Maya Varma: To begin, I wanted to talk about where you come from. How has Mumbai shaped you as an activist and as an artist? What did the city mean to you growing up?

Shrujana Niranjani Shridhar: For me, Mumbai has always been a working-class city. That’s its defining character. Any city that grows because people come there to work develops certain things: functional public transport, cheap food, spaces you can access without feeling excluded. Rent is expensive, of course, but life around you feels reachable. That accessibility shaped my childhood. I was constantly out—taking buses and trains on my own by age eight or nine. That kind of mobility gives you agency that stays with you, especially for a girl in India (fig. 1).

I also grew up in a very political home. My parents are Ambedkarite, Marxist, anti-caste people who fought hard for their education, and their politics shaped everything in our house. My family has been in Mumbai for a couple of generations, so our relationship to the city is deep. Even with the gentrification happening now, it is still hard for me to be angry at Mumbai. There was a time when the city felt like it was truly ours. We could sit by the sea, go to the aquarium, the museum, the planetarium. My parents took me everywhere, and that exposure shaped me into someone who is always thinking and asking questions.

Mumbai also gave me a visual language. It did not come from galleries, because there were not many accessible ones then. It came from the trains, the sea, the political culture of Maharashtra, the literary tradition of essays, theater, poetry, and also from the vibrance of the music we grew up with. There was a kind of freedom in those moments, even if it was never fully available to Dalit girls in the same way. That tension between what we desire and what we can access has shaped how I look at the world.

MV: You were also growing up during an intense political moment in the city, with violence unfolding around you while the country projected a very different public narrative. As your political commitments deepened, how did this dissonance shape your sense of responsibility as an artist?

SNS: I was born in 1992, so all the politics of that time were simply the atmosphere of my childhood. Babri happened shortly after I was born, the Bombay riots happened right after, and the 1990s and early 2000s were ripe with bomb blasts and communal tension.1In December 1992, the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya (northern India), was demolished by Hindu nationalist groups. The event sparked widespread communal violence across the country, including the Bombay riots, and marked a turning point in the rise of Hindu nationalism in India. It became normal for us. You would be waiting for a train or a bus, hear that a blast happened somewhere else in the city, and then you would just go home. Everyone who grew up in Mumbai in the ’90s lived with that kind of violence.

At the same time, mainstream media kept presenting a very liberal idea of unity and diversity. Those were the images painted everywhere, even though the reality around us was completely different. When I think about it now, it feels absurd that this is what we accepted as normal. But that environment shaped how I thought about culture and what it means to make something that cannot be twisted or misunderstood later.

As someone from a marginalized community, I’m never only an artist. I’m always thinking about the past that shaped my family, the present I’m trying to make sense of, and the future I want to help build. My work has to hold all of that. That’s why I don’t respond immediately to events around me. My practice needs time to research, to understand what already exists, and to be intentional about how I represent myself and my community.

I also know now that I am someone who needs to be liberated. I’m part of the community I’m speaking from. For me to work honestly, I have to understand what my own body carries: my grandmother’s experiences, my sisters’ experiences, my friends’ experiences. All of that moves through me, and processing it takes time. I’m always thinking about posterity. I don’t want a future where culture looks back at us and gets it wrong. I can’t control how the present sees us, but by making the work I make, I’m putting something into the present that I hope the future will understand clearly. There should be no mistake.

MV: I’d like to turn to the portraits in your new series Educate, which takes these questions around representation into the lives and lineages of Dalit women. How did that project begin, and what does “educate” mean for you in this context?

