Drawn primarily from the SAC journal published at the Sogetsu Art Center, this growing list presents original source documents in Japanese along with English translations. They offer insight into the issues and debates that circulated among artists and critics involved in experimental art, film, and music in 1960s Japan. You can continue to develop this list by adding your own links, readings, and annotations in the Discussion section.

Source contents

Contemporary Music and Performance

By Ichiyanagi Toshi, 1963

Publisher: Sogetsu Art Center

Language: Japanese

Today’s performance world is in imminent danger of spiritual collapse. This is a global trend that stems from the beginning of the twentieth century, when the reproductive arts began to lose their way. By now, they have lost their meaning. Music, too, has been reduced to a ghost of its former self. The flamboyant manner in which so many concerts are currently performed leaves me with a sense of total emptiness. Musicians have become little more than the salarymen of music; the performers lack a music of their own. The majority of them seem to be engaged in music only out of sheer force of habit. I cannot imagine that this style of performing, lacking as it is in independence, can be sustained much longer. It is, after all, an unbalanced form of music that divides creativity and performance. This is an unbearable situation for musicians with any backbone, and it is being broken down all over the world by a small group of people with new ideas. But the majority of musicians maintain a sentimental attachment to the old musical mold.

Until the beginning of the twentieth century, contemporary music played a vigorous spiritual role. The era in which the so-called virtuoso exercised his authority and performed vibrantly by trusting his own feelings marked the apex of reproductive music. After that, performers allowed themselves to be subjected to a miserable set of conditions. As they came to accept the ironclad rule that performance follows creation, they were abandoned by historical change and deserted by music.

As society became ever more industrialized, music was rationalized, and emotion and empathy were banished from performance. With its origins in Schoenberg’s work, music cleaved ever more closely to its underlying mathematical structure, and as it grew increasingly elaborate, its performance required the utmost in rigorous precision. In contrast to performance conventions of the past, which allowed for emotion and sensitivity, the new music demanded performances founded on rigid logic. But, content with the style of the past, performers did not actively attempt to make this new music their own. They approached it with the reproductive spirit that was rooted in retrogressive classical and romantic music. Thus, performance succumbed to mannerism. The gap between performer and composer widened, and the gulf between contemporary music and its audience deepened. At this point in time, when reproductive music has completely lost its meaning, what exactly is performance? And how should it be conducted?

I believe that without merging performance and the creative act, music exists only as a form. In the past, musical creativity and performance were clearly separate: performers produced the sounds, but they did not play their own music. It is necessary for performers to free themselves from this wrestling match with other people’s music. They must refuse these engagements, which are devoid of autonomy and akin to reciting someone else’s texts. The slight differences in intonation that distinguish one performance from another no longer have any meaning. Such performances represent the kind of uninspired repetition that can be entrusted to machines. In music based on indeterminacy, sounds are not predetermined, and performers are given a place to explore their inner potential. In this new type of performance, in which such an exploration is expressed as a musical act, performers are liberated from their subsidiary role of the past.

The twentieth century was marked by wars, revolution, the atomic bombs, massive labor strikes, and more. Each of these cataclysmic events encouraged people to question their values and join the struggle for freedom. The creative arts, too, underwent a variety of changes in response to such events, and old conventions were quickly cast aside. In light of this history of quick responsiveness to changing times, it is incomprehensible that today’s performers sit with their legs crossed beneath the protective shield of reproducible art. The important creative developments that occurred in music during the twentieth century are inseparable from performance. Through the invention of the tape recorder and the emergence of electronic music, for instance, composers were able to create sound using only a machine. Music could be made and heard without the medium of performance, provoking serious discussions about the redundancy of the performer. But even when performance was challenged in this way, performers themselves reacted with indifference, if at all. As long as performance is forced to follow in the wake of creativity, the performative realm will continue to degenerate. The only hope lies in the emergence of a type of performer with the ability to integrate and at the same time guide the composer. It is perfectly obvious that there is a need for a revolution in performance.

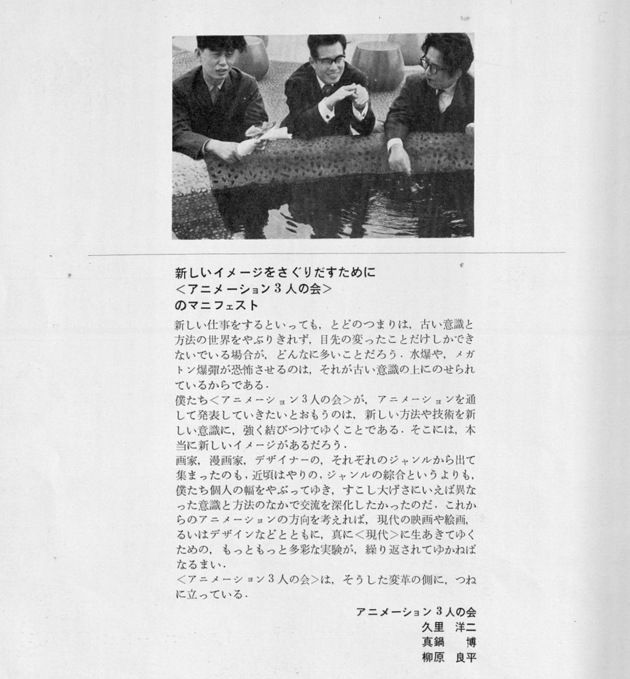

The Three-Person Animation Manifesto: Toward the Creation of New Images

By Kuri Yoji, Manabe Hiroshi, and Yanagihara Ryohei, 1960

Publisher: Sogetsu Art Center

Language: Japanese

How often do we see someone who boldly sets out to do something completely new succeed in making only superficial changes because they are unable to break free of established thought patterns and methods? It is because of our enslavement to old ways of thinking that we live in fear of the atom bomb and the hydrogen bomb.

New processes and technologies must go hand in hand with new modes of consciousness. Therein lies the path to the creation of truly new images. This is what we, the Three-Person Animation Circle, want to achieve through animation.

We have come together from separate disciplines — painting, cartooning, and design — not to create just another popular cross-media collaboration, but to transcend our own personal boundaries, to add a new dimension to our interactions by exploring different processes and modes of consciousness. For animation to evolve and stay truly contemporary, there is a need for much bolder and more varied experimentation, such as those we see today in the fields of live-action film, painting, and design.

We, the Three-Person Animation Circle, will always question convention and stand firmly on the side of innovation.

Three-Person Animation Circle Kuri Yoji Manabe Hiroshi Yanag

Kuri Yoji, Manabe Hiroshi, and Yanagihara Ryohei

Originally published in Sogetsu Art Center Journal 7, October 1960. Translated into English by Colin Smith

Three Animators

By Tanikawa Shuntaro, 1960

Publisher: Sogetsu Art Center

Language: Japanese

anima [æ’nimə] n. ([Latin—life, breath]) Soul, spirit.

animal [æ’niməl] n. An organism of the kingdom Animalia; generally has motility and must ingest other living things to survive. animate [æ’nimeit] vt. To give life or vitality to something; to encourage or inspire.

animation [œniméiʃən] n. Vigor, vitality. animato [à:nimá:tou] a. ([It]) [music] Lively. animator [æ’nimeitə] n. A person or thing that imparts life or vitality; (an artist who produces animated films)

*

Allow me to introduce three gentlemen: Kuri Yoji, Yanagihara Ryohei, and Manabe Hiroshi. The general public knows them as cartoonists. In fact, however, they are animators, in the sense of “people that impart life or vitality.”

*

Kuri Yoji looks on first sight like a typical family man. Around ten years ago, there weren’t more than six grains of rice in his rice bin, but today he is a self-made man who runs his own film studio. He also produces COO, his own comic magazine, which has released four issues so far.

*

Yanagihara Ryohei has the look of a salaryman. In fact he is a salaryman, and makes no apologies for it. His animated commercials for Kotobukiya, however, are brimming with woe and grotesquerie. He doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who gets drunk on cheap liquor like the Torys Whisky his work sells.

