“American art that lost its glory” was the way Shinohara Ushio summed up Twenty Years of American Painting, an exhibition sent to Tokyo by New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1966. Just two years earlier, Shinohara had been an enthusiastic “imitator” of American artists, copying works by the likes of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and George Segal. If Shinohara’s copies of the works of American modern masters are not naïve imitations but rather critiques of the concept of originality itself, what messages do they convey? Hiroko Ikegami reveals how Tokyoite/New Yorker Shinohara started to “pop” in his own style after he stopped producing Imitation Art.

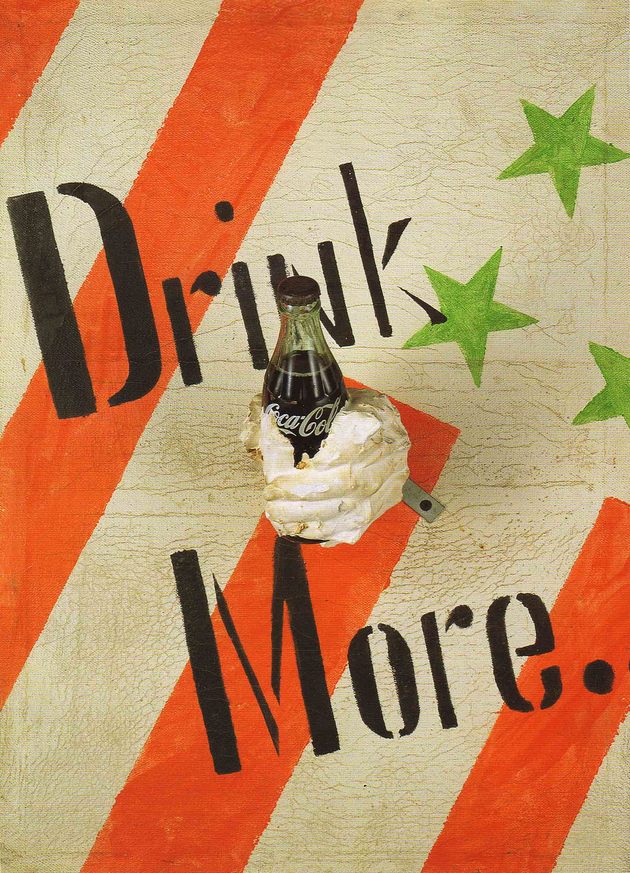

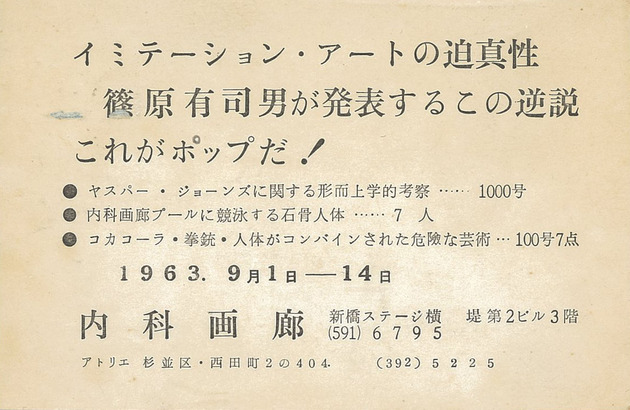

When it comes to the topic of New Yorkers in Tokyo in the 1960s, Shinohara Ushio was the single most important artist among those who interacted with them in the city (fig. 1). With his sensational Mohawk hairdo, he had made his name as a regular of the legendary Yomiuri Independent Exhibition,1With its no-jury, no-prize policy, Yomiuri Independent Exhibition, held by the Yomiuri Newspaper company from 1949 to 1963, presented an annual occasion for young artists to exhibit anything they created. a founding member of the short-lived Neo Dada group,2The Neo Dada group in Japan was founded in Tokyo in 1960 and was active for about six months. Its representative members included Yoshimura Masanobu, Shinohara Ushio, Akasegawa Genpei, and Arakawa Shūsaku. and the “action” artist of the series of Boxing Paintings made in the early part of the decade. His work took a sharp “American” turn in 1963, when he started making Imitation Art based on reproductions of works by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. When these American artists visited Japan in 1964, Shinohara showed them his imitations of their work, including Three Flags and Coca-Cola Plan. Inspired by Pop art, he began the Oiran (high-class courtesans) series the following year and wrote about his encounter with American art in his autobiography Avant-Garde Road, published in 1968.3Shinohara Ushio, Zen’ei no michi (Avant-garde road), (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 1968). This essay examines how Shinohara’s dialogue with American art developed from Imitation Art—arguably a precursor of the postmodernist critique of originality—to the Oiran series, a kind of Pop ukiyo-e, with which he achieved his own style of Pop art by combining mechanical modes of production with motifs from the popular culture of premodern Japan.

