In June 2018, members of the Central and Eastern European C-MAP group traveled to Germany for the opening of the 10th annual Berlin Biennale, curated by Gabi Ngcobo. Here, the C-MAP group leader, Roxana Marcoci, records her impressions, and offers a comparative perspective with Manifesta 12 in Palermo.

The 10th Berlin Biennale and Manifesta 12—this year’s editions of two European biennials, both of which were founded after 1989 in response to the new social, cultural, and political realities in the aftermath of the Cold War—have quite a lot in common. They are both relatively small, with fewer than fifty artists and art collectives presented at multiple locations across the two cities; each is curated by a team of creative mediators; each attempts to reverse the usual demographics and name staples of global art exhibitions; and their thematics are subtly yet thoroughly politically engaged. Manifesta’s interdisciplinary curatorial team is composed of Dutch journalist and filmmaker Bregtje van der Haak, Spanish architect Andrés Jaque, Sicilian architect Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli, and Swiss contemporary art curator Mirjam Varadinis; and the Berlin Biennial, which is led by South African curator and artist Gabi Ngcobo, includes a curatorial team comprising American-based art historian Nomaduma Rosa Masilela, Ugandian poet and curator Serubiri Moses, Brazilian educator Thiago de Paula Souza, and German writer Yvette Mutumba.

This edition of Manifesta, a nomadic exhibition occurring every two years in a different European city, is titled The Planetary Garden. Cultivating Coexistence. It takes place in Palermo (a city in the heart of the Mediterranean and at the crossroad of three continents) and explores coexistence in the natural ecosystem as well as in a world moved by invisible transnational networks of private interests. Tapping on its own multilayer history of continuous migration—from the ancient Greeks, the Arabs, and the Normans to recent arrivals from North Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East—Palermo functions like a “laboratory of diversity,” manifest in the expanded geography of movements and in the roster of artists coming from Africa, Europe, the Americas, and Asia. In comparison to the broadly global scope of Manifesta, the Berlin Biennale offers a more salient, localized representation of artists from Africa, or of African descent living in different parts of the world, many of whom have also taken up residency in countries including South Africa, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, India, Namibia, and the Netherlands, thus reconfiguring a history of repressed aesthetic and political vocabularies. Titled We Don’t Need Another Hero, from Tina Turner’s 1985 eponymous song, the Berlin Biennale proposes (like the song) to reject the desire for a savior in favor of “a plan for how to face a collective madness,” in the face of how to confront international shifts in politics and the rise of new historical figures.

Unfolding across three principal venues in Berlin—the Akademie der Künste (ADK), KW Institute for Contemporary Art (KW), and Zentrum für Kunst und Urbanistik (ZK/U)—some of the most critically engaged projects cut across political and philosophical narratives. The South African artist Dineo Seshee Bopape, for instance, presents a multi-part installation in the largest space at KW with smashed bricks suggesting ruins in different stages of decay, enveloped in an eerie strata of orange light, and footage from one of Nina Simone’s 1976 concerts—an exploration into mental madness that recalls Frantz Fanon’s idea of the intersections between displacement, madness, racism, and the colony. Bopape also has a new, poignantly stylized video work that, during my visit, was screened at ZK/U on the opening two days. Drawing on the 2005–6 trial of former South African president Jacob Zuma for the rape of Fezekile Ntsukela Kuzwayo, this video addresses the pervasive epidemic of sexual violence against the black female body. Other artists examining the female condition focus on the context of frictional dynamics between the individual and the nuclear family. In a group of photographs titled Frowst and a 16-mm film installation at KW, the Polish artist Joanna Piotrowska (whose work is also currently on view at MoMA in the exhibition Being: New Photography 2018) taps the Family Constellation therapy method developed by German psychotherapist Bert Hellinger to build a lexicon of body poses among family members that suggests that the collective is at once hostile and a source of safety. Similarly exploring the relationship between the individual and the social body, the paintings of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye on view at ADK include a majestic polyptych A File for a Martyr to a Cause. The work centers on the pensive gaze of four female figures, each with her arms crossed above her head in a gesture that reinterprets a motif in the history of modern art and that taps the uncharted territory of black selfhood.

