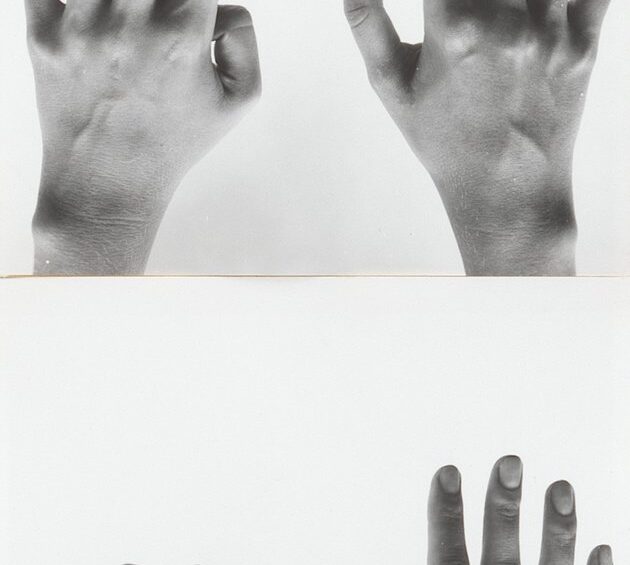

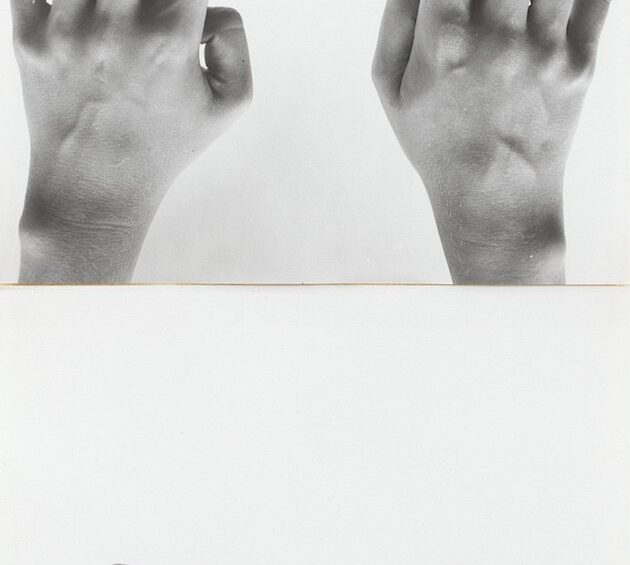

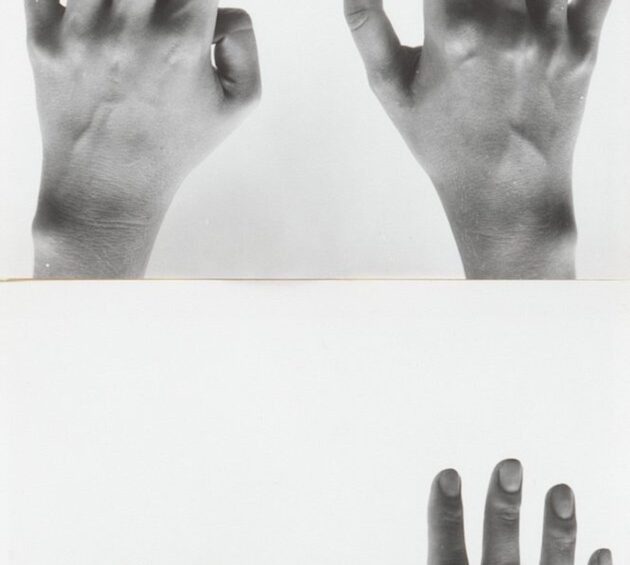

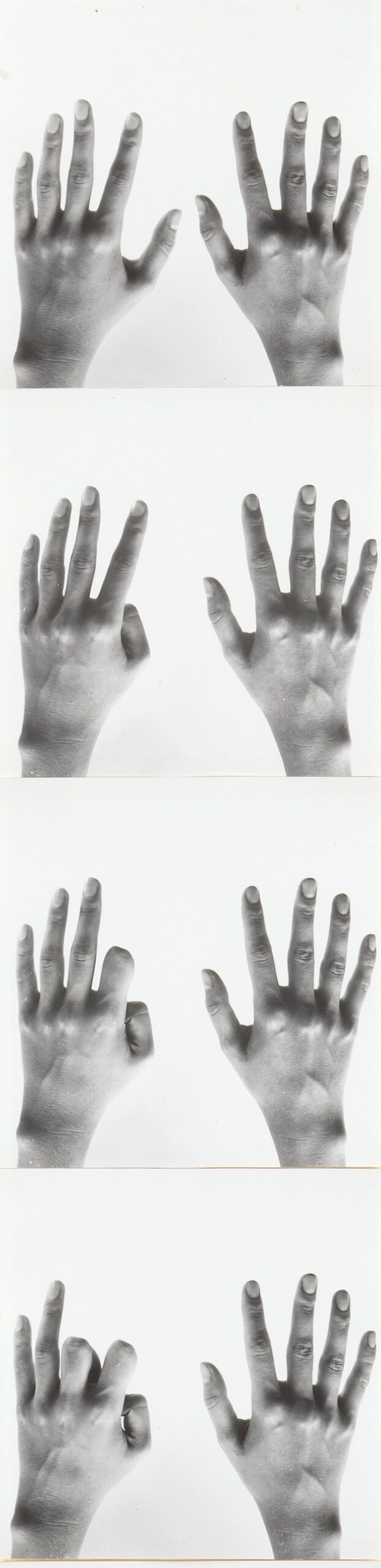

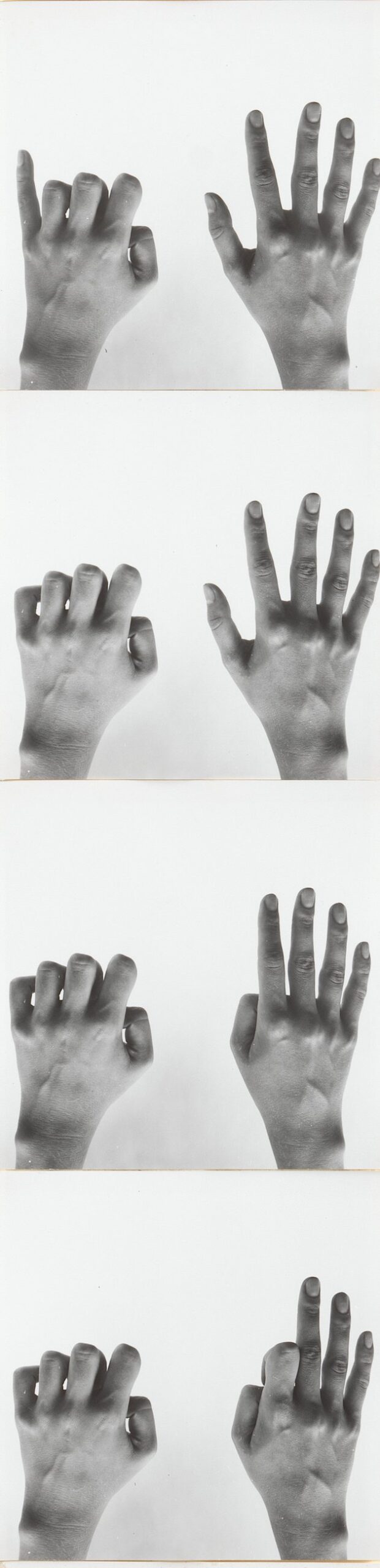

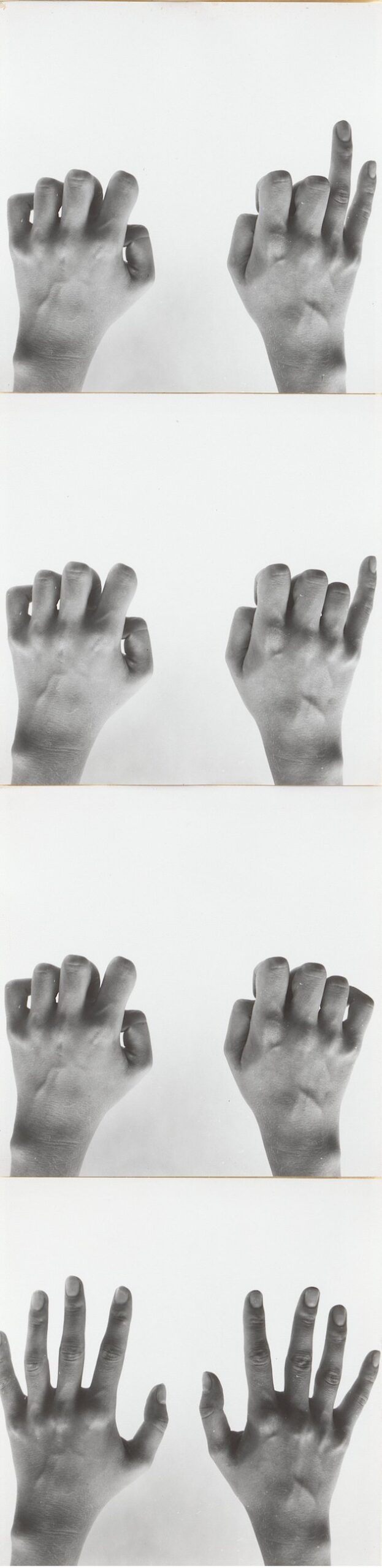

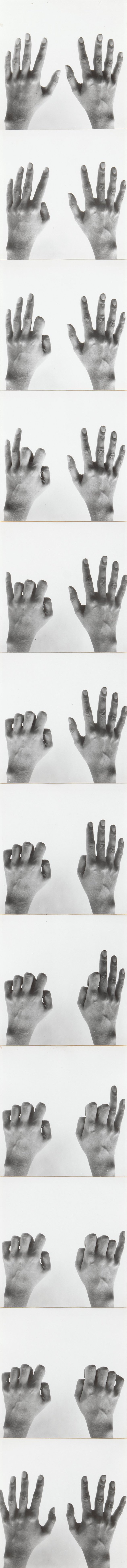

A series of twelve black and white photographs from MoMA’s Photography Study Collection—each depicting a woman’s hands performing various gestures against a neutral background—have recently been the focus of renewed scholarly interest at the Museum. The prints, grouped in three sets of four and attached to one another with transparent tape, compose three vertical columns of closely related images. No text or explanation is included apart from a hand-written inscription on the back of one of the photographs: “Zbigniew Dłubak / Warsaw — Poland / 1971.”

This information helps us trace the work’s origin to an early conceptual project by the Polish postwar photographer and art theorist Zbigniew Dłubak (1921–2005). The work is from the series Gestykulacje (Gesticulations), which consists of images that aim to deconstruct our common visual perception of the human body by depicting fragments of the female body. In MoMA’s version of the work, a woman’s hands are shown forming unfamiliar signs that seem intended to convey meaning (one might, for example, assume that these hands depict a person counting), although the precise message is elusive. At the foundation of the work lies the artist’s aim to deconstruct the body both as a physical entity and a concept. Fragmented, broken down into confounding systems, the human form resembles nothing so much as a sequence of shapes, modules, and gestures.

