Originally a concept that signifies manuscripts in which new layers of writing have been added atop of an effaced original writing, of which traces remain, the palimpsest has evolved into a methodology through which one critically examines a historical phenomenon as embedded in the cycle of inscription, erasure, and re-inscription. This destabilizing yet generative process closely aligns with Michel Foucault’s concept of genealogy, which proposes a refiguration of history and its writing from a linear evolution concerned with utility to a “field of entangled and confused parchments” that operates “on documents that have been scratched over and recopied many times.”1Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. and trans. Donald F. Bourchard (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 139. At its core, genealogy—and the palimpsest—resists what Foucault terms “monotonous finality”: as one attempts to tease apart and decipher the stratified layers of material on the surface, one soon realizes the Sisyphean nature of the task. Overlaid like membranes of semantics and lexicons, these textual veneers refuse a precise deduction, requiring a more holistic understanding, one grounded in their superimposition.

I employ the palimpsest as a methodology to reassess the material ethos of Vietnamese lacquer and its place in prominent canons in Vietnam’s art history, thus opening opportunities for its rewriting. Lacquer refers to the resin extracted from the sơn tree.2Rhus succedaneum, wax tree, or sơn ta is a species found in Phú Thọ and neighboring provinces in North Vietnam. Its resin is the main ingredient in lacquer paint, which is used in both artisanal lacquer and lacquer painting in Vietnam. It is a transparent liquid that alchemically turns varying shades of dark brown and black upon contact with heat and metal. While traditionally applied as a crude varnish to preserve daily objects, in the early 20th century, the first batches of Vietnamese artists trained at L’École des beaux-arts de l’Indochine subsequently transformed it into medium for painting, whereupon coat upon coat of lacquer paint and other materials (vermilion paint, black lacquer, silver and gold leaf, and even eggshell) are applied on top of one another to a wooden base.

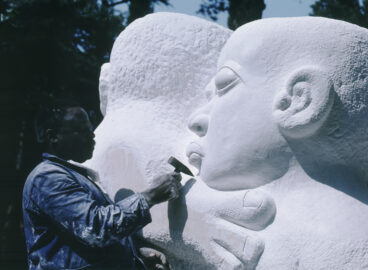

After an extensive amount of time—as lacquer needs humidity to dry and patience to settle—the artist applies a final layer of lacquer paint over the composite block, before sanding away its surface to reveal the materials hidden underneath, a process that balances skillful composition, astute memorization, and pure chance. The act of sanding the surface, akin to the chemical interference that causes textual traces on the palimpsest to reemerge, likewise facilitates a reappearance of previously hidden fragments, thus creating an illusion of depth, which Vietnamese lacquer painter Nguyễn Gia Trí (1908–1993) aptly described “can be felt more accurately with our hands and not our eyes.”3Nguyễn Xuân Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí – Sáng tạo (Ho Chi Minh City: Art & Culture Publisher, 2018), 59. All translations mine unless otherwise noted.

As I compare lacquer with palimpsest, I begin noticing similarities between these two tropes: (1) The creation processes of lacquer and palimpsests mirror one another in that both involve inscription/layering, erasure/sanding, and reinscription/reapplying; (2) While giving an illusion of depth, both objects in fact function at an “utterly flat” surface level.4Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 38. As palimpsest scholar Sarah Dillon has eloquently expressed, the surface structure of the palimpsest can be described as “involuted.” “Involute” is 19th-century literary critic Thomas De Quincey’s term for the way in which “our deepest thoughts and feelings pass to us through perplexed combinations of concrete objects . . . in compound experiences incapable of being disentangled.”5Sarah Dillon, The Palimpsest: Literature, Criticism, Theory (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 104. The palimpsest and lacquer diverge in their surface: while palimpsests present an involuted sense of incongruity—perceived through a spontaneous layering of texts, lacquer orients its surface toward a subtle harmony, as the mutually complementary materials—interspersed between paint laminae and selectively revealed through sanding—assemble into a painterly composition.