Encounter with American Neo-Dada and Pop

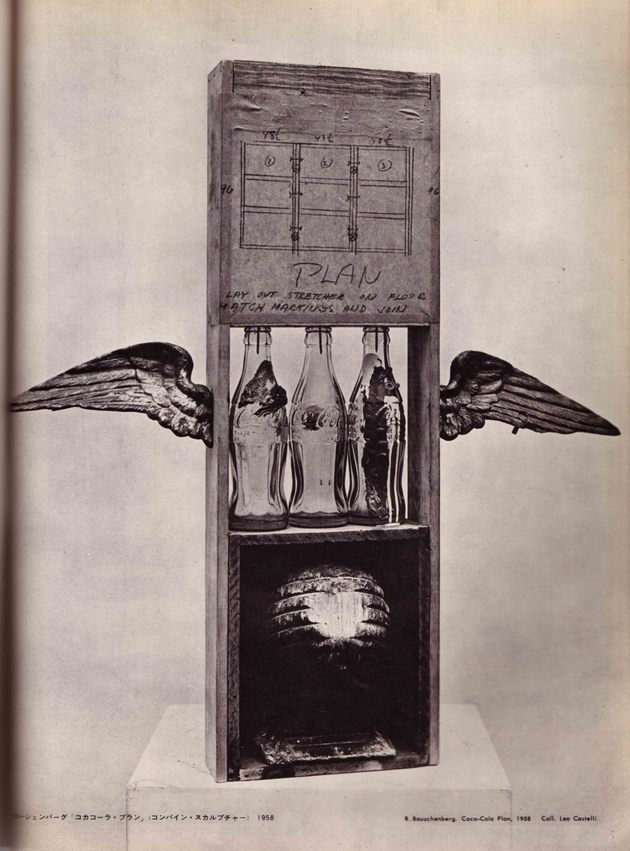

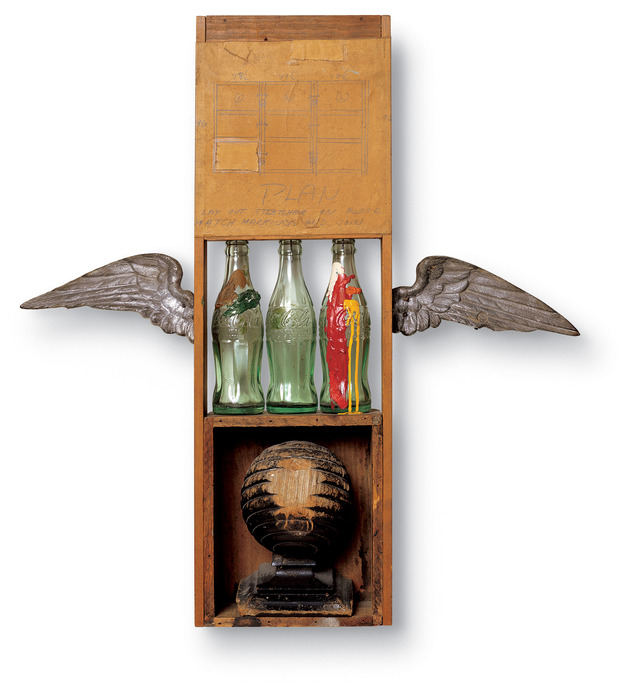

Before everything, how did Shinohara encounter postwar American art? A key figure here is the critic Tōno Yoshiaki, who promoted post–Abstract Expressionist art in Japan. He introduced works by Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg for the first time to the Japanese audience in the art journal Geijutsu shinchō (New trends in art) in 1959.4Tōno Yoshiaki, “Kyōki to sukyandaru: Katayaburi no sekai no shinjin tachi” (Madness and scandal: Fanastic new faces of the world), Geijutsu shinchō 10, no. 11 (November 1959), pp. 104–112. In 1962, in another art journal Mizue (Watercolor), he published a long essay on Rauschenberg with a number of illustrations.5Tōno Yoshiaki, “Robāto Raushenbāgu arui wa Nyū yōku no ‘Jigoku hen’” (Robert Rauschenberg, or the New York inferno), Mizue, no. 683 (February 1962), pp. 42–56. Among these was the photographic reproduction of Coca-Cola Plan (1958) that Shinohara would use as the model for his imitation of the work. Given the scarcity of information on overseas art movements at the time, the importance of art magazines as a source of inspiration for Japanese artists cannot be overestimated. In fact, some avant-garde artists in Tokyo were so eager to learn about and absorb the new art movements that were emerging one after another in New York that they felt they barely had enough time to develop their own style.

Shinohara discusses this impatience to keep up with the latest New York art movements in his autobiography Avant-Garde Road, which he serialized in Bijutsu techō (Art notebook) from 1966 to 1967.6Shinohara’s autobiography was originally titled The Road to the Avant-Garde. The name was changed to Avant-Garde Road when it was published as a book in 1968. In this memoir, he candidly relates his amazement at the quick pace of shifting styles in New York when he and his friends saw the January 1963 issue of Art International. Declaring the arrival of Pop art, this issue features two articles related to the New Realists show at Sidney Janis Gallery. The impact of American Pop art was so enormous that he responded excitedly, “The first one to imitate will win.”7Shinohara, Avant-Garde Road, p. 118. Turning away from his performance-based Boxing Painting series, he decided to create a work of Pop art to submit to the Shell Art Award Exhibition in July 1963.

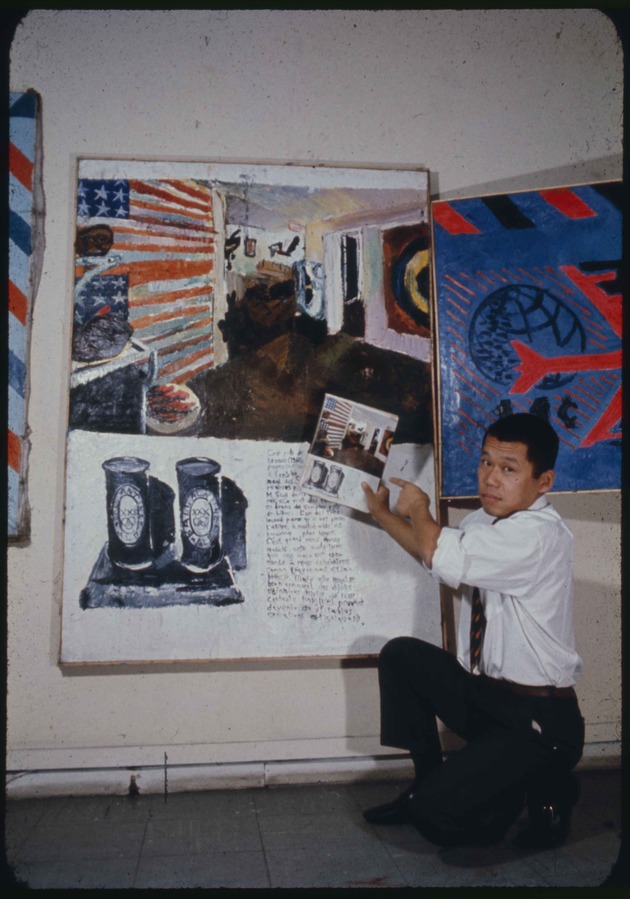

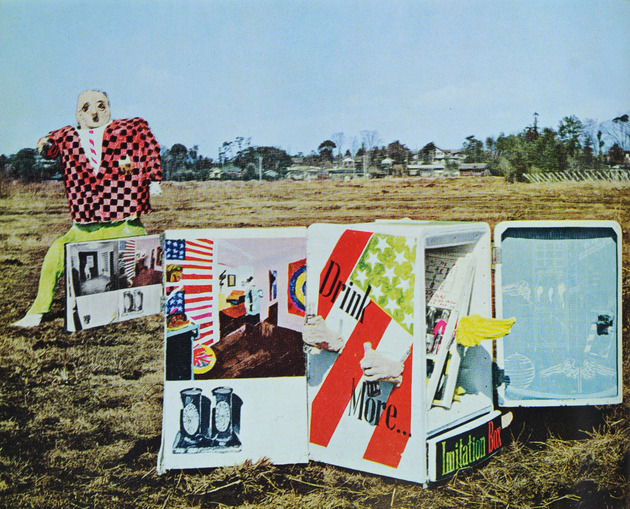

He then faced a dilemma: although Pop art was certainly a new style, its imitation by a Japanese artist wouldn’t qualify as new anymore. As he explains in his biography, “If you used food, that would be an Oldenburg, while human figures are taken by Segal, comics by Lichtenstein, flags by Johns, paint-pouring by Rauschenberg. There is no new style anywhere anymore. Shit! Why don’t I do all of them at once then!”8Ibid., p. 131. He thus made his first imitation work, Drink More (fig. 2)—originally titled Lovely Lovely America, itself a significant title—an assemblage work with the Stars and Stripes painted in the background, from which protruded a plaster hand holding a Coca-Cola bottle. The work was a desperate attempt to emulate Johns, Rauschenberg, and Segal all at the same time in a single work. Shinohara exhibited the piece along with other works in a similar vein at Naiqua Gallery in September 1963, proclaiming, “This is Pop!” (fig. 3).

