This essay is adapted from a lecture on the strategies of dissidence in East German art by curator Christoph Tannert, who met with members of the C-MAP Central and Eastern European group on June 3, 2016 during a research trip to Berlin.

This lecture was transcribed by Valentine Goldmann.

This lecture is published with thanks to Christoph Tannert. All text and images are courtesy of Christoph Tannert and are for research purposes only.

The focus of this essay, which is based on a lecture I gave to MoMA’s Central and Eastern European group in June 2016, is the exhibition Gegenstimmen. Kunst in der DDR 1976–1989 (Voices of Dissent: Art in the GDR 1976–1989), which opened on July 16, 2016, at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin. Eugen Blume from the Hamburger Bahnhof and I organized this show, which explores the relationships of dissident art and power in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) through a large number of representative works. Dissidence and critical distancing from the state apparatus took a great variety of artistic forms in the former socialist republic. This gathering of “other” art from the GDR asks how Germany’s recent history can be reappraised after decades of sterile East-West comparisons. Who are its real heroes? The exhibition will present the production of an active, dynamic and fearless network of assertive painters, poets, performers, actionists, Super8 filmmakers and jazz and rock musicians who looked for spaces of freedom beyond the reach of the state.1More information can be found on the exhibition’s website. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue with contributions from Tannert, Blume, and many others.

You might be surprised that it took twenty-five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall for such a project to take place. There are many reasons for this delay, perhaps the most significant being that the German government, up to this point, has stressed policies of integration of populations, of cultures—including of East German and artistic elites—

rather than differences. Interestingly, the “official” artists of the GDR are better known today than its underground artists. Another important aspect is that culturally speaking, the GDR maintained close ties to West Germany due to the connections of language and culture. This is one of the reasons why East German underground developments, or unofficial artistic developments, differ significantly from underground developments in other Eastern European countries such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, etc. I want to acknowledge at the outset of this discussion that the more radical avant-garde activities and underground art took place in those countries—in Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and others—and not in the GDR. Even though the younger GDR artists, those at work from the 1970s onward, did attack the system and thus create a lot of confusion, the subculture in East Germany nonetheless remained very German, that is, very protestant, very conventional, and very conservative.

I believe that part of the reason why this is the case is that the German mentality is one characterized by fear, kept in check by the imposition of various organizing principles that somehow repress it. That is not my own interpretation but rather the result of decades’ worth of psychological and sociological research. For instance, unlike in countries such as England or the United States, where there was a much more relaxed attitude toward punks and hippies, in the GDR, if you were a punk or hippie, you were immediately arrested and taken to the police, your hair was cut, and then you were jailed.

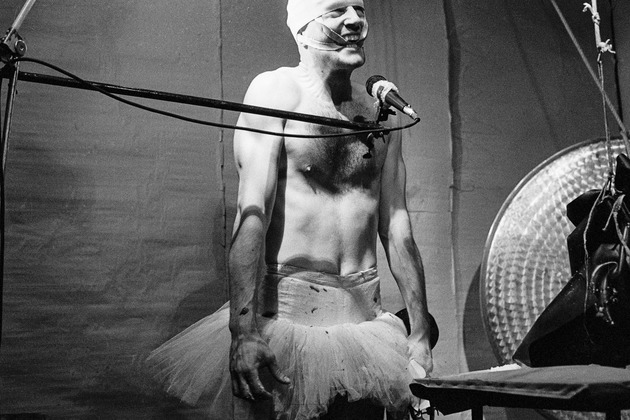

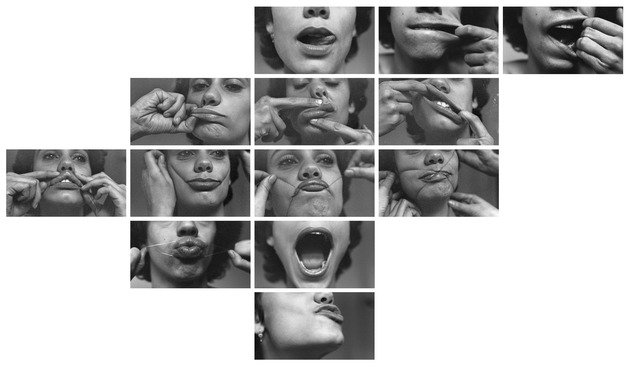

Performance, 1989.

The impetus for the exhibition Voices of Dissent is the fortieth anniversary of the expatriation of Wolf Biermann, a musician and dissident banished from East Germany in 1976. This was the first time that the state powers reacted in such an extreme way to an oppositional figure, and this particular moment marks a shift in the organization of the subculture. There is palpable public concern that the exhibition might impact public perception of the past, that it might somehow change or alter it, and hence the show may not be popular.2This lecture was delivered more than a month before the exhibition opening.

