In times of danger, we learn to seek sanctuary—a place of safety and security when the world we know is under attack. Once we have regained our strength, perspective, and a better vantage point for reclaiming what was lost, we must consider when to leave the protective space that has sheltered us from harm. During the 20th century, art museums served as venues for Haitian Vodou–based works. In The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti, historian and anthropologist Kate Ramsey explores how the Haitian government targeted Vodou practitioners, illustrating how Haitian Vodou artists were deemed enemies of the state in practice.1Kate Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti (University of Chicago Press, 2011), 120. However, after the US Occupation (1915–34), the Haitian government used Haitian Vodou art in its pursuit of cultural patrimony. In 2003, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, then president of Haiti, recognized Vodou as one of the country’s official religions.2Carol J. Williams, “Haitians Hail the ‘President of Voodoo,” Los Angeles Times, August 3, 2003, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-aug-03-fg-voodoo3-story.html. Even though Vodou artworks are seen in museums and galleries worldwide, the stigma of danger and mystery associated with the practice of Vodou and the art related to it has not diminished.

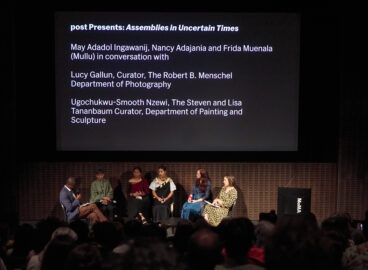

In the fall of 2024, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, hosted Spirit & Strength: Modern Art from Haiti. Curated by Kanitra Fletcher, this exhibition showcased the museum’s first acquisitions of Haitian modern and contemporary art. Featuring 21 paintings gifted by Kay and Roderick Heller and by Beverly and John Fox Sullivan, it offered a diverse range of subject matter encompassing daily life, religious traditions, popular customs, rituals, portraiture, and historical paintings.3Spirit & Strength: Modern Art from Haiti, National Gallery of Art, September 29, 2024–March 9, 2025, https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/spirit-strength-modern-art-haiti. The artist Edouard Duval-Carrié (American, born Haiti, 1954), whose work is included in the collection, delivered the keynote address, titled “Reframing Haitian Art: An Artist’s Point of View,” at the opening reception. He discussed the significant contributions made by Haitian artists to contemporary art. However, he did not fully speak to how Vodou practitioners, whose artworks once adorned the walls of peristils (Vodou temples), have been rebranded and presented only as artistic contributors to the Haitian narrative on display in museums. In this article, I will illustrate the importance of Vodou themes to Haitian cultural expression and examine how, in times of peril, museums in Haiti and the United States may have inadvertently contributed to the ongoing silencing of Vodou.

In the 1940s, US and European art markets as well as museums began pursuing Haitian art, unknowingly creating a “sanctuary” space for Haitian Vodou art, which possesses plural narratives of the sacred and the contemporary.4Lawrence Witchel, “Haitian Primitives: From Art Form to Souvenirs,” New York Times, September 8, 1974, https://www.nytimes.com/1974/09/08/archives/haitian-primitives-from-art-form-to-souvenirs-art.html. Popular indicators of Vodou imagery include ceremonial objects such as the rattle as well as key deities and figures. The ongoing relationship that developed between Vodou artists and foreign cultural institutions also provided a hedge of protection from the persecution that devotees were suffering at the hands of the Haitian government. However, their contributions to contextualizing Vodou visual art has yet to be integrated: The sacred narrative of Vodou is preserved within museum collections but remains silenced in its presentation. In this article, I will unpack the spiritual components of Haitian art and culture.

Vodou is a traditional Afro-Haitian religion blending elements of West African Vodou and Roman Catholicism. From the 16th to 19th century, in the context of the transatlantic slave trade, Spanish and French colonizers transported captured Africans to the New World. Upon arrival, these captives were forced to either become baptized and follow the Roman Catholic faith or face persecution.5Dowoti Désir, “Vodou: A Sacred Multidimensional, Pluralistic Space,” Teaching Theology & Religion 9, no. 2 (2006): 93. During this period, the western side of the island of Saint-Domingue—currently known as Haiti—was governed by the Code Noir, or “Black Code,” a set of laws that regulated the lives of both enslaved and free people of color in the French colonial empire.6Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law,24. To adapt to these demands, enslaved Africans found parallels between Catholic saints and their own African deities.7Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy (Vintage, 1984), 172. Thus, a syncretic religion arose among the descendants of various African nations, including the Dahomean, Kongo, and Yoruba.