SNS: Educate is the first part of a three-part series I began about a year and a half ago. The title comes from the first word in [the slogan] Shika, sanghatit vha ani sangharsh kara—which is usually translated as “educate, agitate, organize.”2“Shika, sanghatit vha ani sangharsh kara” is a Marathi political slogan attributed to B. R. Ambedkar, widely circulated within Ambedkarite and Dalit movements in Maharashtra. It is commonly translated into English as “Educate, Organize, Agitate,” and has served as a foundational call linking learning, collective organization, and political struggle within anti-caste activism. But shika is often misunderstood, and it actually means “learn.” “Educate” in English can sound like teaching others, but I’m thinking about learning in a much broader sense: the knowledge systems Dalit communities have built, the violence students have endured, and the determination with which they continue to pursue education. I’m not trying to glorify that struggle; I’m trying to understand what this pursuit of knowledge has meant over a very long time.

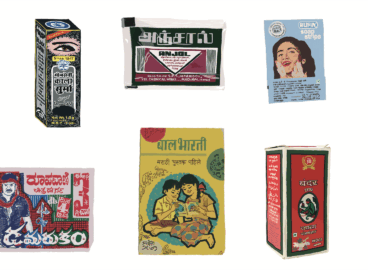

For us, learning has always been taken seriously as a way out of poverty and caste oppression. Even if literacy rates are lower than the national average, the numbers themselves are remarkable given what people have been put through. Culturally, there is a very specific emphasis on education. At our events, there are always books, pamphlets, translations. At Chaityabhoomi on December 6, people spend their hard-earned money on literature and art.3Chaityabhoomi is a memorial site in Mumbai marking the cremation place of B. R. Ambedkar (1891–1956), the principal architect of the Constitution of India and a central figure in the anti-caste movement. Every year on December 6, the anniversary of his death, hundreds of thousands of people, particularly from Dalit and Ambedkarite communities, gather there to pay respects, exchange literature, and participate in cultural and political events centered on education and social equality. These are things supposedly meant for the elite, yet everyone wants to learn something—or at least to hold onto that aspiration.

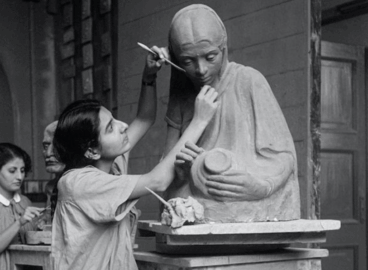

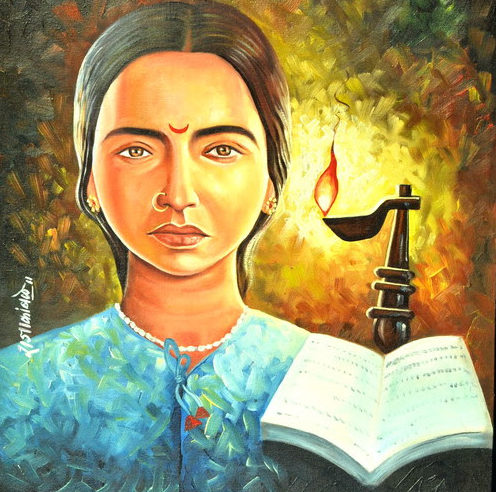

All of this brought me to Mukta Salve (fig. 3). In 1855, when she was only 14, she wrote “About the Grief of the Mahars and Mangs” in the Marathi journal Dnyanodaya. It’s one of the earliest published anti-caste texts by a Dalit girl. The essay is painful, but it’s also full of a sharp awareness that education is the only way out of enslavement. Ambedkar repeated her points about half a century later. So for me, Educate has to begin with Mukta Salve.

MV: Instead of depicting Salve directly, you’ve chosen to paint her “descendants,” the people in her intellectual and political lineage. How did that idea take shape for you?

