Born in the village of Kwali, Ladi Dosei Kwali (1925–1984), the pioneering Nigerian potter, grew up in a family in which it was the norm for women to make pots for practical use and sustenance. Although it was customary for mothers to teach this skill to their daughters, Kwali learned pottery from her aunt. She soon excelled at hand-building in the Gbari traditional style and became renowned locally.1Gbari people, also referred to as Gbayi/Gwari, are Indigenous to the states of Niger, Kaduna, Kogi, and Plateau and to the Federal Capital Territory. Indeed, demand for her pottery grew, and various archival entries make reference to her work being sold beyond her hometown, in cities such as Minna in the neighboring state of Niger.2The papers of Michael Cardew, Crafts Study Centre Archives, University for the Creative Arts, GB 2941 MAC. Historical accounts also document that her pottery was known to sell out before it even arrived at the market.3E. Okunna, “Living through two pottery traditions and the story of an icon: Ladi Kwali,” Mgbakoigba: Journal of African Studies 1 (2012), https://www.ajol.info/index.php/mjas/article/view/117190. Ladi Kwali became an accomplished and widely celebrated potter due to her mastery of traditional pottery techniques passed down through matrilineal lines, which is a testament to her skill and dedication—and to that of the women in her community.

Her pottery’s forms and stylistic motifs were derived from Gbari culture and shared among women of her indigenous group (fig. 1). Kwali would go on to make hundreds of waterpots and other thrown wares featuring varied geometric and figurative designs inspired by nature, including animals and plants. This was a way for the artist to intentionally incorporate the Gbari design vernacular in earthenware and stoneware as she developed as a potter. The distinctive blend of traditional Indigenous Gbari pottery and British studio pottery represents Ladi Kwali’s shift from a local ceramist to an international one. This transition—influenced by cultural exchanges occurring in Nigeria when the country was still under British colonial rule—tainted the project with uneven power dynamics that, though problematic, shaped and defined Ladi Kwali’s global acclaim.