This essay is not purely concerned with the history of lacquer painting, or at least with the dominant, normative, and nationalistic version that lauds it as a form of untouchable national art, where any debate or aesthetic or philosophical reexamination of which is deemed uninvited, or treasonous. Instead, I want to experiment with a form of art writing that is palimpsestuous in that it does not adhere to a chronological development of lacquer as surmised in the previous paragraph but rather hinges upon different modes of artists’ in-depth engagement with the aesthetics and process of lacquer as well as the moments in which these modes inform, inter-refer, and inspire one another. Alternating three distinct voices—those of late, renowned lacquer pioneer Nguyễn Gia Trí (through a collection of his transcribed and translated utterances), contemporary artist Trương Công Tùng (born 1986; through his moving-image works), and my own—I aim to position lacquer’s history at the interstices of layers of surface in both text and screen. Trí’s words, Tùng’s video, and my own analysis are then viewed as conceptual inlays that add a performative operation of lacquer, one functioning as an elucidating yet eroding kaleidoscope through which one might view the ever-shifting structures of the two works. In turn, these operations call out ontological challenges that will further consolidate the paradigm of a lacquer metaphor. This constitutes a lacqueresque method.

Lacquer painting requires one to explore its rhythm. Each material has its own unique life. The flow of lacquer is slow, so we can observe its life with ease.6Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 60.

Nguyễn Gia Trí has long been hailed as a pioneer in Vietnamese modern art history, credited with liberating lacquer from its decorative function and elevating it to a medium capable of conveying emotions and abstract thought. His experimentation with abstract composition and unconventional materials, such as eggshell, revolutionized lacquer painting. This shift was comparable to 15th-century Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck’s groundbreaking innovations in underpainting and drying oil medium in oil painting, according to researcher Quang Việt.7Quang Việt, Vietnamese Lacquer Painting (Hanoi: Fine Arts Publisher, 2014), 176. For Trí, in contrast with oil painting, which finishes at the topmost layer, lacquer painting ends at the bottommost layer, an inward journey that searches for sublime truth in the dark depths of enmeshed material vestiges. As Trí notes, “To begin with lacquer painting is to engage with the abstract, as lacquer does not merely reflect reality. A lacquer painter looks into the essence of things, not their outer appearance.”8Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 31.

Trương Công Tùng (TCT): Lacquer is both tangible and elusive; it can be felt and expressed through other mediums such as video or sculptural installation. . . . My practice has always centered on erasing preconceived notions of time and space, which are embedded in presumably concrete materials. . . . Lacquer’s emergence through corrosion allows me not only to dissolve these notions, but also to remain at the contingent point between visible and indivisible, between near and far.9Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 7 March 2023.

Letting go, of the things we see not.10Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 77.