*

Manabe Hiroshi is a devoted husband and father, and with his partner—a devoted wife and strict mother—by his side, his home life is the very picture of happiness. Whatever venom he secretes is channeled into his visually assaultive artwork. Truly a soto-Benkei. Anyone who views his work and does not find a reflection of him- or herself in it would best be advised to move to Texas.

*

Kuri Yoji is a feminist. It’s only fitting that he has a daughter, and she is one of his sources of inspiration, for which she commands her share of the rations. However, despite being a paterfamilias, Yoji is also adept at weaving erotic tales, like his “XX’s X” which I recently read in XXX magazine, a really first-rate piece of work brimming with wit and refinement. Some guys never grow up…

*

Yanagihara Ryohei is…well, to tell the truth, I’ve only met him two or three times, perhaps not enough to tell you what he is. I can tell you, though, that his Pikaro jii-san comic strip in the Asahi Shimbun newspaper leaves me wanting more. Rather than the works of subtle malevolence he’s creating now, I’d like to see him producing works of out-and-out malevolence.

*

Manabe Hiroshi recently bought a car. According to Manabe, “The era in which poets tell stories through words alone, and painters tell stories through pictures alone, is long past. I animate my pictures, and by doing so I animate myself as well.” This is marvelous, just as long as it doesn’t lead to reckless driving.

*

It is no concern of mine whether the three of them are friends, merely business partners, or for that matter, locked in a love triangle. What’s important is that they form a gallery of rogues, each having his own bitingly distinct flavor, not merely collaborators teaming up because three heads are better than one. I have no doubt they’ll generate new visions that transcend the narrow boundaries of cartooning.

*

All life begins with the simple act of movement. Not movement governed by outside forces, but movement from within the self. It is this spontaneous movement that gives meaning to life. I believe the task of an animator is not just to break down movement into segments. The task of an animator is to take segmented, freeze-frame movement and find a way to unite it into a single, emotionally gripping whole.

*

An amoeba splits and reproduces itself, a solitary tiger pounces, a little girl shrinks in sudden bashfulness. I would like to see animation that rivals the beauty pervading each of these, the myriad movements that make up the living world.

On Improvised Music as Automatism

By Tone Yasunao, 1960

Publisher: 20-seiki Buyo 5

Language: Japanese

In May of 1960, our group chanced upon an absolutely new experiment in music. It was an improvisational piece of musique concrète, executed collectively.

Just before discovering this approach, we had been preparing materials for a tape recording of musique concrète. A variety of sound sources stood before us, including oil drums, washtubs, water pitchers, brooms, plates, coat hangers, metal and wooden dolls, a vacuum cleaner, stones from the game of Go, cups, a radio, an illustrated guide to plants, a wall clock, cello, rubber ball, an alto saxophone, a prepared piano, etc. Once we started the tape rolling, the smorgasbord of sound-producing objects struck us with a bizarre and vivid sonic image. We then began improvising with absolute spontaneity. What followed was a profusion of sounds which usually go unnoticed or are produced only out of necessity during day-to-day life. We lost ourselves in the movements and collisions of the objects, and suddenly we felt as if we had a grasp on the life force of the unconscious, materialized.

After performing this first musical experiment, we immediately noticed that our working method was analogous to the famous definition of Surrealism found in the first Surrealist manifesto: “Pure psychic automatism by which it is intended to express, either verbally or in writing, the true function of thought. Thought dictated in the absence of all control exerted by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations.”

Energized by this discovery, we decided to continue experimenting. This led to our second piece, Automatisme No. 1.

I believe our work with musical automatism represented an important departure from previous works of musique concrète for two reasons. First, six of us produced it collectively; and second, we adopted improvisation within the framework of musique concrète, recording the actual sound without any mechanical manipulation so as to maintain the purity of the spontaneous method.

The collective nature of our music was a means of circumventing subjectivity, personal idiosyncrasies, conventional thought patterns, and other residues of humanism that can plague solo attempts at automatism. Like the first work of automatism, Philippe Soupault and Andre Breton’s book Les Champs Magnétiques (The Magnetic Fields), ours was a collaborative effort that sought to draw forth our respective unconscious minds in order to attain a universal automatism, to reach the collective unconscious that, according to Jung, underlies each personal unconscious.

As for our process of pure automatism, it was not merely an improvised musical performance, but rather a spontaneous performance based on a wide range of concrete sounds. It served as a rebuttal of Tono Yoshiaki’s critique of pure automatism as seen in the work of Joan Miró: “A sort of spineless subjectivity seems to pervade his pure automatist works. The weak point of pure automatism is that it is short on rapport with the properties of materials, frequently descending into mere decoration.”

Having arrived at this method of making music, we aspire to show you the objet sonore (sound object) in its true form, in which degrees of transparency and opacity, dampness and hardness reverberate within a storm of immediacy, charged with raw power, and make the concrete music works of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry sound, by comparison, like the pallid song of a nightingale.

The Current Status of John Cage

By Tono Yoshiaki, 1960

Publisher: Sogetsu Art Center Journal

Language: Japanese

John Cage is recognized as the most uniquely talented American avant-garde musician. Last year, during Cage’s concert (?) [sic] tour of Europe, I attended a performance at Galerie 22, an avant-garde gallery in Düsseldorf, Germany, of a strange dissonant work using his trademark technique of inserting pieces of wood between the piano strings.

One Sunday in New York, I also heard a piano composition titled Winter Music at a place called the Village Gate, an underground bar in Greenwich Village. It was performed along with Poème électronique, a tape piece that Edgar Varèse made for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. Winter Music is another odd work that one might say focuses on the pleasure of sound, including the spaces between sounds and silence. The performer would tap the piano strings with a wooden mallet and then stop. Then he would use a key to make a twang and let the sound die down. As things continued in a similar vein, it was strange to watch New Yorkers in the bustling jazz metropolis enjoying these huge gaps in sound. The composition was dedicated to Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. These two artists have recently come to be called Neo-Dadaists. The former coldly depicts almost nothing but American flags and numbers in beeswax, while the latter makes daring assemblages consisting of things like a stuffed goat with a tire around it.

The relationship between Johns, Rauschenberg, and Cage is oddly (?) [sic] close, and there is a fundamental affinity in this new field between Cage’s unusual scores that resemble abstract paintings and Johns’s number series. In addition, according to a recent letter, the two artists are apparently designing the stage sets for a modern ballet with music by Cage. The two records Cage has released have also proved to be popular. One is from a concert at Town Hall last year that included all of his works from the last twenty-five years, and the other, titled Indeterminacy: New Aspects of Form in Instrumental and Electronic Music, contains a lengthy recitation of ninety humorous stories accompanied by music. On another occasion, Cage brought a bathtub, toaster, motor, piano, and a goldfish bowl into a TV studio and performed a bizarre brand of concrete music for half an hour, leaving the veteran host amazed and dumbfounded.

Originally published in Sogetsu Art Center Journal 2, April 1960. Translated into English by Christopher Stephens

Community of Image: An Examination of Environments in Art

By Takahiko Iimura, 1969

Publication: Kikan Film

Publisher: FILM ART

Language: Japanese

Media and Identity

In the summer of 1967, the hippie filmmaker Ray Wisniewski asked me to shoot some footage. When I asked what it was he wanted shot, he told me just to bring my camera and we’d take it from there. Puzzled, I brought along my camera on the appointed day, and he gave me some film and told me to go out and film people in the vicinity in any manner I pleased. This was in the neighborhood they used to call the Far East, the slums to the east of my own neighborhood, the East Village. It was a jungle, the streets littered with trash and dog turds, ravaged buildings abandoned and left to deteriorate. I recalled that a hippie had been murdered nearby at one point.

I wasn’t altogether unfamiliar with the area. I had visited it a few times, and filmmakers I knew lived there. When I went out on the street and started to film, right away kids came up and said, “Hey, film me, man,” and wouldn’t go away. I went inside an apartment building, where I found elderly people and children in a room with crumbling plaster walls lit by a bare bulb. The bright light mercilessly illuminated the grubby interior. Far from being embarrassed by the camera, though, they pointed out a place where the wall had crumbled and told me to get that on film.