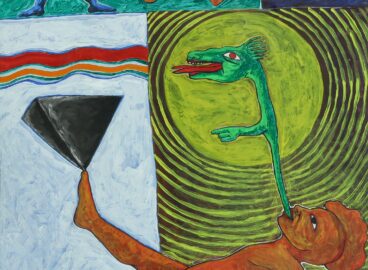

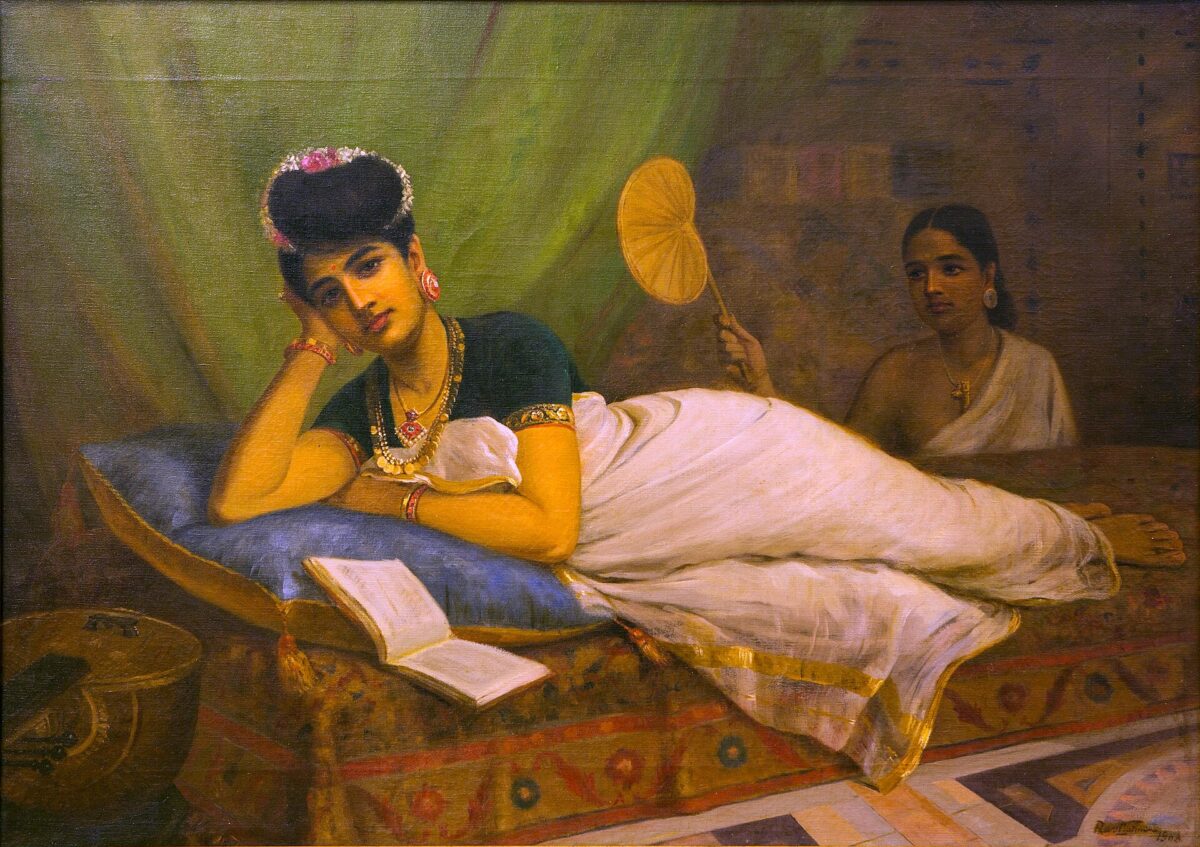

SNS: When I looked at the few visuals that exist of Mukta Salve, there’s really just this one image that circulates. And it doesn’t sit right with me. Beautiful as it is, it feels like it’s coming directly from the lineage of Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906)—those soft, “divine” upper-caste aesthetics rooted in colonial art pedagogy. Ravi Varma painted women from oppressor-caste households into these ethereal, gentle embodiments of “sacredness,” and those images went on to define what an “ideal Indian woman” or “goddess” looked like (fig. 4). That visual language wasn’t built from our lives; it was built from theirs.