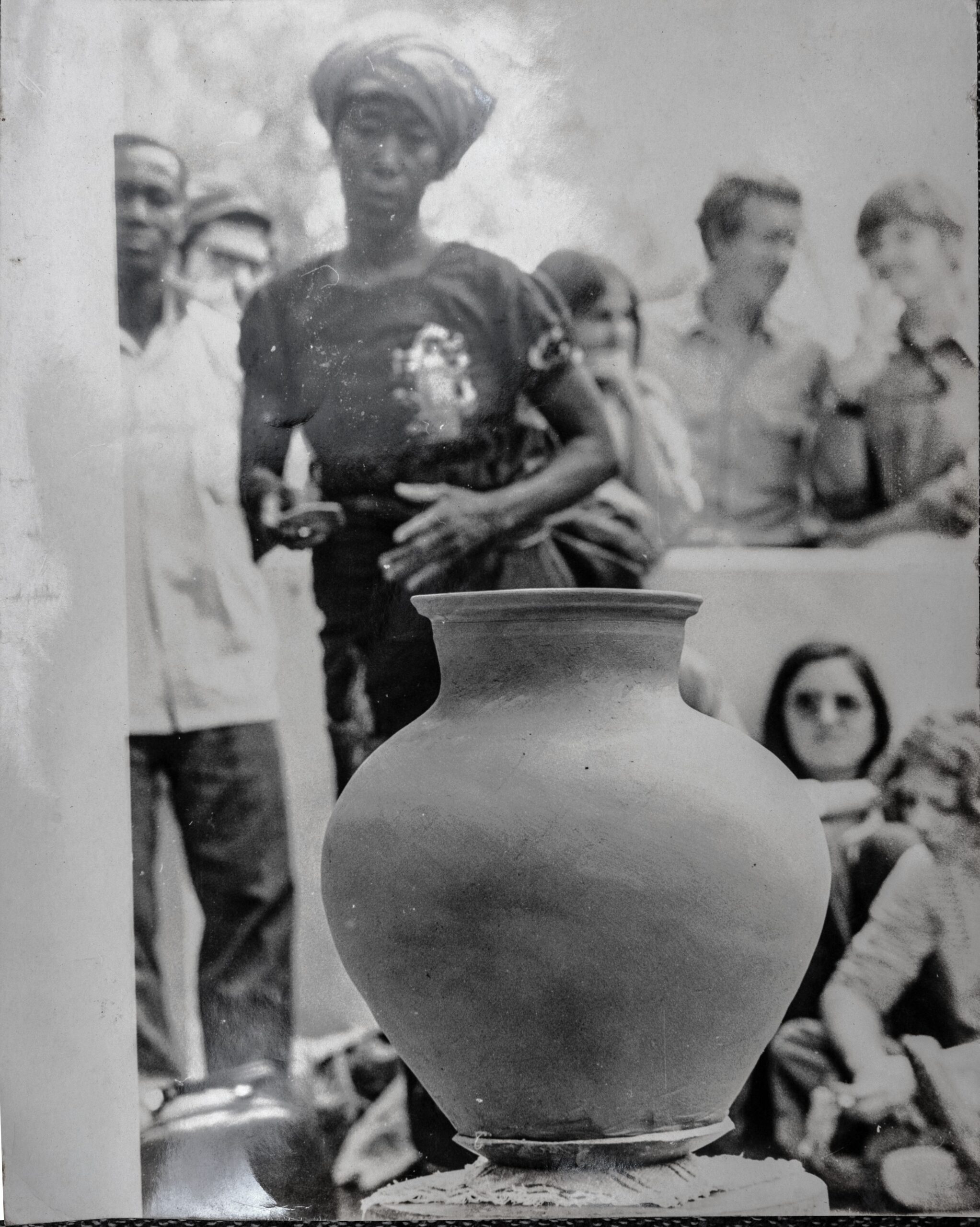

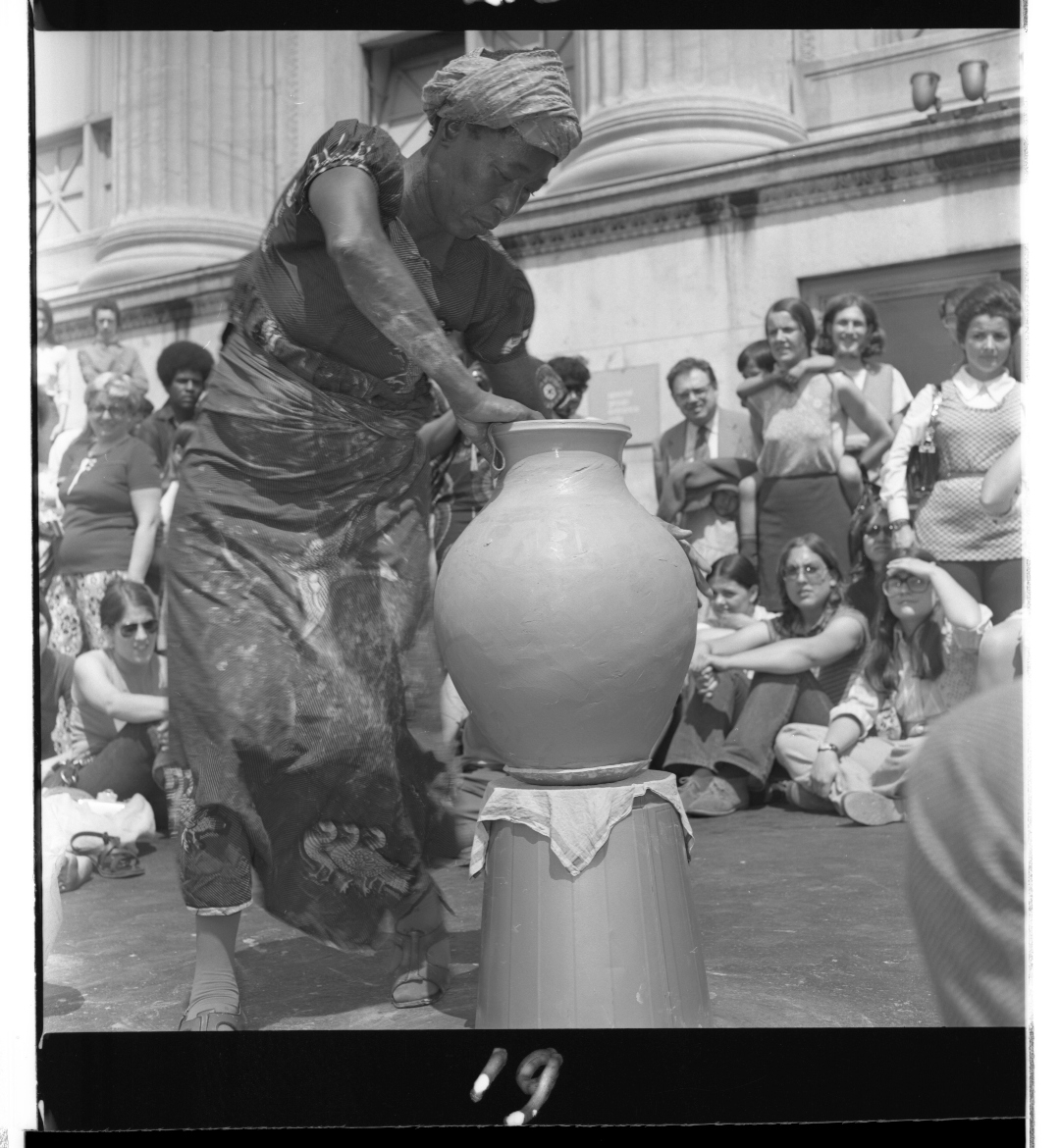

In a photograph of Ladi Kwali taken during a pottery demonstration in England in the 1970s by William Alfred Ismay (W. A. Ismay), the most active collector of British studio pottery at the time, Ladi Kwali is elegantly dressed in a pale blue polo shirt, brown patterned wrapper, earrings, and a brown silk head tie (fig. 2). Captured deep in concentration, she is shown incising a waterpot. Kwali was known for her fashion sense, a blend of traditional and Western styles of dress, mainly via the many demonstrations she carried out while touring Europe and the United States in 1962 and 1972, respectively.4In 1962, English studio potter Michael Cardew took Ladi Kwali to England on what would be her first international pottery demonstration tour. This was followed by a tour of Germany and Italy in 1963. In 1972, Kwali, Cardew, and Ghanaian potter Clement Kofi Athey traveled for two months across the United States, notably to the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), including Tennessee State University, Morgan State University, Morehouse College, and Spelman College, a tour sponsored by grants from the US government’s National Endowment for the Arts, National Council on Education and the Arts (NCECA), American Crafts Council, World Crafts Council, and Maryland State Arts Council.

For a detailed account of the Cardew-Kwali demonstrations in the United States, see Tanya Harrod, The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew; Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2012), 344–52. Kwali’s choice in clothing belies the physicality of her work, which required that she thrust her fist into a giant ball of clay and then, while circling it, stretch up what would become the wall of the pot with a scraper. She would go on to build the upper half with thick coils, paddle the whole vessel into shape, smooth and decorate it with roller patterns, and finally, incise it with Gbari figures of different creatures.