Imitation Art as Originality Critique

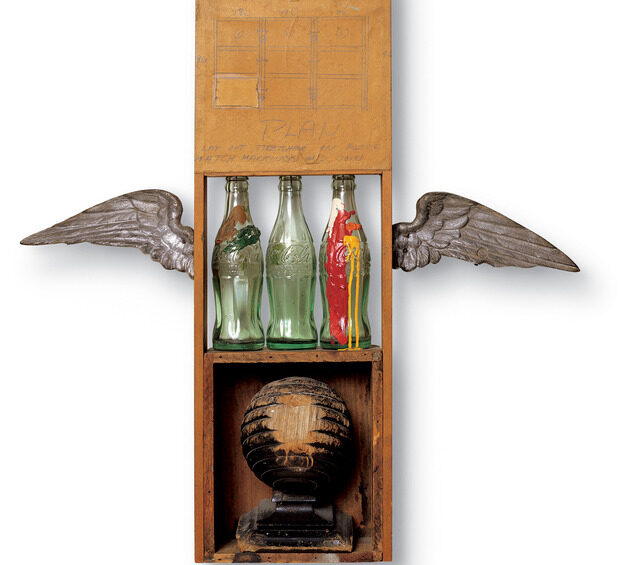

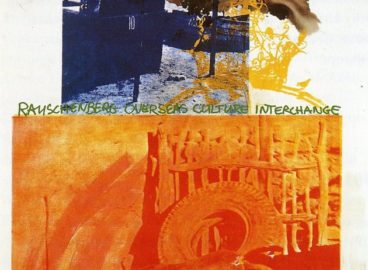

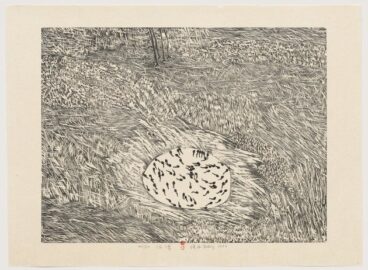

In 1964, Shinohara went on to produce a more or less exact copy of an original, based on the full-page reproduction of Rauschenberg’s Coca-Cola Plan in Tōno’s essay (figs. 4, 5, 6). However, Shinohara was not mindlessly imitating Rauschenberg as his cultural superior. Seen side by side, the difference between the original and the imitation is clear. For instance, because he could find them easily, Shinohara used Coca-Cola bottles made in Japan with logos in Japanese katakana (the syllabary used to represent foreign words phonetically). Likewise, he hand-made a mold from clay to cast the wings in plaster, as prefabricated cast-metal wings were not available in Japan. Finally, he painted the work with Day-Glo paint, because he was working with a black-and-white reproduction and didn’t know what colors had been used in the original. The resulting work indicates that Shinohara was likely playing with these altered details. This playful quality makes his work not so much a copy as a parody of the original.

Yet, calling an imitation one’s own work of art required considerable courage in the mid-1960s, when the concept of originality was generally still an incontestable credo of modern art. Shinohara recalls the embarrassment and exaltation that he simultaneously felt at the completion of the imitation: “My mother yelled at me, ‘What a shame to copy someone’s work!’ but I was filled with excitement to complete the work while feeling guilty.”9Shinohara Ushio, “Coca-Cola Plan Episode,” an unpublished statement prepared for the exhibition Shūzo Takiguchi: Drifting Objects on Dream, held at Toyama Prefectural Hall Museum, 2001. The reaction of Shinohara’s mother, a painter herself, shows her belief in the concept of originality, which is precisely what her son was questioning. In those days, Shinohara was discontent with Japanese academic art education, which called for students to develop their own original styles yet had not changed its traditional teaching method of requiring them to copy old masters and plaster models. Enclosed within the tradition of yōga—Western-style oil painting—the model of originality in Japanese art schools was still that of French modernism, exemplified by such painters as Cézanne, van Gogh, and Gauguin, or Picasso and Matisse for a more contemporary version.10Shinohara Ushio, interview with the author, July 3, 2003, Brooklyn.

Shinohara called that situation “cultural seclusion,” which he ironically associated with Japan’s “island-nation” attitude toward foreign cultures during its period of national seclusion from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Against this background, Shinohara’s imitation of Rauschenberg can be seen as an ironic three-dimensional copy of a modern master, as opposed to the reverent two-dimensional copying of old masters required by art schools. Theorizing on his Imitation Art series after the fact, Shinohara declared: “After all, Imitation Art denies originality. In other words, there is no more time to pursue form or self in modern times. It’s more interesting to copy someone else’s work in this situation.”11Quoted in Miyakawa Atsushi, “Anti-Art: Its Descent to the Everyday,” Bijutshu techō, no. 234 (April 1964), p. 49.

What Shinohara describes as a phenomenon unique to his own time had been in fact an ongoing problem in Japanese art for centuries. The question of originality has always been an issue in the discourse of Japanese art history, for Japanese art developed by responding to information and techniques brought from abroad: Chinese influence (often via the Korean Peninsula) in its premodern era, European influence in its post-seclusion period, and then American influence after World War II. This history resulted in a perpetual identity crisis in Japanese art—especially in the modern era, when the system of “art” and the concept of “originality” imported from the West required Japan to create both its own unique art and its own art history. Since the Meiji era (1868–1912), many Japanese artists had gone to Europe to learn oil painting techniques and the latest currents of modern art, passing on the information to the Japanese art community upon their return home. Much Japanese modern art thus developed through responding to Western modern art, the perceived cultural superior.

This dynamic of response to a foreign source posed a serious dilemma for many Japanese artists, as it made it next to impossible for them to achieve “originality,” a prerequisite of modern art. In order to become practitioners of modern art, they first needed to acquire its basic vocabularies and then to keep up with its development, but doing so made them perpetual followers of Western art, which kept them from becoming equal and original players in the world art scene. As we have seen earlier, this dynamic remained unchanged after the end of World War II. Shinohara’s version of Coca-Cola Plan is thus a visual embodiment of this most fundamental issue in Japanese art, while simultaneously serving as a critique of the myth of originality that haunted its discourse. Ironically, Imitation Art proved that the “avant-garde road” in Japan might actually lie in imitation rather than originality, and thereby radically debunked the concept of originality as a sustaining myth for the avant-garde.

Meeting with Bob Rauschenberg

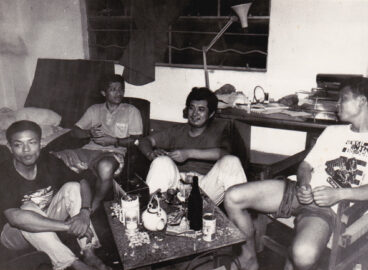

If this was the significance of Imitation Art in the context of Japanese art history, how would it appear to Rauschenberg? Although Shinohara never imagined that Rauschenberg would come to Tokyo, the American artist was already aware of Japanese Pop, most likely via his friend Tōno. In 1963, he told a Japanese journalist in New York that he wanted to go to Japan to see the imitations of Pop art that he heard were increasingly being made there.12Kuwabara [Sumio], “American Artists, No. 4: Rauschenberg—Elegant Culprit of Pop Art,” Tokyo shinbun, July 29, 1963. About a year later, the day before his scheduled interview program “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg” at the Sogetsu Art Center, Tōno granted his wish by taking him to Shinohara’s home. Shinohara recollects their encounter as follows:

“I showed one work after another to Bob, who remained silent. The Beatles, Lovely Lovely America, Don Shorander with Four Gold Medals, Air Mail—it was as if I were reproducing American Pop. But Rauschenberg impressed me as expected. He never said anything cowardly, like he wanted to see something more unique to Japan. To him, the Zen country of Japan did not matter. The only thing that mattered was the confrontation between works of art.”

Shinohara then asked Rauschenberg a “special question” about Imitation Art:

“May I imitate your works?”

There it was. My special question. I thought about showing him my Coca-Cola Plan as well, but didn’t have the courage to do so. I’d bring it out during tomorrow’s public interview anyway.

“Sure.”