So when I look at that image of Mukta Salve, it doesn’t feel connected to who she might have been, or what she wrote, or the conditions she was writing from. It’s an aesthetic that isn’t ours. I did think for a moment, “Should I try to paint her?” But what would be the point of that? For me to sit here and imagine her face… I don’t know what that activity does or what it gives to the work, or to us as a culture.

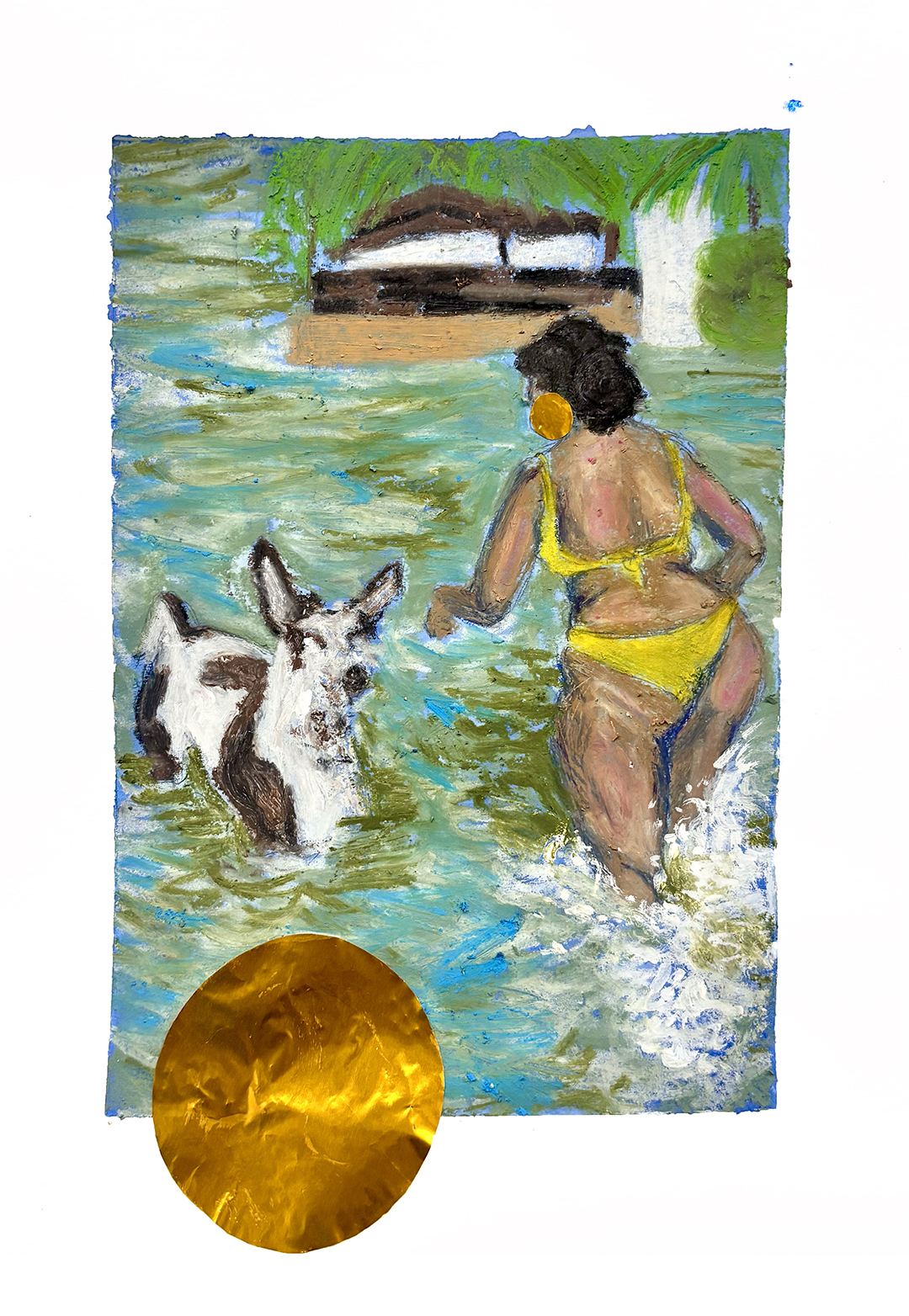

I instead began thinking about Dalit women and girls who are pursuing education now—the people who are carrying her legacy forward. And I wanted the portraits to be a space of release for them, not a re-creation of a historical figure we can’t accurately imagine. That’s how I started painting my friend Divya, who is doing her PhD in New York (fig. 5). The titles themselves will hold that connection between her and Salve, something like Divya in lieu of Mukta Salve, or Mukta Salve’s Divya. The two women are tied together in the work—not visually but conceptually. Divya becomes a way of thinking about what Mukta Salve made possible and what it means for Dalit women to pursue knowledge today.

MV: In the portrait of Divya, the pose of rest feels central. Rest has a very specific lineage in Western portraiture, often idealized through the bourgeoisie. How were you thinking about rest in this context?

SNS: Divya wasn’t posing at all. I spent the day with her, waiting to see when she would finally stop moving. And, at one point, she just sat down. If you look closely, there’s a scowl on her face. It’s not rest. It’s a five-minute break in a full day of labor. That moment is important because portraiture usually puts something on a pedestal: dignity, beauty, power. Here, I wanted to put that tiny, vulnerable pause on a pedestal. That’s the release I’m talking about.

The patterns in the painting do specific work too. The couch pattern comes from the crops grown on Divya’s family’s land. They are literally what she rests on, generationally and materially. The blanket is the exact sari her mother wears in a photo Divya showed me. Divya doesn’t like keeping direct references to her home because the distance becomes too painful, so I brought her mother in indirectly, through pattern. Because her mother is central to Divya’s rest.

And the vulnerability of her pose exists only because of my relationship with her. This is based on a photograph, not a sitting. If she were sitting for me, the softness would disappear, and it would become labor again. That’s why it matters that she wasn’t performing. She was simply tired. And my work is to take that moment and magnify it.

