In this essay, Michaëla de Lacaze engages in a close reading of Happy Bicentennial (1976), one of the most radical pieces of mail art created by artist and poet Clemente Padín during the Uruguayan authoritarian regime of the 1970s. Analyzing the often overlooked role of ambiguity and polysemy in this work, de Lacaze examines how Padín’s militant mail art practice complicates historically overdetermined framings of Latin American conceptual art and how it differs from North American mail art practices.

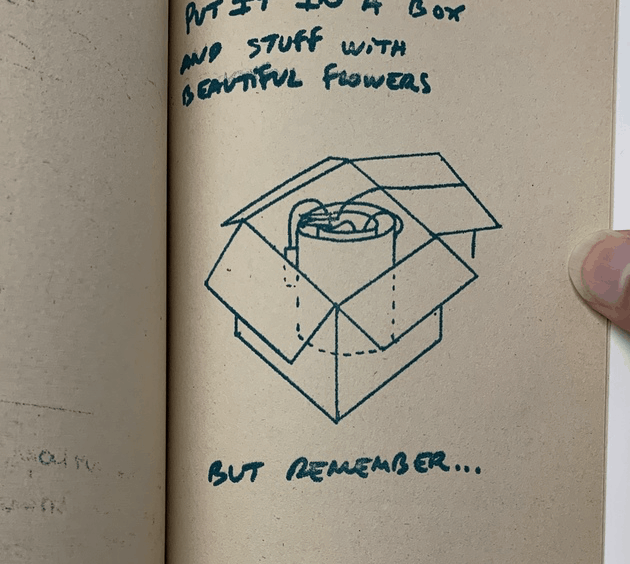

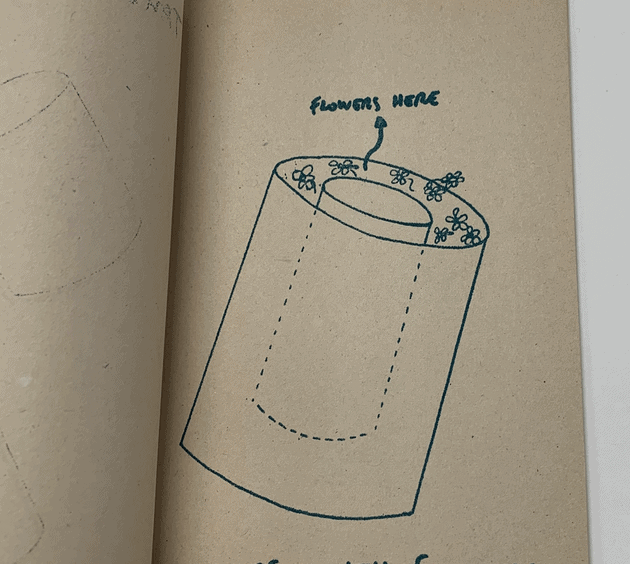

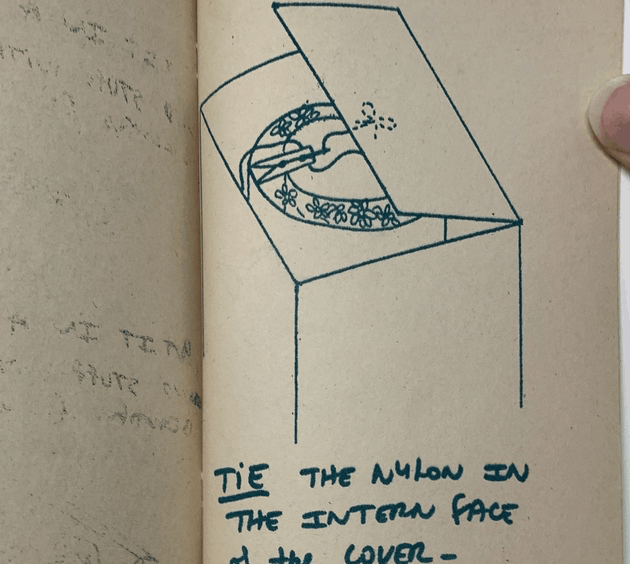

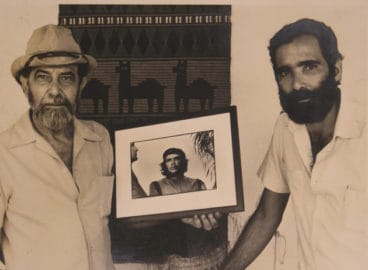

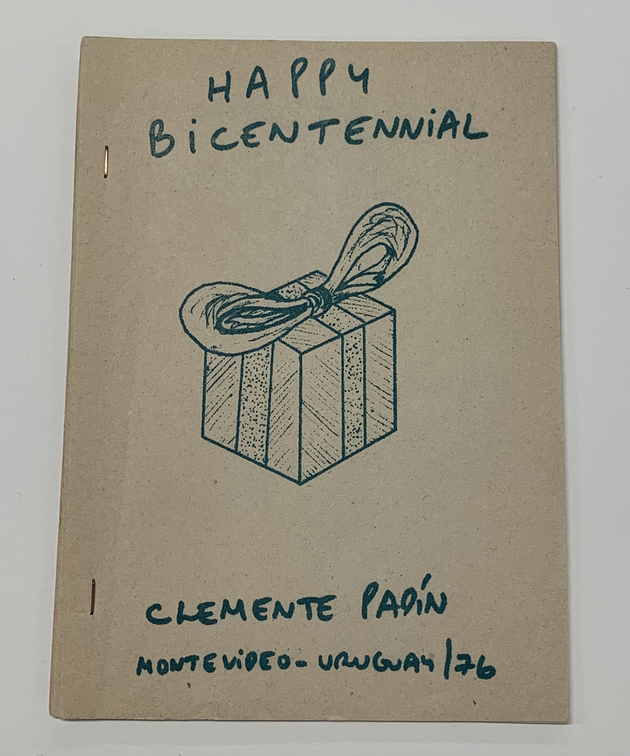

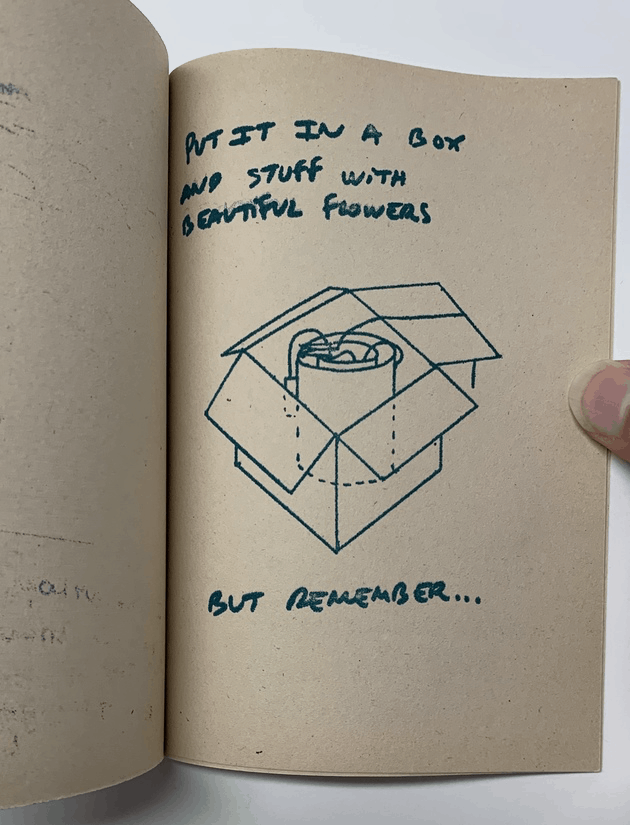

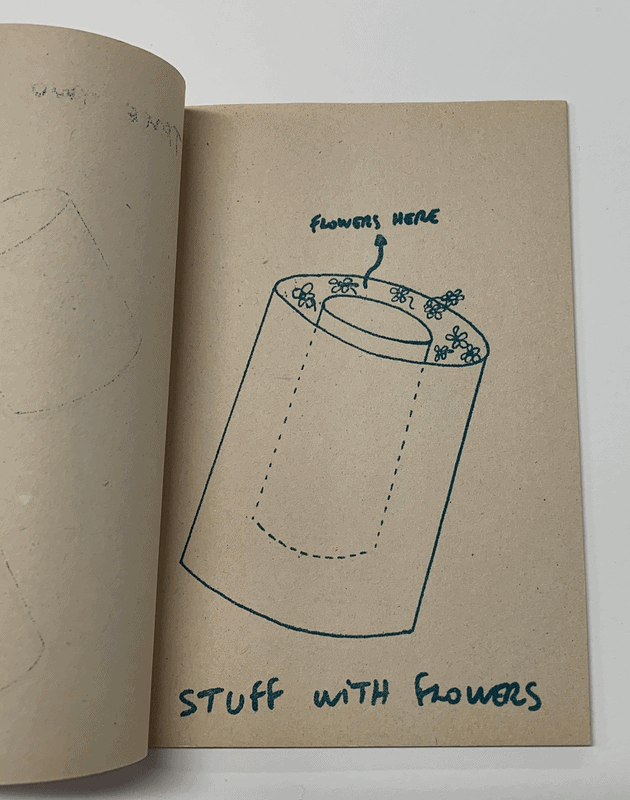

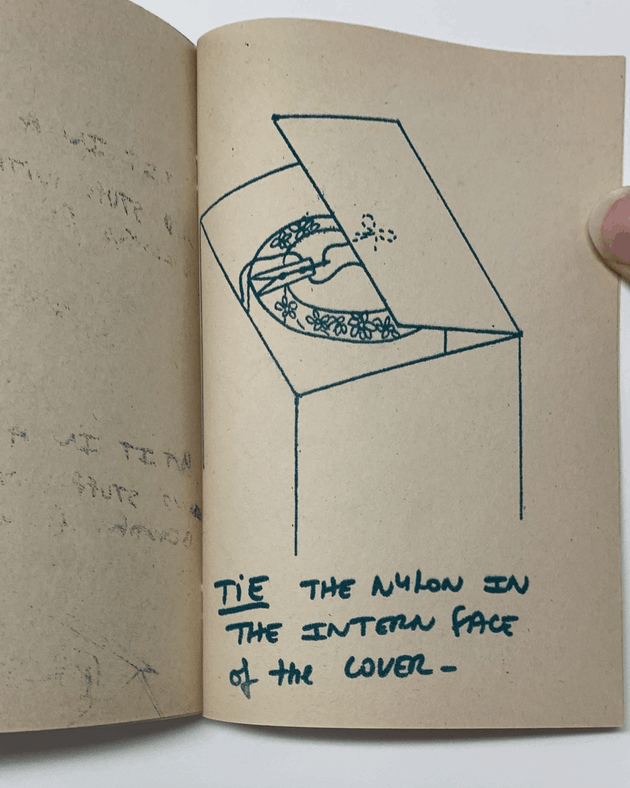

By the mid-1970s, the military dictatorship of Uruguay had pushed the poet and mail artist Clemente Padín to live clandestinely within his own country.1Soon after his election, in 1972, President Juan María Bordaberry suspended the constitution and began ceding power to the armed forces. In June 1973, the military consolidated its control over the nation through a coup in which Bordaberry willfully participated, becoming a puppet of the military until he was fully ousted in 1976. The authoritarian regime would remain in power until 1985. During the tumultuous mid-1970s, Padín was receiving and sending mail only through third parties rather than through the post. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. To avoid censorship of his art and persecution, he asked his friend in Amsterdam, the Mexican artist Ulises Carrión, to publish and distribute Happy Bicentennial, arguably one of Padín’s most politically incendiary pieces of mail art. Carrión, who ran Daylight Press,2In the mid-1970s, Ulises Carrión began Daylight Press, an editorial name and address in Amsterdam for artists to use in the creation of their own publications. Michael Gibbs, Eduard Bal, John M. Belis, and Gerrit Jan de Rook are some of the artists who made use of this press. printed multiple copies of this booklet, which he mailed to the United States in 1976.3The work entered the Franklin Furnace Archive in 1982, but its exact whereabouts between this moment and its publication in 1976 remains unclear. Little is known of the addressees chosen by Carrión, but their response to Happy Bicentennial is imaginable. After tearing open an envelope, the work’s first North American recipients might have been amused to discover yet another mysterious package—the surprise birthday present depicted on the booklet’s cover. Festooned with a ludicrously large bow, the gift beckons to be unwrapped, but the only option is to thumb through its text. With every turn of the page, however, the sanguinity of the work’s title and first illustration shades into something more sinister. In effect a manual, it contains diagrams that give step-by-step instructions on how to build a simple yet functional bomb to be delivered to any office on Wall Street. This was Padín’s sardonic gift to the United States on its 200th anniversary.