The neighborhood was an enclave of immigrants—Puerto Rican, Jewish, Polish and so forth—a ghetto very far removed from the trim, tidy Main Street of middle-class Caucasian America. The film I shot that day was material for an art “environment” to be held on that city block. This environment was a large-scale multimedia event, incorporating tens of thousands of feet of film, countless slides and tapes, and a live band. It was an environment in the true sense of the word, created by and for the local community.

The participants were filmmakers, artists and other neighborhood residents. They took photos and shot film while they themselves were being photographed and filmed by other people. Several giant makeshift screens made from bedsheets sewn together hung from buildings, and quite a number of projectors were placed in windows and ran simultaneously. The band played raucous rock music while children shouted and jeered delightedly. They were excited when they found their own faces on the screens. It was raw, practically unedited footage, with slides overlaid randomly and projected on screens that fluttered in the wind. The street was jammed with people, some of whom were dancing. Everything and everyone that had been filmed and photographed was shown to the subjects themselves, in their own environment. This simultaneous viewing and being viewed was a feedback loop of the residents’ identity. The projection environment was ideal for this endeavor.

The budget for the event came from a local fund for community projects, but it was not enough. A lot of cameras, projectors, and screens were provided free of charge by local artists and residents. Andy Warhol had already filmed himself and his surroundings and then screened the unedited footage as a cinematic environment, but this block party environment was done on a larger scale. The footage of the local people ran on and on, and the event lasted from early evening until deep into the night.

An exploration of identity and the self was carried out in a more sophisticated manner in Marta Minujín’s Minucode. At a party in an art gallery, she mounted cameras on the walls and filmed a segment of the party from various angles, then started projecting the footage from the same points it had been shot from. There were now life-sized projections of people on three walls. The camera had recorded them faithfully (although when the results were played back, the same person appeared three times, from three angles, on three different surfaces.) During the playback, the silhouettes of the flesh-and-blood people watching the footage synced up with the projected people on the walls. In this peculiar, immersive environment, not only were the viewers and the viewed one and the same, they were also synchronized, and the actual, physical people seemed to become shadows while the ghostly, colored images in the film became real people. Multiple identities overlap. The very faithfulness with which the film medium records reality poses questions about what the act of recording means. The coordination of filmed subjects and played-back footage in both time (length of time) and space (size) assigns identity not only to the human subjects but also to the medium itself.

Environments and Multiple Screens

The two events I have just described are prime examples of environments with multi-screen projections. I have given these examples in order to combat the tendency to appreciate contemporary multi-screen and cinema-environment works for their stylistic and technical aspects alone, or the tendency to confine visual-display media to the realm of design alone (although in fact there is no definable distinction between design and art.) Of course you are free to interpret the two examples I have given above any way you wish, but I myself think about the first example primarily in terms of environment, and the second primarily in terms of multi-screen projection.

Both terms could be applied to both of the art projects, but in the first example, the word “environment” can be used in its literal sense to describe a local society or community. In Japanese cities, it could be said that people do not form communities (with the exception of groups like the Neighborhood Associations during World War II), or that the city is beginning to replace the fading paradigm of the rural community. In cities of the United States, however, a community mentality remains strong. This collective spirit operates in a manner that is both progressive and reactionary. For example, on the one hand, black people tend to be shut out of white communities (reactionary) while, on the other hand, the Black Power movement actively calls for the creation of black communities under black control (progressive). Meanwhile, hippies in the East Village have clamored for the liberation of a local commercial theater on behalf of the community, and managed to obtain a free “community day” at the theater.

The street environment described in the first example above was also largely the work of hippies. In that case, the simultaneous use of all available materials in an environmental fashion was a very natural way for them to operate. After all, this is the way that everyday life is lived, and a community is a group of people who are individuals and at the same time a collective, sharing the same segment of time and space. When there is no temporal or spatial hierarchy, and especially in a racially mixed milieu like that of the East Village, a street environment like that described above is simultaneously highly diverse and clearly illustrative of the community’s image. It represents the people’s desire for identity. If an environment is rooted in a sense of community, that environment will be presented in a way that reflects the essence of that community, and the images it incorporates will be those that the community members all share. The street environment I described at the beginning was an archetypal example of this expression of a community’s image (the global community in the Stan VanDerBeek “Movie-Drome” illustrates the same phenomenon on a larger scale.)

The multi-screen work by Marta Minujín, the second example, entails multiple views of the same space projected on multiple screens, synchronized so as to coalesce as a single idea. Projection of footage of a single space shot from various angles on multiple screens is not unique to this piece: another example is the Disney production Canada, screened at Expo 67 in Montreal. The work, projected on a circular screen, showed a 360-degree panoramic view of the Canadian landscape shot by nine cameras. The projectors were positioned in the interstices between screens so as to recreate the 360-degree panorama. The audience viewed this panoramic landscape from the center, encircled by screens, but at all times they were directed to face one of the multiple screens, and their movements were thus restricted. This is because most of the footage consisted of moving shots. Rather than capitalizing on the multifaceted nature of the images, the viewing guidelines stand in the way of a simultaneous group experience of the film. An environment is meant to be fluid and all-encompassing, with “forward” and “backward” not fixed but interchangeable. The significance of multiple screens is that they share the same space at the same time. Imposing a guideline to the viewing process of such works would be to merely another attempt at forcing the viewer to adhere to cinematic rules found in entertainment cinema. Almost all of the multi-screen projections at Expo 67, including the Czech Laterna Magika, were geared toward entertainment in this way.

What differentiates Minujín’s multi-screen work from entertainment of this sort is her posing of questions about aspects of reality that arise through the multi-screen medium. In this case it is necessary to equate multiple screens with multiple projections, with the synchronization of projections being key to the total image environment that encompasses the entire room. However, multiple projections do not necessarily mean multiple screens, as demonstrated by films like Warhol’s ★★★★ (Four Stars, 1967), which features multiple overlaid projections on a single screen. That film derives impact from the temporal disjuncture caused by multiple images projected on top of one another.

Intermedia in Film

There are many names for the new phenomena that are currently emerging in the art and cinema worlds. Some of the broad categories are intermedia, mixed media, environments, expanded cinema (or art), projection art, multi-screen, and multi-projection. Some of these terms indicate modes of expression, while others are technical terms, and in many instances they overlap. In any case, none of them fit neatly within conventional categories, all push the boundaries, and all seem to have a kind of inevitability. While time-honored art forms such as film or painting, in and of themselves, will not fade away, these new media make the very classification of art according to medium seem outdated. The future may bring works that can only be labeled broadly as “art,” by which point art may have become indistinguishable from life.

This evolutionary step, which encompasses all art forms, is the greatest leap forward since art was first divided into multiple art forms. In the process of integration, each art form retains its intrinsic independence, rather than being patched together from various others. Within the various art forms, intermediate or hybrid mediums are not necessarily something new. In recent times, Happenings played a key role in their emergence in the early 1960s. Environments can be seen as preceding, following, or overlapping with Happenings. Kinetic and light art are intertwined with these genres as well. As stated earlier, art forms overlap, and a single work can be both light art and an environment at the same time.

Since the 1950s, artists in music and dance, such as John Cage and Merce Cunningham, have been propelling intermedia forward. More recently, the incorporation of technology into art by Group E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) has received much acclaim. The above examples roughly belong to the category of 1960s American art, but what I must point out here is that interpreting these changes as linear and chronological would be a serious error. Hasty critics tend to oversimplify by saying that Happenings came first and gave way to Environments (or Intermedia), but in fact Happenings continue to evolve today.

Here I would like to share my thoughts on the progression from movies or films (including slides) to intermedia built around moving images, including televised ones, based on what I have seen firsthand. Like Happenings, intermedia shows are often one-off affairs. Even if they are repeated, they change with each staging, and it is rare to see a work that takes a fixed form like a conventional film. When such works do exist they are usually big-budget productions, automated and computer-controlled like those of Expo 67. Even leisure and entertainment facilities like the Electric Circus1Electric Circus was a dischotheque located in East Village, Manhattan. Opened in 1967, Electric Circus was where The Velvet Underground and Andy Warhol presented the “Exploding Plastic Inevitable.” feature electronic automation, though they retain some manual elements.