I was disappointed by his immediate OK. I was expecting him to hit me, or at least pause for a little bit. Well, since I got the OK in person, I will imitate his works more and more. But the outcome was the opposite, for after meeting with Bob, I lost interest in Imitation Art.13Shinohara, Avant-Garde Road, pp. 142–43.

Shinohara gave a different version of the story in an interview with the present author, claiming that he did show Rauschenberg the imitation of Coca-Cola Plan during his visit. Shinohara said the American artist was overjoyed and held the work adoringly in his arms, calling it “my son.”14Shinohara Ushio, interview with the author, July 3, 2003, Brooklyn. Whatever the case may have been, Rauschenberg was happy with the imitation as long as there was only one. Shinohara recalls that when Rauschenberg found out that the Japanese artist had actually made ten copies of the work, he seemed disturbed. As Shinohara himself would later say, “One imitation is philosophy, but ten of them makes it production!”15Ibid.Perhaps Rauschenberg acutely sensed that multiple copies could turn the original—his work, that is—into a mere commodity.

One must remember, however, that the “original” from which Shinohara modeled his imitation of Coca-Cola Plan was already a reproduction, as Shinohara created his work based on a photograph in an art journal. Moreover, the serial logic of mass production is already plainly evident in Rauschenberg’s own Coca-Cola Plan, because he incorporated not just one or two but three Coke bottles in the work. By emphasizing the underlying logic of the original, Shinohara somehow unsettled Rauschenberg, which speaks for and demonstrates the critical power of imitation. In this sense, Imitation Art was a precedent of postmodernist appropriation, in that the imitator destabilized the authority of the original. The irony is that, in this particular instance, Rauschenberg, who since the late 1950s had countered the myth of originality with works such as Factum I and Factum II (both 1957), was cast in the role of the “original.” In another essay on post, the present author shows that this irony loomed even larger during “Twenty Questions to Bob Rauschenberg,” an event in which Shinohara participated with his multiple imitations of Coca-Cola Plan.

Imitation Box: Coda to “American” Imitation

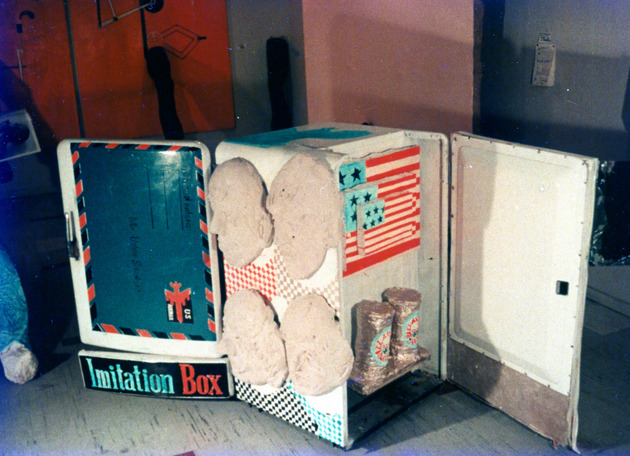

Despite receiving Rauschenberg’s permission to imitate his work, Shinohara gradually lost interest in Imitation Art and concluded the series with Imitation Box after the American artist went back to New York. In December 1964, Shinohara and his fellow artists organized a group exhibition titled Left Hook at Tsubaki Kindai Gallery, in which Shinohara exhibited Imitation Box and Marcel Duchamp in Thought (fig. 7).

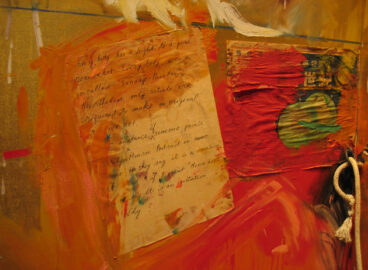

Imitation Box, which has since been destroyed, was a self-contained mini-retrospective of the Imitation Art series, featuring Shinohara’s own works, such as Drink More and Coca-Cola Plan, along with many others (figs. 8 and 9). Shinohara placed two of his Coca-Cola Plans within a discarded mini-bar-size refrigerator—itself a container of consumable products—and he used all of the flat planes to display other works. For instance, the back space of the refrigerator, which originally housed a radiator, was used to present an imitation of Johns’s Three Flags and Painted Bronze, while the side panels functioned as supports for Drink More and The Beatles. The front of the door displayed Air Mail, an imaginary letter from Rauschenberg, with the work’s title, “Imitation Box,” below it, and a study of Coca-Cola Plan was mounted on the back of the door. Furthermore, the back panel of the refrigerator bore images of Johns’s Painted Bronze and other works displayed in what appears to be a collector’s room, which was painted by hand. Upon closer inspection of a photograph of the work, we notice that the panel bears another smaller panel that holds a magazine in which the original page for Shinohara’s inspiration can be found.16The journal has not been identified. Shinohara recalls that it was a home décor magazine, not an art journal.

This sight of endless regression of American artworks seems to demonstrate the work’s logic of self-proliferation. The refrigerator is in fact a perfect “box” for carrying Shinohara’s portable works, as it is a sign of modern efficiency and consumer convenience. The refrigerator was one of the three electric appliances, or “three regalia,” that Japanese people dreamed of owning in the 1950s, along with a black-and-white television and a washing machine. In the 1960s, the three regalia were replaced by the “3 Cs”: a color television, a cooler (air conditioner), and a car. The model of this ideal domestic life was, of course, American. Japanese consumers followed trends of American life just as avidly as Shinohara followed the latest currents in the New York art scene.

Seen in this way, Shinohara’s Imitation Box aptly embodies what Homi K. Bhabha calls the “ambivalence of mimicry,” an effect created by imitating the original and multiplying it in a way that is “almost the same, but not quite.”17Homi K. Bhaba, Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 86. Containing a number of imperfect copies of American artworks, Imitation Box demonstrates the difference between “being American” and “being Americanized.” The work is reminiscent of the ways in which Japanese consumers willingly hybridized their domestic life by incorporating the American way of life haphazardly, just as Shinohara played with differences from the original art in Imitation Art. Thus, Imitation Box effects its own lighthearted and yet unsettling critique of the hegemony of American art and culture, which had had a drastic, bulldozing impact on Japan throughout the post–World War II years.

Indeed, meeting American artists in person had a demystifying effect on Shinohara. When the “cool Yankee” presented himself as a real human being to Shinohara, the Japanese artist started looking at American art differently. As a consequence, by 1966, when Twenty Years of American Painting—the first large-scale postwar American art exhibition in Japan, organized by The Museum of Modern Art in New York—opened at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, Shinohara was no longer as enthusiastic about American art. He described his disappointment in the show in his autobiography, under the subtitle “American art that lost its glory”:

“American art—this vivid monster appeared before our eyes only through journals until a couple of years ago. It seemed as if American art had been marching toward the glorious prairie of the rainbow and oasis of the future, carrying all the world’s expectations of modern painting. However, what an old sight this digest of twenty years offers us! . . . Jasper Johns’s Target or Flag was not our glorious saviour. The closer I got to Americans who came to Japan (Jasper, Jim [Rosenquist], and George [Montgomery]), the further their glory receded into the distance.”18Shinohara, Avant-Garde Road, p. 185.

Rauschenberg, who had come to Japan two years earlier, was not an exception; Shinohara no longer idolized the American artist as his hero. Therefore, Imitation Box should be understood as marking the end of Shinohara’s “imitation era,” a declaration that American art no longer represented such an immediate, irresistible appeal for him. He was ready for a new stage in his career.