“It’s a work born of anger and resentment . . . born in [an] environment of rejection and impotence,” Padín recalls today.4Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. My translation. He conceived it when the dictatorship ordered Uruguayan newspapers to circulate recipes for homemade explosives with the intention of arming the general public against political dissidents.5Padín recalls that El País, the country’s leading newspaper, published these instructions. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, April 1, 2019. Happy Bicentennial appropriates these directives, switching their target to Wall Street. This détournement of state-sponsored violence exposes the true hidden source of the dictatorship’s power: the US banks and corporations, which actively financed Uruguay’s government even after the administration of President Jimmy Carter imposed sanctions in 1977.6Starting in 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s administration imposed diplomatic sanctions on Uruguay in condemnation of the dictatorship’s violation of human rights (by then, torture, disappearances, executions, and unjustified imprisonments were well documented by Amnesty International). However, US banks and corporations continued to do business with the dictatorship, sustaining it through the economic turmoil brought on by its pariah status on the international stage. For more on this, see Isabel Clemente Batalla, “El context político international y la política exterior uruguaya durante la dictadura (1973–1985),” in El negocio del terrorismo de estado: Los cómplices económicos de la dictadura uruguaya, ed. Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky (Montevideo: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2016). Not every US president had opposed the authoritarian regime, however. President Richard Nixon (1969–74) and his successor President Gerald Ford (1974–77) had backed it well into the second half of the 1970s—a position that the administration of President Ronald Reagan resumed in 1981.7Arguing for their inefficacity, Reagan reversed the sanctions of the Carter administration. For more on this topic, see ibid., 66. Consequently, the Uruguayan dictatorship remained pro-American throughout the 1970s, organizing, without any sense of irony, various sycophantic celebrations surrounding the US bicentennial.