At the time of this photo, Kwali was in her late forties and had honed her craft in the Gbari tradition of hand-built pottery. Having demonstrated remarkable mastery, she had gained not only national acclaim but also international recognition for her work.5Ladi Kwali exhibited at Berkeley Galleries in London (1958, 1959, and 1962), and Galerie La Borne in Paris (1962). Her international recognition further grew, particularly in 1965, when she received a Silver Award of Excellence at the 10th International Exhibition of Ceramic Art, held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, for a jar adorned with traditional patterns. Kwali received many honors for pottery in her lifetime, including being made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in 1963 and earning an honorary doctorate degree from Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria, in 1977. In 1980, the Nigerian Government awarded her the insignia of the Nigerian National Order of Merit (NNOM), the highest national honor for academic achievement, and in 1981, she received the national honor of the Officer of the Order of the Niger (OON). Her precision and steady hand in using sharp blade-like tools to inscribe the clay resulted in the distinct lines visible on the vessel’s surface. In an interview, British Kenyan ceramist Magdalene A. N. Odundo (born 1950) reminisced about Kwali’s attention to detail, stating: “Oh boy, it was amazing. She would point out the mistakes I had made. It was her eye that had the ability to see, form, and correct it. She had a sense of geometry in her bones.” Odundo recounted that Ladi Kwali would “dance” around her pot as she raised and smoothed it, singing in pleasure at her success.6See Jennifer Higgie, host, Bow Down: A Podcast About Women in Art, podcast, season 2, episode 8, “Dame Magdalene Odundo on Ladi Kwali,” podcast, September 20, 2024, https://www.frieze.com/article/bow-down-dame-magdalene-odundo-ladi-kwali. Odundo had previously recalled meeting Kwali in 1974, when the younger potter began working at the Abuja Pottery Training Centre (now in Suleja). Odundo was introduced to Kwali by Michael Cardew (1901–1983), the center’s founder and a pioneer of the British studio pottery movement widely credited for reviving the slipware tradition in England, whom she had met while a student in Farnham that same year.7Higgie, “Dame Magdalene Odundo on Ladi Kwali.” This experience profoundly shaped her path and solidified her decision to pursue a career in pottery.

