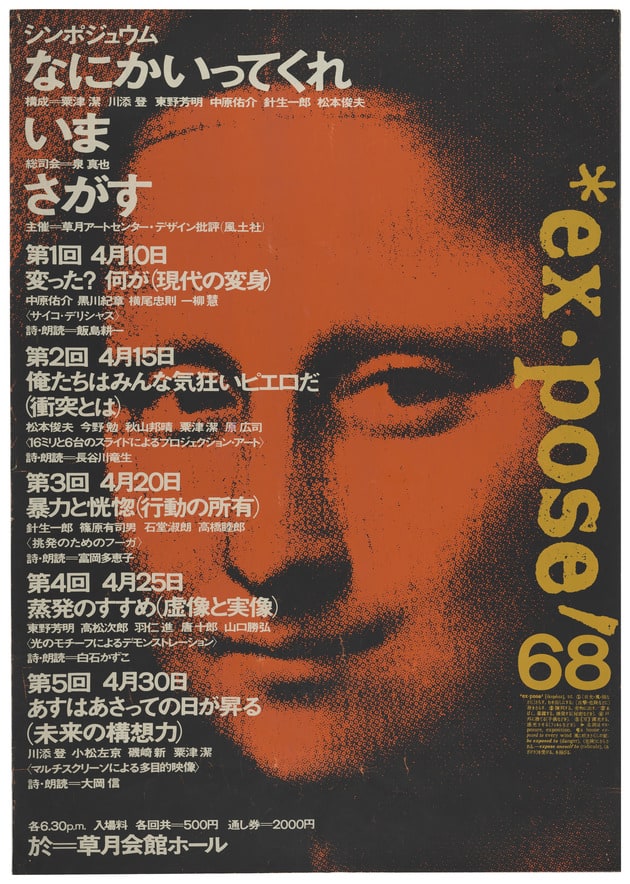

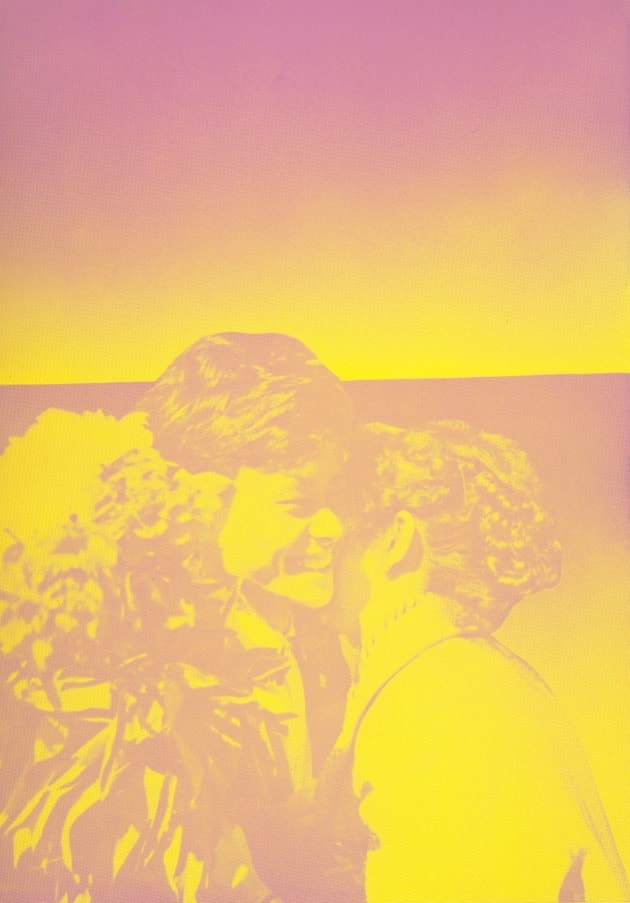

Finally, I would like to turn to some specific posters at a specific event. “Changed? What? (Contemporary Transformation)” (held at the former Sogetsu Art Center Hall, April 10, 1968) was the first part of a multiday symposium called “Expose 1968: Nanika Ittekure, Ima Sagasu” (Expose 1968: Say something, I’m trying), which was co-organized by the Sogetsu Art Center and Design Review (Fudosha). The introduction, “Psycho Delicious,” was overseen by three people: Ichiyanagi Toshi, Kurokawa Noriaki [Kisho], and Yokoo. Apparently, it ended without ever beginning, in keeping with the artists’ idea that “because we don’t believe in words, we won’t make any statements.”12Izumi’s Shinya’s explanation appeared in Design Review, no. 6, July 1968, p. 19. Posters with photographic portraits of the composer, architect, and graphic designer were hung at the rear of the stage (horizon) without any gaps between them.

Yet, these witnesses that we have called forward into the here and now cannot provide us with any evidence of the event that they created together. In this specific place of consignation, there is no recorded information, neither a public notice of content nor a personal note.13The names Toshi Ichiyanagi, Noriaki Kurokawa, and Tadanori Yokoo are apparently inscribed in the border at the bottom of the posters, but in the small-scale reproduction that appears in the catalogue, it is difficult to decipher them among the halftone dots. These witnesses that were linked in a performative relationship to the event that they themselves anticipated remain completely silent about every aspect of that event, including themselves, the posters. Indeed, the performative witnesses repeat themselves as subjects in documentary photographs of the event and imitate (perform an “archive” in the photograph) the nesting aspect of these documentary photographs depicting the posters. This is the mold for Yokoo’s posters, which ceaselessly create the multiple layers of the archive. Derrida might offer the following explanation in regard to this type of example related to printed matter: “Because the archive, if this word or this figure can be stabilized so as to take signification, will never be either memory or anamnesis as spontaneous, alive and internal experience. On the contrary: the archive takes place at the place of originary and structural breakdown of the said memory. There is no archive without a place of consignation, without a technique of repetition, and without a certain exteriority. No archive without outside.”14Derrida, p. 14.

