In this segment of the theme “Global Conceptualism Reconsidered,” the curators of the exhibition Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s reflect upon their experiences organizing the exhibition. They address in the following interviews the origins of the exhibition’s concept, the challenges faced in defining and presenting the variety of conceptualisms across the exhibition’s many international subsections, and how their work on this exhibition affected their later projects.

The interviews were conducted via email. post asked Reiko Tomii, co-curator of the exhibition’s Japan section, to respond to the following questions in 500 to 1,000 words.

1. What was your role in Global Conceptualism? How did you get involved in the exhibition?

I was a section co-curator for Japan, together with Dr. Chiba Shigeo. While working for my PhD at the University of Texas at Austin, my primary area of study was postwar American art. By the time I completed my dissertation in 1988, I was in love with American Conceptual Art. Then, working at the Center for International Contemporary Art (CICA) from 1988 to 1992 and collaborating with Alexandra Munroe on the publication of Japanese Art After 1945: Scream Against the Sky (1994), I received intense exposure to postwar Japanese art. I came to recognize that the radical experimentalism of Japanese conceptualism, along with performance, installation, and land art of 1960s Japan, often far exceeded that of their American counterparts. It was a major “eureka” moment for me, and I decided to concentrate my efforts on post-1945 Japanese art. In the fall of 1994, I received a letter from Jane Farver asking me to recommend a curator to work on the Japanese section of Global Conceptualism. Delighted with the fortuitous timing, I nominated myself.

2. How did you reconcile the exhibition’s curatorial agenda with your own definitions of conceptual art in Global Conceptualism? How did the main components of conceptual art in Japan differ from their counterparts in the US?

The exhibition’s agenda was to decenter the narrative of conceptualism to reflect its global diversity, while my goal was to place Japanese conceptualism, which was unique in its local development, internationally relevant, and full of historical implications, in a world history of conceptualism. These two goals formed the two sides of a coin, perfectly in sync.

Although American Conceptual Art is usually characterized by its strong analytical tendency and its emphasis on language, what enthralled me about it was its use of institutional critique and the potential this offered for social engagement. This understanding was nurtured by my reading for comps and was partly encouraged by the art discourse of 1970s Japan, which was also steeped in seido hihan (literally “institutional critique”). When I received Jane’s letter, I knew that other Japanese curators would stick to the linguistic and analytical aspects of Japanese conceptualism (for instance, Matsuzawa Yutaka’s use of language), which was the standard narrative at the time and had been strongly colored by the Japanese reception of Euro-American Conceptual Art. Global Conceptualism afforded me an opportunity to put forth my view of decentering. I am grateful that Jane took me on at a time when I had had little curatorial experience.