Prominent artists in the field of intermedia (or expanded cinema) who use film include Stan VanDerBeek, USCO (a technological media art collective) and Robert Whitman. Other well known names are the ONCE Group in Michigan, Milton Cohen, and Robert Blossom, who combines live acting with recorded film in his performance Film Stage. Earlier on, there was John Cage’s 1952 performance incorporating film at Black Mountain College2John Cage staged what has been considered the first happening to incorporate multiple mediums called Theatre Piece No. 1 at the Black Mountain College in the summer of 1952. Films and slide projections by Tim LaFarge and Nick Cernovich were a part of a presentation that included theatre, dance, music, painting, poetry, photography and film. and Allan Kaprow’s 18 Happenings in Six Parts in 1959, the title of which is widely regarded as the origin of the term “Happening.” Experiments such as these have been underway for many years.

The various intermedia works that incorporate film can be roughly divided into two categories. One of them fuses film with live acting or props, and the other consists solely of two-dimensional images such as film, slides, and television. Practitioners of the former include Whitman, Cohen and Blossom, as well as a great many Happening creators and dancers (Ken Dewey, Robert Rauschenberg, Kenneth King, Meredith Monk, Carolee Schneemann, Alex Hay) and musicians (La Monte Young, et al.). Among the exponents of the latter are Stan VanDerBeek and USCO as well as Aldo Tambellini, Jackie Cassen, Rudi Stern, Ben Van Meter, Don Snyder, Marta Minujín, Ken Jacobs, Andy Warhol, Matsumoto Toshio, and myself. However, these two categories are not mutually exclusive. There are numerous examples of collaborations between image-creators and live performers, such as the joint intermedia project undertaken by Cage, Cunningham, and VanDerBeek.3Variations V, presented at Philharmonic Hall in New York, 1965. In some cases engineers also work closely with artists. Intermedia inevitably gives rise to new forms of collaboration between artists working in different media.

Rather than being led by a single director, the projects are based on the premise of each participant presenting 100 percent of what he or she has to offer. In many cases there is no preliminary discussion before the work is presented to an audience. Live projections without human performers often go beyond the projection of two-dimensional images to incorporate lamps, strobes and various unique projection devices. Unlike light sculptures, they rely on the projection of light for effect. Luminous objects such as neon art works do not fall into this category.

Works involving the projection of pure light can be further divided into two categories. In the first, projected light itself is the means of expression; in the other, shadows create meaning. The former is exemplified by the work of Nicolas Schöffer, and the latter by Thomas Wilfred. One example of Schöffer’s work is an enormous tower equipped with a specially designed reflective plate that casts light in all directions when a light beam is projected onto it. Another piece that represents the projection of light is a performance by Forrest Myers that I saw in a park in New York’s Greenwich Village. Gigantic searchlights beamed light into the night sky without the use of reflective devices like as in Schöffer’s work. The beams of light themselves were the art work.

Thomas Wilfred’s work, in the collection at MoMA (The Museum of Modern Art), involves a screen onto which smoke-like, multicolored light from a specially designed reflective device is projected at regular intervals. Another example is the work of Earl Reiback, who replaces the screen with a light box. Also, the filmmaker Robert Breer has fitted a projector into a screen box and showed his own animated abstractions in a gallery. Tony Conrad’s stroboscopic film The Flicker turns the projector into a source of light minus the usual images. This is a case of approaching light art from the perspective of film. Others, such as Jackie Cassen and Don Snyder, have projected light through materials other than film, such as glass vessels or glass plates onto which oil, paint, or ink are dropped. Psychedelic projection art makes liberal use of such techniques, and they are an indispensable element of light shows at venues like the Electric Circus and the Fillmore East. These are just a few of examples of the commercial applications of projection art.

As we have seen, when light itself is the focus of a work, the significance of projection art is in the act of projection itself rather than in the contents of the two-dimensional images presented on film or slides. In some cases, the image projected is simply a medium in and of itself.

Aspects of Multiple Projection

Multi-screen projections are one kind of projection art, a category of multi-media incorporating filmed images. In projection art, film may be used in intermedia works paired with live acting, but while the character of individual works may differ, the difference, in the end, between film by itself and film paired with live action is nothing more than a difference of approach. The distinction between the two is merely a matter of convenience. While keeping this fact in mind, if we compare the two we find they have a mutual influence on one another. Unless it is truly fully automated, projection contains an element of human performance, with no two projections exactly alike. This is a crucial distinction between projection art and conventional film projection. Until now, filmmakers were involved with their work until it was in the can, but they took no responsibility for its screening. As an expressive medium, film becomes visible only when it is screened and it is only then that it communicates to the viewer. It is the right of the filmmaker to play an active role in screening his/her work, and there is absolutely no reason for commercial agents to have control over the film. In the mainstream film world, producers of independent films have little choice but to relinquish the rights of their films to distributors with capital; films that are independently produced are not necessarily independently screened. By contrast, as we shall discuss later, intermedia projection art actively seeks viewer participation, seeking to create a community through the agency of the motion picture medium.

On the one hand, in the case of intermedia utilizing film, the presence of recorded images juxtaposed with live performances introduces an extension of the “site-space” of an environment, which creates a larger environment than the site-specific environments of Happenings. You could say that the presence of film brings an entirely new dimension to such environments.

Multi-screen and mixed projections are sometimes interpreted as extensions of conventional film. In such cases multiplicity and multidimensionality are handled according to existing cinematic rules. For example, at the Montreal Expo, the multiplicity, or the unity (integration) of the multiple screens, was performed almost completely according to guidelines prepared in advance. The montage was basically governed by an orthodox cinematic grammar and arranged on multiple supports. In the same genre, however, there were notable works at the Expo, such as the National Film Board of Canada’s Labyrinth, which featured movie screens placed on top of each other and mirrors used to multiply a single image in a virtually infinite kaleidoscope, as well as the Czech works Polyvision and Polyekran, which featured a mosaic of screen boxes that moved forward and backward while images were projected on them.

Some multi-screen works depart completely from orthodox cinematic grammar (in particular, that of the montage technique). In Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, two films are shown side by side on a split screen, seemingly unrelated yet generating serendipity. In Film in Which There Appear Edge Lettering, Sprocket Holes, Dirt Particles, Etc., George Landow loops an off-centered image so that it appears doubled on one half of the screen while the elements described in the title appear on the other half. Also, in a recent multiple projection event by USCO at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a motorized revolving column in the center of the room equipped with twenty slide projectors flashed images around the gallery. The beauty of the piece was that each individual projector flashed a single image, but as the projectors rotated, the image appeared in a different place at every flash, in a way that tested the intellect. Another innovative idea is explored in Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome, a structure in which film is projected on the inner surface of a hemispherical dome. Rather than appearing across a series of discrete screens, as in a flat multi-screen projection, the film becomes a cosmic collage where the borders between images are blurred. In Les Levine’s work featuring multiple TV sets scattered across an environment, images are played back on videotaped loops in a highly mechanical manner. In contrast with conventional television broadcasting, which uses montage to make TV flow smoothly, like film, Levine lays bare the essentially mechanical nature of TV as a medium. Aldo Tambellini is another artist who mixes television and film. And Marta Minujín, who I mentioned at the beginning, is an excellent example of an artist who eschews montage in favor of multiple screens that create a single, enveloping cinematic environment.

Part 1 of 2. Originally published in Kikan Film, 1969. Translated into English by Colin Smith.

Special Report!: Seismic Rumbles from the Underground

By Iimura Takahiko, 1966

Publisher: Eiga Hyoron

Language: Japanese

Iimura Takahiko reports from the United States that the rumbles in underground art are growing in intensity in a manner that nobody could have predicted. The expansion of media—so-called intermedia—has led to a radical transformation of the movie theater, and Stan VanDerBeek has established a theater named Tabernacle in a former church.4Tabernacle was the name of the USCO performance, as indicated later in the article. WE may assume that this is an editor’s error.The time for cinematic revolution has come!

