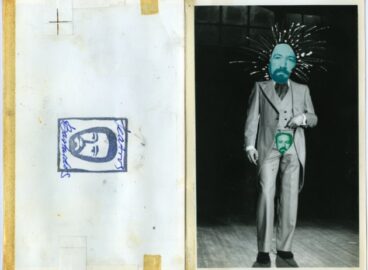

This selection of materials was featured in the exhibition “The Unmaker of Objects”: Edgardo Antonio’s Marginal Media, a display of works from Library Special Collections at the Museum of Modern Art from April 2 to June 30, 2014.

The exhibition celebrates the mail art, visual poetry, performative works, and publications of the Argentine artist Edgardo Antonio Vigo (1928–1997). From his hometown of La Plata, Vigo developed an extensive network of contacts in the Americas and Europe, making the city a hub of the international mail art movement—a loose network of artists who exchanged ideas, art, and poetry through the postal system. From his defiantly local position, Vigo developed an internationalism tempered by a sharp critique of the foreign policy of the United States, from its role in the Vietnam War to its support of authoritarian Latin American governments.

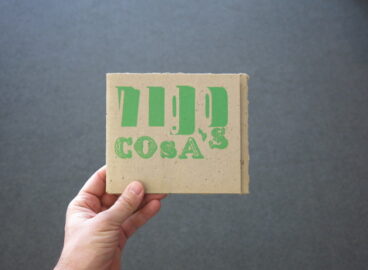

Interested in mass media and alternative channels of communication, Vigo nevertheless maintained an intimate human touch, producing handmade works that he bluntly called cosas, or “things,” to challenge the hierarchies of aesthetic tradition. Consistent with his embrace of mail art, which involves the participation of a recipient, he developed instructions, actions, and visual poems to be carried out or completed by others. He also published magazines and editions that promoted an accessible, democratized art in place of the unique and valuable art object.

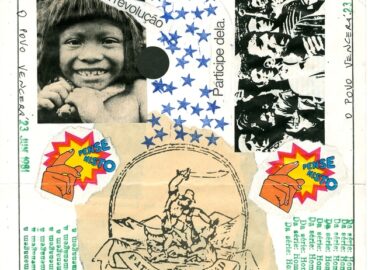

Vigo was active during the period when Argentina was ruled by a military junta, which, in 1976, “disappeared” his son Abel Luis “Palomo”. Vigo and the artist Graciela Gutierréz Marx together adopted the pseudonym G. E. Marx Vigo and campaigned for Palomo’s return; they often stamped the envelopes they sent out through the mail art network with the English phrase “Set Free Palomo.” Despite government censorship, Vigo’s moving letters and graphic works reached artists the world over, testaments to his dedicated ethical commitment.

This selection of works is divided into three sections:

Vigo’s “Things”

Vigo called himself an “unmaker of objects.” Instead, he made cosas (“things”)—works that did not clearly fall within traditional mediums such as painting, sculpture, printmaking. Vigo’s cosas were conceptual in nature and made to be completed by the participant. They ranged from a series of “signalings” of everyday scenes or objects that viewers were invited to regard aesthetically, and actions and poetry “to be created” by the participant. The works were intended to activate the participant’s perception by engaging them in unfamiliar activities.

Diagonal Cero Magazine (1962–1969) Vigo began publishing his magazine Diagonal Cero in 1962. It was named after a street in his hometown La Plata, known as “the city of diagonals” because of its many diagonally-oriented streets, and the name refers to an imaginary Avenue Zero. With the exception of being unbound, it was initially a fairly conventional magazine designed to circulate new poetry. As time went on, though, Diagonal Cero began to play more and more with what a publication could be, developing a strong editorial and graphical style. Of the run of twenty-eight issues, number 25 is missing because it was “dedicated to nothingness.” Emptiness is also addressed in the “Cavity Manifesto” in issue 28, as well as by repeated perforations and holes. In 1969, Vigo ceased publishing the magazine with a characteristic wordplay emblazoned on the inner sleeve: ‘No VA MÁS’ (All bets ARE OFF), both a statement to indicate the termination of the magazine and a denunciation of political conditions in Argentina.

Hexágono ’71 (1971–1975)

Hexágono ’71 was distributed as an envelope containing illustrations, visual poems, works “to be created,” essays, drawings, stories, telegrams, and calls for works by both international and local authors. Hexágono ’71 contained no editorial commentary, page numbers, or editorial credits. Furthermore, the issues were systematised by a lettering system rather than the customary numbers: a, ab, ac, bc, bd, be, cd, ce, cf, de, df, dg and e. Vigo referred to himself as the editor in-responsible (“non-responsible editor”) of the magazine and said, “There are no fixed collaborators, the issue takes shape as the works come in.” The magazine grew more and more international from 1971 to 1975, uniting artists from Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Brazil, the United States, France, Italy and the UK. Hexágono ’71 was inaugurated during the dictatorship of 1966–73. Vigo wished to “share the necessity of breaking the dangerous suffocation that hovers over the universal creative-investigator’s free expression.”

A selection of materials from the exhibition, Edgardo Antonio Vigo: The Unmaker of Objects