How to Make Pop Ukiyo-e

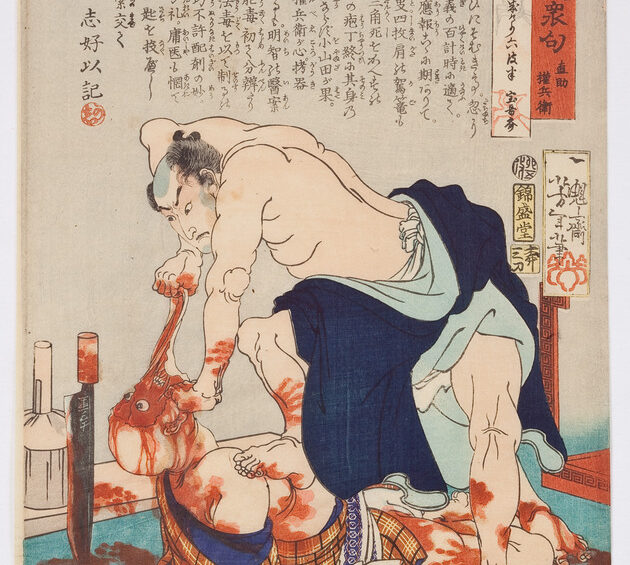

Shinohara had an epiphany in the fall of 1965, when he discovered a set of ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock prints), Twenty-Eight Famous Murders with Verse (Eimei nijūhasshū ku, 1866–67), by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi—aka Bloody Yoshitoshi. The prints depicted scenes of bloodshed based on true stories that had been adapted to Kabuki plays.19Yoshitoshi’s series was created in collaboration with Ochiai Yoshiiku. They created fourteen prints each, and Yoshitoshi selected especially bloody scenes. Shinohara saw the series in the collection of Takashi Yamamoto, the owner of Tokyo Gallery, along with works by other late-Edo masters, including Kunisada, Kuniyoshi, and Eisen.20Shinohara, in Dōru fesutibaru/Doll Festival: Onna no matsuri (Women’s festival), exh. cat. (Tokyo: Tokyo Gallery, 1966), unpaginated. Associating the gruesome subjects of these prints with ravaging images of the Vietnam War that he had seen in a TV documentary,21Ibid. he started making paintings based on these muzan-e (atrocity pictures), which developed into the Oiran series.

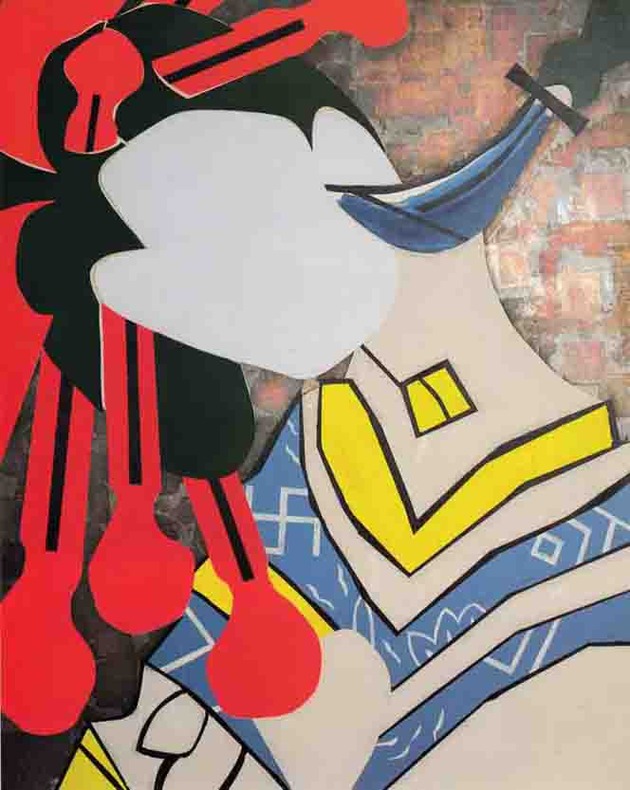

The shift from Imitation Art of American Pop to the Oiran series, inspired by gory ukiyo-e, might seem like an abrupt jump, but the mechanical processes used in making the former provided a useful technical basis for the latter. It was also a necessary step for Shinohara to further develop his image-making method. In Imitation Art, there was little room for new design, for the iconicity of the original Pop works had to be preserved for his imitations to be successful, as exemplified by the straight appropriation of Coca-Cola Plan. By contrast, for the Oiran series, Shinohara drew inspiration from ukiyo-e while reinterpreting the genre and creating his own stories or subjects by freely combining characters. His encounter with late-Edo ukiyo-e provided such impetus that he held three exhibitions on the theme within six months at Tsubaki Kindai Gallery, Naiqua Gallery, and Tokyo Gallery in 1965–66.