Iimura Takahiko

Part of this year’s New York Film Festival is a special program on independent cinema, combining film screenings and lectures in a series lasting for all ten days of the festival. This is a landmark event demonstrating that independent cinema, also known as underground cinema, has claimed its civil rights. (It’s certainly the first time independent cinema has been represented on this scale in a venue like Lincoln Center.) Meanwhile, for the main events of the Festival itself, the American offerings do not include a single new Hollywood film. What the programs offer instead are silent films, such as Clarence Brown’s A Woman of Affairs (1928) and Cecil B. DeMille’s The Cheat (1915); newer works, such as the independently produced American New Left film The Troublemaker (directed by Theodore J. Flicker); and the independent short Oh Dem Watermelons (Robert Nelson), which also has been screened recently in Japan as an opening feature. The big draws this year, however, are four Czech films; French cinema, such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Masculin féminin and Pierrot le Fou, Alain Resnais’s La guerre est finie, and Robert Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar; and Luis Buñuel’s Simon of the Desert. The only Japanese picture presented is The Burmese Harp, directed by Ichikawa Kon and made ten years ago.

According to the newspaper, there were no Hollywood films because the organizers refused to screen them. Whatever the reason, the result is a major promotion of the independent and underground film scene. The festival is a big annual event for cinema in the United States although, to tell you the truth, I was too busy watching the independent films to get around to the main features. The independent films are the ones that interest me in any case.

An independent film series does not necessarily bring together the most prominent works of the genre, although, at this stage, of course, it is difficult to say which works should be assigned such a status. While we may say that the underground has claimed its civil rights, this is merely a journalistic viewpoint, as it goes without saying that the films themselves couldn’t care less about their civil acceptance. The point is that films in the independent or underground category have gained a status they used to lack, much in the way that Marcel Duchamp’s urinal entitled Fountain was once scoffed at but is now considered a landmark work of art.

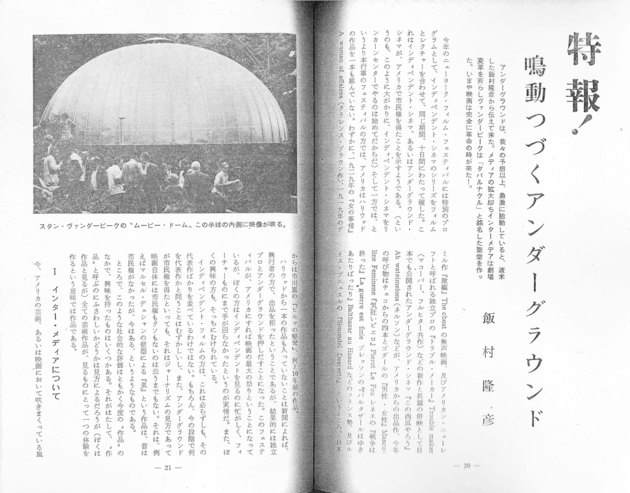

I Intermedia

One new wave in the storm of contemporary American art and film is that of intermedia, also known as expanded cinema. As these names suggest, it is the expansion, combination, or, dare I say, the copulation of media. It can take the form of an environment or an experience. One manifestation of this trend is the migration out of the theater to claim territory for screening films in the world at large. I refer, in part, to Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome, a hemispherical dome fifteen meters in diameter. VanDerBeek is known in Japan for his 1959 animated collage film Science Friction, shown there in 1965, made with pictures cut out and pasted from magazines such as Life (incidentally, in the U.S., the straightforward term “combine” is preferred to the vaguer “collage,” which has its origins in Surrealism.) The comical, often satirical film features automobiles, giant women, the president of the United States and other things transforming into rockets that fly around. I haven’t seen any of VanDerBeek’s other films, but apparently he has gone on to create more such “combine” animations. Evidently he has a sustained interest in this particular genre.

In fact, what happens in the Movie-Drome could also be understood as a “combine.” Certainly one could say that VanDerBeek has taken the “combine” methods he used previously within the rectangular frames of films and expanded them into the Movie-Drome’s hemispherical dome. Five or six film projectors, four slide projectors, and lights beamed through patterned or cut glass are placed inside the dome. The films and slides include home movies, newsreels, VanDerBeek’s own films, snapshots, scientific photographs of plants and classic paintings and are all simultaneously projected, either intermittently flashing or continuously spooling through the projectors. The audience lies on the floor to watch the show. The project is not yet completed, and it is not clear when or if it ever will be completed, but it works to create a maelstrom of chaotic imagery. Unbound from the flat surface of the conventional movie screen, the imagery envelops the audience. It has claimed the entire space as its territory.

This screening environment is outside the bounds of independent cinema, and it was built in a suitably fringe environment of a clearing in the woods in a rural area a two-hour drive from New York. VanDerBeek built a hut beside it to live in. When I visited the Movie-Drome it was being unveiled to the public for the first time, and even VanDerBeek said he had never seen it in full action. The dome is an entirely new experiment, a vessel that could potentially contain any and all images, and it seems his main intention in building it was to create a new projection environment, a unified microcosmos. Eventually, however, the mass-produced projection equipment he is currently using will have to be modified or replaced. Here, after all, projection is an art form, a performance unto itself, and projectionists are required to rise to the level of artists. For VanDerBeek, in charge of the entire space, the act of projection and the projected images oscillate between being divisible and indivisible as the audience mediates between being aware of and oblivious to the act of projection. Evidently his interest currently lies in the performative aspects of the work, and it is certainly true that changes in the performance methods bring about changes in the entire image-space. Personally I hope that rather than introducing some sort of order to this performance, he maintains the chaotic nature of the images while exploring the possibilities of creating new kinds of image-spaces.

To quote VanDerBeek from his article “Culture: Intercom and Expanded Cinema, A Proposal and a Manifesto” for the magazine Film Culture:

This vision concerns the immediate use of motion pictures . . . or expanded cinema, as a tool for world communication . . . and opens the future of what I like to call “Ethos-Cinema.” Motion pictures may be the most important tool for world communication. At this moment motion pictures are the art form of our time. We are on the verge of a new world / new technology / a new art. When artists shall deal with the world as a work of art. When we shall make motion pictures into an emotional experience tool that shall move art and life closer together. All this is about to happen. And it is not a second too soon. We are on the verge of a new world, new technologies, new arts.5VanDerBeek, Stan (1966). ‘Culture Intercom, A Proposal and Manifesto,’ Film Culture, 40: 15-18.

At times VanDerBeek refers to his dome as an “image library” or a “life theater.” In short, it is a venue in which the past and present experiences of humankind, on a global scale, are simultaneously depicted in a wide variety of image media. At the same time, it is a laboratory for the development of a non-verbal, international visual language as a means of offering new perspectives on the future of humanity. Motion pictures constitute the fundamental tool in this endeavor.

One might recognize a certain naïveté in VanDerBeek’s optimistic faith in the “world,” “technologies,” and “the arts,” but his outlook also stems from the sober recognition that, even in the 20th century, humankind has not yet found a common language that promotes understanding across national borders. From the same article, VanDerBeek says, “The world hangs by a thread of verbs and nouns. Language and culture-semantics are as explosive as nuclear energy.” Simply put, he wants to create a visual vocabulary that can replace the international language of nuclear threat.

One thing is clear: to Stan VanDerBeek, the roles of artist and inventor are two sides of the same coin.

II USCO’s Psychedelic Tabernacle6Another editing error mistakenly identifies the Psychedelic Tabernacle as a performance by Stan VanDerBeek and mistitles the chapter “VanDerBeek and the Psychedelic Tabernacle.” We have taken the liberty of correcting this here.

At first glance it appeared to be a wood-frame country church just like any other in a rural community. When I entered, I did not know what to expect.