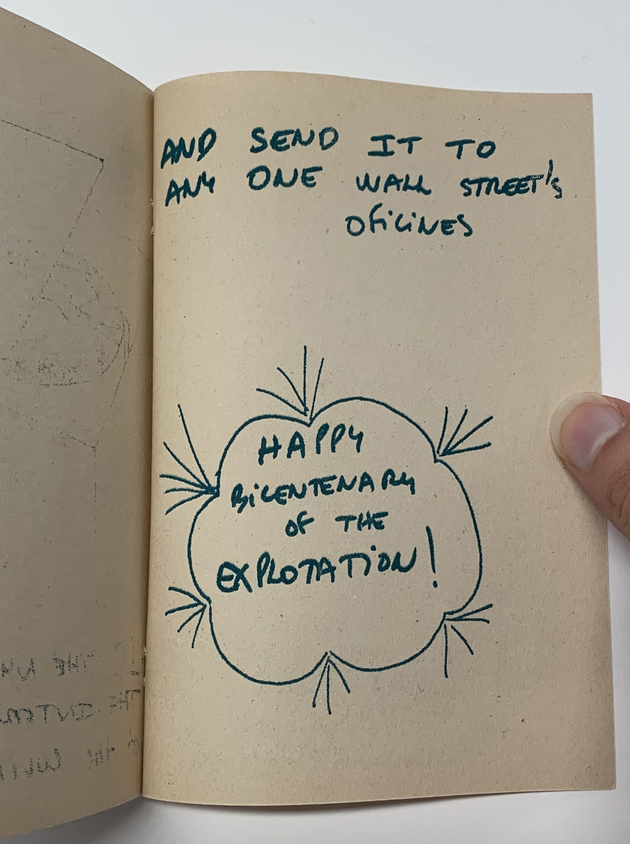

Still piqued today by the hypocrisy of these festivities, Padín recollects, “Not a single voice critically judged those 200 years or what they meant to Uruguay and the rest of Latin America, blood and exploitation.”8Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. My translation. Happy Bicentennial’s final statement, “Happy Bicentenary of the Explotation!” contests the dictatorship’s interpretation of US-Uruguayan relations by linking Wall Street’s support of authoritarianism to a longer US history of capitalist exploitation—the slavery and genocide that the birth of a US democratic republic encoded into law.9By removing an i, Padín creates a pun by fusing the word “exploitation” with “explosion.” This propensity of the United States to undermine its liberal ideals by pursuing the profitable domination of others would also lead to its interventionism in Latin America, as Padín intimates above.10From Panama and Guatemala to Cuba and Chile, the United States has a long history of interventionism in the region.

Operating like a Trojan horse, Happy Bicentennial revives the violent, tactical logic of the then recently defeated Tupamaros, a left-wing Uruguayan guerilla group whose aestheticized political actions, according to the artist and academic Luis Camnitzer, form part of the universe of Latin American conceptualism.11Luis Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 58. To Camnitzer, the Tupamaros “exemplify politics coming as close as possible to the art side of the line” and are the mirror image of projects such as the exhibition Tucumán Arde and, I would argue, Happy Bicentennial, which approach this limit from the side of art. Ibid., 44. The criminal outcome envisaged by Happy Bicentennial would be hard to distinguish from the Tupamaros’s own activities and subterfuges—kidnappings, bombings, and robberies, which are viewed by Camnitzer as forms of spectacular theater or performance oriented toward the media. Ibid., 49. In fact, Camnitzer concludes his chapter on the Tupamaros by citing Padín’s own words: “In a political act we find political elements, and subsequently elements that are social, religious, aesthetic, etc. Art in the street . . . assumes the aesthetic instances of politics and tries to direct them against their creators. . . . Attacking [the apparently evident, normal and natural rules] and formulating one’s own rules means to question the legitimacy of the system.” Ibid., 59. Padín’s booklet thus belongs to a constellation of Latin American conceptual artworks12Latin American artists working in this politicized conceptual mode include Cildo Meireles, Eugenio Dittborn, Luis Camnitzer, Graciela Gutiérrez Marx, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Jac Leirner, Victor Grippo, Gonzalo Díaz, Alfredo Jaar, and the artist collective Tucumán Arde, among others. recognized for their capacity to intervene in politics and radically merge art with life.13“Translating this experience [of authoritarianism] artistically in a significant way could proceed only from giving new sense to the [Latin American] artist’s role as an active intervener in political and ideological structures,” writes Mari Carmen Ramírez with regard to Latin American conceptualism in her seminal essay “Blue Print Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, ed. Waldo Rasmussen. exh. cat (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1993), 158. Yet Padín bristles at the thought of anyone associating his art with Camnitzer’s aesthetic reframing of guerilla activity. “Who can imagine a work of art in which the protagonists, actors, or performers spill their blood and die?” he asks as though Happy Bicentennial did not ostensibly conjure this very outcome. How to make sense of these contradictions? Or of Padín’s ambivalence toward Happy Bicentennial, a work he now “would like to eliminate”?14Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. My translation. Padín today expresses a mixture of remorse and unease regarding his creation of Happy Bicentennial, which he wishes could be “erased.” Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, April 15, 2019. My translation. His trepidation regarding this work stems from his awareness that his call to bomb New York’s financial district resonates differently in a post-9/11 world than it did in the 1970s. Additionally, during his imprisonment by the military dictatorship, Padín was tortured during interrogations specifically on Happy Bicentennial. His interrogators went so far as to threaten to bomb his home and thus kill his wife and child. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 29, 2019. This traumatic experience informs the artist’s current misgivings about this particular work of mail art.

In recent years, the emphasis of art historical discourse on the ideological nature of Latin American conceptualism has often rendered its subtleties and aporias invisible.15For more on this topic, see, for example, Miguel A. López and Josephine Watson, “How Do We Know What Latin American Conceptualism Looks Like?” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 23 (Spring 2010): 5–21. In these sometimes historically overdetermined readings, the notion of Latin American art as staunchly engagé suppresses the uncertainties, mercurial views, and irresolvable dilemmas of artists who sought to ingress a fraught political terrain. Padín, however, speaks lucidly of this thorny process, avowing, “In whatever product of communication [or mail art] that I choose to transmit there are the characteristics of relationships between society and me. Of course, this includes the antagonisms and contradictions that these relationships present.16”Clemente Padín, “The Options of Mail Art,” in Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, ed. Chuck Welsh (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1995), 206. My emphasis. Without defusing the political explosiveness of Happy Bicentennial, it is therefore necessary to tease out the nuances and contradictions belied by its patent partisanship.

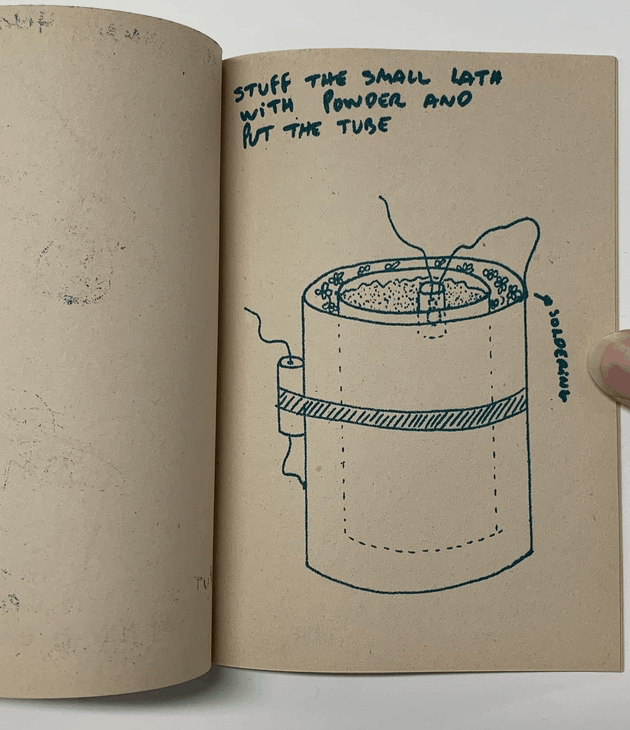

Despite all its overt references to politics, Happy Bicentennial embraces ambiguity to cloud authorial intentions. This, in turn, burdens the reader with a hermeneutic (rather than uniquely moral) dilemma that suspends the work in an ontological limbo and complicates its putative interjection in politics. Happy Bicentennial’s deliberately vague and telegraphic language, for instance, does not specify that the “powder” to be used must be gun powder.17“Stuff the small lath with powder and put the tube,” reads the booklet. The reader is left to deduce this crucial fact—a facile interpretive leap that shifts responsibility away from the artist. Incongruous images amplify the reader’s sense of uncertainty. The bomb is stuffed not with lethal metal shrapnel but rather with delicate, “beautiful flowers,” which render it innocuous, even absurd. The nonsensical juxtaposition of blossoms and bomb also imbues Happy Bicentennial with a Dadaist spirit that reinforces the status of this ostensibly utilitarian object as a work of art not to be taken literally.18Coincidentally, the combination of flowers and bomb is reminiscent of André Breton’s famous description of Frida Kahlo’s art as a “ribbon around a bomb.” André Breton, “Frida Kahlo de Rivera (1938),” in Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2002), 144.