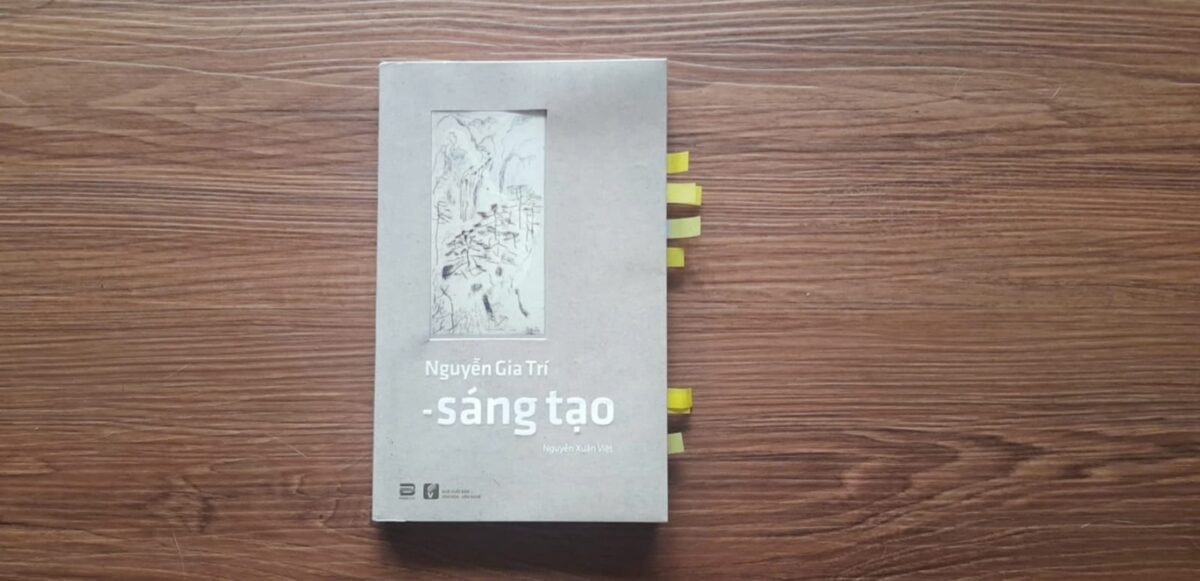

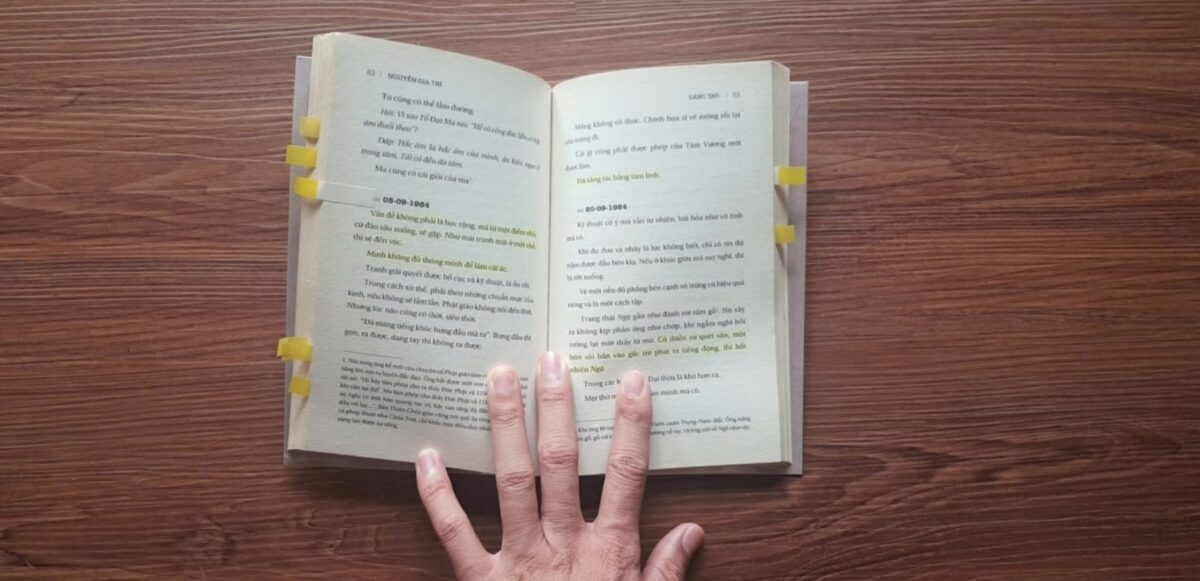

Not much has been known about Trí’s textual ponderance on lacquer, even though art historian Phoebe Scott has remarked that he was connected to Hanoi’s literary intelligentsia through his illustrations and satirical cartoons for modernizing periodicals such as Phong Hoá (Mores) or Ngày Nay (Nowadays).11Phoebe Scott, Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting, exh. cat. (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 6. It was not until 2018, however, that Nguyễn Xuân Việt, one of Trí’s students, published a collection of his teacher’s aphorisms titled Nguyễn Gia Trí – Sáng tạo (Nguyễn Gia Trí – Creativity), in which he encoded Trí’s musings on art, life, and lacquer.

Spanning a variety of topics on lacquer (materials, technique, process, aesthetics, creative philosophy), the book’s structure is arguably lacqueresque, with Trí’s sayings layered atop one another and subtly referencing one another in their shared textual materiality. Throughout the text, we encounter Trí’s interspersed descriptions of lacquer’s flatness (“Lacquer’s flat surface is in fact kinetic.”12Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 80.), its foliated materials (“The vermilion paint inundated the cracks between eggshell pieces, akin to water flooding into canals, everywhere is the same.”13Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 74.), and his technical reflections (“A scratch on the surface / will disappear if you view the painting from different angles. The more you try to polish, the clearer the scratch will show.”14Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 49.). These descriptions perform a chaotic dance with more philosophical ruminations like “The artist must exist inside and outside of the painting, in between each egg shell’s crack”15Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 77. or personal confessions such as “I have been making lacquer painting since its inception, so I am as old as lacquer; my existence is intertwined with it, such as a fish to water, / so I am no longer aware of my existence.”16Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 84.