The show had already begun by the time I entered. It was daytime but the interior was dark, as all the curtains had been drawn. Strange music—Indian Buddhist devotional music—played in the background. The incongruity of Buddhist devotional music in a Christian church struck me. Another oddity was the pentagonal chamber erected in the center of the church, with a circumference of fourteen or fifteen meters and a diameter of four or five meters. The building was a hemispherical dome with a white screen stretched across it. The “congregation” removed their shoes, as is customary in Japan, before entering the chamber. It was the first time I had seen such a thing in the United States. Rugs were spread on the floor, and in the center was a mushroom-shaped, tin-plated fountain about two meters high with water coming out of it. It reminded me of a Buddhist water-drawing ceremony, albeit an automated version. On all five walls of the chamber were murals with abstract patterns of concentric circles, human forms, and so forth arranged in a manner reminiscent of tribal art. There were speakers on all five walls, with the sound emerging from each of them out of sync in a way that seemed to rotate progressively around the chamber. Lying on the floor in cramped conditions (there was no choice about that) I looked up and saw slides and films projected on the white domed screen overhead. The images were projected from outside the chamber, and the projection was electronically programmed, with no one resembling a performer in sight. (By contrast, at his Movie-Drome, VanDerBeek mingled with the audience, and there were five or six projectionists at work, causing the images to multiply suddenly, expand or overlap.) The images included landscapes, human faces, abstract patterns and the sun, and seemed to have been carefully selected. Mounted here and there on the walls were colored light bulbs, which also flashed on an off automatically. My eyes were drawn to the words “Peace,” “Love,” and other slogans inscribed on the enclosure around the fountain, which glowed, reflecting the light from the light bulbs.

During the hour or so that I spent lying there, time seemed to stand still. It only took about ten minutes to understand how the system worked. After that the presentation seemed to become repetitive.

The strange space, the Psychedelic Tabernacle, was a collaborative project by USCO, a media art collective of ten or more artists—poets, painters, film directors, and others—and engineers. Incidentally, according to the dictionary, the meanings of the word “tabernacle” include: a tent sanctuary used by the Israelites during the Exodus; a house of worship for religious dissenters; a physical body serving as a temporary residence for the spirit; and a tomb with a canopy. It is not hard to see why USCO selected this word for the environment they had created.

According to one member of USCO with whom I spoke, the Psychedelic Tabernacle was established not for a specific religion, such as Christianity or Buddhism, but rather to enshrine a sort of abstract sanctity or universal humanity. Certainly, there were no crucifixes or Buddhist statues in the building. The tabernacle seemed intended to amplify a certain wavelength of consciousness. To this end USCO have deployed all manner of media, film, painting, music, sound, light and language, fusing them together in the service of an abstract ideology.

However, it is difficult to pinpoint just what this abstract ideology might be. The tabernacle is an environmental and experiential gestalt. Taken to its logical conclusion, it might become a worldwide network of “houses of worship for religious dissenters,” or 20th-century houses of worship for the increasingly secular contemporary human. It could be called electronically automated art-as-religion, but it is certainly not religious art in the manner of medieval paintings of Jesus Christ. When I say art-as-religion, I might as well say religion-as-art. Either way, the important thing is that USCO is seeking to break free from stereotypical notions of what both art and religion are about and to create a particular kind of mental and spiritual environment; they have attempted to concoct a “white magic” ritual for the 20th century. The group of a dozen or so artists and technicians have collaborated to create a harmonious “house of worship” in their 20th-century tabernacle.

III The Encircling Universe of Robert Whitman

Just after I had come back from a one-day bus trip (Agnès Varda, who was in the U.S. to promote her new film Les créatures, and Andy Warhol were also on the bus), I caught one of Robert Whitman’s “theater pieces” that was presented toward the tail end of the festival. Whitman has been active primarily in Happenings and has been turning Happenings into a form of multimedia theater in a month-long series of “theater happenings” that he stages in a Greenwich Village theater during the summer.

The piece I saw only lasted about an hour, but it was a stunning illustration of what is possible in the field of intermedia and expanded cinema. While the two previous examples, the work of VanDerBeek and USCO, focused on the creation of a unique theater-space, Whitman arranged his performance in an ordinary theater. And while VanDerBeek and USCO pursued similar missions, though the former spoke of an “image library” and the latter of a “tabernacle,” Whitman is not advocating any particular idea for his performance. Of course, a work of art is always independent of the artist’s ideas, and one should avoid the pitfall of taking the artist’s ideas as a starting point for interpreting the work. (I mention this partly because in the U.S. it is rare for an artist to set forth a particular idea and become known for that idea, or turn it into the focus of his or her artistic activities.)

With this in mind, what sets Whitman apart from VanDerBeek and USCO is the clarity of the images (or the calculations) in his work. Whitman, like the others, is engaged in using all manner of media in a multifaceted manner and even engages with what we could call an Environment. However, he is not merely delivering multifaceted images but instead has developed a methodology for intermedia to become a unique means of self-expression. Of course, we are not here to pass value judgments on his work against the other performances we have discussed. For VanDerBeek, images are materials for building an all-enveloping space, a universe if you will—the dome being a private universe— a place of fusion, coupling, and encirclement. Meanwhile, for Whitman, intermedia is the layering and disassociation of consciousness in a multidimensional environment. His media pieces are flexible, as they can be staged in any theater and do not require a specific, customized space.

At the theater piece I attended,7The performance Iimura attended is Two Holes of Water, Part 2, which was presented at Lincoln Center. the first thing that one encountered was a pair of curved copper plates on either side of the entrance. The attendees’ distorted reflections on the surfaces of the plates were captured by a video recorder and projected on a wall inside the venue. Audience members spent some time looking at the image feed of people who came into the space after them, no doubt imagining what their own reflections might have looked like. After a while a film was projected on another wall, consisting of two superimposed images of a woman. In one image, she was seen from the front, and in the other, from behind. The woman undressed and then dressed again, and the overlapping images made it appear as though her breasts were on her back, and so forth. At the same time, films of the South Pole and slides of penguins were projected on the ceiling. Meanwhile, a film of a woman was projected on the curtains on stage, and the woman shown in the film appeared live in front of the curtains, performing the same actions that she performed in the film. The simple actions included standing up and lying down. On the other side of the stage, a piece of white fabric inflated into a large balloon-like form that pushed against the ceiling and forwards toward the audience. A film was projected onto the fabric, and the images in the film stretched out like the balloon. Meanwhile, the feed from the video recorder showed unsuspecting passersby outside the theater and footage of a woman putting on her socks (this was probably a performance) in close-up. The soundtrack consisted of frog calls and at times the sound of water. When we heard the sound of water, a film showing water was projected on the curtains. Both sides of the theater, the ceiling, and the curtains on the stage were all used as projection surfaces and the back wall was the only surface left untouched. When the performance ended, the images and sounds gradually receded like a tidal wave, and I have no clear memory of the curtain closing. What I found particularly interesting was the film projected on a giant ballooning cloth and the moment when it protruded outwards toward the audience, giving the image a physical substance. For the most part, Whitman’s work deals with images as reproductions: a film of a person and that same live person appearing together; the image of myself that I was not able to see, but that would have been captured and projected using the video system; the images of others that I was able to watch concurrently as they were being recorded; and the front and back of the same person projected, aligned and overlapping, onto a single surface. Only the giant balloon-like form with images projected onto it transformed into an actual object. In fact, the physical existence of the balloon was highlighted by the reproduced images.

One could say that for Whitman, the “media” in intermedia has a clear function as an artistic tool. He has turned his command of images into a methodology that allows him to manipulate the chance occurrences in Happenings to a desired effect. I can assume he used the same methods to entertaining effect at his other events in his summer series (as I did not see these, I cannot say for sure).