Ladi Kwali was heavily tattooed with symbols, and as Ismay’s photograph records, her name was prominently marked on her inner left arm, where the words “Akou Mista Dase, Ladi Kwali” are visible. In this iconic image, she firmly secures the pot by its rim with her left hand while making an incision down its wide belly with her right. Geometric horizontal bands are visible on the neck of the vessel. In his report titled Ladi Kwali: Nigeria’s Potter Extraordinary, which he prepared for the board of trustees of the Nigerian National Order of Merit, C. O. Adepegba proposes that Kwali’s tattoos are an extension of the decorative motifs that adorn Gbari pottery wares: “Since Ladi Kwali had tattoos of geometric figures on her body, it is easy to identify body markings among the Gbari as the only source of her geometric designs.”8C. O. Adepegba, Ladi Kwali: Nigeria’s Potter Extraordinary, report prepared for the board of trustees of the Nigerian National Merit Award, c. 1980. The report also cites observations made by historians Sarah Riddick and Clara Hieronymus that reference geometric-patterned tattoos, notably those on the backs of Gbari women and echoed in the designs on decorative pottery and, in varied form, on calabashes, wood carvings, and leatherwork in Kwali town and other parts of Nigeria. One could also speculate that Kwali’s tattoos and pottery designs reflect her deep engagement with folkloric and cultural symbolism and with the natural world and animals.

Kwali used the direct-pull method, which involves hand-building a waterpot directly from a lump of clay, to create pots like the one shown in Ismay’s photograph. This method enabled her to form a short, plump-bellied vessel with a narrow, flared-lip neck. To make taller vessels of different shapes, she used a makeshift rounded disk to create a small pot, which she then enlarged by adding clay coils. As she built up the body of the piece, she circled it clockwise and then counterclockwise, walking steadily backward while dragging one foot to maintain balance—a technique widely practiced by potters undertaking hand-building because it helps to prevent dizziness.