Padín was not always so cautious. Another 1976 version of Happy Bicentennialclearly labels the contents of the bomb as “grape-shot,” a fact which perhaps explains why this version was never circulated by Carrión.19This version of Happy Bicentennial became public much later, in 1984, when reproduced in Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet, eds., Correspondence Art: Source Book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity (San Francisco: Contemporary Arts Press, 1984). Earlier, in 1971, Padín had published in OVUM 10 a germane how-to guide for a Molotov cocktail in which revolutionary mantras and acerbic political commentary take the place of didactic captions. Happy Bicentennial, by contrast, has expunged all explicitly militant puffery and refuses to proselytize. The tone of its final, punning line—“Happy Bicentenary of the Explotation!”—is sarcastic, not earnestly bellicose.

Padín thus blunts the political—indeed, arguably terrorist—intent of his work; it is less a set of persuasive instructions to be executed than a provocative hypothetical confined to the realm of the imaginary (at least thus far). Nevertheless, the booklet causes Uruguay’s reality to erupt into the hic et nunc of its readers. In other words, Happy Bicentennial compels its US audience not to become active guerilla cells but, rather, to inhabit something akin to the predicament of Uruguayans under authoritarianism. Its readers must not only contemplate killing their fellow citizens, as Uruguayans reading the newspaper once had; they are also pushed into an unstable semantic and symbolic territory. Camnitzer reminds us, “The line separating liberating activities from crime, always blurred by changing definitions of legality, was even more confusing under [Uruguay’s] dictatorship.”20Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art, 57. To risk interpreting Happy Bicentennial’s instructions is to get a taste of this confusion—and for good reason. Few things are more anathematic to the artificial consensus and literalist propaganda of authoritarianism than this empathy born of equivocality.

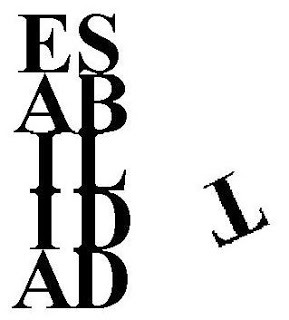

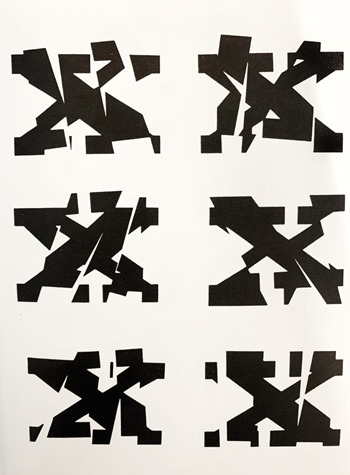

Indubitably, the ambiguity refracting the imperatives of Happy Bicentennial stems in large part from Padín’s visual poetry. “Ambiguity and self-reflexivity are without a doubt the marks of the poetic,” Padín affirms.21Clemente Padín, “Estrictamente Autorreflexivos,” in Clemente Padín: Poesías completas, ed. Carlos Pineda (Mexico City: Ediciones del Lirio, 2013), 317. My translation. Through their unorthodox spatial arrangements and experiments with typography, his self-referential poems activate multiple—often opposite—valences from their words and symbols. Epitomizing Padín’s notion of semantic instability, his visual poem “Oxímoron” (Oxymoron; 1984) stacks the letters of a single word—“stability”—into a precarious tower from which a letter falls out, thus jeopardizing the column of text both structurally and semantically.22“Oxímoron,” Padín explains, “is one of the poems I love the most.” He describes it as “a thing that is and isn’t at the same time.” The poem, written toward the end of the Uruguayan dictatorship, as Padín is keen to point out, alludes to the precariousness of this sociopolitical context. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, June 11, 2019. The poem is also alternatively titled “Estabilidad 1 (Stability 1)” and was published multiple times, most recently, in Patricia Bentancur, ed., Clemente Padín(Montevideo: Banco Central del Uruguay, 2006), 79 and Pineda, Clemente Padín: Poesías completas, 350.

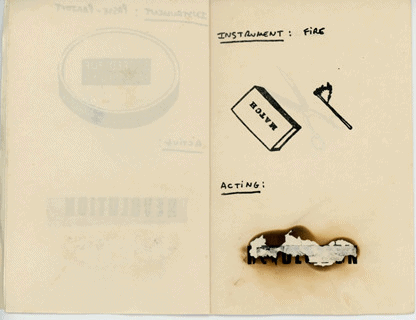

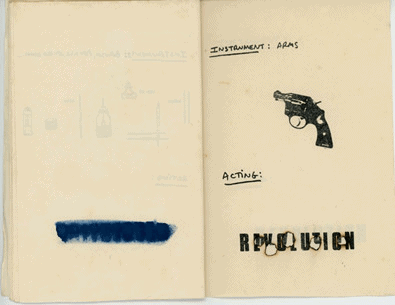

Padín’s other mailed booklets are also open to opposite interpretations. Instrumentos/74 (1974), for example, provides a list of destructive tools to be presumably used in an insurrection, as suggested by the presence of the term “revolution” on each page. Yet Padín immediately puts each mode of attack into practice, illustrating its destructive power by repeatedly blighting this word away. The result is a compendium of wounds, from cuts and burns to gunshots. If this booklet at first seems to incite sedition, its gradual and increasingly ludicrous self-obliteration acts as a deterrent, a warning of the high cost of rebellion. Likewise, its concerted attack on the increasingly illegible word “revolution” seems to wish this concept (or, rather, its painful historical recurrence) out of existence.

The calculated creation of polysemy across visual and linguistic registers is not unique to the mail art of Padín. He also identifies it in the work of Argentine mail artist Edgardo Antonio Vigo, writing “His [Vigo’s] emphasis on the self-referential qualities of a work of art, which not only foster ambiguity (the possibility of extreme polysemy) but also the possibility that it is the spectator who can make the final choice regarding its meaning, encourages him to think of the spectator as a co-author.”23Clemente Padín, “Edgardo Antonio Vigo: A Libertarian Aspiration,” in Clemente Padín, ed. Bentancur, 341. In this essay, Padín links the participatory ambiguity of Vigo’s art to the work of Joseph Kosuth and Marcel Duchamp. The latter artist represents to Padín “the most significant precedent” for mail art. See Clemente Padín, “Arte correo: 50 años desde la óptica latinoamericana,” Arte y Parte, no. 101 (2012): 17. My translation. Though Padín only cites Duchamp’s postcards as an example of mail art avant la lettre, the Uruguayan artist’s interest in Duchamp is also due to the ambiguity produced by the French artist’s myriad double entendres. Unsurprisingly, the title of Padín’s 2003 poetry book, La poesía es la poesía, employs a strategy of nominalism stretching back to Duchamp, as Martín Palacio notes. See Palacio, “La poesía es la poesía,” in Clemente Padín: Poesías completas, 307. These words echo Padín’s own assessment of his poetry, “They are called self-referential or self-reflexive poems . . . for in talking about themselves and in their effect on the signification of the text, they generate ambiguity. . . . [They] open a world of meanings and significations that will give the ‘reader’ the free option to interpret the text.”24Clemente Padín, “Estrictamente Autorreflexivos” in ibid., 317. My translation.