In highlighting images made by artists of the underground, we have attempted to show the realities “on the ground.” One such reality is that East Germany, though controlled by the German Communist regime, was a Soviet-occupied zone for forty-five years, from 1945 to 1990, and that this occupation significantly shaped life for its citizens. Certain works in the exhibition show the militarization of the public sphere and the drabness and grayness of the general atmosphere. On the one hand, the state celebrated as though the utopian promises had already been realized, acting as if the heroes of the proletariat were adored and as if one should be proud of the socialist GDR. On the other, the reality was that life was always contained by barriers, intersected by barbed wire. The state power operated as a sort of dark force that was to be adored and jubilated. The gap between the ideological proposition and the

experienced reality was enormous. A similar situation might be observed today in Venezuela with the bankruptcy of its government.

This image, the one we used for the exhibition poster, is very different. It is a photograph of a 1989 performance by Via Lewandowsky, in which the artist grinds his teeth, and it suggests a slightly more sinister, absurd situation than the official one.

It would be an exaggeration to say that all of the GDR was a labor camp, which is, of course, not true. But the country definitely was restricted by closed borders: there were no visas issued to Western countries and so no possibility of travel there. Travel to the East was more possible, but still difficult. For example, you did not need a visa to go to Czechoslovakia or to Poland—that is until 1981, when martial law was declared in Poland and its borders were tightened. In addition, there were no free elections or free speech in the GDR. Artists made their work, executed their projects, and lived their “counterculture” in their own spaces and underground locations. They literally had to turn dominant culture inside out to do so.

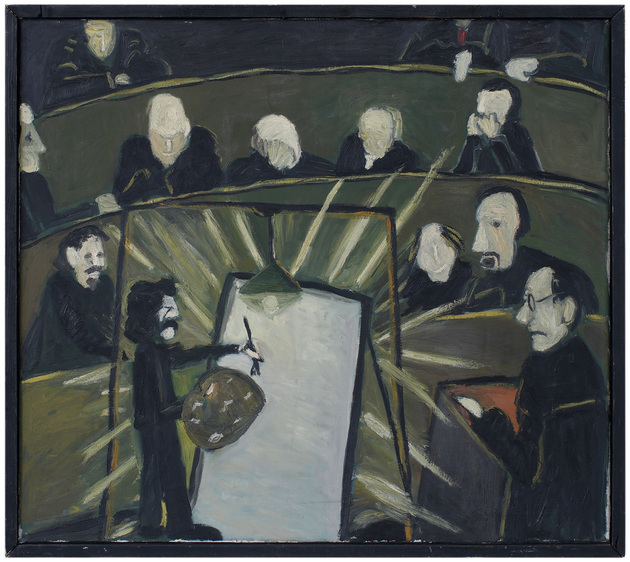

One might see the images of this time as naïve, and in many ways they are, but they are nonetheless true, which is more than can be said of many contemporary pictures. As an example, consider Jury (1967) by Peter Herrmann, who was part of the same circle of Dresden artists as Georg Baselitz, A. R. Penck, and Strawalde (Jürgen Traugott Hans Böttcher) and an important artist of the counterculture. Not only did he introduce a new language, but he also attempted to engage with the larger history of ideas, in this case artistic freedom and censorship.

In Voices of Dissent, we show works by Herrmann and other early works from a private collection, for the first time. They are from the 1960s, and set the context for the main work in the show. One notices that in almost all of the images shown, there is a kind of expressionist urgency, visible in the gesture, in the treatment of the figures and the colors, and also in the way that symbols and metaphors are introduced, reintroduced, and turned upside down. There was historical German Expressionism in the GDR museums, for example the work of the artists of Brücke from Dresden at the turn of the twentieth century and of others. But the new expressionists, the young expressionists of the 1980s, were not initially seen as their inheritors and so were suppressed, their work kept hidden away.

One motif that appears a lot in official East German art is Icarus on his way to the rising Socialist sun. Motifs that recur in work from the underground scene are the Titanic and the carousel. Some of these are meant to be read quite literally. For example, in Lutz Friedel’s Titanic (1982–83), the message is obviously “politics kills.” One must not think of this image as apolitical but rather as highly political. Politics, in this context, must be understood as party politics, or ideological politics.

A surprising number of the paintings made during this time are very small, because small works could be more easily hidden. Often on the surface they look like modest still lifes, as does, for example, Peter Graf’s Alles zum Wohle des Volkes (1980), but in fact they are loaded with references that can be read in different ways; there are multiple narratives and stories embedded within them, along with humor and cheekiness. For instance, the slogan in the background translates, “Everything for the good of the people,” but half of the letters in the words making up the sentence are missing.