MV: When I visited your studio, you were also working on a portrait of a woman in a bathtub. It felt like a very different kind of scene—still intimate, but coming from another set of questions. Could you talk about what you’re exploring there?

SNS: Yes. That portrait is still very unresolved. It’s of my friend Hrithik, who’s doing her PhD in Minneapolis (fig. 6). She had just moved to the US, and we were talking about how suddenly you have bathtubs everywhere. In India, you don’t. A bathtub is such an aspiration— a marker of “you’ve made it.” And then we started talking about bubble baths—how much guilt there is because of the water, and how strange it feels to allow yourself that kind of pleasure. And from there, we were talking about what we allow ourselves as Dalit women, and what we don’t.

She’s very young. And right now, she’s in this moment of “I’ll do whatever I want. I’m going to have fun. I don’t care what anyone says.” And that takes a long time to arrive at. It might look like normal “young person behavior,” but for her it’s new. She has become young now. That also happened to me—I came into my youth when I was older. When I was younger, I wasn’t young. So for her, this portrait is about exercising agency, claiming the right to live her life as a young person, on her own terms. And for me, it’s also the first time I’m painting someone in this context.

MV: That question of agency feels connected to what you were saying earlier about the series as a whole. Not just rest, but how Dalit women navigate their own representational constraints. How does that come through in this portrait?

SNS: All of these portraits are not only about repose. They’re also about morality and respectability politics, and how those things get imposed on Dalit women’s bodies. Shailaja Paik writes about this: the way Dalit womanhood, through the anti-caste movement, starts to carry an imposed masculinity.4Shailaja Paik, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India: Double Discrimination (Routledge: 2014). We become bodies that are supposed to represent endurance, sacrifice, honor. You never want your body to trigger the tabooed memories of the kinds of labor Dalit women were historically forced into. And that’s a huge burden, because that same body also has desires, sexuality, pleasure. But you cannot express that. You cannot be playful. That’s what we mean when we say, “I didn’t get to be young when I was younger.” Within the anti-caste movement, there is so much respectability politics. Someone will always say: “This is not how someone from our community behaves. You represent serious things, so you must always be serious.” There is no space to be fully human.