To “Say something.” Is this unwritten title the thing that is inscribed “outside” the assemblage of the posters? If the poster is waiting for a title other than the name of the event that it anticipates, where was the place that the title was inscribed at that time? Wasn’t the title given according to the grain of the blank space after the dividing line was drawn to indicate the beginning of the archive? Say something, I’m trying. In the end, whose voice is responding to the line (both a call and a reply) that Awazu Kiyoshi borrowed from Waiting for Godot?

Note: The Japanese version of this text is adapted from an essay that appeared in the November 2012 issue of Eureka 44(13) under the same title.

Text translated into English by Christopher Stephens.

- 1Yokoo Tadanori, “Sakka to boku to design to” (The artist, me, and design), Tokyo Shimbun, Nov. 10, 1978. Quotations by Yokoo cited in the present text are from the following: Senda Akihito, “Yokoo Tadanori to poster no atsui jidai” (The passionate age of Yokoo Tadanori and Posters) in Takahashi Naohiro, Tsukada Miki, Okamoto Hiroki, Dehara Hitoshi, eds., Tadanori Yokoo Be Adventurous! (Tokyo: Kokusho Kankokai, 2008), pp. 82–83.

- 2Hanafuda are traditional Japanese playing cards dating to the Ando-Momoyama era (1573–1603). Initially a two-person game for the elite, the cards are often decorated elaborately, with twelve suites (each with a flower that corresponds to a month of the year) and four cards in each suite. [Editor’s note]

- 3Throughout the essay, the author uses the word “grain” in its multiple meanings to refer to the coarseness of the texture of paper, as well as the parallel lines in a cut of wood. The “archival grain” is a term that Ann Stoler elaborates on in her 2009 book Along the Archival Grain. Sen Uesaki’s use of the term is also in conversation with the use the “grain” in writings by Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes, and Millie Taylor, among others. [Editor’s note]

- 4Sawaragi Noi, “Nigiyaka de kurai basho” (A lively, dark place) in Yokoo Tadanori, Recent Works of Poster Art by Yokoo Tadanori (Tokyo: Jitsugyo no Nihonsha, Ltd, 2000), pp. 4–7.

- 5Mishima Yukio, “Bureina geijutsu” (Rude art) in Yokoo Tadanori no isakushu (Posthumous works of Yokoo Tadanori), ed. Awazu Kiyoshi (Tokyo: Gakugei Shorin, 1968).

- 6Kamekura Yusaku quoted in Marta Sylvestrova, “Jidai no nami o tayutau mono” (People who made waves in an era), YokooTadanori, Recent Works of Poster Art, pp. 10–19. “Hatenko no tensai. Soko ga omoshiroi. (Jishin no igata no naka no tensai)” (Unprecedented genius: that’s interesting—a genius in his own mold.) Originally quoted in Yokoo Tadanori (Tokyo: Ginza Graphic Gallery, ggg Books 28, 1997), pp. 4–7.

- 7In the famous photograph of Malraux by Maurice Jarnoux, the French author and critic stands gazing over a sea of photographs spread across his study floor in the process of choosing photographs for the book Le Musée imaginaire. [Editor’s note]

- 8Hirano Koga and Oyobe Katsuhiko, “Dialogue: Underground Graphics,” in Gendai engeki no art work 60’s–80’s: Poster / Butai bijutsu ni mire shogekijo undo no kiseki (Art work of contemporary theatre 60’s-80’s: the trajectory of the little theatre movement as seen in posters and stage design) (Tokyo: Seibu Bijutsukan, 1988). The comment is Oyobe’s.

- 9Koga’s comment from “Dialogue: Underground Graphics.” The quote comes from Senda Akihito’s “The Passionate Age of Yokoo Tadanori and Posters” (see footnote 1).

- 10Jacques Derrida, “Prière d’insérer” (Please insert). This is an addendum added to the French version of Derrida’s text Mal d’archive (Paris: Éditions Galilee, 1995). “Elle [la psychanalyse] ne privilégie pas par hasard les figures de l’empreinte et de l’imprimerie.” Translation by Sen Uesaki.

- 11For information on Yokoo’s interest in spoilage, I referred to an explanation in Tadanori Yokoo: All Things in the Universe by Midori Wakakuwa, Yusuke Minami, Hitoshi Dehara (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 2002), p. 61.

- 12Izumi’s Shinya’s explanation appeared in Design Review, no. 6, July 1968, p. 19.

- 13The names Toshi Ichiyanagi, Noriaki Kurokawa, and Tadanori Yokoo are apparently inscribed in the border at the bottom of the posters, but in the small-scale reproduction that appears in the catalogue, it is difficult to decipher them among the halftone dots.

- 14Derrida, p. 14.