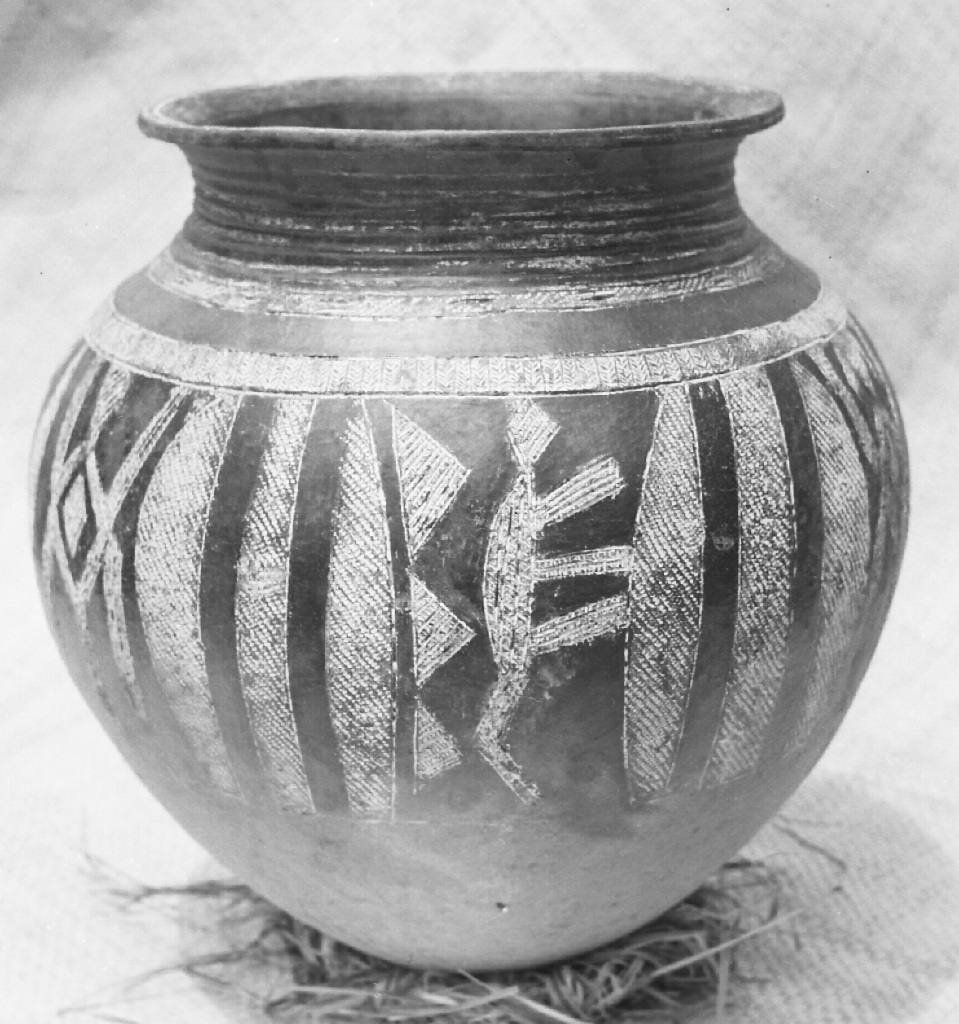

Ladi Kwali first encountered Michael Cardew in 1954, a few years after he arrived in Nigeria to take up his appointment as a senior potter officer employed by the Nigerian colonial government. Cardew researched Nigerian pottery traditions, touring the country and making extensive notes about methods, techniques, clay bodies, and mineral deposits for glazing. He chose a site in the Emirate of Abuja (now Suleja) for his Pottery Training Centre (PTC), a small-scale workshop intended to train boys and men to be potters by introducing them to modern techniques that would enable them to make wheel-thrown, glazed tableware (figs. 3, 4).

It is noteworthy that Cardew’s biographer, Tanya Harrod; scholar Lisa Bagley; and curator and scholar Susan Mullin Vogel have raised issues surrounding Cardew’s engagement in Nigeria. Bagley takes Cardew and his role to task, describing him as “at the intersection of Africa and the West in ceramics where he could act as a gatekeeper between African ceramists and Western audiences.”9See Kim Tracy Bagley, “Africa and the West: A Contested Dialogue in Modern and Contemporary Ceramics” (PhD thesis, University of Brighton, 2014), https://research.uca.ac.uk/2973/. Vogel and Harrod remark on the distinct separation and lack of engagement between Cardew and academic art movements in Nigeria, notably that of the Zaria Art Society, which was active in the 1950s and 1960s. Its members, known as the Zaria Rebels, promoted “natural synthesis,” a concept conceived of and advocated by the group’s founder, Uche Okeke.10For more on Cardew and the Abuja Pottery Training Centre, see Tanya Harrod, “Abuja: Creating a National Art, 1951–5,” in The Last Sane Man, 249–68. Natural synthesis called for merging the best of Western and Nigerian traditions. However, in Vogel’s view, many of the artists associated with the Zaria viewed Abuja pottery as old-fashioned and ethnographic.11For a detailed reading of Kwali’s mastery and public persona, see Susan Mullin Vogel, “Ladi Kwali, Michael Cardew and a Tangled Story of African Studio Pottery: Design Histories Between Africa and Europe,” in Flow of Forms / Forms of Flow, ed. Kerstin Pinther and Alexandra Weigand (transcript Verlag, 2018), 96–109. Harrod saw Cardew’s position as paradoxical—that of a modernist who disliked modernity and a colonial servant who despised the British Empire yet no doubt benefited from the privilege enabled by colonialism.12See Tanya Harrod, “‘a proper colonial servant’: Nigeria, 1950–1,” in The Last Sane Man, 236–45.

Cardew first saw Ladi Kwali’s pots on a customary visit to the palace of the emir of Abuja, Alhaji Suleiman Barau, who had several of her pots in his personal collection.13In a diary entry dated December 11, 1950, and titled “Minna to Abuja,” Michael Cardew reflects upon his research on red clay deposits particular to the town of Kwali, noting their properties and usefulness for local pottery. Underneath this is a drawing of a Gbari-Yamma pot (a Kwali-area pot that he describes as ocher in color with elaborately incised geometric and stylized zoomorphic details running from its rim and across its body. He then proclaims that the pot made by Ladi Kwali, is the “best I ever saw.”) Harrod, “‘a proper colonial servant’: Nigeria, 1950–1,” 244. Though Cardew’s initial plan was for a male-only pottery enterprise, he reconsidered this take after encountering Kwali’s pottery. With the encouragement of the emir, he accepted Ladi Kwali as a trainee and the center’s first female potter in 1954.