During the Haitian Revolution, caves and tunnels served as a network of underground passages connecting enslaved communities across plantations as well as places where Vodou rituals occurred without colonial persecution.8Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law,43. Vodouisants often hid sacred items within busts of Catholic sculptures. Meanwhile, representations associated with the two religions became visually indistinguishable.9Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, 176. However, the 1805 Haitian Constitution recognized freedom of worship, and as the new Republic formed, the postrevolutionary government maintained Vodou as the popular belief system.10Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law, 51. By the 1900s, the partnership between the Catholic Church and the Haitian government influenced members of the new Haitian ruling class, who adopted their former colonial captors’ view of Vodou as a “spiritualized militancy” that challenged the government’s legitimacy and redefined aesthetic tendencies.11John Merrill, “Vodou and Political Reform in Haiti: Some Lessons for the International Community,” Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 20, no. 1 (1996): 42, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45288959.

During the US Occupation, Vodou temples and artifacts were destroyed and confiscated by US soldiers while, at the same time, the Haitian government routinely harassed and arrested Vodou practitioners.12Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law, 51. In 1928, Jean Price-Mars, a medical doctor and anthropologist, wrote the manifesto Ansi parla l’oncle (So Spoke the Uncle), in which he refutes the occupation and supports Haitian cultural nationalism against foreign interests. His speeches and writing inspired Haitian Indigènisme, a movement that embraced the ideology that the promotion of Haiti’s folklore and African heritage was key to its cultural identity and defense against US Occupation.13Jean Price-Mars, So Spoke the Uncle, trans. Magdaline W. Shannon (Three Continents Press, 1983), xi. This proclamation inspired young leftist Haitian scholars to publish La Revue indigène, a literary journal featuring articles, poems, and interviews that sought to offer a perspective on Haitian life and culture that was authentic and integral to Haitian identity.14Michel-Philippe Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt: Haitian Art, 1927–1944,” in “Haitian Literature and Culture, Part 2,” special issue, Callaloo 15, no. 3 (1992): 711, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2932014. Haitian scholars sought to expose colonial devices, to encourage recognition of Haiti as an emerging nation, and to disassociate themselves from the traumatic memories of the previous century.

Indigènist writers such as Philippe Thoby-Marcelin and Émile Roumer urged Haitian artists to create innovative works exploring Surrealism and Expressionism while moving away from European notions of art and beauty. They encouraged artists to focus on Haitian realities such as the local landscape, rural life, and the local flora and fauna.15Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt,” 716. The Indigènist writers did not view Vodou as a means of achieving the recognition of modernity they sought. Having come from affluent families, many had had the opportunity to study in Europe and, therefore, had come to view Vodou as a nostalgic backdrop to their poems and essays. Meanwhile, their audience, composed of the metropolitan bourgeoisie, viewed Vodou as a rural, backward practice maintained by peasants.16Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt,” 716. Within the framework of these movements, there was no space for Haitian Vodou artists to share their subject matter and its layered meanings. Nor was there anywhere for them to reflect on how to navigate their identity in terms of the sacred and the secular.