Overall, the fascinating thing about intermedia is its imaginative use of various media in a way that destroys preordained spatial and temporal restrictions imposed onto the medium. Of course, it would be difficult for us to say that these works are created in a new medium, since already existent media forms, including slide and moving-image projectors, are being used as part of the process. Instead, intermedia, is the intersection of different media, and part of what makes it interesting is the way these intersections willfully ignore the inherent grammar of each individual medium. The Dionysian celebration triggered when one medium violates another medium is also part of intermedia. Perhaps historically, artists have been too faithful in following the dictates of their chosen mediums. Although they might have thought that they dominated and controlled their medium, in fact, it was the medium that controlled them, and their self-expression was dependent on the validity of a particular medium. In film in particular, subservience to the mechanical aspects of the medium has meant that approaches to cinema have been defined by these mechanical limitations. It seems quite clear that the time has come for us to recognize these mechanical attributes for what they are, as limitations.

Naturally, intermedia will not replace the cinema as we know it. (It is impossible to predict such things, and in any case I am not particularly interested in mere changes of mechanism.) Intermedia is the discovery of a different type of space for images to inhabit. Incidentally, I have already written on the topic of images in theatrical space (Jikken no eiga ka, eiga no jikken ka [“Film as Experiment, or Experiment as Film?”], Eizo geijutsu (Film Arts) vol. 3).

IV Happenings as entertainment

I consider VanDerBeek’s multifaceted imagery, which is in some ways similar to Whitman’s use of multifaceted media, a form of “space drama” that develops a visual language, a new means of communication, that one might call an arrangement of space. While the images may be multifaceted, VanDerBeek’s images retain their integral meaning as images; however, he has turned the images into building blocks for the construction of an environment. Each block has its own unique dimensions that provide glimpses of an invisible drama. In any case, one could say that intermedia is currently in the experimental stage, an experiment without an end, and the inherent possibilities seem to be limitless.

Here I would like to quote a few words from Robert Whitman (extracted from the book Happenings edited by Michael Kirby). Although it is on the subject of Happenings and not necessarily intended to provide an explanation of intermedia, his words can help us understand the basic intentions behind intermedia:

The thing about the theatre that most interests me is that it takes time. Time for me is something material. I like to use it that way. It can be used in the same way as paint or plaster or any other material. It can describe other natural events. I intend for my works to be stories of physical experience and realistic, naturalistic descriptions of the physical world. Description is done in terms of experience. If somebody says something is red, then everybody knows what that means because they have seen it. They have had that experience. A story is a record of experience or the creation of experience in order to describe something. The story of something is its description, the way it got that way, its nature. The intention of these works has to do with either re-creating certain experiences that tell a story, or presenting experiences that tell a story, or showing them. You can re-create it or present it or show it. You can expose things. All these things have to do with making them available: you make them available to the observer, so called. (p. 134)

In conclusion, I would like to take a moment to recount my memory of a show at a discotheque that I attended soon after arriving in San Francisco. At this point intermedia seemed already to have been commercialized and turned into the medium for a sort of 20th-century religious ritual. This is common practice not only in San Francisco but in New York as well—there was a big report on the phenomenon in Life magazine just the other day. The event I attended was in a huge hall, with a band playing loud and intense rock music. The massive sound filled the space, which was packed with four or five hundred youngsters dancing wildly, wearing neon-bright colors, weird bell-bottom trousers, and clothes decorated with paint. On the walls a profusion of slides was projected in informel style (rather than ordinary slides, they were abstract pictures generated by kneading or splashing paint), in and out of synch with the music. Meanwhile, found footage, taken from old Westerns and newsreels, was projected in different directions, and the light show moved and pulsated at a frenetic pace. It went on for hours.

Intermedia was in full effect here, as the dance event incorporated not only rhythm and sound but also visual impact, incorporating multiple, diverse media. In situations like this, if we assume that auditory sensations are what move the body, it makes sense that visual stimuli have the strongest impact on the mind. Here the two were integrated seamlessly into a single environment. While intermedia was clearly utilized here for commercial purposes, it is not so clear which came first, intermedia as art or intermedia as commercial enterprise. It is like asking about the chicken and the egg. This confusion is illustrated best by Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable events featuring the Velvet Underground, but a discussion of Warhol will have to wait for another article.

Iimura Takahiko

Member of Film Independents

Originally published in Eiga Hyoron, 1966. Translated into English by Colin Smith.

Encounter with Unusual Films / Naiqua Cinematheque: Screening of 8mm Films, Iimura Takahiko Solo Cinema Showcase

By Obayashi Nobuhiko, 1963

Language: Japanese

■ Alight on the platform of Shinbashi Station in Tokyo, and the sizable banner of Naiqua Gallery comes into view. Much talked about for its bizarre name (“Naiqua” is a transliteration of the Japanese word for “internal medicine”) and ambitious experimentalism, the gallery is described by its head, Miyata Kunio, as “a test tube into which anything can be placed, which anyone can occupy . . . a transparent and neutral vessel for arbitrary use.” Having presented underground cinema screenings and sculpture exhibitions in the past, Naiqua Gallery has now established a regular experimental film series entitled Naiqua Cinematheque. There are high hopes for this series to resuscitate the amateur cinema world, which lately has been bogged down in an excess of films. Recently the first event in the series was held: a screening of the films of Iimura Takahiko, already familiar from the pages of this magazine.

■ Turned into an acronym, Naiqua Gallery becomes “NG.” These letters are inscribed in large, thick strokes at the entrance to the gallery. The films shown here are indeed, according to the conventional wisdom of the cinema world today, “NG” (No Good) films, outtakes at best. It seems the letters at the entrance are a bold declaration of Naiqua Cinematheque’s ambition to champion such films and ensure they receive the credit they deserve.

■ The event was well attended. After the screening a symposium was held for those too riveted by, or indignant about, what they had seen to drag themselves away. Here I would like to relate the content of that symposium. The program and the symposium participants, in the order their remarks were made, are as follows. I should note that parts of this article are fleshed out by my own reconstructions of the words spoken at the symposium.

■ Program

Kuzu (Junk) Music: Kosugi Takehisa

Dada ’62 Music: Tone Yasunao

Iro (Colors) Music: Tone Yasunao

De Sade Music: Machaut

6 x 6 Music: Takeda Akemichi

■ Symposium participants (in the order in which they spoke)

Hirata Sakio (Nichiei Science Film production manager)

Iimura Takahiko (creator of films shown at this screening)

Obayashi Nobuhiko (moderator / Eiga no Te no Kai [Filmmakers’ Association])

Takamatsu Jiro (artist)

Akasegawa Genpei (artist)

Satsuni To (novelist)

Oka Yoshiyuki (painter / member of Zenei Bijyutsu-kai [Avant-Garde Art Association])

Nagata Tomo’o

Oshima Tatsuo (film and art critic)

Takabayashi Yoichi (filmmaker) (88 mini-film pro)

■ August 10, 1963

■Symposium

Obayashi By the way, does anyone have opinions about any of the individual films? Like, “this part was interesting or this part wasn’t interesting,” that kind of thing?

Takamatsu De Sade was the most interesting. It was shot from just the right distance and there are a lot of interesting scenes, but then the camera starts to zoom in. Just when you want it to zoom in right on the center of the action the images become disjointed. That was interesting.

Akasegawa There was a lot that interested me besides the films themselves. The films themselves had a lot of problematic points when you compare them to something like Guernica (Alain Resnais, 1950), for example, but they were intriguing in principle. And I think only Mr. Iimura could have produced them. Like if you want to enlarge something in print, if you simply blow it up it turns all grainy, so you find another way to do it. But he insists on using precisely this technique.

Nagata Was that intentional?

Iimura It wasn’t especially intentional.

Akasegawa That’s what makes it interesting. That’s exactly what I’m talking about.

Satsuni What I find interesting is De Sade’s way of thinking. What makes it interesting is precisely the same thing that makes Iimura’s De Sade film interesting. Takamatsu I thought 6 x 6 was fresh. In particular its relationship to the distant past, or rather its lack of relationship, fascinated me.

Satsuni I wanted to see more of that kind of thing. That atmosphere that was reminiscent of a porn movie. Like the scenes in the apartment, those were good. But the best part was that bizarre sound.

Oka In 6 x 6, there’s that part where the man and woman come out carrying a box. What becomes of that?