Trí’s lacquer utterances thus figure lacquer as a composite object composed of abstract and interlayered texts. In addition, lacquer’s ontological operation can be observed through the intertextual relationship between Trí’s lacquer utterances and Việt’s transcriptions of them. Two layers seem to function in parallel here, colliding and colluding with one another, as Viet’s transcription partially concretizes Trí’s lacquer philosophy into a historiography based on the latter’s stream of thoughts. This approach facilitates an intertextual emergence whereby the student’s text-based recording manifests one of many potentials through which his teacher’s words can be accessed and reinterpreted.

This gesture of textually engaging with lacquer and Việt’s intertextual engagement with Trí’s words conjures a personal interception in the national historicization of lacquer in Vietnamese art history—not to interrogate lacquer’s position, but rather to unveil another layer, albeit one overlaid with a more opaque and poetic veneer that suggests a different way of interpreting the history of lacquer.

Out of opacity is born translucence.17Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 47.

TCT: My lacquer practice is a way for me to recognize that I exist, in between the temporal flows of past and future. My body becomes a transitional point, through which images of different time lines pass through and emerge transformed. So, lacquer to me, is a path.18Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16 April 2024.

A lacquer painting’s ending is in the final blink of an eye.19Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 51.

Trương Công Tùng’s works desist from transparent finality. His body of mixed-media works cultivates nonlinearity across different sites. This forms a synergic ecosystem that can be activated against the monotonous view of history as he contemplates the atmosphere enshrouding a speck of soil or peers into the interstices of pixels. His aesthetic is one of lacqueresque superimposition and dissolution hinged upon the metaphorical tendon that links fragmented layers of memories of a landscape, a person, an object.

Trained in lacquer painting at the University of Fine Arts in Ho Chi Minh City, Tùng shared that he was instinctively drawn to lacquer, particularly its simultaneous process of layering and sanding that allowed him to fluctuate between memories of a figure or landscape, between serendipitous revelation and sublime concealment, and to experiment with deconstructing and reconfiguring materials that he foraged from his homeland in Central Highlands and other physical and virtual realms.20Central Highlands (Tây Nguyên), a region in Vietnam that borders southern Laos and northeastern Cambodia, is made up of a series of contiguous plateaus. Home to almost twenty different ethnicities and unique biodiversity zones, this region has undergone many changes throughout history, as its indigenous populations met foreign forces. One of the major shifts in the region’s demographics and cultural fabric was the establishment of economic zones by the Communist government after 1975, which saw the settlement of Viet lowlanders across the Highlands and led not only to continuous ethnic tensions but also unexpected syncretism. Tùng was born into a family of lowlanders who migrated to Central Highlands in the 1980s.

Ultimately, the quantum generated from Tùng’s subtle traverse of layers of his subjects, of lucidity and nebulousness, creates moments of time-space rupture within his works, particularly within his moving images. After foraging visual scraps and recording sound bites from both the natural realm and the Internet’s virtual sphere, Tùng superimposes these images, creating an illusion of depth that comes from visual layering akin to the surface-level effect achieved in lacquer painting. The images appear to commingle and yet obstruct one another: As viewers try to concentrate on a single object, its shadow clandestinely faints, its space corrosively usurped and its time disrupted by another phantom. Tùng’s lacqueresque process of layering and sanding disrupts the spatiotemporal sense surrounding the objects and people within his moving images.

In lacquer, unlike with other mediums, one can find the maximum in the minimum, and vice versa.21Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 138.