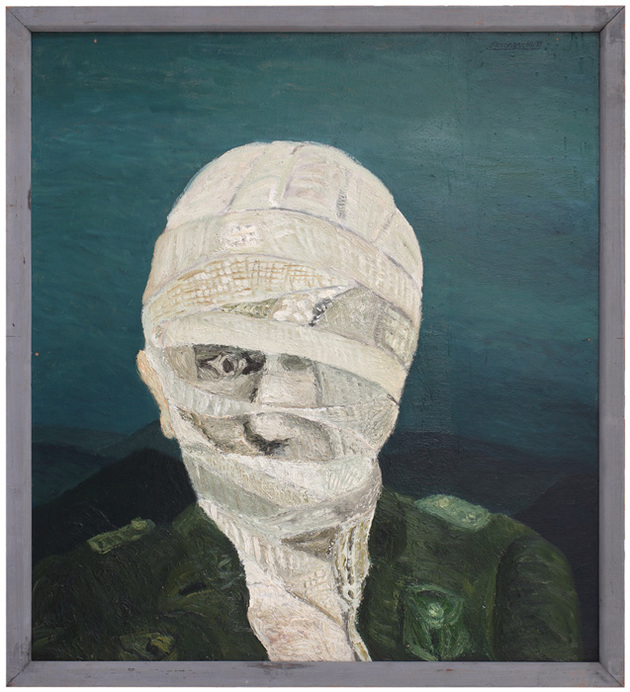

Der Ewige Soldat (1969–70), another painting by Peter Herrmann, is a critique of the militarization of society. Criticism of the military in East Germany was officially forbidden, because the GDR was a member of the Warsaw Treaty Organization, a military and political alliance. Especially around and after 1982, when the United States began stationing Pershing missiles in West Germany and Russians placed SS-20s in the GDR, critique of the military was severely punished. This urgency to critique militarization resonates today, in Poland in particular, where the need to secure the border from threat by a dominant and incalculable Russian superpower has become crucial. With this somewhat parallel situation in mind, there is a renewed sense of urgency to, or at least a timeliness of, this exhibition of images that had all but disappeared.

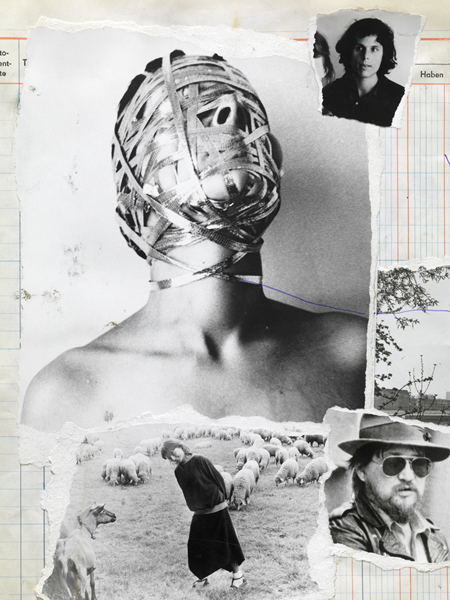

To my mind, there was no clear feminist debate within East Germany. There were, however, a number of artists working in a clear feminist idiom and with clear feminist content, without necessarily realizing that they were participating in a larger international feminist debate; in fact, there was a strong feminist voice within East German underground art. Cornelia Schleime is probably the most well-known of these artists. Gabriela Stötzer is another. One might say her work is reminiscent of works by Ana Mendieta from roughly the same time, however my point is not that there was an original avant-garde in the GDR, but rather to open a door to the past in order to give a glimpse of the context of the time and the experiences of being there then.

One of the issues that we are engaging with in the exhibition is Nelson Goodman’s exploration of the shift from the question “what is art?” to “when is art?”3In the original German: “Im Zweifelsfall ist die wirkliche Frage nicht: ‘Welche Objekte sind (permanent) Kunstwerke?’, sondern: ‘Wann ist ein Objekt ein Kunstwerk?’ – oder kürzer… ‘Wann ist Kunst?’. Meine Antwort lautet: ebenso wie ein Objekt zu gewissen Zeiten und unter gewissen Umständen ein Symbol sein kann – zum Beispiel eine Probe -, so kann es sein, daß ein Objekt zu gewissen Zeiten ein Kunstwerk ist und zu anderen nicht. Tatsächlich wird ein Objekt gerade kraft dessen, daß es in gewisser Weise als Symbol fungiert, und solange es als Symbol fungiert, zum Kunstwerk.” From Nelson Goodman, Weisen der Welterzeugung (Ways of Worldmaking). Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp, 1998 In all of the work in the show, there is a dual voice: one that speaks of melancholy and a sense of entrapment, yet also of freedom of expression. Some of the images are direct and obvious in this regard, while others are more veiled and restrained—and then, of course, there are the abstract motifs, in which only a single gesture describes something.