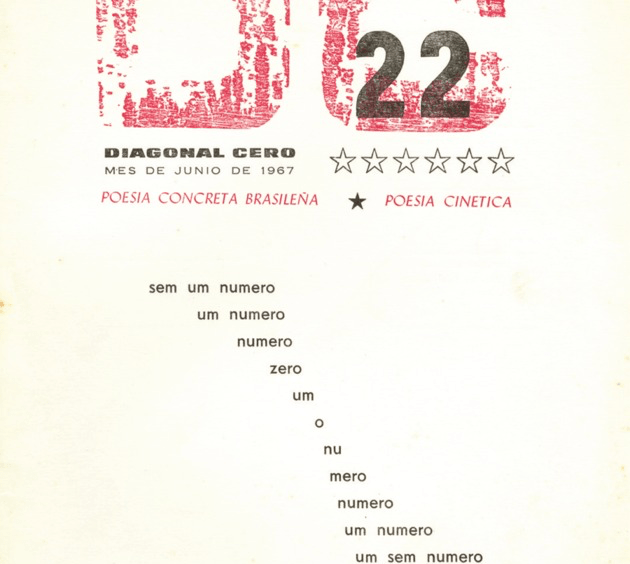

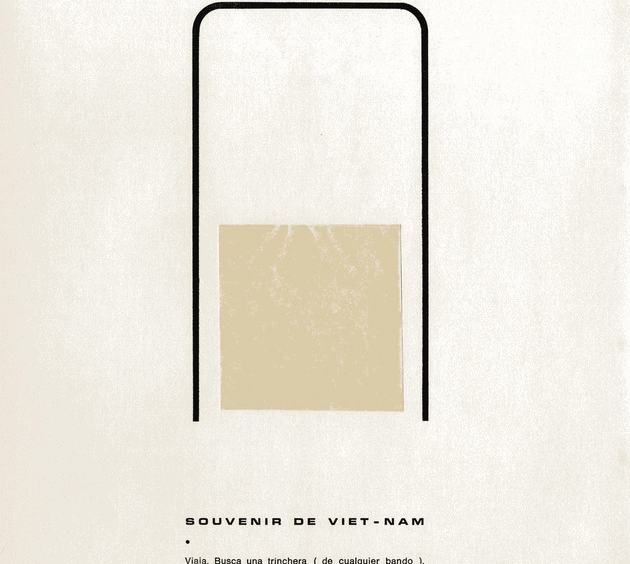

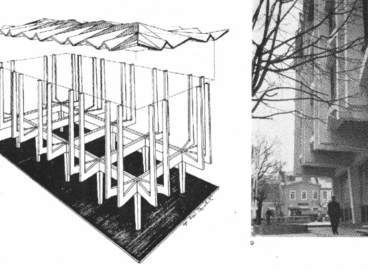

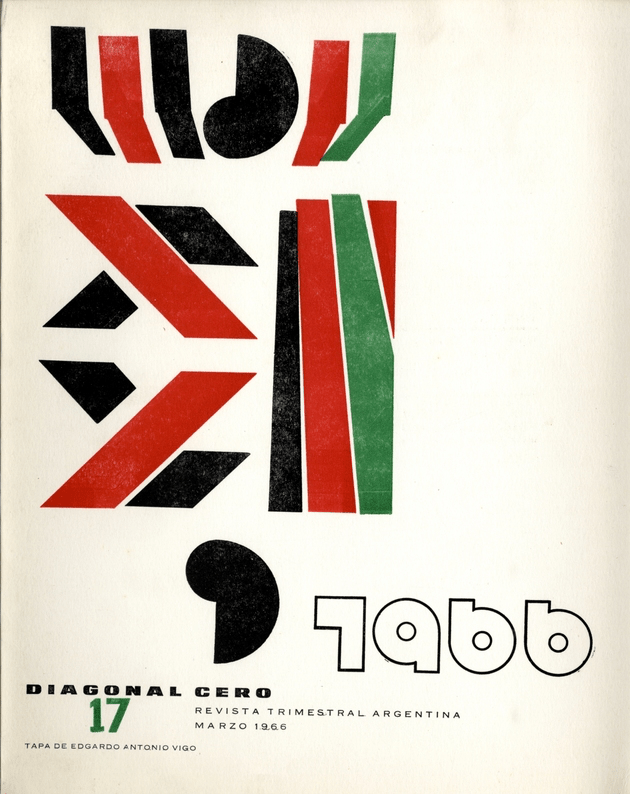

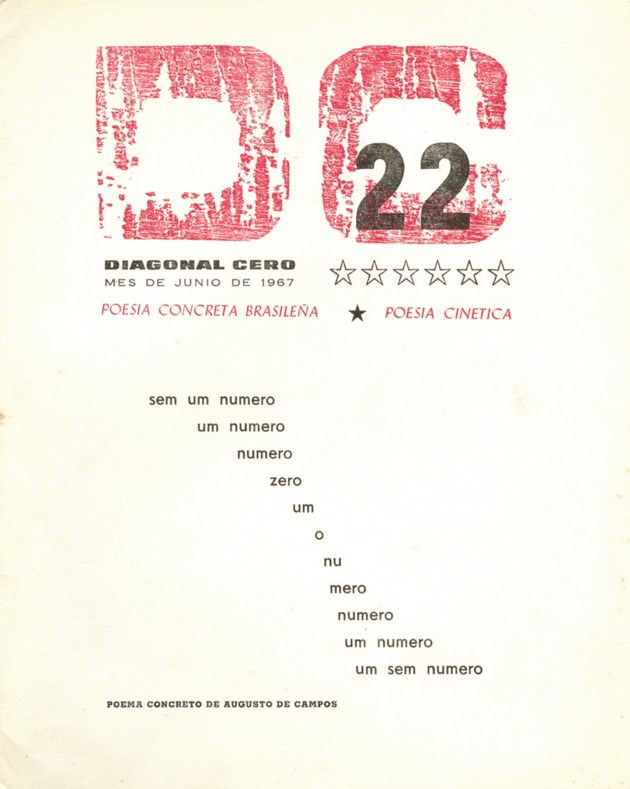

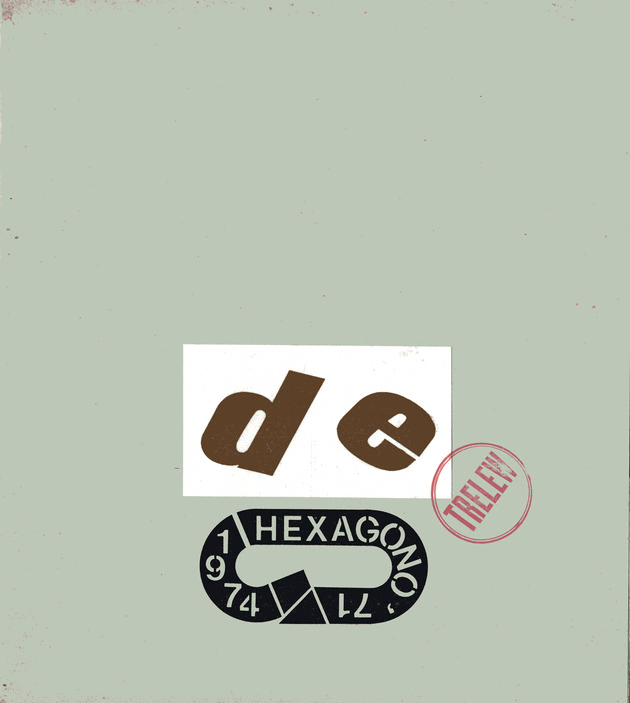

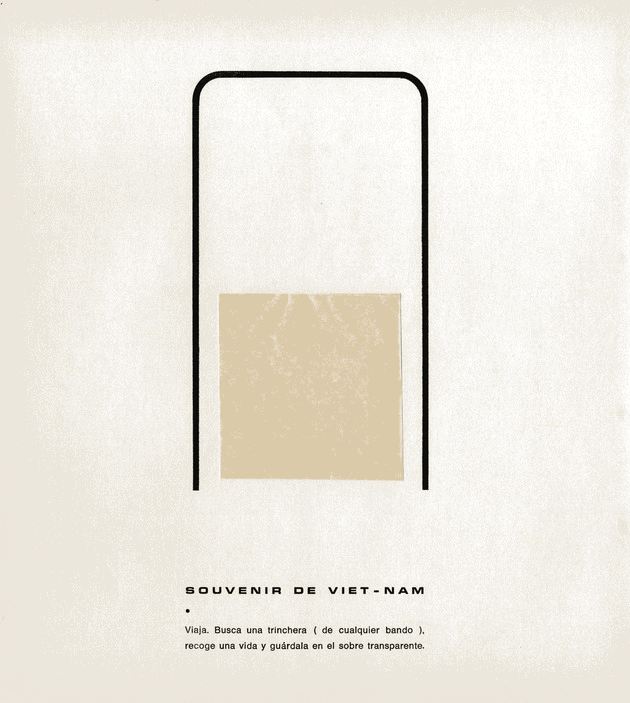

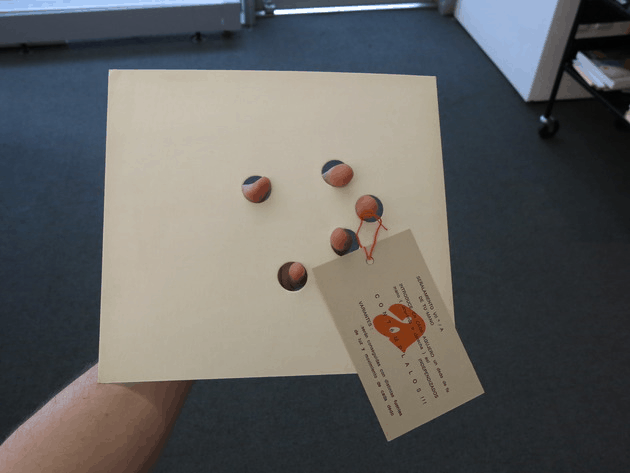

Indeed, Vigo’s works act as three-dimensional amplifications of Padín’s visual poems. The open-endedness of Vigo’s publications comes in large part from their ability to function in a spatial register that leads to a dynamic, physical relationship with the reader, as seen in the unbound publications Diagonal Cero and Hexágono ’71.25The Argentine magazine Diagonal Cero began in 1962 and ceased publication in 1969 after 28 issues (the 25th issue, dedicated to nothingness, does not actually exist, however). The magazine was named after the diagonal streets of Vigo’s hometown of La Plata and circulated internationally, cultivating Vigo’s relationships with the poets and mail artists who contributed to its pages. Even more experimental, Hexágono ’71was published between 1971 and 1975. Because their loose textual and visual components can be unfolded and juxtaposed in a variety of ways, readers can depart from the type of linear, sequential reading that fixes sense.26This nonlinearity became even more pronounced in Vigo’s subsequent publication, Hexágono ’71. Holes in some pages reframe the texts of subsequent ones, fragmenting and reconfiguring their meanings. These apertures also beg to be palpated, acting as gripping holes for fingers. Usually perceived as abstracted spaces for words, pages thus suddenly gain weight as objects to be manipulated and perceived from multiple angles. Vigo therefore deconstructs the journal as a medium, pushing meaning into an acute state of flux, even nonsense. Self-aware, Diagonal Cero announces in its first issue: “We are contradictory. Contradiction is equivalent to expressive liberty.” Once Argentina’s dictatorship garroted this freedom, Diagonal Cero ceased publication in 1969, ruing this outcome with a final statement sufficiently ambiguous to operate as both a lament about itself and a threat to the regime: “No VA MÁS” (It cannot go on).27In 1969, the ruthless dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía, who had been in power since 1966, was in its final throes. Onganía was ultimately toppled in 1970.

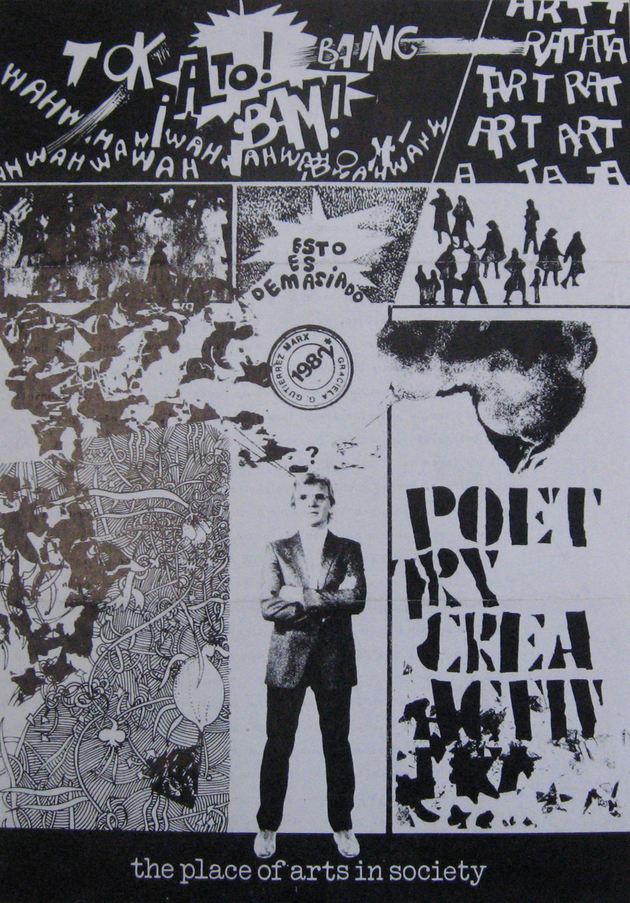