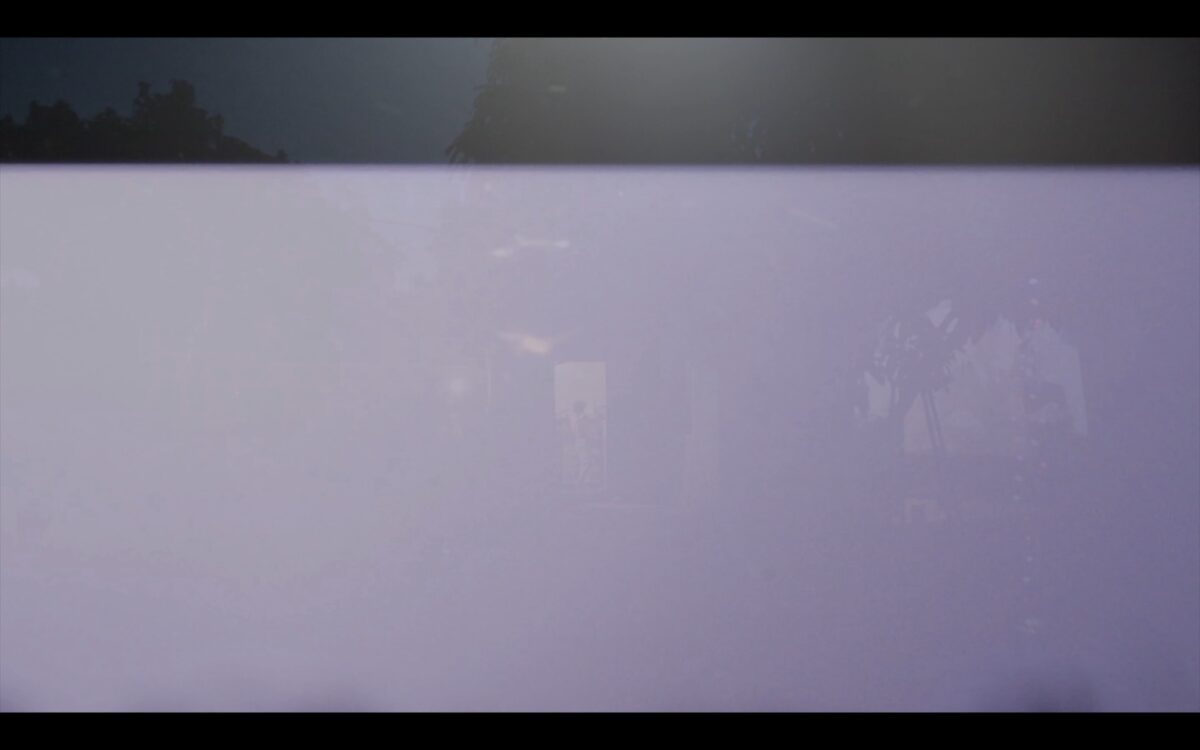

Manifest across four channels, the homeland in Across the Forest (2014 – present) foils reification. Elements that constitute its body blur, sway, and disintegrate; gloved hands pull plastic threads from the soil, fragments of corrugated iron flutter like flags in the wind, a forlorn cocoon is suspended in midair, the silhouette of a figure wears a shirt donned with fairy lights. These vestiges further recede into the depth of the screen as they are superimposed with layers of scenes featuring a cavorting swarm of winged insects under a hazy light. Not only do these illusory layers render the video’s surface more visually abstruse by creating a false impression of depth, they also eradicate any sense of temporal or spatial markings of the landscape, collapsing the demarcations between realms. This effect delineates a lacqueresque intervention into the landscape of the Central Highlands that resists conventionalization and exotification and is, instead, vested in private dreams and personal memories.

TCT: Landscape in Across the Forest exists as layers . . . one layer of day and the other of night . . . the time and space within day and night are also superimposed, so that they simultaneously appear . . . one exists because the other exists . . . sometimes the brightness of day inundates a scene, others are dimmed by the dark of night . . . still, they remain independent . . . a mutual symbiosis.22Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16 April 2024.

An instance of spatial illusion occurs in a scene shot inside Tùng’s family home in the Central Highlands, where his father and nephew are watching an advertisement on an obscured TV screen. Through the open door behind them, we can see yet another screen-layer showing the same advertisement, which Tùng has inlaid to create a visual loop that exponentially extends the space within his house. These seemingly detached layers of screen-within-screen coexist on the surface of the video work, alluding to Tùng’s lacqueresque process of handling space.

TCT: What fascinates me about lacquer . . . is its ability to scrub away the boundaries between spaces, or concepts of space . . . between objects and materials as well . . . to render something not just as it is but beyond . . . each layer of paint is a different space with specifically tailored images . . . yet, when you sand the surface, it erases the distance between these spatial layers, collapsing them.23Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 7 March 2023.

There exists no sense of territory within lacquer. A lacquer artist’s job is to dissolve boundaries and borders.24Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 95.

A propensity for eradication, which stems from Tùng’s muscle memory of sanding the surface of lacquer painting, unfurls in another scene of the artist’s family house. The silhouettes of the house and the trees surrounding it emerge from the video’s opaque background, overlaid with the filament of insect wings. White bands flash across the screen, temporarily wiping out parts of the landscape, like the static and noise that corrode images on an old television screen. As soon as they appear, the ghostly bands dissipate, leaving only faint illusions behind our eyelids. The white bands can be seen as ghostly traces of Tùng’s sanding, disrupting the work’s temporal flow by inserting blank slates into its configurations. Time becomes oblique due to this lacqueresque intervention; an entity that symbolizes inevitable erosion is now subject to abrasion.