And you know, it’s uncomfortable for me too. There are moments when I’m painting and I think, “What am I doing?” These women are simply feeling something, and it doesn’t look overtly political. It doesn’t look radical. But there is a radical edge to it. While I paint, my body has to stay aware of that tension—not only the need to challenge Brahminical patriarchy and Brahminical supremacy, but also the need to challenge ourselves. Art cannot just make us feel represented. It can’t only give us images of Dalit women that confirm what we already know. It also has to push us to ask, “What do we allow Dalit women to do?”

As someone shaped by the anti-caste movement, I have to ask whether I am ready to tolerate women from my community enjoying themselves. Because the moment Dalit women experience pleasure or softness, it’s dismissed as frivolous or unserious. And that dismissal sits on top of generations of emotional, physical, and intellectual labor carried disproportionately by Dalit women. They have carried entire communities, yet are not afforded their own humanity. That’s the challenge this series is trying to hold. If you had told me four months ago that I would be painting someone in a bubble bath as part of Educate, I wouldn’t have believed you. It feels wild. Because the histories around education for Dalit communities are full of violence—the use of water against us, the violence in schools and universities, the experiences of Dalit students navigating institutions designed not to include them. Those histories shape what we imagine “education” is supposed to look like, and you wouldn’t expect these portraits from that imagination.

MV: Especially when you place them in the lineage of Salve’s writing.

SNS: Exactly. To then say Mukta Salve’s Hrithik—that is an immense claim. And yet while the rest of us are tense, she is there, having the bubble bath she deserves. She is in bliss.

MV: Which was the point of Salve’s writing—to carve out the right to live differently.

SNS: This is what I mean when I say my work is about creating the moments we want in the future, in the present. If the goal is equity—that all of us get to enjoy our lives—then shouldn’t we say that we deserve that enjoyment now? That’s the dialogue happening in my head while I make this portrait.

MV: Alongside these portraits, you’re also making an installation for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale that comes out of Educate and its focus on water, violence, and learning. How did that work grow out of the same questions?