A similar cry of desperation tinged with ireful exasperation—“Esto es demasiado” (This is too much)—occupies the center of The Place of Arts in Society, a 1982 mail art piece by Argentine artist Graciela Gutiérrez Marx, a close collaborator of Vigo’s. On one level, these words can refer to the work’s dense packing of nearly undecipherable images eroded by the excess of photocopying that went into their making and dissemination. On another, the phrase denounces the ruthlessness of Argentina’s authoritarian regime, evoked by the work’s onomatopoeic transcriptions of screams and armed conflict.28In 1976, President Isabel Perón was overthrown by a right-wing military coup that placed Jorge Rafael Videla in power. His dictatorship soon launched a brutal campaign of state terrorism known as the Dirty War, which led to the disappearance of an estimated 30,000 citizens. Democracy returned to Argentina only in 1983. If, as suggested by its self-conscious title, the piece reflects on its—and, by extension, the artist’s—role within this context, Gutiérrez Marx is hard-pressed to provide any clear directives. At the epicenter of the work’s whirlwind of images and text, an immobile figure, crowned by a question mark, stands in for the nonplussed artist (or reader). To the right, letters for the words “poetry,” “create,” and “activate” deteriorate into illegible abstract signs reminiscent of Padín’s signografías (signographies), thereby conveying the increasing impotence of these concepts before intensifying state violence and acute social instability.29From 1967 to 1970, Padín created signografías—a type of visual poetry that repeats and distorts letters of the alphabet so that they become illegible and are instead appreciated as abstract forms and patterns. At the top, the “RATATATA” of firing guns gradually morphs into the word “ART.” Here, a grisly possibility emerges: that an explicitly militant mail art calling for armed resistance may have slipped into totalitarianism’s logic of violence and propaganda.30This tendency is not unique to mail art. In much Latin American art of this time, violent political action, which often put the artist’s body at risk, had become a type of “aesthetic material,” as Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman argue in Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde”: vanguardia artística y política en el ’68 argentino (Buenos Aires: El Cielo por Asalto, 2000), 255-56.