The Catholic Church and the Haitian government led various anti-Vodou campaigns that resulted in the deaths of many practitioners. In the 1940s, the Roman Catholic Church and the Élie Lescot regime launched an “anti-superstition” campaign that contributed to the secularization of Haitian art. They destroyed the peristils that artists had decorated and maintained as part of their spiritual practice.17Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law, 197. During this tragic period, the Centre d’Art, a government-sponsored nonprofit cultural institution in Port-au-Prince, was established in 1944. Led by the American artist DeWitt Peters (1902–1966), the Centre aimed to promote Haiti’s artistic intellectuals by showcasing that their values were in alignment with the Indigènist movement. Peters, a conscientious objector sent to Haiti to teach English during World War II, was intrigued by the level of Haitian art being produced but not promoted.18Eleanor Ingalls Christensen, The Art of Haiti (Art Alliance Press, 1975), 44. According to the Centre d’Art archives, Peters sought new talent by exploring rural communities.19Christensen, The Art of Haiti, 50. As Vodou-based artists witnessed the destruction of their works in sacred native spaces, and with lives and communities threatened, art museums outside of Haiti began to provide space and agency for Haitian art. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), for instance, became the first mainstream art institution to acknowledge the importance of the Indigènist painting movement in Haiti by acquiring Le combat des coqs (Cock Fight) by René Vincent (Haitian, 1911–?) in 1940.20Marta Dansie and Abigail Lapin Dardashti, “Notes from the Archive: MoMA and the Internationalization of Haitian Painting, 1942–1948,” post: notes on art in a global context, January 3, 2018, https://post.moma.org/notes-from-the-archive-moma-and-the-internationalization-of-haitian-painting-1942-1948/.

An artist associated with the Centre d’Art whose work brought attention to Haitian art forms was the carpenter and blacksmith Murat Brierre (Haitian, 1938–1988). Brierre was introduced to the Centre by fellow Vodou practitioner and artist Rigaud Benoit (Haitian, 1911–1986), who initially came to the Centre as DeWitt Peter’s chauffeur.21Christensen, The Art of Haiti, 51. Brierre learned to create metal sculptures from George Liautaud (Haitian, 1899–1991), the father of Haitian metalwork. Brierre’s sculptures were hand-forged from oil drums discarded from container ships that refueled in Haiti.22Christensen, The Art of Haiti, 52. He developed a highly experimental style, often focusing on multifaceted and interconnected figures. One of his notable sculptures, Metamorphosis, illustrates the transformation of a woman into a bird (fig. 1). The top of this long metal sculpture features a woman’s head, while the base represents the body of a bird in mid-flight. The torso of the sculpture combines elements of both life forms, portraying them as one. While at first glance the work does not appear to be representing spirituality, it in fact depicts “mounting,” a Voudou concept referring to the possession of a devotee by a spirit, or lwa, during a Vodou ceremony. The lwa is believed to take control of the body—rendering it a vessel for movements, voice, and words that are understood to be those of the spirit. “Mounting” symbolizes the Vodou belief that humanity is physically and spiritually connected to all things. Brierre and other Vodouisants, such as Wilson Bigaud (Haitian, 1931–2010) and Hector Hyppolite (Haitian, 1894–1948), found creative sanctuary in their association with the Centre, which enabled them to express their Vodou identities through their artwork.

Unlike the Centre d’Art, Saint-Soleil was a spiritually based rural arts community that focused on tourism to promote Haitian art while attempting to create a “safe space” for the Vodouisant. Established in 1973 by Jean-Claude “Tiga” Garoute (Haitian, 1935–2006) and Maud Robart (Haitian, born 1946), the movement is based on the practice of “rotation artistique”—a technique in which students move freely between art mediums and are encouraged to favor intuition, academicism, and spirit possession in their method of operation.23Merrill, “Vodou and Political Reform in Haiti,” 45. The Haitian principle of kombit (collective creation of works) was central to the many artists and Vodouisants who joined the movement. This groundbreaking experiment empowered mountain-dwelling peasants with no prior exposure to art to explore spirituality and creativity, garnering them international attention.