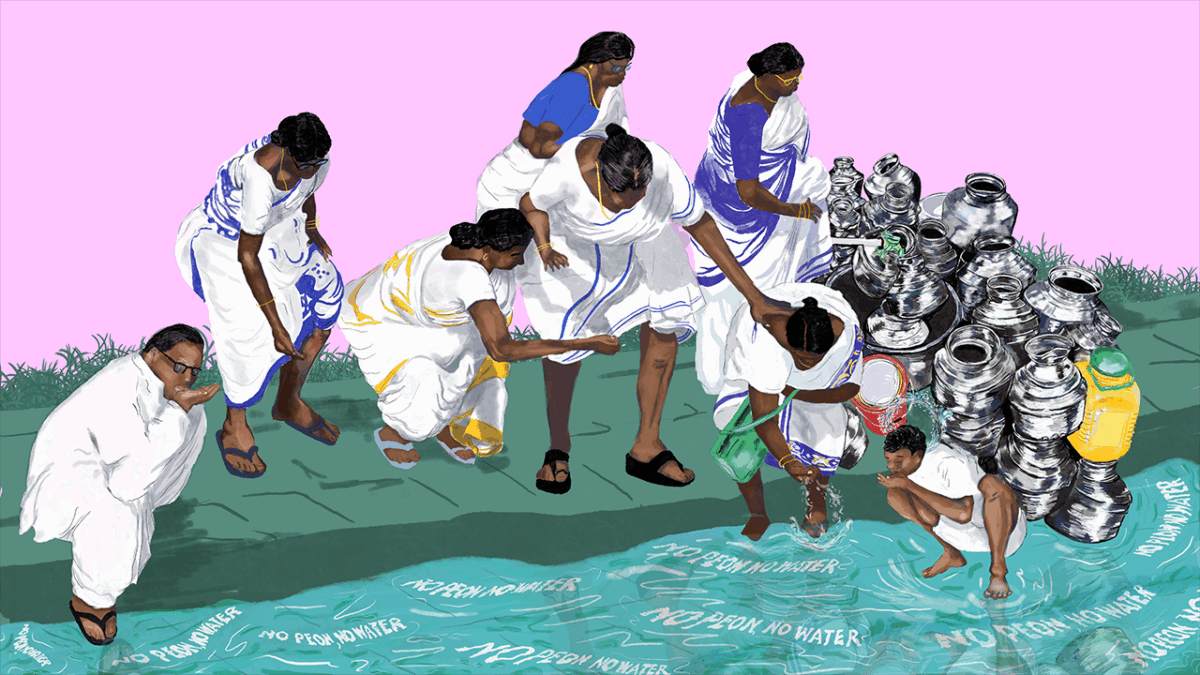

SNS: Last spring, as I was thinking about different aspects of Educate, I started thinking about how water has been used as a weapon and a tool of segregation against Dalit students (fig. 7). Shailaja Paik also writes about this in her work on Dalit women’s education—how, when the British tried to include oppressed castes in schooling, caste Hindus were furious. Their main argument was that if their children studied with us and drank water in the same spaces, their children would be polluted. Water became the most contested site.5Paik, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India.

And it continues. There was a case recently of a boy who drank from his principal’s bottle and was beaten. There was Indra Meghwal, a little child in Rajasthan who drank from the common source in school and was beaten to death by his teacher.6In August 2022, Indra Meghwal, a nine-year-old Dalit student in Jalore district, Rajasthan, was assaulted by his teacher after drinking water from a pot reportedly reserved for upper-caste staff. Meghwal later died from his injuries. The incident was widely reported as a case of caste-based violence rooted in everyday practices of segregation around access to drinking water in schools, prompting protests and renewed discussion of the persistence of caste discrimination within state institutions. See Esha Roy, “Dalit boy dies after being assaulted by teacher for touching water pot, Rajasthan,” The Indian Express, August 15, 2022. I was thinking about the violence that water holds, of water as an archive. I was also thinking about Ambedkar’s experiences in school—No peon, no water—where he could only drink if a school official (peon) poured water for him from a height, and if that person didn’t come, he had no water. Water is the site of humiliation and the site of resistance. After Dr. B. R. Ambedkar’s legendary Mahad Satyagraha in March 1927 at Chavdar Tank, the local caste Hindus were infuriated and decided to “purify” the water using panchgavya (a mixture of cow urine, cow dung, milk, ghee, and curd). Polluting the water in this way was preferred to the mere thought of human beings from a different caste touching it.7In 1927 in Mahad, Maharashtra, Dalits led by B. R. Ambedkar drew water from the Chavdar Tank, a public water source from which they had long been excluded despite its legal status. The event, known as the Mahad Satyagraha, marked a landmark challenge to caste discrimination in everyday civic life. An infuriated Dr. Ambedkar decided to burn the Manusmriti shortly after, on December 25, 1927, at Mahad.8The Manusmriti is a classical Hindu legal text that codifies social hierarchy, including caste and gender norms, and has historically been used to justify caste-based exclusion.

Inspired by this, I wanted to use that same material, water, to destroy the Manusmriti. I started working with unfired clay tiles, roughly A4 or letter size, so they read as “documents.” I went through the Manusmriti and picked verses that specifically talk about education and what should happen if someone from an oppressed caste dares to study, what punishments are prescribed. It was a very painful process to read and select those texts.

I developed these slabs and began printing the verses on them with henna, using a screen-printing process on the wet clay so the text would be very clean and legible. Then I built an installation where water slowly drips onto the tiles (fig. 8). As it keeps dripping, the text dissolves, the clay collapses, and it literally turns to mud.