At the time of its establishment in the 1950s and mainly through to the 1970s, the PTC gained a reputation in England and internationally due to Cardew’s influence as an established British studio potter. He organized exhibitions at the Berkeley Galleries in London in 1958, 1959, and 1962, which proved pivotal to the recognition of Kwali’s internationalism as Cardew’s connection and the interest garnered from his Abuja pottery project led the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) to acquire one of her waterpots and some of her thrown wares. The waterpot, the first work by Kwali to be institutionally collected, is on permanent display in the Timothy Sainsbury Gallery, which houses part of the V&A’s ceramics collection.

Kwali’s success opened the door to other Gbari women potters, including Halima Audu, who joined the PTC in 1960 (but tragically died the following year). Asibi Ido joined in 1962, followed by Kande Ushafa and Lami Toto, both of whom arrived a year later, in 1963, and were active at the center until around the late 1970s. These women continued the legacy of Kwali and Gbari hand-building after Ladi Kwali’s passing in 1984. The potters were accustomed to pit-fired pottery, but Cardew introduced them to wheel-thrown, high-temperature, kiln-fired and glazed stoneware, which previously was assigned only to male trainees. As Susan Mullin Vogel has noted, “Kiln firing was an exclusively male occupation, while open bonfire was practiced mainly by women and universally used in African traditions where it had a meager failure rate.” While the techniques used by women “have been characterized as technically simple,” Vogel points out that this method requires a hyper-refined combination of a specific clay body, fuel, and firing technique as well as certain atmospheric conditions—a formula derived from local experimentation mainly by generations of women, in other words, through regional and Indigenous know-how.14For a detailed reading of Kwali’s mastery and public persona, see Vogel, “Ladi Kwali, Michael Cardew and a Tangled Story of African Studio Pottery,” 96–109.

Kwali created both hand-built vessels and thrown wares following Cardew’s method, but it was Cardew’s suggestion that she glaze her traditional Gbari-style waterpots with Chun or tenmoku high-temperature glazes (fig. 5), a finish never before used by Gbari potters.15Chun and tenmoku are types of ceramic glazes. Chun glazes are often pale blue or gray-blue, while tenmoku glazes are usually dark brown or tan. This hybridization transformed her pots from functional vessels to celebrated decorative art objects. As the scholar Emman Okunna observes: “This transition from tradition to modernity was a significant turning point in Ladi Kwali’s life and ceramic art practice. It marked an essential interface between the two domains in this iconic personality’s historical art experience. Ladi Kwali now saw herself in an entirely new domain, a testament to her adaptability and innovation.”16Okunna, “Living through two pottery traditions and the story of an icon,” 4–5. Even so—and though she was the PTC’s star potter—Kwali earned less than her male counterparts, as educational qualifications determined wages, and she had received no formal education. This discrepancy reflected the wage structure imposed on the center by the Nigerian colonial government, which determined and enforced salary bands.17In the W. A. Ismay archive, which is held by York Museums Trust and consists of Ismay’s collection of 3,600 pots by over 500 artists and a supporting archive of around 10,000 items, an Abuja pay slip details the different amounts paid out to trainees based on education and civil service salary bands imposed by the Nigerian colonial government.

Kwali’s adaptability, innovation, and agency, as Okunna observes, are evident in a portrait by Doig Simmons taken in 1959 (fig. 6). In Simmons’s black-and-white photograph, Ladi Kwali stands confidently in front of the main kiln, which can be seen at the center. She is dressed in a simple sleeveless sundress and her signature head tie. An unglazed terra-cotta waterpot sits at her feet, indicating that it is on its way to being glazed and then fired in the kiln behind her, a process that was, by then, her usual practice. We see a confident and aware maker standing proudly by her work, one of a series of waterpots adapted from Gbari pot-making tradition. Based on her working methods throughout her career, she clearly approached her “modern” stoneware ceramics not by sketching or inventing unique forms but rather through the creative processes she had learned in her village.