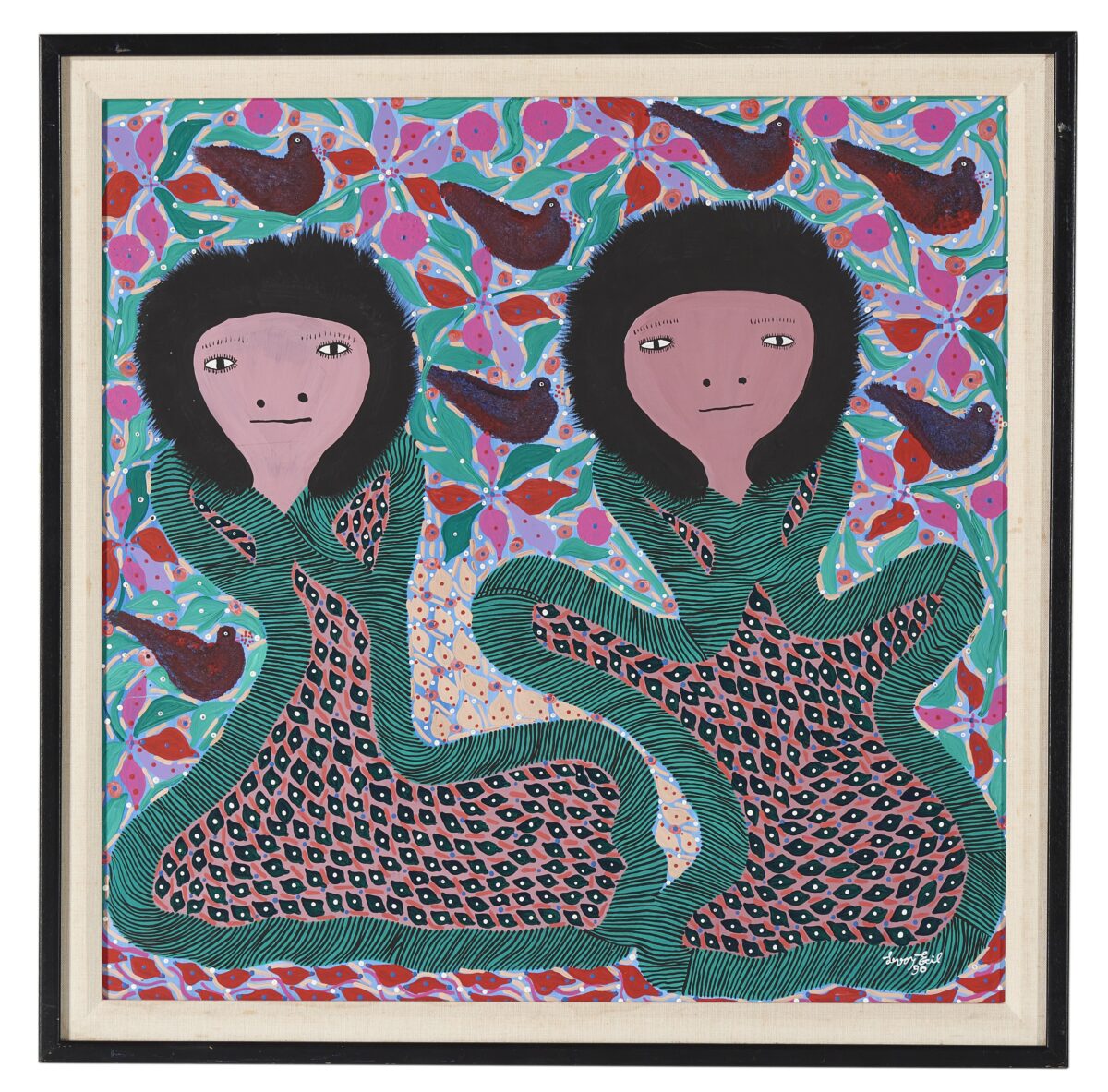

As in other cultural organizations, artists from Saint-Soleil utilized galleries and museums to raise awareness of Haitian art, amplifying the material culture of Vodou. Levoy Exil (Haitian, born 1944) was a prominent artist of the Saint-Soleil movement. In his painting Female Twins (fig. 2), two nearly identical women face the viewer. They are lwa—specifically Marassas, or the divine twins. Their bodies resemble vines and snakeskin and are not confined by a traditional physical form—indeed, they are flexible rather than rigid.

