“Let’s convert all the systems into poetry and visions.” Felipe Ehrenberg, Telegraphic Work, 1970.

In this text, Zanna Gilbert explores the Work Secretly titled Upwards and Onwards…whether you like it or not by the Mexican artist Felipe Ehrenberg, considering how mail art works continue to provoke even years after their inception.

“Let’s convert all systems into poetry” was the ludic proposition stated in Felipe Ehrenberg’s 1970 Telegraphic Work.1Ehrenberg made the statement in his Telegraphic Work, a telegram which contained the statement: “CONVIRTAMOS/TODOS/LOS SISTEMAS /EN/POESIA/Y/VISIONES/Y/RECUERDAN/QUE/LA/

CREACIÓN/ES FUERZA/MIENTRAS/QUE/EL/ARTE/SIGNIFICA/EL/

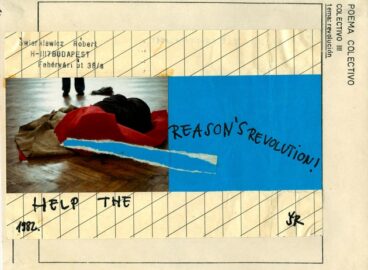

PODER/REPITO/EL PODER/FIN/DE/MENSAJE/FELIPE/.” Tate Gallery Archive: 815.2.2.4.200 At the end of that same year, this strategy of exploiting an official system for artistic purposes found expression in one of Mexico’s first major mail art works: Obra Secretamente titulada Arriba y Adelante . . . y si no pues tambien (Work Secretly titled Upwards and Onwards . . . whether you like it or not). The work signaled an appropriation of media and communication systems for artistic purposes and a commitment to collective production that would be developed in the mail art network in the next decade, reaching its zenith in the Poema Colectivo: Revolución more than a decade later. Like the Poema Colectivo, the work’s resuscitation today raises questions about the relationship between these early forms of collective networked artistic activity and our contemporary hyper-networked condition, about the reproduction and reconstruction of these works for exhibitions or for sale, about ways of resisting surveillance culture and censorship, and about how artists and thinkers might be “polled” for their ideas on societal transformations.