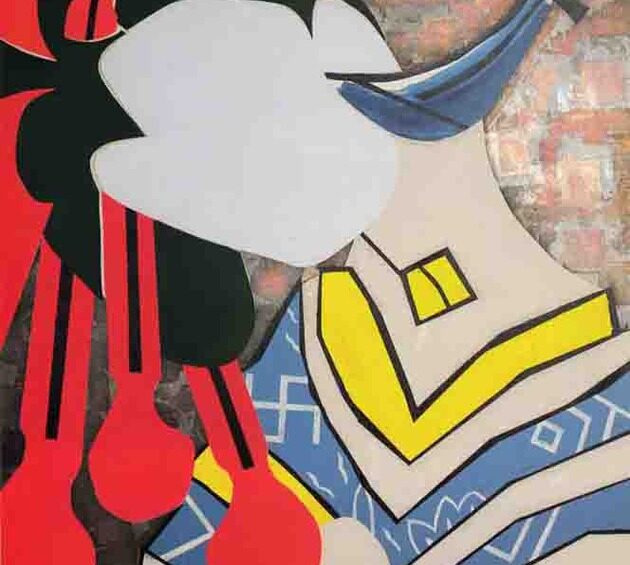

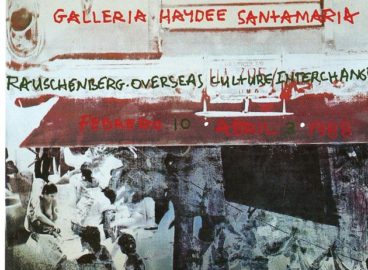

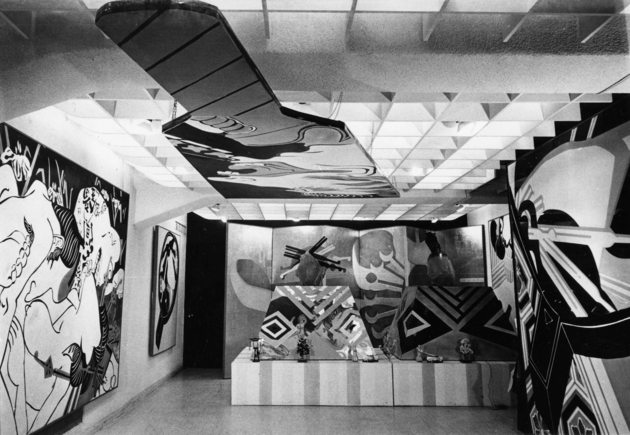

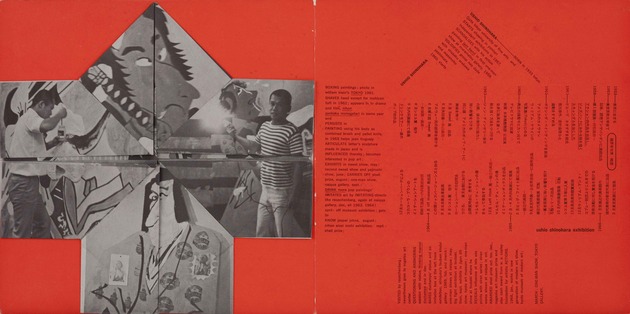

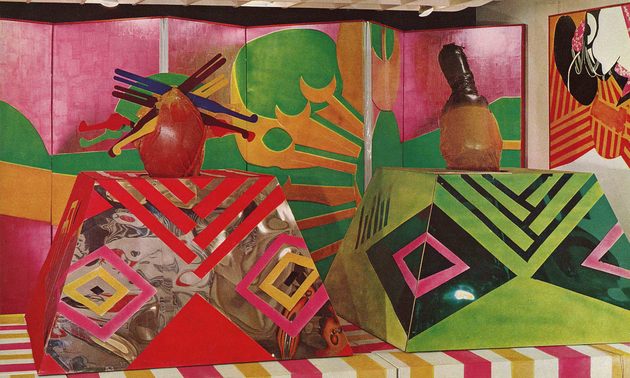

Among them, the exhibition at Tokyo Gallery in February 1966 was a tour de force, constituting Shinohara’s real debut exhibition, as it was sited at one of the few commercial galleries in Tokyo specializing in contemporary art at the time (fig. 10).22Oral History Interview with Ushio Shinohara, conducted by Hiroko Ikegami and Reiko Tomii, February 13, 2009, Oral History Archives of Japanese Art. http://www.oralarthistory.org/archives/shinohara_ushio/interview_02.php Entitled Doll Festival, the whole exhibition was carefully planned around the traditional holiday in March to celebrate girl children and was accompanied by the publication of an origami-folded catalogue (fig. 11). As gleaned from a documentary photograph of the installation, at the one end of the gallery was a pair of hina dolls, representing an imperial couple, seated on a traditionally patterned platform. Behind them was a folding screen that depicted a gaudy oiran-style kanzashi (hair ornament). Two walls were covered by large canvases that depicted various types of women, including oiran in diverse settings, with even the ceiling adorned with a gigantic hagoita (battledore) bearing the image of a monster. Three works not visible in this photograph include Doll Festival (fig. 12), a large, three-panel painting that shared the exhibition’s title.

The most noteworthy aspect of this show was its technical sophistication. While the paintings in the first two exhibitions were hand-painted in a rough and crude manner, the works in Doll Festival, prepared over a month with grant money from the Copley Foundation, demonstrated the artist’s mechanical mode of production, in which he entirely did away with brushwork. To make them, Shinohara not only employed such tools as stencils, masking tape, and an airbrush, as he had done with Drink More, but also exploited new industrial materials including fluorescent paint, aluminum sheets, metal foil, and acrylic sheets. In order to ensure a professional finish, he even had the plastic sheets cut with a power saw at a sign maker’s shop in the shapes of motifs such as kanzashi and a woman’s face, which he attached to the canvas.23Shinohara, telephone conversation with the author, June 29, 2012.