TCT: The moment your hand touches the surface, in preparation for sanding, it already signifies a shift . . . each touch will change time . . . without your physical interference, the past and present time remain intact . . . yet, the moment you begin to sand away, they began colluding with one another, coexisting, which brings about a change in future time as well . . . you remember the layer that you sand, yet you also forget it . . . you have to consider both sides of your hand, what it is capable of.25Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 7 March 2023.

An ant, crawling on the ground, understands space differently than a mosquito flying in the air.26Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 116.

TCT: I operate at that point of tugging friction, which I always try to pinpoint while making work, a mnemonic anchor that helps me remember or forget . . . to orient myself toward something new altogether . . . in order to dissolve the lens’s power, I have to incorporate many layers, so as to question the role of my eyes . . . you have to reflect on your way of seeing . . . so each layer in my video is both ancillary to and obstructive toward each other layer, to create moments of tension for self-reflection.27Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16 April 2024.

As time and space distort, the memories and histories of people and communities in Tùng’s videos blur and morph, shifting from one murmuring sound to another dissipating figure. This lacqueresque effect of visual layering and dissolution, coupled with an almost trance-like audioscape, subtly gestures toward an oneiric reconstruction of Tùng’s homeland—allowing not only its residents but also onlookers to participate in its reimagination. The land’s history is thus renegotiated, albeit temporarily, within the scope of the moving image. In the end, lacquer binds Trí’s text and Tùng’s video not only through its fragmentary aesthetic and layered process, but also through the desire for a change in perspective—exemplified in Trí’s caution to stop drawing with your eyes and Tùng’s wish to create moments of tension for self-reflection. Lacquer’s power to disrupt an object or landscape, excoriate its characteristics, and diffract its history harbors immense transformative power to reinvent our perspective, allowing us to see it differently and write about its history differently. By attempting a lacqueresque approach, in which different voices, texts, and ideas are layered, I hope to deliver a performative lacquer-text, in which cohesive thoughts and fragmentary musings construct and construe one another, colliding and colluding as they trace and retrace one another’s step.

- 1Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. and trans. Donald F. Bourchard (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 139.

- 2Rhus succedaneum, wax tree, or sơn ta is a species found in Phú Thọ and neighboring provinces in North Vietnam. Its resin is the main ingredient in lacquer paint, which is used in both artisanal lacquer and lacquer painting in Vietnam.

- 3Nguyễn Xuân Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí – Sáng tạo (Ho Chi Minh City: Art & Culture Publisher, 2018), 59. All translations mine unless otherwise noted.

- 4Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 38.

- 5Sarah Dillon, The Palimpsest: Literature, Criticism, Theory (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 104.

- 6Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 60.

- 7Quang Việt, Vietnamese Lacquer Painting (Hanoi: Fine Arts Publisher, 2014), 176.

- 8Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 31.

- 9Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 7 March 2023.

- 10Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 77.

- 11Phoebe Scott, Radiant Material: A Dialogue in Vietnamese Lacquer Painting, exh. cat. (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), 6.

- 12Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 80.

- 13Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 74.

- 14Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 49.

- 15Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 77.

- 16Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 84.

- 17Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 47.

- 18Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16 April 2024.

- 19Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 51.

- 20Central Highlands (Tây Nguyên), a region in Vietnam that borders southern Laos and northeastern Cambodia, is made up of a series of contiguous plateaus. Home to almost twenty different ethnicities and unique biodiversity zones, this region has undergone many changes throughout history, as its indigenous populations met foreign forces. One of the major shifts in the region’s demographics and cultural fabric was the establishment of economic zones by the Communist government after 1975, which saw the settlement of Viet lowlanders across the Highlands and led not only to continuous ethnic tensions but also unexpected syncretism. Tùng was born into a family of lowlanders who migrated to Central Highlands in the 1980s.

- 21Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 138.

- 22Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16 April 2024.

- 23Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 7 March 2023.

- 24Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 95.

- 25Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 7 March 2023.

- 26Việt, Nguyễn Gia Trí, 116.

- 27Trương Công Tùng in discussion with the author, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 16 April 2024.