I also made the tiles as a walkway (fig. 9). You have to step on them to enter the space. It feels like stepping on dry leaves—there’s this very soothing, ASMR-like cracking sound. It’s calming. You hear the water dripping, you feel this relief in your body. And then you look down and read what you’re stepping on, and it hits you like a ton of bricks. That’s the experience I wanted: the calm and the violence arriving together, in your body.

Over time, as people keep stepping, the text becomes less legible. I’m completely okay with that. In fact, I think some of these texts should never be archived. They should not exist. I don’t need to give you evidence of the atrocity; the fact that I had to create them just to destroy them should tell you enough. And this is coming from someone who cares deeply about archives, who loves holding on to pieces of history. The work at Kochi via Conflictorium displays only the walkway tiles on a 6 by 10-foot floor space.

MV: You’ve talked about wanting people to encounter this installation alongside the portraits from Educate. How do you imagine that relationship between stepping on the tiles and then seeing these images of Divya and Hrithik?

SNS: I’ve been thinking about the tiles and the portraits as two different but connected bodies of work. Any time someone wants to access the work in Educate and the portraits of rest, bliss, and release, I want them to do this act of stepping on the Manusmriti first. You shouldn’t be able to just walk in and enjoy the leisure of Dalit women without confronting what has been done to us. The tiles become a threshold, and you have to embody that act of destruction at least once. We have done this kind of work—a thousand times over, in a hundred different ways—before we allow ourselves a moment of rest. So as a viewer, at the very least, you have to do this much.

And, as an artist, I also have to be careful not to reproduce that violence endlessly. The water only needs to be poured once. I don’t want to spend my life making and remaking these tiles so that they can be destroyed over and over. As much as it gives me pleasure to destroy the Manusmriti, I also have to liberate myself.

- 1In December 1992, the Babri Masjid, a 16th-century mosque in Ayodhya (northern India), was demolished by Hindu nationalist groups. The event sparked widespread communal violence across the country, including the Bombay riots, and marked a turning point in the rise of Hindu nationalism in India.

- 2“Shika, sanghatit vha ani sangharsh kara” is a Marathi political slogan attributed to B. R. Ambedkar, widely circulated within Ambedkarite and Dalit movements in Maharashtra. It is commonly translated into English as “Educate, Organize, Agitate,” and has served as a foundational call linking learning, collective organization, and political struggle within anti-caste activism.

- 3Chaityabhoomi is a memorial site in Mumbai marking the cremation place of B. R. Ambedkar (1891–1956), the principal architect of the Constitution of India and a central figure in the anti-caste movement. Every year on December 6, the anniversary of his death, hundreds of thousands of people, particularly from Dalit and Ambedkarite communities, gather there to pay respects, exchange literature, and participate in cultural and political events centered on education and social equality.

- 4Shailaja Paik, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India: Double Discrimination (Routledge: 2014).

- 5Paik, Dalit Women’s Education in Modern India.

- 6In August 2022, Indra Meghwal, a nine-year-old Dalit student in Jalore district, Rajasthan, was assaulted by his teacher after drinking water from a pot reportedly reserved for upper-caste staff. Meghwal later died from his injuries. The incident was widely reported as a case of caste-based violence rooted in everyday practices of segregation around access to drinking water in schools, prompting protests and renewed discussion of the persistence of caste discrimination within state institutions. See Esha Roy, “Dalit boy dies after being assaulted by teacher for touching water pot, Rajasthan,” The Indian Express, August 15, 2022.

- 7In 1927 in Mahad, Maharashtra, Dalits led by B. R. Ambedkar drew water from the Chavdar Tank, a public water source from which they had long been excluded despite its legal status. The event, known as the Mahad Satyagraha, marked a landmark challenge to caste discrimination in everyday civic life.

- 8The Manusmriti is a classical Hindu legal text that codifies social hierarchy, including caste and gender norms, and has historically been used to justify caste-based exclusion.