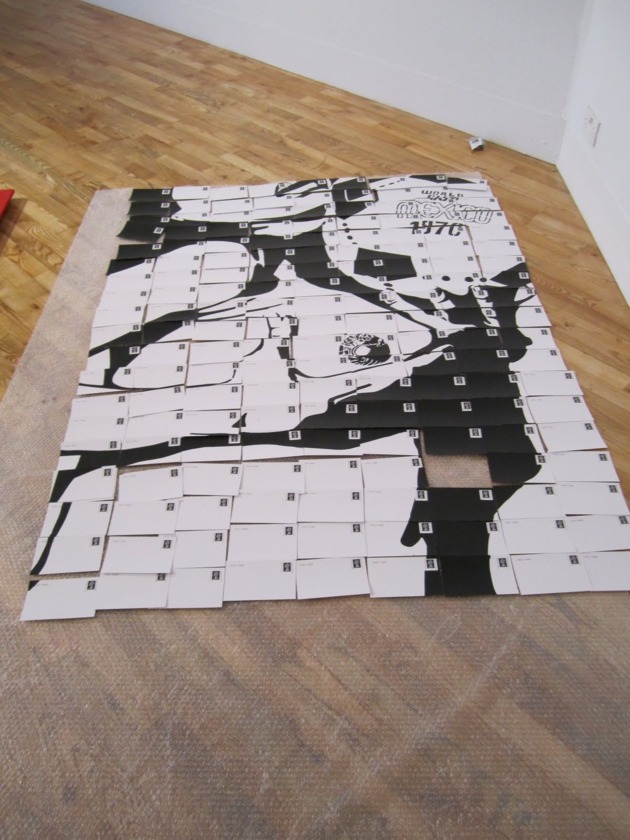

Arriba y Adelante, as it has come to be known, was an ambitious work whose chosen system for conversion into poetry was the postal service. Conceived as a conceptual puzzle, it was made up of two hundred prestamped postcards, on each of which Ehrenberg painted an unrecognizable shape. When later assembled in a given order, the postcards formed a painting depicting a larger-than-life topless woman proffering one of her breasts with one hand and holding a soccer ball branded “Mexico ’70” in the other. The image was copied from one of a collection of nude photo shots published in England on the occasion of Mexico’s hosting of the World Cup. Ehrenberg converted this celebratory soft porn photograph into a Pop-influenced, black-and-white, stylized art piece. However, unlike a Pop work, Arriba y Adelante traveled through the media and communications circuits that it commented upon: On November 15, 1970, Ehrenberg sent the two hundred postcards from three different post offices in London. Each was addressed to the Mexican Independent Salon, which was about to hold its third exhibition at Mexico City’s University Museum of Science and Art (MUCA).

1970 was also a year of presidential elections in Mexico. Ehrenberg took as the title of his work Luis Echeverría’s campaign slogan, a maxim denoting a politics of desarrolismo (“developmentalism”) closely tied to Mexico’s role as host of the 1968 Olympic Games and the 1970 World Cup, events that offered up a commodified image of a country ripe for international investment. Interior Minister since 1964, Echeverria was widely considered responsible for the Tlatelolco massacre of October 2, 1968, in which government forces opened fire on a peaceful student protest just days before the opening of the Olympics. Hundreds are thought to have been killed.2The number of dead is still unknown, the official figure being around forty, but groups such as Comité 68 who continue to campaign for transparency estimate the death toll to be more than three hundred. In 2006 Mexico’s ex-president Luis Escheverría, interior minister at the time of the massacre, was arrested on charges of genocide, but the charges were eventually dismissed. Ehrenberg and his family decided to leave Mexico for England in the wake of that state-perpetrated violence.

Why did Ehrenberg choose to construct his entry to the Independent Salon in such a way? On one level, his strategy solved the practical problem of his dislocation: he was far from Mexico, and his participation in the exhibition necessarily required a journey of some sort. The disembodied journey he devised was part and parcel of the work’s meaning. Moreover, the Mexican postal system refused to carry pornographic material of any sort, and, as Ehrenberg pointed out, criticism of the government was a risky business.3Instructions for a work secretly entitled Arriba y Adelante . . . y si no, pues tambien, November 1970, Tate Gallery Archive: 815.2.2.4.201. Not only could the multipartite piece, illegible in its fragmented state, evade moral and political censorship, but also the critique of government systems was redoubled by the postcards’ passage through the mail service, a branch of the very thing the work criticized.

Ehrenberg’s written instructions for installing Arriba y Adelante were as follows: “During the opening night of the Third Annual Exhibition of the Independent Salon, and after a respectable amount of citizens are gathered, my duly appointed representative shall begin by tacking up each card in order. . . . Members of the public are happily invited to help.”4Ibid.

Just as Echeverria’s sloganeering concealed a pernicious, violent approach to politics, Ehrenberg’s lighthearted directions for assembling the work overlay a deadly serious point. Arriba y Adelante was to be mounted on a red backing, so that any failure of the postal system to deliver a postcard would be represented by a crimson gap, effecting a visual correlation between the inefficiency of the postal bureaucracy, specifically identified by Ehrenberg as “a government institution,”5Ibid.and the violent means pursued by the government to control the student movement. At the same time, the work playfully mocks the British postal system’s reputation for impersonal efficiency as well as its figurehead, Queen Elizabeth.6The United Kingdom’s Royal Mail is the only postal service in the world that does not print the name of the country on its stamps, but instead the figurehead of the monarch. The monarch’s profile on each of the stamps is overwhelmed and rendered ridiculous by Ehrenberg’s outsized, overtly sexualized figure.