As in the case of the Berlin Biennale, the artistic projects at Manifesta are spread across the city of Palermo, and while the famous Teatro Garibaldi, a large space situated at the center of La Kalsa, Palermo’s medieval Arab district, functions as the exhibition’s nexus, the venues with the highest concentration of works are the Orto Botanico (Botanical Garden), Palazzo Butera, Palazzo Ajutamicristo, and Palazzo Forcella de Seta. If the Orto Botanico venue comes closest to the biennial’s theme of a planetary garden, with a surprising work by Chinese artist Zheng Bo that explores the potential of eco-queer (the video installed outdoors among bamboo trees shows seven young men walking into a forest in Taiwan and engaging in intimate contact with ferns), it is the Palazzo Ajutamicristo that presents the strongest group of installations. Among them is Lebanese artist Rayyane Tabet’s sculptural work Steel Rings, a sized-down replica of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline that examines the rise and fall of an American venture structure with a length of 1213 km through which oil was transported overland from Saudi Arabia to Lebanon from 1950 to 1983; Filippo Minelli’s Across the Borders, a colorful installation of thirty flags commissioned to individuals living in nations linked by migration policies; Tania Bruguera’s article 11, as much a political as a conceptual document piece about the activist work done in Sicily against the US Mobile User Objective System (MUOS), a harmful global cellular service provider that supports war from a distance; and Trevor Paglen’s It Began as a Military Experiment, a collection of photographic portraits made through an algorithm that identifies key points on a person’s face, thus assisting ethnic and racial profiling. Last year, MoMA acquired this project by Paglen, one of the first photographic works made not for human eyes but for machines, for its permanent collection.

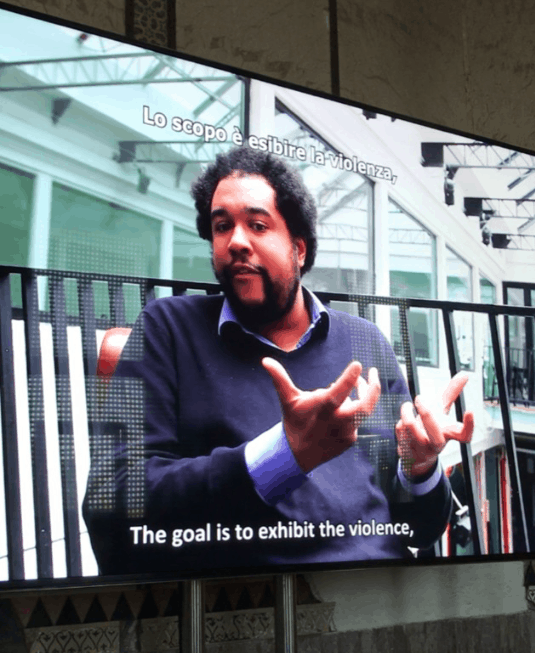

Finally, at Palazzo Forcella de Seta, Kader Attia’s video installation, The Body’s Legacies: The Post-Colonial Body, takes the current refugee crisis as its subject, reflecting on the repressed human rights during the postcolonial period through interviews with four descendants of colonized people or slaves. The narration focuses on a particular event that occurred in Paris in 2017 when a young man Théo Luhaka was beaten and raped with a truncheon by the policemen arresting him. An equally compelling representation of racism and violence against refugees is offered in Mario Pfeifer’s two-channel video installation Again, which, on view at the Berlin Biennale, revisits a 2016 case involving four men on trial for beating an Iraqi asylum seeker with mental health problems and epilepsy, who they alleged was threatening a supermarket cashier.

The two biennials discussed offer effective counter-narratives to the art histories and politics of Western hegemonic nation-states, setting out to prevent indifference toward the violence that is daily perpetuated around the world, and bring to visibility urgent concerns that impact our culture and societies about migration and climate change, violence against minorities, and human rights. Many of these artists’ projects are inspiring in terms of their sustained discourses around civic agency, and reflect some of the ideas that curators at MoMA have been facing in their own research conducted through the C-MAP initiatives, such as the intent to set up complementary, even counter-narratives of pre-colonial and socialist traditions to Western cultural narratives.