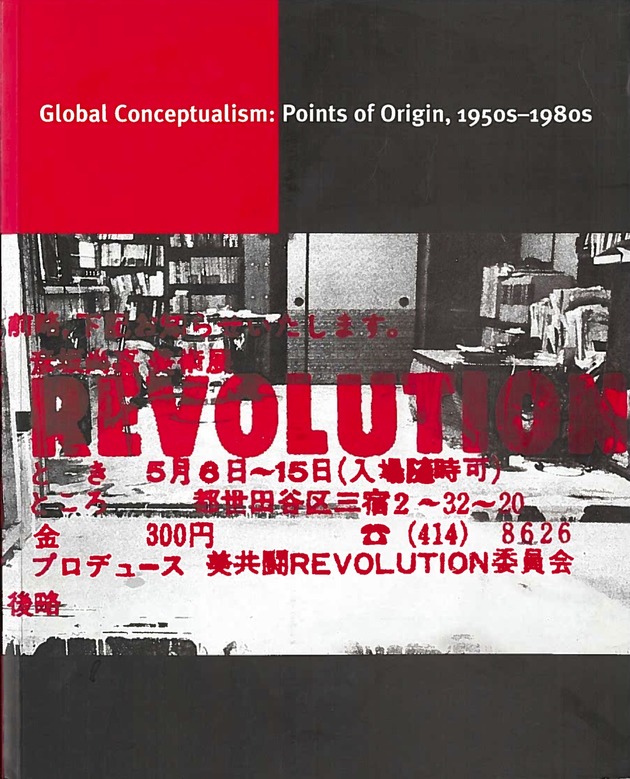

Since the curatorial parameters that were first established were rather limited in scope–five artists were to be included in each of the show’s ten sections–my initial idea was to highlight the institutional critique aspect with a focused look at “exhibition experiments” by key Japanese conceptualists. The projects I intended to present were Matsuzawa Yutaka’s Anti-Civilization Exhibition (1965), Akasegawa Genpei’s Courtroom Exhibition Event (1966), Bikyōtō Revolution Committee’s solo exhibition series interrogating international institutions (1971) and their pact not to make or exhibit art (1974), and a series of participatory situations devised by Kashihara Etsutomu under the title of Exhibition (early 1970s). This plan was subsequently expanded to examine a full range of institutional issues, from painting to authorship to system. Jane always encouraged me to think bigger. Since my curatorial agenda inherently encompassed the reevaluation of American Conceptual Art, the two of us often discussed this question along with two other project leaders, Rachel Weiss and Luis Camnitzer.

3. How has the notion of Conceptual art changed since then, in Japan as well as in New York?

The Euro-American notion of Conceptual Art and its Japanese transplant, Gainen geijutsu, were a dominant ideology back then, and it resists change even under the pressure of globalization today. A careful art-historical reassessment is necessary, which I have attempted in my book Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (MIT Press, Spring 2016).

4. How did your curatorial idea for Conceptualism echo (or not) in other sections in Global Conceptualism?

One of the major contributions of Global Conceptualism was its presentation of concrete, local examples—“object lessons”—that demonstrated the ubiquity and contemporaneity of the first phase conceptualism (1950s–1960s). I myself found it truly liberating to be able to call attention to the local specific aspects of conceptualism in 1960s Japan, following its internal logic. I saw the same thing happen in other sections: the exhibition presented solid local knowledge. There was indeed a lot to learn.

The challenge was how to consolidate these disparate parts, and it is understandable that critics faulted the exhibition’s region-by-region presentation for being fragmentary. An irony of the exhibition was that it successfully decentered the center-periphery narrative of conceptualism by taking the shared idea of conceptualism as its starting point and demonstrating the multiplicity and diversity of its local manifestations. Alas, it stopped short of regrouping them, say, by putting together similar examples from different regions. However, “regrouping” is a relatively new idea only recently tackled in museum exhibitions and in word art history. It should be noted that the practice of regrouping has its own hazards, one of which is that one is content with making a facile juxtaposition of works and failing to go no deeper than the surface. This leaves us without knowledge of individual local developments that inform each locale’s practice. Perhaps, given its physicality, the exhibition format makes it difficult to create multilayered and multivalent readings. For those to occur, there must be a clear methodological footing.

5. Could you share some of your memories of Jane Farver?

I will always remember the forward-looking vision Jane held of non-Western contemporary art. This made her an early contributor to the globalization of art. For example, she gave first U.S. solo museum exhibitions to Yanagi Yukinori (The World Flag Ant Farm and Wandering Position: Project—Red, White and Blue at Lehman College Art Gallery, New York, 1990) and Cai Guo-Qiang (Cultural Melting Bath, Queens Museum of Art, New York 1997), literally launching their global careers. Global Conceptualism could not have been realized without such an open vision underscored by her conviction and sympathy for the under-recognized. She was an early supporter and a frequent collaborator of mine. It was my good fortune to know her early in my career, since Global Conceptualism compelled me to consider methodologies for linking the global and the local in meaningful ways. The exhibition has remained a point of reference that I have returned to time and again; in a sense, how to “improve” it became an art-historical challenge for me. The idea of regrouping and a methodological proposal I put forth in Radicalism in the Wilderness came out of this reflection. About ten days before her passing, I telephoned Jane to discuss this particular point, as I was writing about it in the epilogue of the book. I am saddened that she has gone before the book is published, but my consolation is that she kindly read an early draft of the epilogue in the midst of the “crazy” (her word) preparations for Venice, and she knew the progress I had made since Global Conceptualism.