However, by the late 1980s, the Duvalier dictatorship had come to an end, and due to political unrest, foreign travel to Haiti became difficult.24Mambo Chita Tann, Haitian Vodou: An Introduction to Haiti’s Indigenous Spiritual Tradition (Llewellyn, 2012), 43. This caused interest in the Haitian art market to decline, and Saint-Soleil could no longer sustain its artists, leading global enthusiasm for Haitian art to wane.

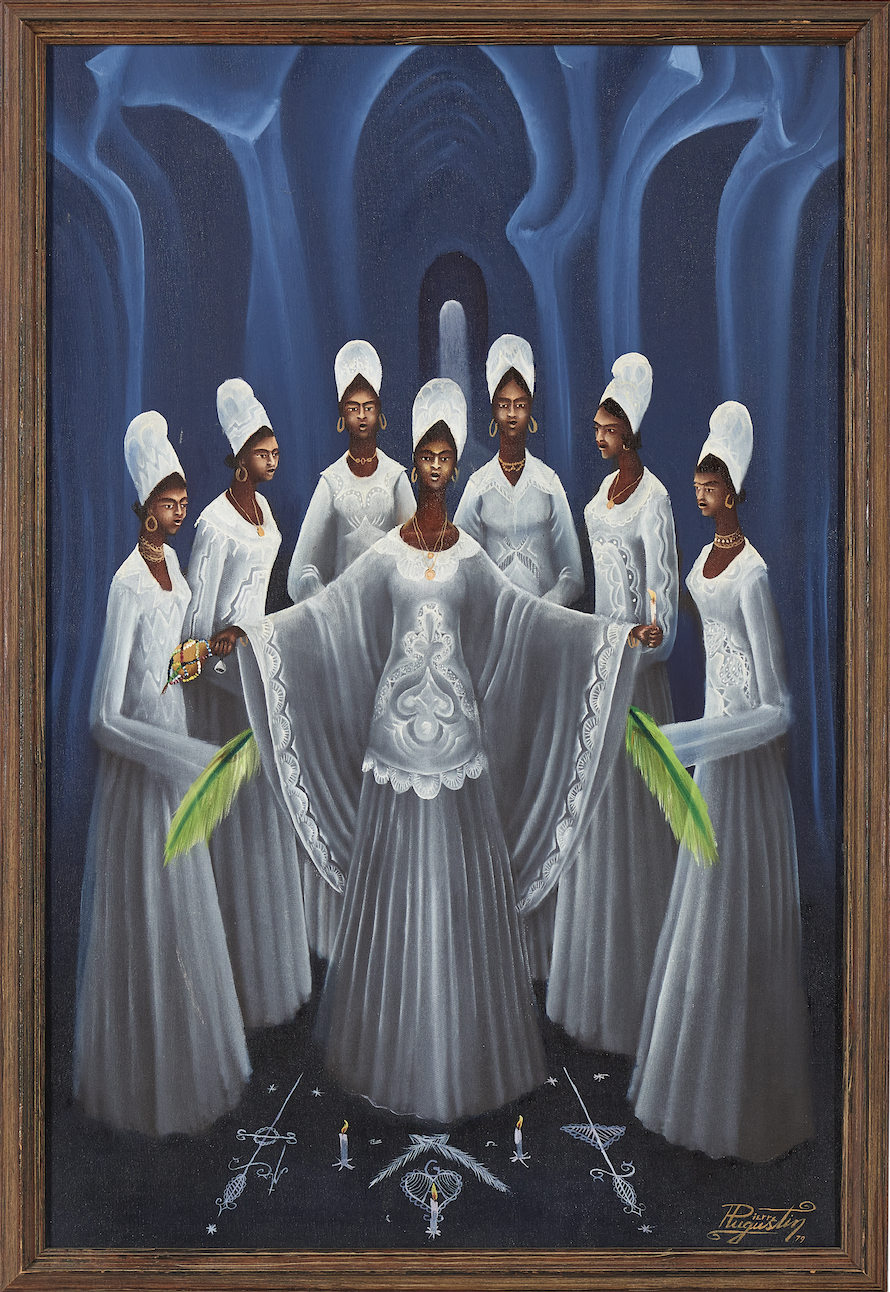

Two renowned artists whose works have been barely discussed in the context of Voudou representation are Pierre Augustin (Haitian, 1945–2014) and Préfète Duffaut (Haitian, 1923–2012). In his 1979 painting Vodou Ceremony (fig. 3), Augustin portrayed a gathering in which a mambo (Vodou priestess) leads her initiates in a ceremony. The practice of ancestral worship, a foundation of many African and Indigenous religions, teaches that the African path to freedom lies in the connection one has to their ancestors and the lwas. This belief system originates from the West African Dahomey, Yoruba, and Ifa religions.25Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, 163. Palm leaves represent the initiate’s connection to the land and the stewardship of nature, key Vodou tenets. The group is performing a ritual to call on the lwa Ezili, a feminine spirit who personifies facets of womanhood.

In this painting, the mambo stands in the center. Dressed in white, she holds an ason (sacred rattle) in her right hand and a candle in her left. She is surrounded by female initiates who are also dressed in white, a color that indicates an initiation. The mambo stands in front of a vevè of Ezili, a symbolic representation of the lwa drawn with chalk or cornmeal that serves as a temporary portal through which the deity travels from the spiritual plane to the physical one to participate in the ceremony. Although Ezili has become visually parallel to her Catholic counterpart, the Virgin Mary, Augustin has avoided the adaptation of integrating Vodou beliefs within a Catholic framework, thereby resisting postcolonial influences.