More than forty years later, in 2011, Arriba y Adelante was included in the exhibition Intimate Bureaucracies: Art and the Mail, at the University of Essex (U.K.). Since the whereabouts of the original work is unknown (the piece was presumably destroyed after being exhibited at the Independent Salon), it was decided that the work would be re-created for the show with Ehrenberg’s help. Some twenty-first-century issues were provoked by the work’s ephemerality. The Royal Mail no longer produced prestamped postcards, and so a facsimile produced by Mauricio Marcin for his 2010 exhibition Arte Correo en Mexico (Mail Art in Mexico) at the Museo de la Ciudad in Mexico City would be used. The file was sent by email and printed by the university’s printer. When we came to assemble the work, the logic of its reconstitution was unclear; somehow the order of the postcards had been lost in the translation from digital file to printer. A long afternoon was spent puzzling out how to assemble the pieces, showing just how effectively the work must have concealed its meaning in its original transit. We constructed the copy with the original work’s ephemerality in mind, paying attention only to the immediate challenge of mounting the exhibition.

After many mail-related adventures, the exhibition closed, and we had to decide what to do with this version of Arriba y Adelante. Doubts over the status and value of the work began to emerge: Was it a facsimile, an exhibition copy, or a replica? Should it enter the Essex Collection of Latin American Art (ESCALA), or be stored in the archive? Should it be destroyed in order to assure the integrity of the edition then being produced by Ehrenberg’s gallery in São Paulo?

I had a fascinating exchange with Ehrenberg over these matters, and he kindly offered to produce a new iteration of the work as a gift to ESCALA. We decided to destroy the version that had been made for the exhibition and to accept Ehrenberg’s offer of a new one, which would be sent by post from São Paulo. While all of these questions were being considered, and long after the other works in the show had been safely shipped back to their owners, Arriba y Adelante languished in the gallery.

The following week, the porters charged with clearing out the gallery space removed the work and disposed of it in the bowels of the university. A few days later, one of the gallery staff members came across it, weather-beaten and vandalized, resting unobtrusively against a skip. There, the logic of its insistent ephemerality, of its belonging to a space other than the gallery, was more apparent than ever, even so many years after its original inception. Just as the Poema Colectivo is redeployed here on post with a renewed significance, Ehrenberg’s work also spoke once again to a new moment. Mail art and its archives continue to provoke, to make us consider and reconsider the politics of art and the potential for collective action. This performative aspect of mail art confers a continually evolving meaning, hinting at a journey that is as much temporal as it is geographic.

This is a revised version of a text published in Spanish in the magazine Blanco sobre Blanco.7See Zanna Gilbert, “La lógica de los fragmentos: Obra secretamente titulada Arriba y Adelante… y si no, pos también”, in Blanco sobre Blanco. Miradas y lecturas sobre artes visuales, n. 2, Buenos Aires, March 2012, pp. 55-58.

- 1Ehrenberg made the statement in his Telegraphic Work, a telegram which contained the statement: “CONVIRTAMOS/TODOS/LOS SISTEMAS /EN/POESIA/Y/VISIONES/Y/RECUERDAN/QUE/LA/

CREACIÓN/ES FUERZA/MIENTRAS/QUE/EL/ARTE/SIGNIFICA/EL/

PODER/REPITO/EL PODER/FIN/DE/MENSAJE/FELIPE/.” Tate Gallery Archive: 815.2.2.4.200 - 2The number of dead is still unknown, the official figure being around forty, but groups such as Comité 68 who continue to campaign for transparency estimate the death toll to be more than three hundred. In 2006 Mexico’s ex-president Luis Escheverría, interior minister at the time of the massacre, was arrested on charges of genocide, but the charges were eventually dismissed.

- 3Instructions for a work secretly entitled Arriba y Adelante . . . y si no, pues tambien, November 1970, Tate Gallery Archive: 815.2.2.4.201.

- 4Ibid.

- 5Ibid.

- 6The United Kingdom’s Royal Mail is the only postal service in the world that does not print the name of the country on its stamps, but instead the figurehead of the monarch.

- 7See Zanna Gilbert, “La lógica de los fragmentos: Obra secretamente titulada Arriba y Adelante… y si no, pos también”, in Blanco sobre Blanco. Miradas y lecturas sobre artes visuales, n. 2, Buenos Aires, March 2012, pp. 55-58.