The portraits of Kwali discussed in this essay provide a lens for re-reading her agency as an astute, self-assured Gbari woman potter framed but not defined and contained by the colonial structure that brought about her international fame. As Marla C. Berns observes, although women are the primary producers of pottery in Africa, scholars have seldom attributed the creation of archaeologically recovered figurative ceramic sculptures to them. Moreover, the question of authorship regarding these esteemed ceramics has rarely been explored.18Marla C. Berns, “Art History and Gender: Women and Clay in West Africa,” in “Papers in Honor of Merrick Posnansky,” special issue, African Archaeological Review 11 (1993): 129–48. It is crucial to consider Kwali’s identity as rooted in place and context and in who she was before and after her interactions with Cardew and his Abuja pottery project. In addressing the methodological challenges of confronting object histories, one must consider Kwali’s Gbari identity and agency, which are imbued in the objects she left behind. Additionally, Kwali’s pottery embodies a pivotal moment of transformation and hybridity, merging Indigenous Nigerian ceramic traditions with British studio pottery and modern Western techniques.

In 2007, Kwali and her pots were immortalized on the reverse side of the Nigerian 20-naira bank note. This national tribute goes to show how important the artist is in Nigeria. Yet, just the same, historical accounts of her artistic journey remain scarce in comparison to her stature. Little public information exists about Kwali’s later years, and no known recorded or printed interviews document her experiences in Suleja and beyond. Her presence within Nigerian Modernism remains paradoxical—both absent and present—primarily overlooked by intellectuals of the period, who were no doubt aware of her. Still, it is peculiar that she is not cited as an influence given the overlapping period. Kwali’s works resonate with concepts of natural synthesis put forward by members of the Zaria Art Society, calling for the merging of the best of Western and Nigerian traditions, forms, techniques, and artistic ideas into a hybrid art-making practice and conceptual framework. Ceramist and scholar Professor Ozioma Onuzulike has argued for recognition of Kwali and other workshop-trained Indigenous female potters who used natural synthesis to achieve works that have contributed to the discourse on African modernism.19See Onuzulike, “‘Traditional’ Paradigm as Dividing Wall: Formal Analysis in the Study of African Ceramic Art Modernism,” Critical Interventions , no. 2–3 (2019): 158–79, https://doi.org/10.1080/19301944.2020.1855026. This marginalization was arguably shaped by Cardew’s deliberate detachment from the broader Nigerian artistic discourse and the fact that his pottery project upheld a colonial vision.

My recent trip to Kwali, the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), and Suleja in northern Nigeria to speak to Kwali’s surviving family members raised more questions than answers about how she is remembered. Only a few photographs of the artist and press clippings about her remain in her family archive (fig. 7). Public sculptures, street signs, and even a convention center named after her exist. However, aside from these visible civic and public markers, the most poignant reminders are the anecdotes. There are oral histories recounting stories of visitors from far and wide whom she welcomed into her home and of the critical support she provided to her family members during her lifetime. Additionally, Kwali’s descendants in Suleja hope that one day, her home will be transformed into a heritage site where visitors from around the world can once again come to learn about her(fig. 8). Kwali’s legacy—especially her waterpots—is rooted in everyday life. Easily recognizable as containers, carriers, and vessels that once simply held water, they nonetheless carry memories of an incredible potter whose work continues to transcend space and time. Ladi Dosei Kwali’s pots remain testaments to her personal story and its connection to town and country.

- 1Gbari people, also referred to as Gbayi/Gwari, are Indigenous to the states of Niger, Kaduna, Kogi, and Plateau and to the Federal Capital Territory.

- 2The papers of Michael Cardew, Crafts Study Centre Archives, University for the Creative Arts, GB 2941 MAC.

- 3E. Okunna, “Living through two pottery traditions and the story of an icon: Ladi Kwali,” Mgbakoigba: Journal of African Studies 1 (2012), https://www.ajol.info/index.php/mjas/article/view/117190.

- 4In 1962, English studio potter Michael Cardew took Ladi Kwali to England on what would be her first international pottery demonstration tour. This was followed by a tour of Germany and Italy in 1963. In 1972, Kwali, Cardew, and Ghanaian potter Clement Kofi Athey traveled for two months across the United States, notably to the Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), including Tennessee State University, Morgan State University, Morehouse College, and Spelman College, a tour sponsored by grants from the US government’s National Endowment for the Arts, National Council on Education and the Arts (NCECA), American Crafts Council, World Crafts Council, and Maryland State Arts Council.