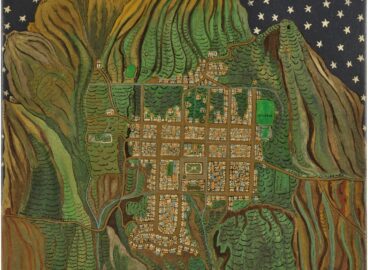

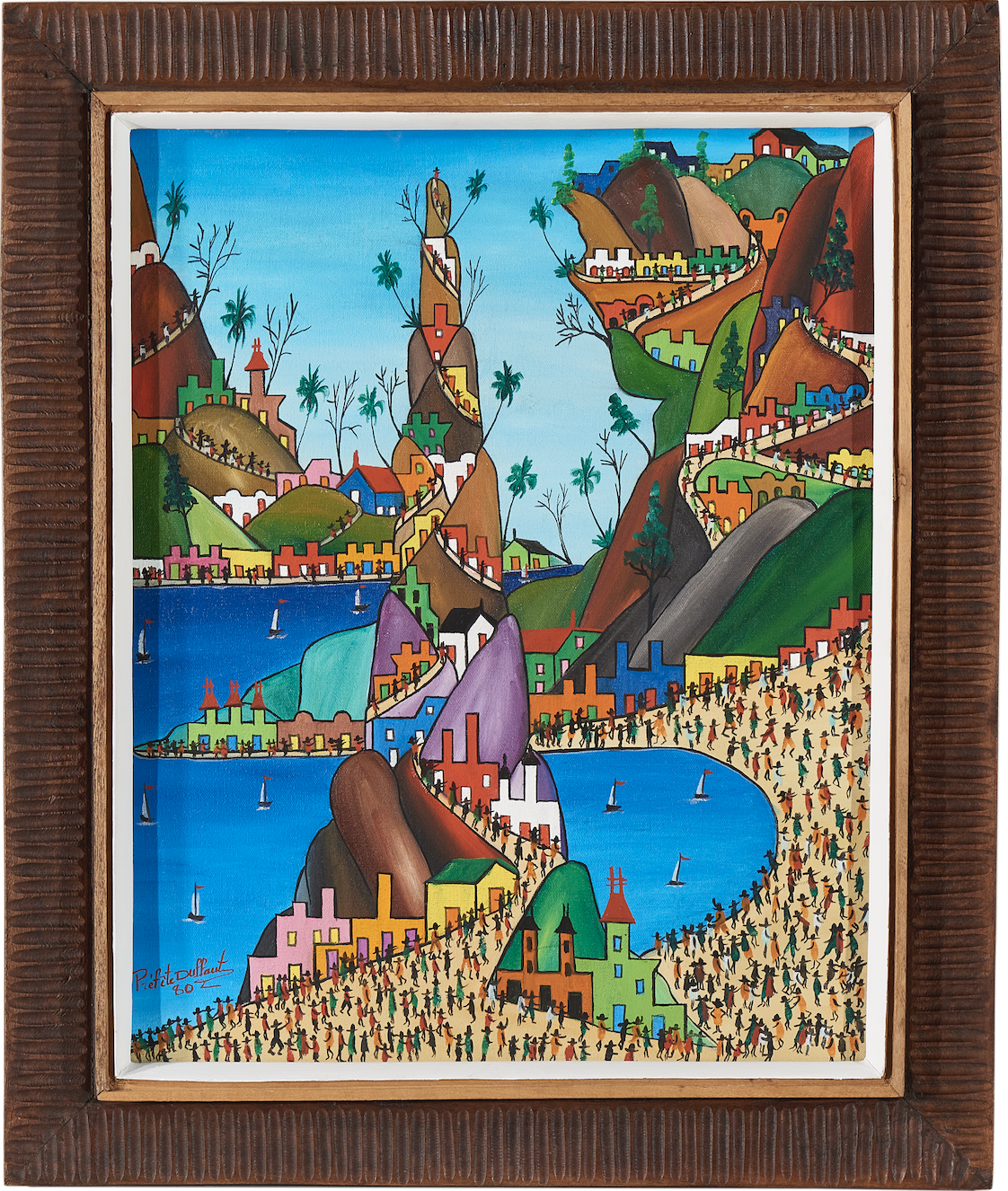

A prominent figure in Haitian painting, Duffaut was born in 1923, when Haiti was under US Occupation. In 1944, he met the painter Rigaud Benoit, who was scouting artists for the Centre d’Art. According to Robert Brictson, although all accounts indicate that Duffaut was a practicing Catholic, his paintings of imaginary cityscapes feature strong Vodou representation.26Robert Brictson, “On Préfète Duffaut,” 100–113, in Kafou: Haiti, Art and Vodou, ed. Alex Farquharson and Leah Gordon, exh. cat. (Nottingham Contemporary, 2013), 104. Duffaut states that a vision of the Virgin Mary inspired his vocation as a painter. In Vodou City (fig. 4), for example, a bustling beach community surrounded by mountains, with ribbons of paths and roads weaving throughout, allows for a reimagining of identity and community in a modern context. In the center of the painting, a mountain stands alone, possibly representing the poto-mitan (center pole) that symbolizes the sacred presence of Bondye (God) in Vodou ceremonies. The recurrent representation of an immense number of people—one of Duffaut’s visual signatures—reflects themes of inclusion and the connectivity of Vodou. Duffaut’s work implicitly explores spirituality, history, and mythology, while simultaneously embodying a broader narrative that envisions a future cultural legacy.

Overall, the interplay between sanctuary and silence in the context of Haitian Vodou art is a poignant reminder that cultural expression can be simultaneously protected and marginalized. Scholar Kyrah Malika Daniels cautions that Western thought does not understand the plural and public role of the Vodou practitioner: In defining the “plural and public spirit pantheon,” she explains that “Vodou devotees do not exist as individual selves, but rather as a multitude of souls.”27Kyrah Malika Daniels, “Vodou Harmonizes the Head-Pot, or, Haiti’s Multi-soul Complex,” Religion 52, no. 3 (2022): 363, 359–83, https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721x.2021.1963877. Though museums serve as sanctuaries for sacred objects, providing spaces for appreciation and recognition, they risk oversimplifying or overlooking the complexities of Vodou artists’ contributions—as well as those of other religions.