Zbigniew Dłubak’s practice was based upon an assertion that art, as a humanistic enterprise, is inevitably dependent on a certain intellectual control: “Artistic work is an interrogation of art,” he once said.1Alicja Kepinska, Nowa Sztuka: Sztuka Polska w Latach 1945-1978, Warsaw: Auriga, Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1981: 137. Consequently, rather than following the path of Art Informel—the dominant art movement in Poland in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Dłubak embarked on a long-term ontological investigation of art’s meaning. He argued that the notions of sign and referent, as understood in spoken language, are not predetermined in art and are thus continuously open to fresh interpretation. A search for ways to eliminate subject matter and provide viewers with tools to interpret signs in all their ambiguity was at the heart of Dłubak’s methodical, analytic practice. Viewers’ experience of the work was to result from the layers of meaning that accumulated while they engaged with it.

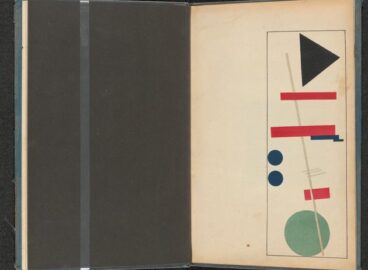

A self-taught painter, Dłubak developed an interest in photography after the World War II and made his photographic debut in 1947 with an exhibition of experimental works. In 1953, he became editor of the monthly magazine Fotografia (Photography), a position he held until 1973. Technically assured (Dłubak developed his artistic