In 1975, near the end of the Cultural Revolution in China, artist Xu Bing relocated to the countryside for two years. The 1987-8 woodcuts in MoMA’s collection reflect this pastoral atmosphere while anticipating the artist’s later turn to Conceptual art.

The set of woodcuts by Xu Bing (Chinese, born 1955) in MoMA’s collection depicts rural scenes. It was printed in 1987 and 1988—exactly the time that Xu turned from pictorial representation to repetition through printing techniques. Since it constitutes the first series of conceptual prints that he developed, it yields a key to understanding the artist’s larger transition from his early print works to his later conceptual art practice. Xu Bing is often associated with the grandeur and sacred space of his signature work Book from the Sky (1987–91), which presents thousands of printed pseudo-Chinese characters in the formats of scrolls and traditional books, but he is also well-known for his cultural critique in the performance Cultural Animal (1994), in which a pig, tattooed with false Chinese characters, reacted in a sexual manner to a life-size, tattooed (with invented English words) mannequin in human form. Works such as these have made Xu a representative figure of the “Chinese avant-garde.”

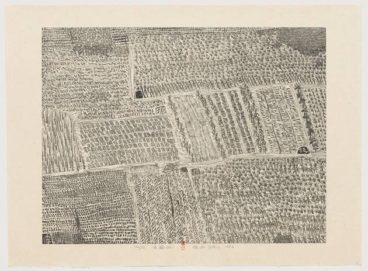

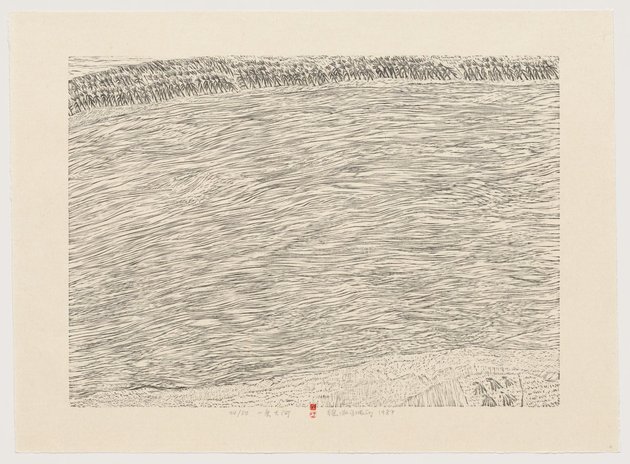

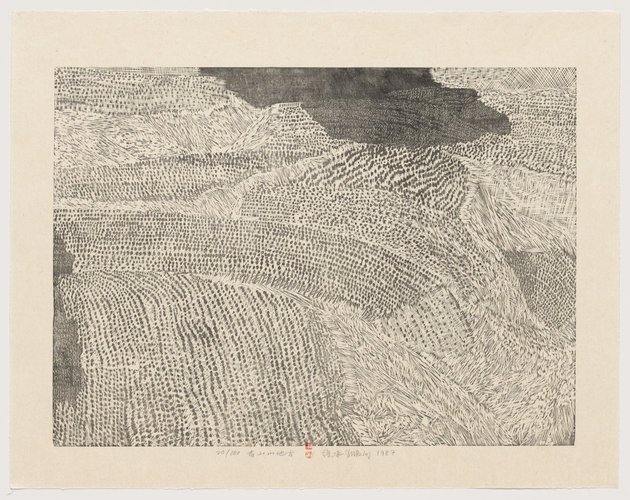

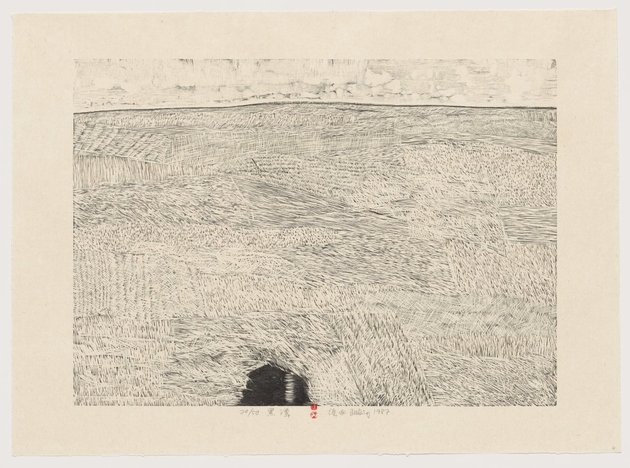

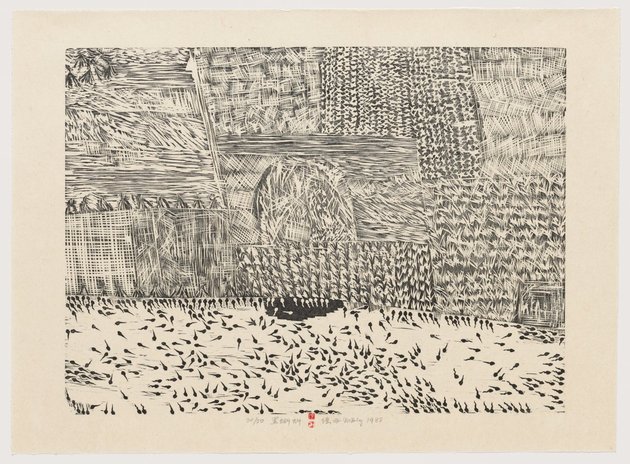

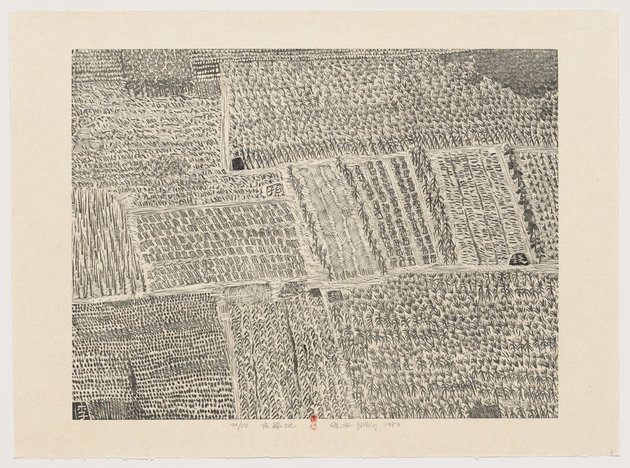

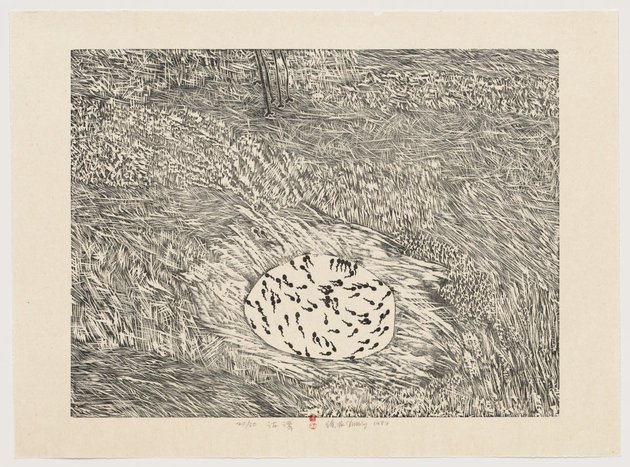

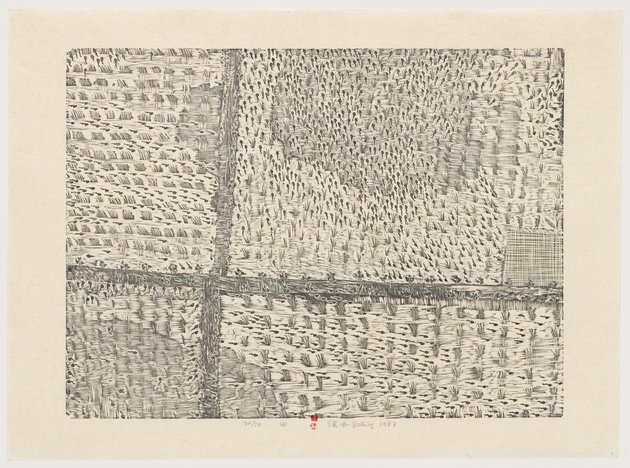

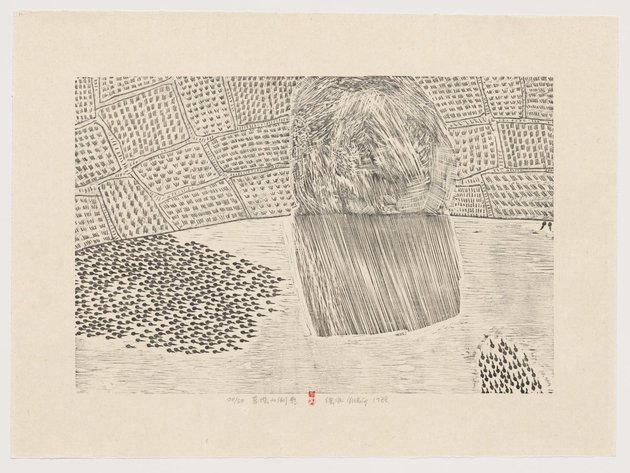

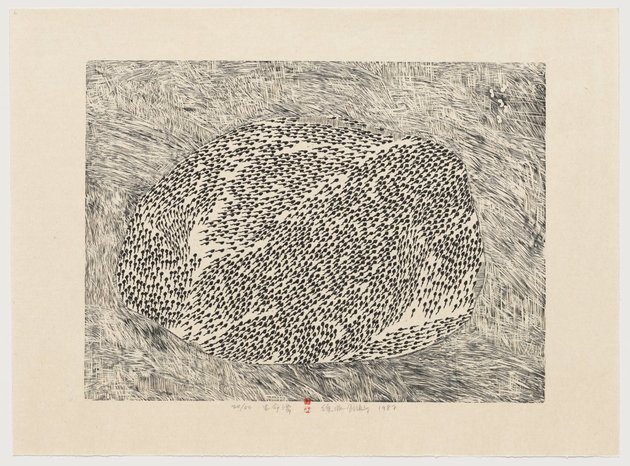

The titles of the prints in MoMA’s collection, Black Tadpoles, Haystack Reflection, Moving Clouds, Life Pool, A Mountain Place, and Cropland, to name a few, recall the rural life that Xu experienced before he entered the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Like many young students who sought out the countryside as a result of Mao’s rustication, Xu volunteered in 1974 to work with peasants after finishing high school.1Most schools and universities were shut down during the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1976. In 1968, Mao announced that urban youth should be sent to the countryside for reeducation. They became important labor help. Besides a youthful utopian affinity for socialist ideals, there were other reasons for this decision: Xu’s father was on the faculty of the Department of History of Peking University and his mother worked in the library. As a result, the family was attacked during the Cultural Revolution for being part of the bourgeoisie who are enemies of the communist society. In hopes this designation would not become a stumbling block when he applied for admission to the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Xu conformed to Mao’s policies. He was admitted into the Academy, but his family history kept him cautious throughout his time there. Haystacks, fields, farm cottages, and crops were dominant motifs in his prints from the early 1980s, a series he later named “Shattered Jade.” These works are smaller in scale, with determined lines, and they sometimes represent an analogous relationship between the natural landscapes and hieroglyphs. They are no doubt drawn from Xu’s personal iconography, but, more importantly, they are politically correct and echo Chairman Mao’s 1942 announcement that art is made for the people.