This work’s strategy of self-reflexivity as self-incrimination is also present in Happy Bicentennial. Among Latin American mail artists, the bomb was a well-established conceit for mail art.31 This metaphor conveyed the gist of “Mail Art and the Big Monster” (1977), an influential essay by Carrión, postulating: “Every invitation we receive to participate in a mail art project is part of the guerrilla war against the Big Monster. Every mail art piece is a weapon thrown against the Monster.”31Dámaso Ogaz, for example, wrote “Mail Art: A Homemade Bomb.” Paulo Bruscky and Carlos Ginzburg also used this metaphor in their writings and work. For more on the conceit of the bomb in Latin American art, see Fernanda Nogueira, “Revolution: A Collective Poem. The Poetic and Political Powers of the Mail Art Network III,” post, The Museum of Modern Art. Conjuring the image of an explosive Molotov cocktail or hand grenade, Carrión’s politically militant conceptualization of mail art as both weapon and battleground goes against North Atlantic understandings of “the eternal network.”32As argued by Colby Chamberlain, North Atlantic mail art at times sought to subvert or, at the very least, overload the mail system, as seen with the activities of George Maciunas. However, Maciunas’s campaign of “sabotage and disruption” did not have an explicitly political objective and was overwhelmingly repudiated by Fluxus artists. When figures such as Tomas Schmit, for example, suggested something as extreme as calling in bomb threats, others immediately opposed this plan, decrying it “antisocial and hurtful.” Chamberlain, “International Indeterminacy: George Maciunas and the Mail,” ARTMargins 7, no. 3 (October 2018): 73, 74. “Correspondence art can express concern with crucial issues of the day without assuming the responsibility for producing real effects or responding to challenging feedback,” writes Michael Crane33Michael Crane, “A Definition of Correspondence Art,” in Correspondence Art, 3. —an attitude that leads many in the eternal network to ask, “Is there a mail art ivory tower, or what?”34Chris Dodge and Jan DeSirey, “Mail Art, Librarians, and Social Networking,” in Eternal Network, 199. Generally, artists of the North Atlantic had a utopian view of the mail art network as an inherently democratic, gregarious, and anti-commercial “global village”35Ken Friedman, “Foreword: The Eternal Network,” in ibid., xv. ruled by a humanist “ethos” and capable of promoting freedom, dialogue, cooperation, and even spirituality.36Ken Friedman writes, “The Eternal Network placed its stress on dialogue . . . on the community of discourse.” Ibid., xv–xvii. Chuck Welsh similarly describes the eternal network as a community made up of “legions of like-minded mail artist who believe in process art aesthetics, which include inter-action, inter-connection, cooperation, and global cooperation.” Emphasizing the “mystical utopianism” of mail art, he adds: “Cooperation and participation, and the celebration of art as a birthing of life, vision, and spirit are first steps. The artists who meet each other in the Eternal Network have taken these steps.” See Welsh, “Introduction: The Ethereal Open Aesthetic,” in ibid., xviii, xx. “It has been said that mail art is easy, cheap, unpretentious and democratic. All this is rubbish,” Carrión counters.37Carrión, “Mail Art and the Big Monster,” xvii.

Carrión’s essay never defines the “Big Monster,” preferring to let it stand for all forms of oppression. Padín’s mail art, by contrast, repeatedly takes aim at the neocolonialism of foreign corporations, primarily from the United States. Yet Happy Bicentennial targets more than this Wall Street complex. Its bomb—as both an auto-referential symbol for the mail art network and a literal weapon that risks recasting this network as a terrorist web—threatens mail art in and of itself, implicating it in nefarious systems of power. Padín’s willingness to chance sabotaging the mail art network sprung, in large part, from the artist’s growing awareness of the problematic homology, even complicity, between it and the proliferating capitalist networks that he loathed. He writes: “We [mail artists] assist . . . the globalization of the culture of the First World and the greater expansion of the transnational capitalism. . . . We know that this [networking that aspires to the universality of communication] signifies the expansion of a commercial culture and not communication and understanding between peoples. How could we resolve this contradiction?”38Ruud Janssen, The Mail-Interview with Clemente Padín (Uruguay) (Tilburg, Netherlands: TAM-Publications, 1996), 12. Though cognizant of this quandary, Padín never abandoned the mail art network. Nor did it abandon him. In 1977, the Uruguayan military dictatorship imprisoned Padín for his art.39Padín went missing and was then tried before a military court, which condemned him to four years of prison. He was released on parole after serving half his sentence. For the remainder of the dictatorship, Padín could not leave Uruguay, create art, or use the postal system. Quick to mobilize and exert political pressure, mail artists from around the world secured Padín’s release within two years, demonstrating through this effort the redeeming potential of their Janus-faced network.

- 1Soon after his election, in 1972, President Juan María Bordaberry suspended the constitution and began ceding power to the armed forces. In June 1973, the military consolidated its control over the nation through a coup in which Bordaberry willfully participated, becoming a puppet of the military until he was fully ousted in 1976. The authoritarian regime would remain in power until 1985. During the tumultuous mid-1970s, Padín was receiving and sending mail only through third parties rather than through the post. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019.

- 2In the mid-1970s, Ulises Carrión began Daylight Press, an editorial name and address in Amsterdam for artists to use in the creation of their own publications. Michael Gibbs, Eduard Bal, John M. Belis, and Gerrit Jan de Rook are some of the artists who made use of this press.

- 3The work entered the Franklin Furnace Archive in 1982, but its exact whereabouts between this moment and its publication in 1976 remains unclear.

- 4Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. My translation.

- 5Padín recalls that El País, the country’s leading newspaper, published these instructions. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, April 1, 2019.

- 6Starting in 1977, President Jimmy Carter’s administration imposed diplomatic sanctions on Uruguay in condemnation of the dictatorship’s violation of human rights (by then, torture, disappearances, executions, and unjustified imprisonments were well documented by Amnesty International). However, US banks and corporations continued to do business with the dictatorship, sustaining it through the economic turmoil brought on by its pariah status on the international stage. For more on this, see Isabel Clemente Batalla, “El context político international y la política exterior uruguaya durante la dictadura (1973–1985),” in El negocio del terrorismo de estado: Los cómplices económicos de la dictadura uruguaya, ed. Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky (Montevideo: Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial, 2016).

- 7Arguing for their inefficacity, Reagan reversed the sanctions of the Carter administration. For more on this topic, see ibid., 66.

- 8Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. My translation.

- 9By removing an i, Padín creates a pun by fusing the word “exploitation” with “explosion.”

- 10From Panama and Guatemala to Cuba and Chile, the United States has a long history of interventionism in the region.

- 11Luis Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007), 58. To Camnitzer, the Tupamaros “exemplify politics coming as close as possible to the art side of the line” and are the mirror image of projects such as the exhibition Tucumán Arde and, I would argue, Happy Bicentennial, which approach this limit from the side of art. Ibid., 44. The criminal outcome envisaged by Happy Bicentennial would be hard to distinguish from the Tupamaros’s own activities and subterfuges—kidnappings, bombings, and robberies, which are viewed by Camnitzer as forms of spectacular theater or performance oriented toward the media. Ibid., 49. In fact, Camnitzer concludes his chapter on the Tupamaros by citing Padín’s own words: “In a political act we find political elements, and subsequently elements that are social, religious, aesthetic, etc. Art in the street . . . assumes the aesthetic instances of politics and tries to direct them against their creators. . . . Attacking [the apparently evident, normal and natural rules] and formulating one’s own rules means to question the legitimacy of the system.” Ibid., 59.