practice since the late 1940s), he leaned toward conceptualism. His 1967 project Ikonosfery (Iconospheres) marked his first first attempt to visually examine the physical qualities of a female body into seemingly unrelated parts. The resulting works were hung both inside and outside Warsaw’s Galeria Współczesna. The artist’s focus on women (Ikonosfery never featured images of men) seems to be motivated by the artist’s deep interest in female body, but also explicitly places Dłubak’s practice within a larger art historical context. Contrary to traditional artistic depictions of women that venture to exemplify the essence of female beauty (think Titian and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres in painting and later Edward Steichen in photography), Ikonosfery II (1968) and Ikonosfery III (1970) show deconstruction and multiplication of the female body, leading to compositions that are almost entirely abstract, made up of barely recognizable forms. Subjects depicted in the photographs lose their identity, representing largely de-humanized combinations of visual forms.

Dłubak’s early 1970s Gestykulacje were developed through careful, disciplined study to encourage viewers to question conventional ways of interpreting what they see. His work offers each of us an opportunity to determine meaning independently, an ability that we can understand as ultimately fulfilling Dłubak’s ontological goal.

- 1Alicja Kepinska, Nowa Sztuka: Sztuka Polska w Latach 1945-1978, Warsaw: Auriga, Wydawnictwa Artystyczne i Filmowe, 1981: 137.