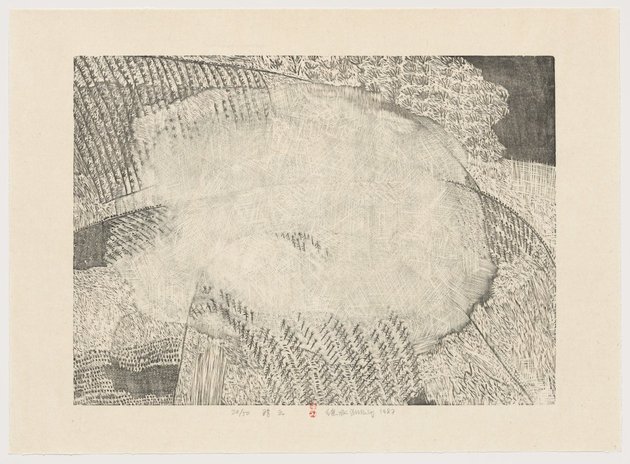

The series of ten prints in MoMA’s collection show a similar abstracting of the landscape into flat, textured fields, but the contour lines are less determined and attempts at correcting earlier marks are visible. For example, the square in the bottom right of the first print seems abrupt and the strokes that constitute the fields decenter the composition. The characters which stand for common Chinese names — Zhao, Qian, Sun, and Li that appear in the ninth print — are rendered in a rough, absent-minded manner, as if produced by a poor calligrapher. The freedom in the compositions and indelicate draughtsmanship give the set a straightforward beauty—a quality more characteristic of sketches than of prints — due to the fact that Xu used his carving knife to sketch directly into the block, rather than working from a tracing. Although there is repetition of motifs such as fields and tadpoles within the series, the size of the blocks and the paper used differ from one print to the next, indicating that the ten prints were not originally conceived as one unit. Rather, they were selected from experiments and studies for Xu’s Five Series of Repetitions (1987–88) and were only grouped together later on.

Originally the complete set of Five Series of Repetitions illustrated the process of woodblock carving in its entirety, starting with a bare block and ending with an almost completely carved-away surface. Xu made prints at regular intervals during this process, recording the gradual reduction of the woodblock and its corollary additions and deletions on the printed page. Five Series of Repetitions is usually displayed in a sequence that emulates a long scroll, and so the work unfolds as a process from nothing to something and then back to nothing again.

Although the ten prints in MoMA’s collection do not illustrate this process, their abstracted landscapes nonetheless illuminate the artist’s attempt to move away from representation. From 1987 to 1988 Xu was exploring the possibilities of printmaking, and specifically what could be termed conceptual printmaking. The conceptual aspect is reflected in the exploration of repetition in the printing process—basic elements such as dots and lines are repeatedly carved with subtle differences. It was during this exploration that Xu developed the method for creating Book from the Sky, in which he created thousands of pseudo-Chinese characters printed from wood letterpress type. The characters were based on his study of traditional fonts and the radicals (different elements of Chinese characters) that are conceived as part of an overarching composition. According to this modular system, certain elements, such as a stroke, recur and enter into new relationships with elements in other characters. Through this repetition, Xu created around one thousand characters for a room-size installation that is unreadable yet nevertheless prompts viewers to attempt to decipher it.

In “The Path of Repetition and the Imprint,” written in 2009, Xu retrospectively concludes that it was during the act of making the woodblock for Series of Repetitions that he really came to master the woodblock process.2See Xu Bing, Xu Bing Prints (Beijing: Culture and Art Publishing House, 2010), 6–11. This set of prints also marks his turn toward conceptual art—a turn from nothing to something and back to nothing again.

- 1Most schools and universities were shut down during the Cultural Revolution, from 1966 to 1976. In 1968, Mao announced that urban youth should be sent to the countryside for reeducation. They became important labor help.

- 2See Xu Bing, Xu Bing Prints (Beijing: Culture and Art Publishing House, 2010), 6–11.