Especially in the 1980s, debates around the body—the physical body—became very important and, increasingly, so did work that explores distortions of the body, bodily fluids such as blood and excrement, and other such things. The search for order and the retention of it were constitutive principles for the state. The degree to which the models and the desires of the officials to find categories for order and organization verged on the sanitary and the clean, but at the same time one can see the absurdity in them. Some of the motifs of the exhibition are direct and up-front in their expression of fear. In these works, the artists have almost propagated an atmosphere of the apocalypse. And, of course, this is an ever-increasing contrast to the sanitized, blunt optimism of the state’s official art in the style of Socialist Realism.

One must also acknowledge the differences between the decades. In the 1950s, it was possible to go to prison for a joke, which was not the case in the 1980s. The government changed, the role of government officials changed, but nevertheless it was really complicated to bring oppositional perspectives into the official context. The most interesting aspect in all of this is to discuss what “underground” means. We have different descriptions and also words to describe the different artistic positions, because we are speaking about three different generations. The most interesting angle is to follow the personal trajectory of each artist—not to speak about Dresden artists or

Leipzig artists, but to speak about individual artists. That’s why we asked the artists in the show to write about themselves and their positions for the exhibition catalogue. And it is really interesting that half of them wrote that they didn’t feel like dissidents. They have been made dissidents by the outside interpretations of art historians, curators, and critics.

Surveillance played a very important role for artists in the GDR, because the atmosphere of fear meant that every artist had what was, in effect, an inner censor. Self- censorship was common, and it meant that each artist had to define the parameters of artistic freedom for him- or herself. Maybe it is only today, from a retrospective point of view, that we can see how self-censorship translates into categories such as dissident, nonconformist, underground, and so on. Some artists don’t want to be seen as political, because they do not want their work to be seen as propaganda; although it is completely dissident, they want it to be valued for its universal qualities. Other artists have, retrospectively, accepted the label of dissident. Ultimately, the decision one way or the other is about self-perception.

Two more aspects that we need to address: 1976–77 marks the joining of the Helsinki Final Act, or the Helsinki Accords, an international charter of human rights.4The actual signing was in 1975. Here, Tannert is referencing the repercussions felt in the following years. The GDR is among the signatories, and from the point of signing onward, people were able to request their departure papers. For the first time, there was a legal way to leave the GDR. At the same time, it allowed for a little more freedom within the GDR, and a slightly bigger space for expression. Paradoxically, while some people left, those who stayed experienced more freedom of expression.

I’ve spoken about expressionism in regards to figuration, or depiction, but there are also abstract examples of expressionist tendencies, such as Bernd Hahn’s Ohne Titel (1989). The argument could be made that this painting looks like something by Cy Twombly, but again, I’m just opening the door and not necessarily arguing for or against what is inside. I am not the defender of its contents, but rather the messenger.

There are a few unique positions. One is Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, an artist who is now more than eighty years old and has employed only a typewriter to make her visual poems. Her work is an idiosyncratic cross between Letterist and Constructivist positions and it is understood to be political because it always contains language.

In my experience, one of the paradoxes is that 99 percent of Western art historians, including West German art historians, find the official art of the GDR to be much more interesting because it is so contorted and subsumed within the ideological Socialist Realist paradigm. To them, that is a much more compelling case to study than the dissident art, which looks like Western art, but is belated in relation to it. Of course, that is a slap in the face to the artists who were trying to create something different at a time of conformity. So one has to see Voices of Dissent within this tension. We understand the exhibition, twenty-five years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, also to be a belated recognition of or a gesture of appreciation toward these artists who were working under those conditions.

- 1More information can be found on the exhibition’s website. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue with contributions from Tannert, Blume, and many others.

- 2This lecture was delivered more than a month before the exhibition opening.

- 3In the original German: “Im Zweifelsfall ist die wirkliche Frage nicht: ‘Welche Objekte sind (permanent) Kunstwerke?’, sondern: ‘Wann ist ein Objekt ein Kunstwerk?’ – oder kürzer… ‘Wann ist Kunst?’. Meine Antwort lautet: ebenso wie ein Objekt zu gewissen Zeiten und unter gewissen Umständen ein Symbol sein kann – zum Beispiel eine Probe -, so kann es sein, daß ein Objekt zu gewissen Zeiten ein Kunstwerk ist und zu anderen nicht. Tatsächlich wird ein Objekt gerade kraft dessen, daß es in gewisser Weise als Symbol fungiert, und solange es als Symbol fungiert, zum Kunstwerk.” From Nelson Goodman, Weisen der Welterzeugung (Ways of Worldmaking). Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp, 1998

- 4The actual signing was in 1975. Here, Tannert is referencing the repercussions felt in the following years.