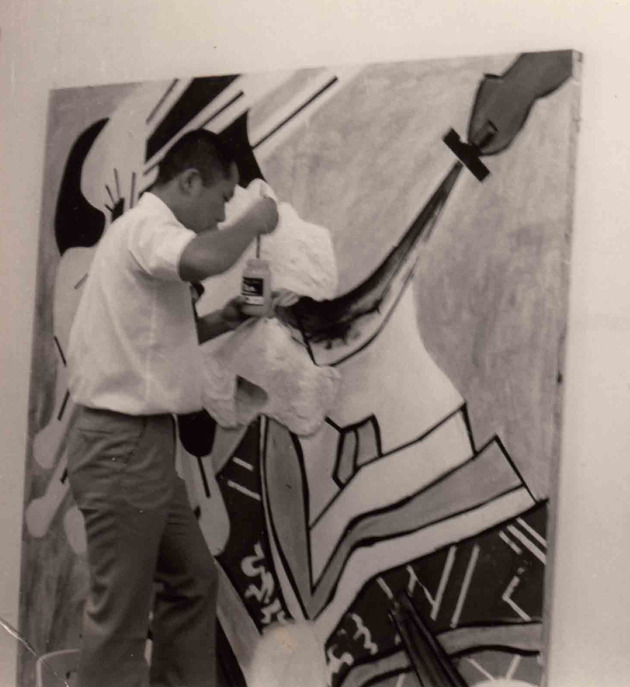

Making “Bloody” Oiran

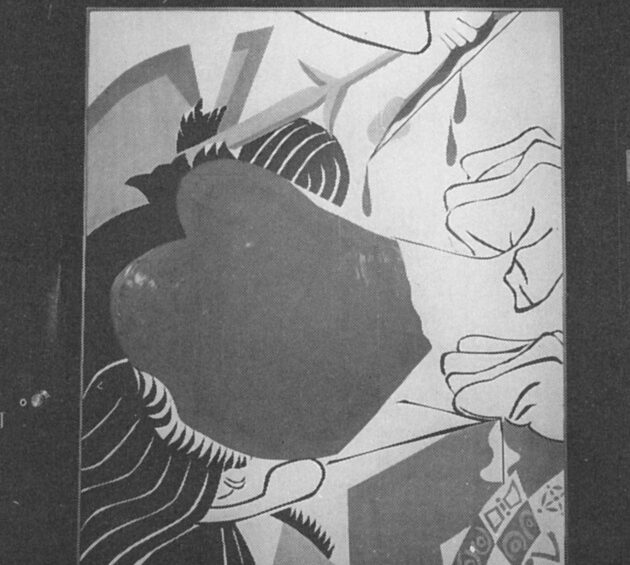

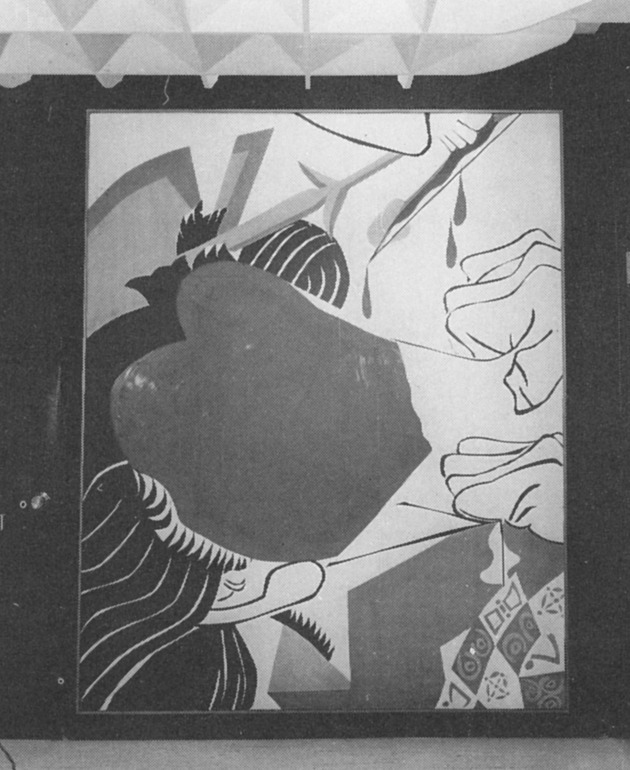

Shinohara developed this mode of mechanical production as the Oiran series unfolded over six months. For instance, as the surviving photograph shows (fig. 13), in the no longer extant Murder of Oiran, exhibited at Naiqua Gallery in October 1965, Shinohara hand painted an oiran’s head being chopped off by a sword in crude lines with a brush, while using plaster to cover her face. At the end of that year, Shinohara rendered the same motif with pink metal foil in the background and white plastic for an oiran’s face; the work was a finalist in the annual juried exhibition at the Contemporary Art Museum in Nagaoka (fig. 14). Then, in Peeling Off Face Skin, shown at Tokyo Gallery, Shinohara achieved a more precise and exact line in fashioning an oiran’s head by using a stencil and masking tape and attaching a piece of clear, bright red plastic over the red-painted face (fig. 15). The motif was borrowed from a Yoshitoshi print showing the famous criminal Naosuke Gonbei peeling off a victim’s skin in order to obfuscate his identity (fig. 16). Changing the victim to an oiran and the setting to a brothel, Shinohara used mechanical means to represent the scene in a sharp, clear-cut Pop style that showed few, if any, traces of the artist’s hand. Although the work does not survive today, the garish color of the painting, along with the blood-dripping sword, must have had a striking effect. Hyūga Akiko, one of the very few female critics in Japan then, praised the exhibition as a “festival in the color of women’s blood” that was “extremely beautiful and superbly gorgeous.”24Hyūga Akiko, Onna no chi no iro no matsuri: Shinohara Ushio koten (Festival in the color of women’s blood: Shinohara Ushio solo exhibition), Nihon dokusho shinbun, March 28, 1966, p. 10.

In terms of iconography, Shinohara’s exhibition was clearly at odds with the traditional doll festival. First of all, the hina dolls portraying the emperor and empress—a motif inspired by the classical Japanese dolls that his mother crafted for a living—were enlarged to life-size and had aluminum boxlike bodies. While Shinohara conflated the empress with an oiran by adorning her head with a gaudy kanzashi, he gave her companion an even wilder treatment: when a switch was turned on, the figure’s head rotated at a high speed, driven by an electric motor inside, which emitted a tremendous noise. Shinohara further complicated the iconography with representations of women from diverse times and social classes, including a Heian (9th–12th century) princess and an Edo komachi (a beautiful daughter of a townsman). Even more sensational was the exhibition’s sexual overtone, represented by two paintings: one, depicting a pair of phalluses, and the other, a couple making love, inspired by erotic ukiyo-e. This wide array of female types depicted in the show suggests that for Shinohara, the series was not just about oiran per se but about a female archetype of olden Japan, which he created through conflating various images of women.

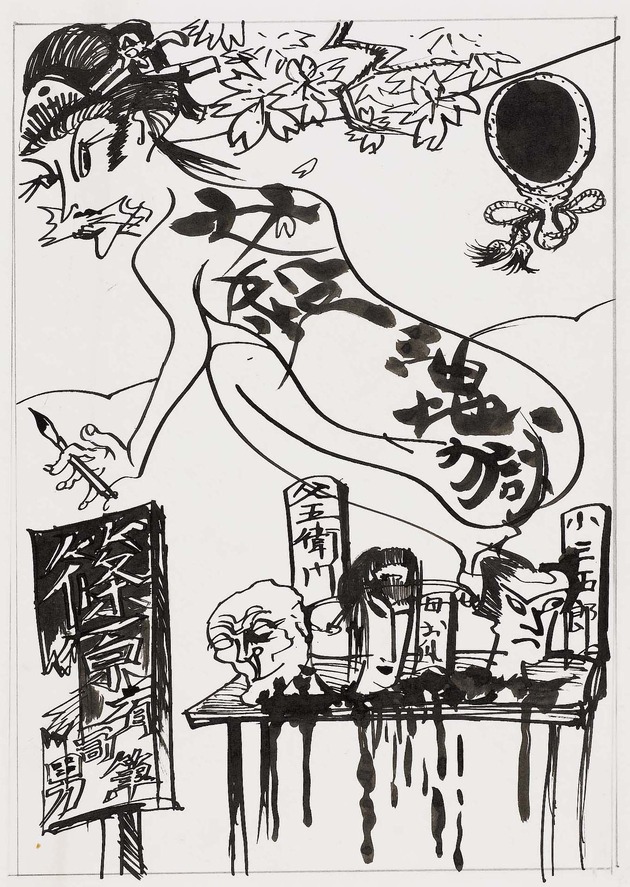

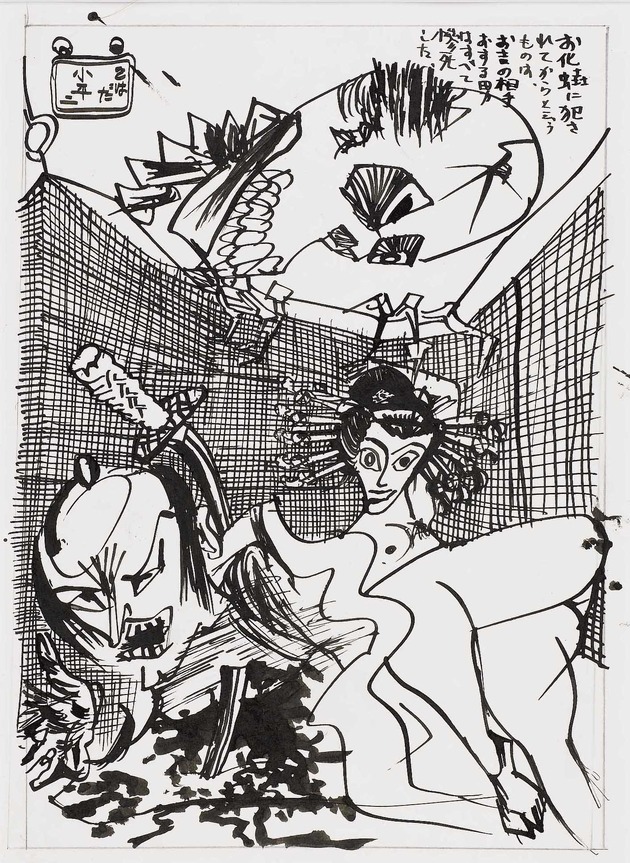

A key to understanding this iconographical conflation is Shinohara’s Okichi Story, a set of illustrations he executed in 1965 with his virtuoso draftsmanship, and intended for an artist’s book (fig. 17). The series derives from another inspiration Shinohara found at the time: bunraku, the Edo-era puppet play, and its popular repertoire, The Woman Killer and the Hell of Oil, which he saw on TV. The play is particularly famous for its over-the-top murder scene in which Okichi, the beautiful wife of an oil vendor, is killed, in an accidentally spilled pool of oil, by Yohei, the adopted prodigal son of another oil vendor. In the original story, there is no sexual relationship between Okichi and Yohei, despite the suggestive murder scene in oil and blood. However, in Shinohara’s adaptation, Okichi is an oil vendor’s daughter, touted as a komachi for her exceptional beauty, and has sex with her admirer on their first date. During their lovemaking, Okichi is raped by Monster Frog and transforms into a cursed oiran, complete with an oiran hairdo. In her fate following this ghastly rape, “every man she made love to was violently murdered,” as Shinohara annotated in one of the scenes (fig. 18). Thus, the artist conflated images of komachi and oiran in his story, establishing his own icon of “Oiran.”