Iimura That’s nothing in particular, it’s just a prop.

Oka I wanted to see more of that. I wondered what became of that box.

Nagata It would have been good to assign more meaning to that.

Satsuni There’s a Polish film with a scene where they come out of the sea carrying a wardrobe [Roman Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe (1958)].

Oka Later in the film they take the wardrobe back out to sea, don’t they?

Obayashi Right, the wardrobe is carried by two men.

Oka I wanted to know more about the role or the meaning of that box in Mr. Iimura’s film. Was it like, the stepladder turned into the crown, or something?

Takamatsu His camera angles were innovative. Sometimes the background was hidden by something in the foreground. We can’t see the whole picture, we can only see part of it. We get frustrated because we want to see everything that’s going on. There’s something ascetic about it. I also recalled that wardrobe scene from the Polish film, but Mr. Iimura’s aesthetic is different, it’s drier.

Nagata What was the music in De Sade?

Iimura That’s 14th-century sacred music by a composer named Machaut. I slowed the tape speed down. Yesterday I played it at normal speed, and in the past I’ve sped it up. I try to experiment with different approaches.

Akasegawa Slowing it down turns it into something melancholy, like a funeral dirge. It seems to take on a different meaning altogether.

Iimura They’re singing, but it sounds like some kind of monologue, doesn’t it?

Takamatsu It sounds like a nursery rhyme or something. And the music for 6 x 6 as well. That repeated chant of anonioigahananoanawoshigekisurutomodame —at first it sounds like nonsense, but then you realize it has a meaning, they’re saying ano nioi ga hana no ana o shigeki suru to mo dame, “when that smell hits my nostrils, I can’t stand it . . ” It goes from the sublime to the ridiculous.

Satsuni What were your intentions in the way you edited De Sade?

Iimura It’s supposed to be a morality play. But when you make a morality play the normal way it’s boring, so I tried to accentuate the vulgarity.

SatsuniIt didn’t look like a morality play to me. (laughs)

Oshima If you ask me, Mr. Iimura needs to slice up the footage he shoots, rethink the plotline and rearrange it before it can be called a film. If you just line things up sequentially, the camera remains extraneous to the action. If you just shoot footage and leave it as it is, without any vision internally tying it together, it won’t be transmuted into anything more than a series of images. Mr. Iimura obviously has something real that he wants to express, but the films appear to be simply a series of subjects filmed in sequence: a bald, no-frills presentation of realism, but the reality doesn’t experience any transformations. That’s a fatal flaw right there.

Takamatsu In the films of Antonioni, for example, there are long shots of scenery with nothing happening in them whatsoever. In a lot of cases it makes you feel just as if you’re inside one of the character’s heads, seeing through their eyes. Is that the kind of thing you’re talking about?

Oshima In those cases, the director is presenting houses or buildings as mere geometric patterns, but it becomes problematic when viewers realize that what they’re seeing is just geometry. The question is whether Mr. Iimura has the sense or the vision to capture objects in this way.

Takamatsu In a case like that, the objects are subjectively de-contextualized or alienated, what the French call dépaysement, but I think maybe in Iimura’s films they’re put through the same process in an objective rather than a subjective manner.

Nagata In Antonioni’s films I think the dépaysement is done intentionally. But with Mr. Iimura it’s unintentional, and that’s what makes the objects subjected to this dépaysement interesting.

Obayashi I guess from Mr. Iimura’s point of view, when Antonioni infuses some sort of meaning into a mundane landscape, some bland scenery with nothing in particular going on becomes a stand-in for the character’s mental landscape, and that’s a kind of calculation that takes the viewer for a ride psychologically, a kind of psychological trick. What’s interesting about Mr. Iimura’s films is that, carried to their logical extreme, we get films with neither a director nor a cameraman. We just get scenery with people doing things. And there’s a bare minimum of effort made to transform these psychologically into something else within the context of the film. In other words, there is minimum editing. That’s the way I understand it, and I have to say it’s an intriguing way to go about making films.

Iimura Like I said, my role is just to provide footage. All of us have hidden parts of our lives, and under normal circumstances we can’t watch other people going about their day-to-day private lives. So, in a film like 6 x 6, I shot footage of the daily life of a married couple without interfering and without manipulating the image with the camera or with editing. They aren’t putting on a show for the camera. If I came up with some contrivance in order to make it into a “film,” the whole thing would become a sham. Seeing a movie should be more than a visual experience, it should be a virtual experience.

Oshima Mr. Iimura, do you think of your films as stream-of-consciousness works or something like that?

Iimura No, I don’t.

Oshima Well, that’s a problem right there.

Takamatsu The subjectivity isn’t well-developed enough for them to be stream-of-consciousness.

Oshima If they aren’t stream-of-consciousness, if they’re just raw footage, then they end up as crap realism. They don’t look like automatism, not as it is described in the first Surrealist Manifesto. That’s where the problem comes in. If what Mr. Obayashi said about your films is correct then you’re on the right track, but I don’t think it is. I think, instead, that you’re pursuing the drama of life and death itself. And I think you’re right to take this direction. But it’s a challenge. Obayashi The way Mr. Oshima describes your direction and the way I was thinking of it are diametric opposites, but maybe that’s only fitting since you do have a lot of contradictions going on.

Oka It’s because the methodology is not well defined.

Obayashi Listening to you talk, Mr. Iimura, I thought that maybe stream-of-consciousness would be a good approach to take. When I’m talking to you normally, what you say only goes so far, and never actually gets around to answering the question at hand, don’t you agree? (laughs)

Iimura I think it’s good to talk about all kinds of different topics. I just don’t want to discuss film theory. (laughs)

Oshima In Dada ’62, you blur the focus by adjusting the projector while showing the film, or you zoom in so that the image overflows from the edges of the screen, or you stop the film, change the speed and so forth.

Iimura Tone Yasunao’s score for the soundtrack consists of various symbols written on a graph. I use these, interpreting them to adjust the focus and zoom and so forth. There’s an extra line added to the notation that represents the axis of time, and we follow that line when presenting the work.

Takamatsu That produced interesting effects.

Oshima The effects are interesting. But they don’t change the film itself, which is the core of the work, and that film itself is a weak one. When we hear Mr. Iimura’s explanation of the films, we can understand his intentions. His intentions are understandable, but the films themselves are a muddle. I think they’re basically flawed because the methodology isn’t defined. There are two problems: the power of the vision the filmmaker wants to express, and, how this vision is communicated to the viewer, in other words, its methodology.

Takamatsu Perhaps Mr. Iimura’s presenting his own daily existence to us is in itself a methodology.

Iimura I think shooting footage is enough for me. Rather than making movies, I think providing people with the raw footage and letting them interpret it is a faster way to arrive at where I’m trying to get to. For me to slice it up and re-edit it would be a waste of time. I provide the raw materials and each person is free to take it home and make of it what they wish. Everyone wants to encounter a vision when they go to see a film. If you want to be a visionary, go ahead, but I don’t think the filmmaker has a responsibility to fulfill that desire.

Akasegawa Perhaps I mean this in a different sense, but your films do seem to lack a sense of responsibility to the viewer.

Takamatsu Have you thought of collecting fragments of newsreels and making them into some kind of montage?

Iimura That is something I would like to try if I get an opportunity.

Obayashi I wonder what you would make out of them. After all, if you scrape together some discarded footage and make it into a basic film, in other words, edit it, you may come up against filmmaking issues like what Mr. Oshima has discussed and Matsumoto Toshio has before him—where within the time frame of the film to make what kind of cuts and how many, all these choices reflect the intentions of the filmmaker. That seems to go against the approach that you advocate.

Oshima That’s a problem, to be sure.

Kawani Maybe you could stuff a canister full of film scraps, then just thread those on to the projector. (laughs)

Oshima Yeah, you can start with whatever you happen to get your hands on. But then you still run up against the problem of making it into a montage.

Obayashi I wonder what Mr. Iimura would come up with in a situation like that. I’d like to see it. We’ve talked about it before, but it’s never gone beyond the talking stage.