- 12Latin American artists working in this politicized conceptual mode include Cildo Meireles, Eugenio Dittborn, Luis Camnitzer, Graciela Gutiérrez Marx, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Jac Leirner, Victor Grippo, Gonzalo Díaz, Alfredo Jaar, and the artist collective Tucumán Arde, among others.

- 13“Translating this experience [of authoritarianism] artistically in a significant way could proceed only from giving new sense to the [Latin American] artist’s role as an active intervener in political and ideological structures,” writes Mari Carmen Ramírez with regard to Latin American conceptualism in her seminal essay “Blue Print Circuits: Conceptual Art and Politics in Latin America,” in Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century, ed. Waldo Rasmussen. exh. cat (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1993), 158.

- 14Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 31, 2019. My translation. Padín today expresses a mixture of remorse and unease regarding his creation of Happy Bicentennial, which he wishes could be “erased.” Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, April 15, 2019. My translation. His trepidation regarding this work stems from his awareness that his call to bomb New York’s financial district resonates differently in a post-9/11 world than it did in the 1970s. Additionally, during his imprisonment by the military dictatorship, Padín was tortured during interrogations specifically on Happy Bicentennial. His interrogators went so far as to threaten to bomb his home and thus kill his wife and child. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, March 29, 2019. This traumatic experience informs the artist’s current misgivings about this particular work of mail art.

- 15For more on this topic, see, for example, Miguel A. López and Josephine Watson, “How Do We Know What Latin American Conceptualism Looks Like?” Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no. 23 (Spring 2010): 5–21.

- 16”Clemente Padín, “The Options of Mail Art,” in Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, ed. Chuck Welsh (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 1995), 206. My emphasis.

- 17“Stuff the small lath with powder and put the tube,” reads the booklet.

- 18Coincidentally, the combination of flowers and bomb is reminiscent of André Breton’s famous description of Frida Kahlo’s art as a “ribbon around a bomb.” André Breton, “Frida Kahlo de Rivera (1938),” in Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2002), 144.

- 19This version of Happy Bicentennial became public much later, in 1984, when reproduced in Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet, eds., Correspondence Art: Source Book for the Network of International Postal Art Activity (San Francisco: Contemporary Arts Press, 1984).

- 20Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art, 57.

- 21Clemente Padín, “Estrictamente Autorreflexivos,” in Clemente Padín: Poesías completas, ed. Carlos Pineda (Mexico City: Ediciones del Lirio, 2013), 317. My translation.

- 22“Oxímoron,” Padín explains, “is one of the poems I love the most.” He describes it as “a thing that is and isn’t at the same time.” The poem, written toward the end of the Uruguayan dictatorship, as Padín is keen to point out, alludes to the precariousness of this sociopolitical context. Clemente Padín, email correspondence with author, June 11, 2019. The poem is also alternatively titled “Estabilidad 1 (Stability 1)” and was published multiple times, most recently, in Patricia Bentancur, ed., Clemente Padín(Montevideo: Banco Central del Uruguay, 2006), 79 and Pineda, Clemente Padín: Poesías completas, 350.

- 23Clemente Padín, “Edgardo Antonio Vigo: A Libertarian Aspiration,” in Clemente Padín, ed. Bentancur, 341. In this essay, Padín links the participatory ambiguity of Vigo’s art to the work of Joseph Kosuth and Marcel Duchamp. The latter artist represents to Padín “the most significant precedent” for mail art. See Clemente Padín, “Arte correo: 50 años desde la óptica latinoamericana,” Arte y Parte, no. 101 (2012): 17. My translation. Though Padín only cites Duchamp’s postcards as an example of mail art avant la lettre, the Uruguayan artist’s interest in Duchamp is also due to the ambiguity produced by the French artist’s myriad double entendres. Unsurprisingly, the title of Padín’s 2003 poetry book, La poesía es la poesía, employs a strategy of nominalism stretching back to Duchamp, as Martín Palacio notes. See Palacio, “La poesía es la poesía,” in Clemente Padín: Poesías completas, 307.

- 24Clemente Padín, “Estrictamente Autorreflexivos” in ibid., 317. My translation.

- 25The Argentine magazine Diagonal Cero began in 1962 and ceased publication in 1969 after 28 issues (the 25th issue, dedicated to nothingness, does not actually exist, however). The magazine was named after the diagonal streets of Vigo’s hometown of La Plata and circulated internationally, cultivating Vigo’s relationships with the poets and mail artists who contributed to its pages. Even more experimental, Hexágono ’71was published between 1971 and 1975.

- 26This nonlinearity became even more pronounced in Vigo’s subsequent publication, Hexágono ’71.

- 27In 1969, the ruthless dictatorship of General Juan Carlos Onganía, who had been in power since 1966, was in its final throes. Onganía was ultimately toppled in 1970.

- 28In 1976, President Isabel Perón was overthrown by a right-wing military coup that placed Jorge Rafael Videla in power. His dictatorship soon launched a brutal campaign of state terrorism known as the Dirty War, which led to the disappearance of an estimated 30,000 citizens. Democracy returned to Argentina only in 1983.

- 29From 1967 to 1970, Padín created signografías—a type of visual poetry that repeats and distorts letters of the alphabet so that they become illegible and are instead appreciated as abstract forms and patterns.

- 30This tendency is not unique to mail art. In much Latin American art of this time, violent political action, which often put the artist’s body at risk, had become a type of “aesthetic material,” as Ana Longoni and Mariano Mestman argue in Del Di Tella a “Tucumán Arde”: vanguardia artística y política en el ’68 argentino (Buenos Aires: El Cielo por Asalto, 2000), 255-56.

- 31Dámaso Ogaz, for example, wrote “Mail Art: A Homemade Bomb.” Paulo Bruscky and Carlos Ginzburg also used this metaphor in their writings and work. For more on the conceit of the bomb in Latin American art, see Fernanda Nogueira, “Revolution: A Collective Poem. The Poetic and Political Powers of the Mail Art Network III,” post, The Museum of Modern Art.

- 32As argued by Colby Chamberlain, North Atlantic mail art at times sought to subvert or, at the very least, overload the mail system, as seen with the activities of George Maciunas. However, Maciunas’s campaign of “sabotage and disruption” did not have an explicitly political objective and was overwhelmingly repudiated by Fluxus artists. When figures such as Tomas Schmit, for example, suggested something as extreme as calling in bomb threats, others immediately opposed this plan, decrying it “antisocial and hurtful.” Chamberlain, “International Indeterminacy: George Maciunas and the Mail,” ARTMargins 7, no. 3 (October 2018): 73, 74.

- 33Michael Crane, “A Definition of Correspondence Art,” in Correspondence Art, 3.

- 34Chris Dodge and Jan DeSirey, “Mail Art, Librarians, and Social Networking,” in Eternal Network, 199.

- 35Ken Friedman, “Foreword: The Eternal Network,” in ibid., xv.

- 36Ken Friedman writes, “The Eternal Network placed its stress on dialogue . . . on the community of discourse.” Ibid., xv–xvii. Chuck Welsh similarly describes the eternal network as a community made up of “legions of like-minded mail artist who believe in process art aesthetics, which include inter-action, inter-connection, cooperation, and global cooperation.” Emphasizing the “mystical utopianism” of mail art, he adds: “Cooperation and participation, and the celebration of art as a birthing of life, vision, and spirit are first steps. The artists who meet each other in the Eternal Network have taken these steps.” See Welsh, “Introduction: The Ethereal Open Aesthetic,” in ibid., xviii, xx.

- 37Carrión, “Mail Art and the Big Monster,” xvii.

- 38Ruud Janssen, The Mail-Interview with Clemente Padín (Uruguay) (Tilburg, Netherlands: TAM-Publications, 1996), 12.

- 39Padín went missing and was then tried before a military court, which condemned him to four years of prison. He was released on parole after serving half his sentence. For the remainder of the dictatorship, Padín could not leave Uruguay, create art, or use the postal system.