In Doll Festival, a scene of Okichi’s lovemaking by the irises reappeared, with the jealous Monster Frog hovering overhead to hint at an imminent atrocity (fig. 19). In other works, too, Shinohara extended this narrative-inspired approach to depict women in various settings, drawing from numerous inspirations. This rather complex “celebration” of women is more aptly articulated in the exhibition’s Japanese title, Onna no matsuri, or “Women’s Festival,” than in the English title “Doll Festival,” which denotes the childlike innocence of a “girls’ festival.” Under the Japanese title, Shinohara portrayed women in drama-infused images evolved from prototypes in Yoshitoshi and late-Edo erotica. By creating ukiyo-e–inspired works with modern mechanical methods, Shinohara devised a perfect foundation for his image-making, recasting late Edo muzan-e into what can be called “Pop ukiyo-e” or “Bloody Pop.” 25The critic Ōshima Tatsuo praised the series as “Shōwa ukiyo-e” in “Onna no matsuri: Shinohara Ushio ten” (Doll festival: Ushio Shinohara exhibition), _Sansai (April 1966), p. 83.

Many critics recognized Shinohara’s breakthrough achievement with Doll Festival. In addition to Hyūga Akiko, Miki Tamon hailed the artist’s “unprecedented maturity of style” in his review,26Miki Tamon, “Geppyō” (Monthly review), Bijutsu techō, no. 267 (May 1966), p. 127. which, unusual for that time, was accompanied by a full-page color reproduction of an installation view of the exhibition (fig. 20). Despite the show’s critical success, however, the reality for Shinohara was tough. None of the works from the show sold, and Shinohara was disappointed by the silence of the influential “Big Three” critics—that is, Tōno Yoshiaki, Nakahara Yūsuke, and Haryū Ichirō. Furthermore, because the show yielded no profit, the gallery demanded that that the artist pay for exhibition expenses.27Oral History Interview with Shinohara, February 13, 2009. Unable to pay the bill, Shinohara gave Doll Festival, a major piece in the exhibition, to the gallery.28The work is now in the collection of Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art in Kobe. If critical success and artistic maturity were still not enough for Shinohara to make a living as an artist in Japan, the only thing left for him to do was to move to New York, his long-held dream that had been frustrated in 1964. To explore the possibility, Shinohara wrote to Porter McCray, director of The JDR 3rd Fund, whom he had met in Tokyo the previous year.29Shinohara, letter to Porter McCray, June 7, 1966, Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, New York. ACC 96: 121, Box 151, Folder Ushio Shinohara, P & S/JPN/B-6935. After three years, he was finally awarded a yearlong fellowship and left Tokyo for New York in May 1969 to begin a new chapter in his long career, which continues to this day.

For the extended version of this essay, please see chapter four of Hiroko Ikegami’s The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2010). See also “Shinohara Pops! When Oiran Rides a Motorcycle, Wonder Woman Swings a Samurai Sword,” in Hiroko Ikegami and Reiko Tomii, Shinohara Pops! The Avant-Garde Road (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2012), pp. 10–25.

- 1With its no-jury, no-prize policy, Yomiuri Independent Exhibition, held by the Yomiuri Newspaper company from 1949 to 1963, presented an annual occasion for young artists to exhibit anything they created.

- 2The Neo Dada group in Japan was founded in Tokyo in 1960 and was active for about six months. Its representative members included Yoshimura Masanobu, Shinohara Ushio, Akasegawa Genpei, and Arakawa Shūsaku.

- 3Shinohara Ushio, Zen’ei no michi (Avant-garde road), (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 1968).

- 4Tōno Yoshiaki, “Kyōki to sukyandaru: Katayaburi no sekai no shinjin tachi” (Madness and scandal: Fanastic new faces of the world), Geijutsu shinchō 10, no. 11 (November 1959), pp. 104–112.

- 5Tōno Yoshiaki, “Robāto Raushenbāgu arui wa Nyū yōku no ‘Jigoku hen’” (Robert Rauschenberg, or the New York inferno), Mizue, no. 683 (February 1962), pp. 42–56.

- 6Shinohara’s autobiography was originally titled The Road to the Avant-Garde. The name was changed to Avant-Garde Road when it was published as a book in 1968.

- 7Shinohara, Avant-Garde Road, p. 118.

- 8Ibid., p. 131.

- 9Shinohara Ushio, “Coca-Cola Plan Episode,” an unpublished statement prepared for the exhibition Shūzo Takiguchi: Drifting Objects on Dream, held at Toyama Prefectural Hall Museum, 2001.

- 10Shinohara Ushio, interview with the author, July 3, 2003, Brooklyn.

- 11Quoted in Miyakawa Atsushi, “Anti-Art: Its Descent to the Everyday,” Bijutshu techō, no. 234 (April 1964), p. 49.

- 12Kuwabara [Sumio], “American Artists, No. 4: Rauschenberg—Elegant Culprit of Pop Art,” Tokyo shinbun, July 29, 1963.

- 13Shinohara, Avant-Garde Road, pp. 142–43.

- 14Shinohara Ushio, interview with the author, July 3, 2003, Brooklyn.

- 15Ibid.

- 16The journal has not been identified. Shinohara recalls that it was a home décor magazine, not an art journal.

- 17Homi K. Bhaba, Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), p. 86.

- 18Shinohara, Avant-Garde Road, p. 185.

- 19Yoshitoshi’s series was created in collaboration with Ochiai Yoshiiku. They created fourteen prints each, and Yoshitoshi selected especially bloody scenes.

- 20Shinohara, in Dōru fesutibaru/Doll Festival: Onna no matsuri (Women’s festival), exh. cat. (Tokyo: Tokyo Gallery, 1966), unpaginated.

- 21Ibid.

- 22Oral History Interview with Ushio Shinohara, conducted by Hiroko Ikegami and Reiko Tomii, February 13, 2009, Oral History Archives of Japanese Art. http://www.oralarthistory.org/archives/shinohara_ushio/interview_02.php

- 23Shinohara, telephone conversation with the author, June 29, 2012.

- 24Hyūga Akiko, Onna no chi no iro no matsuri: Shinohara Ushio koten (Festival in the color of women’s blood: Shinohara Ushio solo exhibition), Nihon dokusho shinbun, March 28, 1966, p. 10.

- 25The critic Ōshima Tatsuo praised the series as “Shōwa ukiyo-e” in “Onna no matsuri: Shinohara Ushio ten” (Doll festival: Ushio Shinohara exhibition), _Sansai (April 1966), p. 83.

- 26Miki Tamon, “Geppyō” (Monthly review), Bijutsu techō, no. 267 (May 1966), p. 127.

- 27Oral History Interview with Shinohara, February 13, 2009.

- 28The work is now in the collection of Hyogo Prefectural Museum of Art in Kobe.

- 29Shinohara, letter to Porter McCray, June 7, 1966, Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow, New York. ACC 96: 121, Box 151, Folder Ushio Shinohara, P & S/JPN/B-6935.