As we celebrate the resurgence of Haitian culture in contemporary discourse, we must continue to confront the enduring challenges—to ensure that the voices of Vodou practitioners are not only amplified but also understood and to dispel the stigma associated with Haitian Vodou. In curating themes around Haitian Vodou, museums must engage directly with practitioners, to invite them to contribute to the exhibition being presented and even, possibly, to serve as docents. It is essential to acknowledge the rich tapestry of history, artistry, and spirituality that Haitian Vodou embodies, securing a proper account in museums and within the broader context of global art and culture. Museums can ensure that the sacred aspects of Vodou are preserved and adequately represented alongside the contemporary aspects of Haitian art by documenting and contextualizing the design and purpose of individual objects in sacred spaces. Today, museums such as the Waterloo Center for the Arts and the Figge Art Museum in Iowa and the Milwaukee Art Museum focus on incorporating the Vodou narrative that was culturally omitted over time. Collaborating with experts in this religious practice and its cultural expression, they offer more in-depth perspectives through curatorial initiatives that focus on diverse themes and the surrounding world of Haitian art, particularly Haitian Vodou. It is my hope that more institutions will follow suit and consider how curators and other professionals can amplify the cultural promotion of sacred art.

- 1Kate Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law: Vodou and Power in Haiti (University of Chicago Press, 2011), 120.

- 2Carol J. Williams, “Haitians Hail the ‘President of Voodoo,” Los Angeles Times, August 3, 2003, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-aug-03-fg-voodoo3-story.html.

- 3Spirit & Strength: Modern Art from Haiti, National Gallery of Art, September 29, 2024–March 9, 2025, https://www.nga.gov/exhibitions/spirit-strength-modern-art-haiti.

- 4Lawrence Witchel, “Haitian Primitives: From Art Form to Souvenirs,” New York Times, September 8, 1974, https://www.nytimes.com/1974/09/08/archives/haitian-primitives-from-art-form-to-souvenirs-art.html. Popular indicators of Vodou imagery include ceremonial objects such as the rattle as well as key deities and figures.

- 5Dowoti Désir, “Vodou: A Sacred Multidimensional, Pluralistic Space,” Teaching Theology & Religion 9, no. 2 (2006): 93.

- 6Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law,24.

- 7Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy (Vintage, 1984), 172.

- 8Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law,43.

- 9Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, 176.

- 10Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law, 51.

- 11John Merrill, “Vodou and Political Reform in Haiti: Some Lessons for the International Community,” Fletcher Forum of World Affairs 20, no. 1 (1996): 42, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45288959.

- 12Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law, 51.

- 13Jean Price-Mars, So Spoke the Uncle, trans. Magdaline W. Shannon (Three Continents Press, 1983), xi.

- 14Michel-Philippe Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt: Haitian Art, 1927–1944,” in “Haitian Literature and Culture, Part 2,” special issue, Callaloo 15, no. 3 (1992): 711, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2932014

- 15Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt,” 716.

- 16Lerebours, “The Indigenist Revolt,” 716.

- 17Ramsey, The Spirits and the Law, 197.

- 18Eleanor Ingalls Christensen, The Art of Haiti (Art Alliance Press, 1975), 44.

- 19Christensen, The Art of Haiti, 50.

- 20Marta Dansie and Abigail Lapin Dardashti, “Notes from the Archive: MoMA and the Internationalization of Haitian Painting, 1942–1948,” post: notes on art in a global context, January 3, 2018, https://post.moma.org/notes-from-the-archive-moma-and-the-internationalization-of-haitian-painting-1942-1948/.

- 21Christensen, The Art of Haiti, 51.

- 22Christensen, The Art of Haiti, 52.

- 23Merrill, “Vodou and Political Reform in Haiti,” 45.

- 24Mambo Chita Tann, Haitian Vodou: An Introduction to Haiti’s Indigenous Spiritual Tradition (Llewellyn, 2012), 43.

- 25Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, 163.

- 26Robert Brictson, “On Préfète Duffaut,” 100–113, in Kafou: Haiti, Art and Vodou, ed. Alex Farquharson and Leah Gordon, exh. cat. (Nottingham Contemporary, 2013), 104. Duffaut states that a vision of the Virgin Mary inspired his vocation as a painter.

- 27Kyrah Malika Daniels, “Vodou Harmonizes the Head-Pot, or, Haiti’s Multi-soul Complex,” Religion 52, no. 3 (2022): 363, 359–83, https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721x.2021.1963877.