For a detailed account of the Cardew-Kwali demonstrations in the United States, see Tanya Harrod, The Last Sane Man: Michael Cardew; Modern Pots, Colonialism and the Counterculture (Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art by Yale University Press, 2012), 344–52. - 5Ladi Kwali exhibited at Berkeley Galleries in London (1958, 1959, and 1962), and Galerie La Borne in Paris (1962). Her international recognition further grew, particularly in 1965, when she received a Silver Award of Excellence at the 10th International Exhibition of Ceramic Art, held at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, for a jar adorned with traditional patterns. Kwali received many honors for pottery in her lifetime, including being made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) in 1963 and earning an honorary doctorate degree from Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, Nigeria, in 1977. In 1980, the Nigerian Government awarded her the insignia of the Nigerian National Order of Merit (NNOM), the highest national honor for academic achievement, and in 1981, she received the national honor of the Officer of the Order of the Niger (OON).

- 6See Jennifer Higgie, host, Bow Down: A Podcast About Women in Art, podcast, season 2, episode 8, “Dame Magdalene Odundo on Ladi Kwali,” podcast, September 20, 2024, https://www.frieze.com/article/bow-down-dame-magdalene-odundo-ladi-kwali.

- 7Higgie, “Dame Magdalene Odundo on Ladi Kwali.”

- 8C. O. Adepegba, Ladi Kwali: Nigeria’s Potter Extraordinary, report prepared for the board of trustees of the Nigerian National Merit Award, c. 1980.

- 9See Kim Tracy Bagley, “Africa and the West: A Contested Dialogue in Modern and Contemporary Ceramics” (PhD thesis, University of Brighton, 2014), https://research.uca.ac.uk/2973/.

- 10For more on Cardew and the Abuja Pottery Training Centre, see Tanya Harrod, “Abuja: Creating a National Art, 1951–5,” in The Last Sane Man, 249–68.

- 11For a detailed reading of Kwali’s mastery and public persona, see Susan Mullin Vogel, “Ladi Kwali, Michael Cardew and a Tangled Story of African Studio Pottery: Design Histories Between Africa and Europe,” in Flow of Forms / Forms of Flow, ed. Kerstin Pinther and Alexandra Weigand (transcript Verlag, 2018), 96–109.

- 12See Tanya Harrod, “‘a proper colonial servant’: Nigeria, 1950–1,” in The Last Sane Man, 236–45.

- 13In a diary entry dated December 11, 1950, and titled “Minna to Abuja,” Michael Cardew reflects upon his research on red clay deposits particular to the town of Kwali, noting their properties and usefulness for local pottery. Underneath this is a drawing of a Gbari-Yamma pot (a Kwali-area pot that he describes as ocher in color with elaborately incised geometric and stylized zoomorphic details running from its rim and across its body. He then proclaims that the pot made by Ladi Kwali, is the “best I ever saw.”) Harrod, “‘a proper colonial servant’: Nigeria, 1950–1,” 244.

- 14For a detailed reading of Kwali’s mastery and public persona, see Vogel, “Ladi Kwali, Michael Cardew and a Tangled Story of African Studio Pottery,” 96–109.

- 15Chun and tenmoku are types of ceramic glazes. Chun glazes are often pale blue or gray-blue, while tenmoku glazes are usually dark brown or tan.

- 16Okunna, “Living through two pottery traditions and the story of an icon,” 4–5.

- 17In the W. A. Ismay archive, which is held by York Museums Trust and consists of Ismay’s collection of 3,600 pots by over 500 artists and a supporting archive of around 10,000 items, an Abuja pay slip details the different amounts paid out to trainees based on education and civil service salary bands imposed by the Nigerian colonial government.

- 18Marla C. Berns, “Art History and Gender: Women and Clay in West Africa,” in “Papers in Honor of Merrick Posnansky,” special issue, African Archaeological Review 11 (1993): 129–48.

- 19See Onuzulike, “‘Traditional’ Paradigm as Dividing Wall: Formal Analysis in the Study of African Ceramic Art Modernism,” Critical Interventions , no. 2–3 (2019): 158–79, https://doi.org/10.1080/19301944.2020.1855026.